Do Peer Cliques and Gender Differences Shape Adolescent Depression Under Bullying? Exploring the Mediating Power of Cognitive Biases

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Depression and Victimization

1.2. The Effects of Cognitive Biases: Beck’s Model

1.3. The Moderating Role of Clique Victimization Norms and Unresolved Theoretical Questions

1.4. Potential Gender Differences

1.5. Current Study and Depression in Chinese Culture

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cognitive Biases

2.2.2. Peer Victimization

2.2.3. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.4. Peer Cliques

2.2.5. Clique Victimization Norms

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. The Unconditional Model

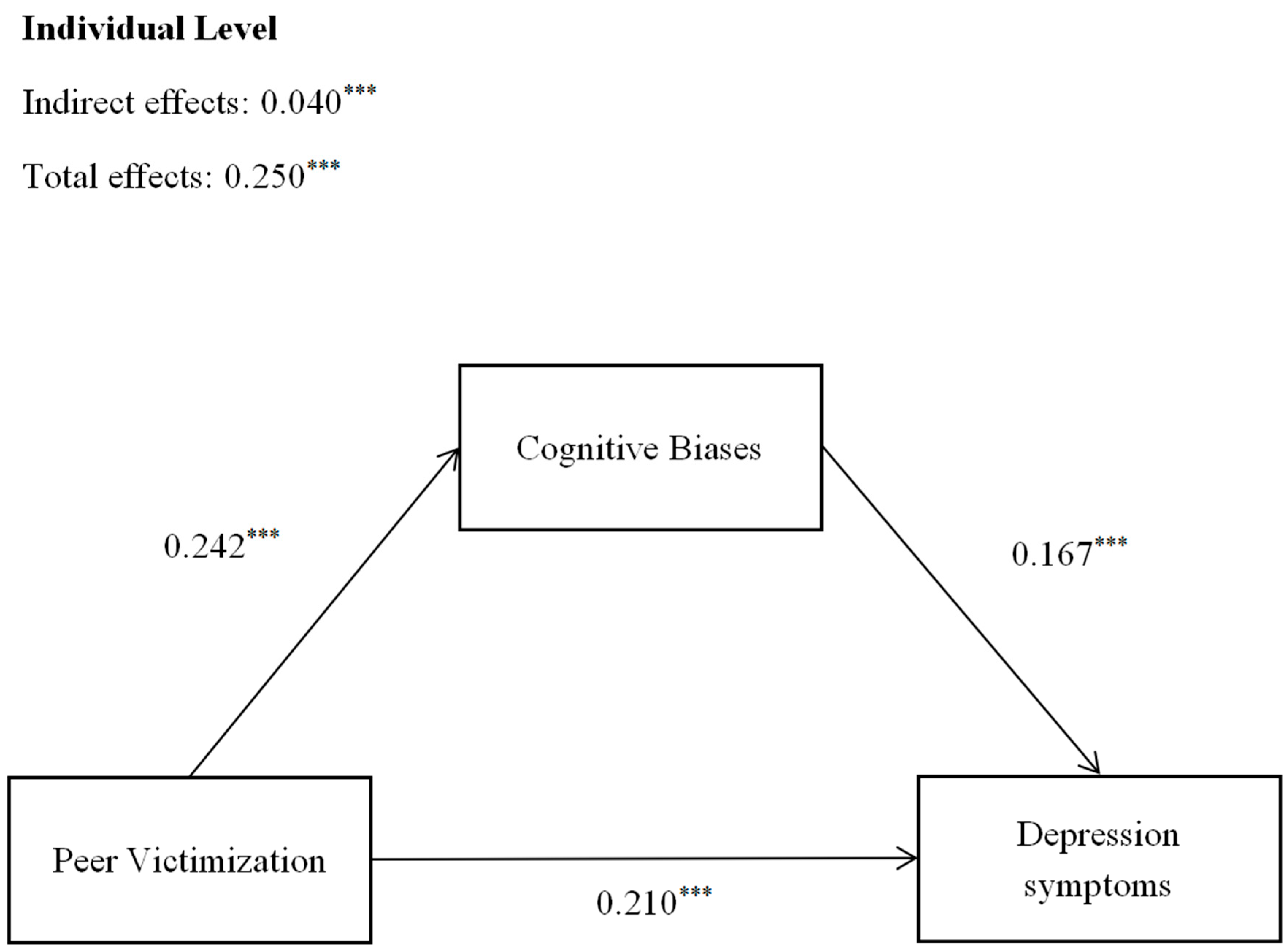

3.3. The Individual-Level Mediating Model

3.4. The Clique-Level Model

3.5. Supplementary Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effects of Cognitive Biases

4.2. The Interaction Effects of Individual and Clique Victimization

4.3. Gender Differences

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

4.5. Strengths and Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akıncı, Z., & Güven, M. (2015). A study on investigation of the relationship between mobbing and depression according to genders of high school students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M. W. (1992). Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin, 112(3), 461–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal, Y., & Jarymowicz, M. (2010). The effect of gender on cognitive structuring: Who are more biased, men or women? Psychology, 1(2), 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T. (2008). The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(8), 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthet, V. (2021). The measurement of individual differences in cognitive biases: A review and improvement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 630177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomyea, J., Johnson, A., & Lang, A. J. (2017). Information processing in PTSD: Evidence for biased attentional, interpretation, and memory processes. Psychopathology Review, 4(3), 218–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R. B., Cairns, B. D., Neckerman, H. J., Gest, S. D., & Gariepy, J.-L. (1988). Social networks and aggressive behavior: Peer support or peer rejection? Developmental Psychology, 24(6), 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Fernández-González, L., González-Cabrera, J. M., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2018). Continued bullying victimization in adolescents: Maladaptive schemas as a mediational mechanism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(3), 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., & Chen, X. (2020). Affiliation with depressive peer groups and social and school adjustment in Chinese adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 32(3), 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84, 19–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D. A., Dukewich, T. L., Roeder, K., Sinclair, K. R., McMillan, J., Will, E., Bilsky, S. A., Martin, N. C., & Felton, J. W. (2014). Linking peer victimization to the development of depressive self-schemas in children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(1), 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A., Zelkowitz, R. L., Nick, E., Martin, N. C., Roeder, K. M., Sinclair-McBride, K., & Spinelli, T. (2016). Longitudinal and incremental relation of cyber victimization to negative self-cognitions and depressive symptoms in young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(7), 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranowski, J. M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, M. K. (2000). Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dishion, T. J., Spracklen, K. M., Andrews, D. W., & Patterson, G. R. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K. A., Dishion, T. J., & Lansford, J. E. (2006). Deviant peer influences in intervention and public policy for youth. Social Policy Report, 20, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 2, 458–476. [Google Scholar]

- Everaert, J., Koster, E. H., & Derakshan, N. (2012). The combined cognitive bias hypothesis in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(5), 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W., Luo, Y., Cao, X., & Liu, X. (2022). Gender differences in the relationship between self-esteem and depression among college students: A cross-lagged study from China. Journal of Research in Personality, 97, 104202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, C. F., Lee, I. A., & Salmivalli, C. (2018). Decreases in the proportion of bullying victims in the classroom: Effects on the adjustment of remaining victims. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(1), 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garandeau, C. F., & Salmivalli, C. (2019). Can healthier contexts be harmful? A new perspective on the plight of victims of bullying. Child Development Perspectives, 13(3), 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, D. E., & Shaw, B. F. (1987). Beck’s cognitive theory of depression: Convergence of constructs. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28(5), 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgus, J. S., & Yang, K. (2015). Gender and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(4), 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T. Q., Zhang, D. J., & Yang, Z. Z. (2015). The Relationship Between Attributional Style for Negative Outcomes and Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(4), 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitsing, G., Lodder, G. M. A., Oldenburg, B., Schacter, H. L., Salmivalli, C., Juvonen, J., & Veenstra, R. (2019). The healthy context paradox: Victims’ adjustment during an anti-bullying intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(9), 2499–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellij, S., Lodder, G., van den Bedem, N., Güroğlu, B., & Veenstra, R. (2022). The social cognitions of victims of bullying: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 7(3), 287–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Avenevoli, S., & Merikangas, K. R. (2001). Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klomek, A. B., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2008). Peer victimization, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(2), 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehner, C. (2017). Why is depression more common among women than among men? The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitenberg, H., Yost, L. W., & Carroll-Wilson, M. (1986). Negative cognitive errors in children: Questionnaire development, normative data, and comparisons between children with and without self-reported symptoms of depression, low self-esteem, and evaluation anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. J., Kremer, P., Douglas, K., Toumborou, J. W., Hameed, M. A., Patton, G. C., & Williams, J. (2015). Gender differences in adolescent depression: Differential female susceptibility to stressors affecting family functioning. Australian Journal of Psychology, 67, e131–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Fraser, M. W., & Wike, T. L. (2013). Promoting social competence and preventing childhood aggression: A framework for applying social information processing theory in intervention research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(3), 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. The American Psychologist, 70(4), 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, I., Robles, E., & Vazquez, C. (2020). Self-reported cognitive biases in depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B., Li, T., Ji, L., Malamut, S., Zhang, W., & Salmivalli, C. (2021). Why does classroom-level victimization moderate the association between victimization and depressive symptoms? The “Healthy Context Paradox” and two explanations. Child Development, 92(5), 1836–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinelli, M., & Wilkinson, G. (2000). Gender differences in depression: Critical review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, P. J., Milich, R., & Harris, M. J. (2007). Victims of their own cognitions: Implicit social cognitions, emotional distress, and peer victimization. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 28(3), 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, S., & Mouzon, D. (2013). Gender and mental health. In Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 277–296). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, H. L., & Juvonen, J. (2015). The effects of school-level victimization on self-blame: Evidence for contextualized social cognitions. Developmental Psychology, 51(6), 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selig, J. P., Card, N. A., & Little, T. D. (2008). Latent variable structural equation modelling in cross-cultural research: Multigroup and multilevel approaches. In F. J. R. van de Vijver, D. A. van Hemert, & Y. H. Poortinga (Eds.), Multilevel analysis of individuals and cultures (pp. 93–119). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S., Guo, R., Chen, X., & Li, C. (2025). How school burnout affects depression symptoms among Chinese adolescents: Evidence from individual and peer clique level. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 54(1), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (2004). Introduction: A social–ecological framework of bullying among youth. In D. L. Espelage, & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention (pp. 1–12). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting, H., Young, R., West, P., & Der, G. (2006). Peer victimization and depression in early–mid adolescence: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, M., Goemans, A., Zwaanswijk, W., Gini, G., & Vedder, P. (2018). Does peer victimization predict low self-esteem, or does low self-esteem predict peer victimization? Meta-analyses on longitudinal studies. Developmental Review, 49, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, D., & Lereya, S. T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(9), 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. X., & Wu, J. F. (1999). Revision of the Chinese Version of the Olweus Bullying Questionnaire. Psychological Development and Education, 15(2), 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q., & Li, C. (2022). The Roles of Clique Status Hierarchy and Aggression Norms in Victimized Adolescents’ Aggressive Behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51, 2328–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||||||||||

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| boys | ||||||||||

| 1 Age | 13.28 | 0.68 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Peer Victimization | 0.48 | 0.75 | −0.03 | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Cognitive Biases | 2.33 | 0.66 | 0.01 | 0.27 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4 Depressive Symptoms | 1.81 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.37 ** | 0.28 ** | 1 | ||||

| girls | ||||||||||

| 1 Age | 13.24 | 0.65 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Peer Victimization | 0.34 | 0.56 | −0.45 | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Cognitive Biases | 2.42 | 0.63 | 0.11 ** | 0.20 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4 Depressive Symptoms | 1.86 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.38 ** | 0.34 ** | 1 | ||||

| (b) | ||||||||||

| t | df | p | 99%CI | Cohen’s d | ||||||

| LB | UB | |||||||||

| Age | 2.159 | 2526.982 | 0.300 | −0.011 | 0.126 | 0.672 | ||||

| peer-victimization | −2.705 | 2256.834 | 0.007 | −0.096 | −0.002 | 0.434 | ||||

| cognitive biases | 5.115 | 2179.764 | <0.001 | 0.071 | 0.215 | 0.672 | ||||

| depressive symptoms | −3.032 | 2223.010 | 0.002 | −0.154 | −0.012 | 0.652 | ||||

| (c) | ||||||||||

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| 1 Clique Proportion of Boys | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Clique Size | 4.64 | 1.64 | 0.12 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Clique Victimization Norms | 1.60 | 1.19 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | |||||

| Cognitive Biases | Depressive Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95% CI | B | 95% CI | |

| Peer Victimization | 0.242 *** | [0.199, 0.288] | 0.210 *** | [0.171, 0.249] |

| Cognitive Biases | - | - | 0.167 *** | [0.139, 0.195] |

| Mediation effect | - | - | 0.040 *** | [0.031, 0.052] |

| The Clique-Level Model | ||

| Cognitive Biases | Depressive Symptoms | |

| B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| Individual Level | ||

| Intercept | 2.380 (0.017) *** | 1.835 (0.011) *** |

| Gender | −0.126 (0.128) | −0.145 (0.073) * |

| Age | 0.036 (0.043) | −0.007 (0.025) |

| Peer Victimization | 0.273 (0.033) *** | 0.205 (0.024) *** |

| Cognitive Biases | - | 0.148 (0.018) *** |

| Clique Level | ||

| Clique Boy Proportion | −0.075 (0.035) * | −0.040 (0.023) † |

| Clique Size | −0.003 (0.009) | −0.003 (0.006) |

| Clique Victimization Norms | 0.038 (0.014) ** | 0.006 (0.009) |

| Cross-Level Interaction | ||

| Victimization × Clique Boy Proportion | −0.005 (0.067) | 0.002 (0.021) |

| Victimization × Clique Size | 0.005 (0.016) | −0.011 (0.012) |

| Victimization × Clique Victimization Norms | −0.056 (0.031) † | 0.002 (0.021) |

| Random Effect | ||

| Residual (σ2) | 0.371 (0.015) *** | 0.133 (0.005) *** |

| Intercept (τ00) | 0.017 (0.008) * | 0.017 (0.004) *** |

| Slope (τ01) | 0.013 (0.015) | 0.033 (0.008) *** |

| Model | |

|---|---|

| B (SE) | |

| Low Victimization Norms | 0.340 (0.049) *** |

| High Victimization Norms | 0.208 (0.049) *** |

| Difference between the two conditional effects | 0.132 (0.074) † |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Li, C.; Wang, T. Do Peer Cliques and Gender Differences Shape Adolescent Depression Under Bullying? Exploring the Mediating Power of Cognitive Biases. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010068

Wang X, Li C, Wang T. Do Peer Cliques and Gender Differences Shape Adolescent Depression Under Bullying? Exploring the Mediating Power of Cognitive Biases. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xingyuan, Caina Li, and Tianyang Wang. 2026. "Do Peer Cliques and Gender Differences Shape Adolescent Depression Under Bullying? Exploring the Mediating Power of Cognitive Biases" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010068

APA StyleWang, X., Li, C., & Wang, T. (2026). Do Peer Cliques and Gender Differences Shape Adolescent Depression Under Bullying? Exploring the Mediating Power of Cognitive Biases. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010068