Understanding Motivation in Early Childhood: Disentangling the Links Among Curiosity, Mindset, and Goals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Curiosity

2.3.2. Growth Mindset

2.3.3. Achievement Goals

3. Results

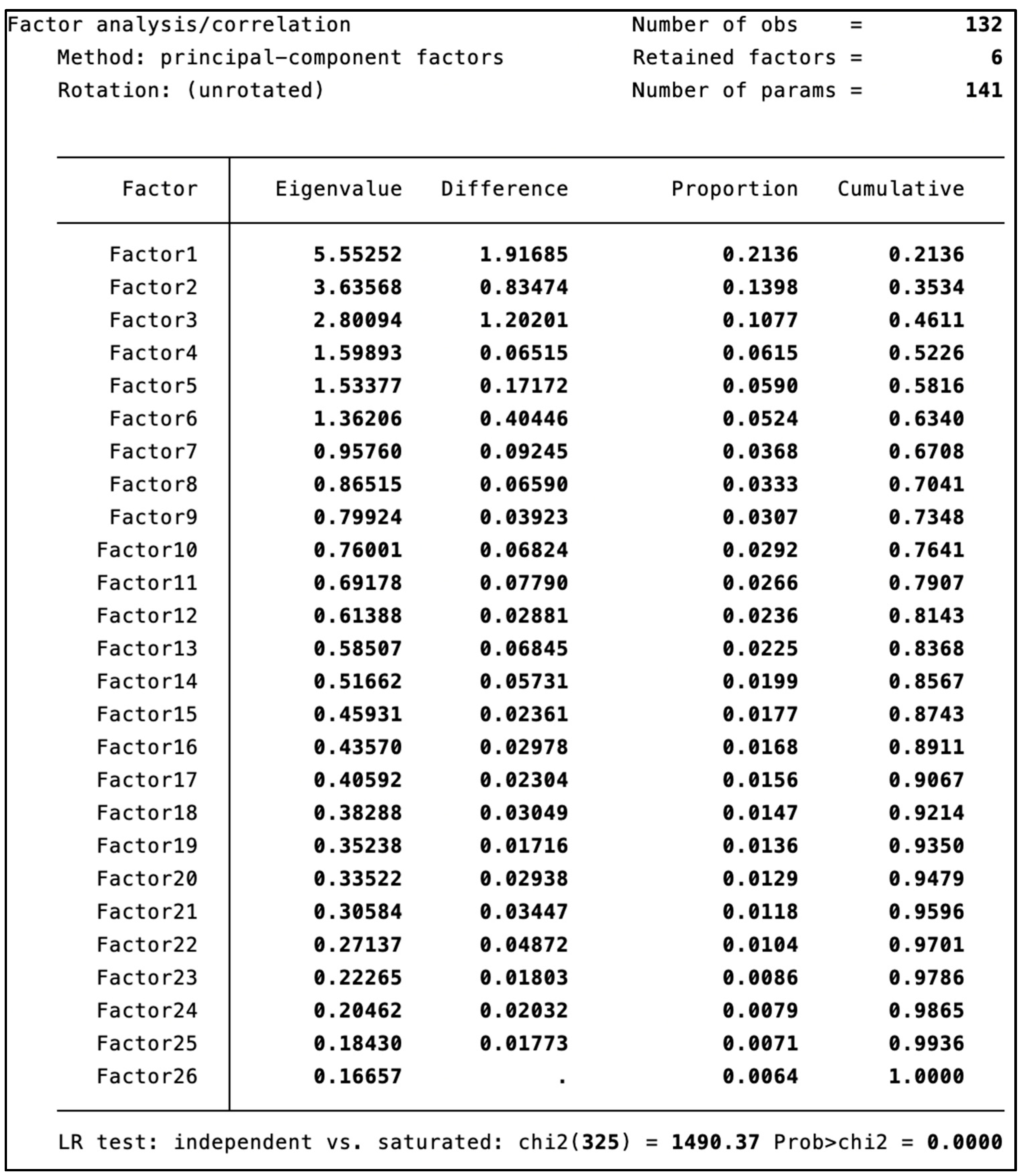

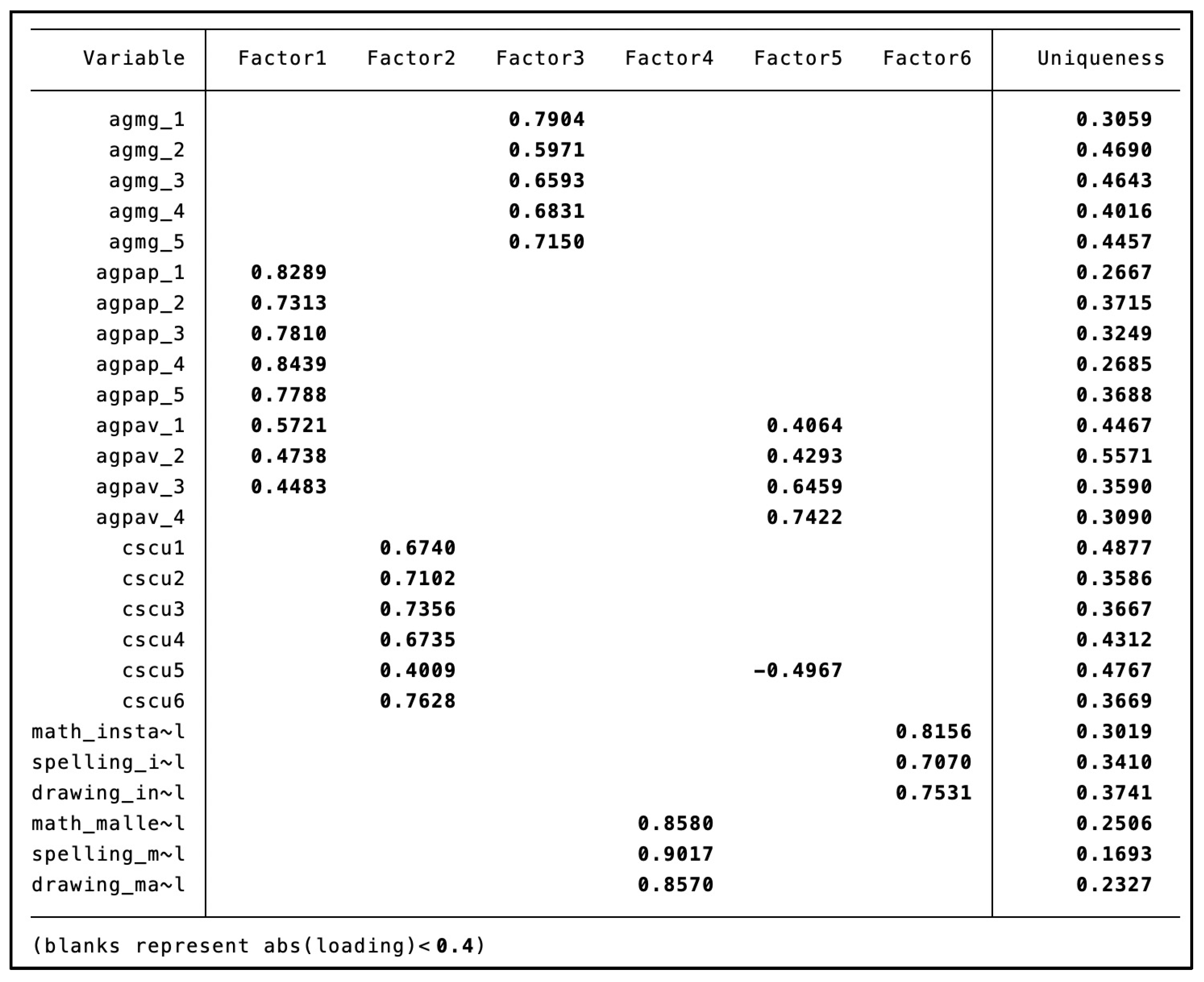

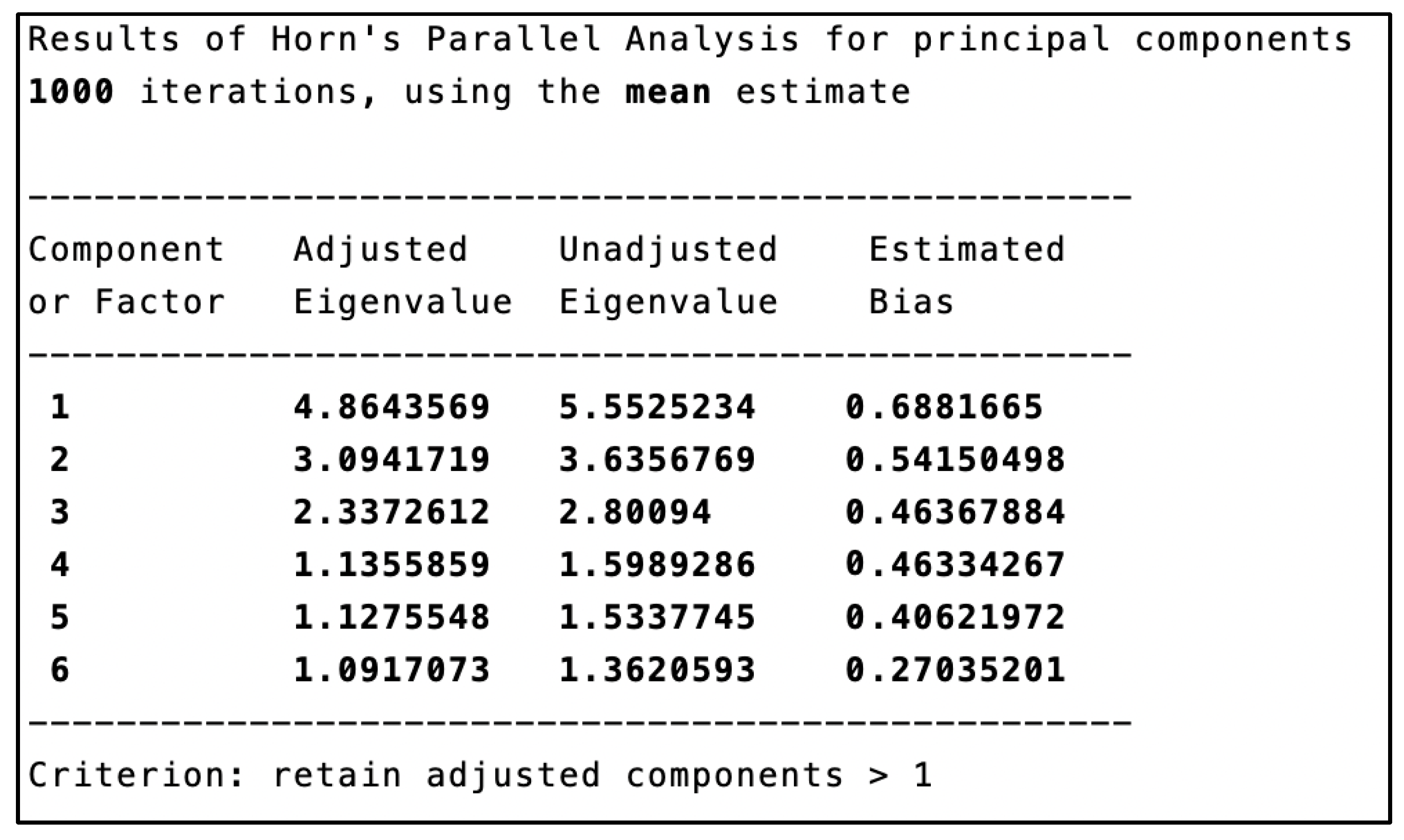

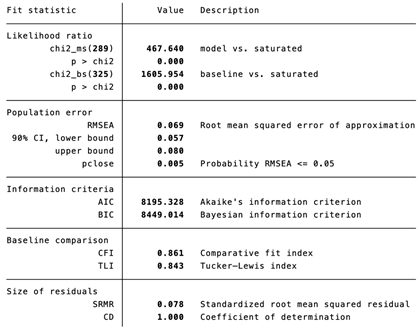

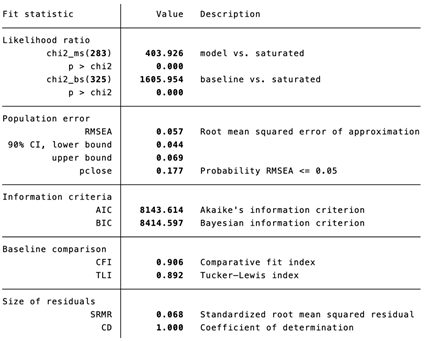

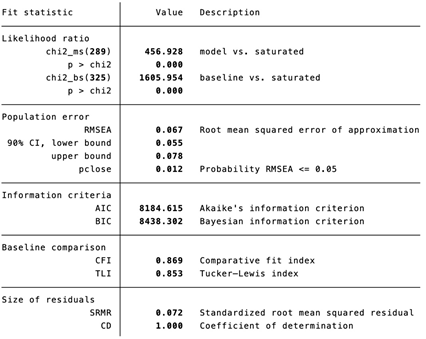

3.1. RQ1: Can Curiosity, Growth Mindset, and Achievement Goals Be Measured as Distinct Constructs?

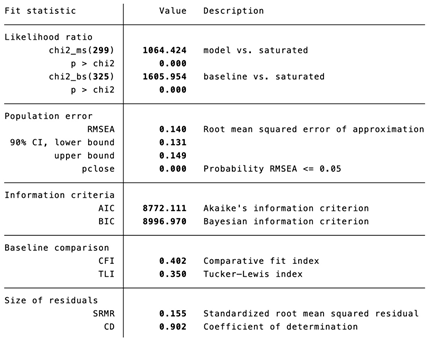

3.2. RQ2: How Do Children’s Curiosity, Growth Mindset, and Achievement Goal Orientation Relate?

3.3. RQ3: How Does Age Relate to Children’s Curiosity, Growth Mindset, and Achievement Goal Orientation?

3.4. Exploratory RQ: Controlling for Age, Is Curiosity Predicted Separately by Both Growth Mindset and Mastery Achievement Goals?

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

| Model | Goodness of Fit Indices |

|---|---|

| Uni-Factor: One singular construct |  |

| Five-Factor Growth Mindset Combined: Curiosity, Growth Mindset, Mastery Goal Orientation, Performance Approach Orientation, and Performance Avoidance Orientation |  |

| Six-Factor: Curiosity, Growth Mindset—malleability of ability, Growth Mindset—instability of ability, Mastery Goal Orientation, Performance Approach Orientation, and Performance Avoidance Orientation |  |

| Five-Factor Performance Combined: Curiosity, Growth Mindset—malleability of ability, Growth Mindset—instability of ability, Mastery Goal Orientation, Performance Orientation |  |

References

- Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, E. M., Austin, C. C., & Johnson, D. M. (2002). The development of goal orientation. In Development of achievement motivation (pp. 197–220). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderman, E. M., & Midgley, C. (1997). Changes in achievement goal orientations, perceived academic competence, and grades across the transition to middle-level schools. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22(3), 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderman, L. H., & Anderman, E. M. (1999). Social predictors of changes in students’ achievement goal orientations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, K. E., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2001). Achievement goals and optimal motivation: Testing multiple goal models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(5), 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bong, M. (2001). Between-and within-domain relations of academic motivation among middle and high school students: Self-efficacy, task value, and achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon-Falleur, M., Bouguen, A., Charpentier, A., Algan, Y., Huillery, É., & Chevallier, C. (2022). Simple questionnaires outperform behavioral tasks to measure socio-emotional skills in students. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, J. L., O’boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. (1987). Task-involving and ego-involving properties of evaluation: Effects of different feedback conditions on motivational perceptions, interest, and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. A., & Bowles, R. P. (2018). Model fit and item factor analysis: Overfactoring, underfactoring, and a program to guide interpretation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(4), 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 113(31), 8664–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, C. I., & Dweck, C. S. (1980). An analysis of learned helplessness: II. The processing of success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Caution-praise can be dangerous. American Educator, 23, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, S. (2011). Children’s need to know: Curiosity in schools. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhard, G., & Monsaas, J. A. (1988). Grade level, gender, and school-related curiosity in urban elementary schools. The Journal of Educational Research, 82(1), 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N. S., Burke, R., Vitiello, V., Zumbrunn, S., & Jirout, J. J. (2023). Curiosity in classrooms: An examination of curiosity promotion and suppression in preschool math and science classrooms. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 49, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N. S., & Jirout, J. J. (2023). Investigating the relation between curiosity and creativity. Journal of Creativity, 33(1), 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X., & Sivo, S. A. (2007). Sensitivity of fit indices to model misspecification and model types. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(3), 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, J. W., & Elliot, A. J. (2007). Stability and change in achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboy, M. B., Heinerichs, S., & Pazzaglia, G. (2015). Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47(1), 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, A. E., Preston, K. S. J., Gottfried, A. W., Oliver, P. H., Delany, D. E., & Ibrahim, S. M. (2016). Pathways from parental stimulation of children’s curiosity to high school science course accomplishments and science career interest and skill. International Journal of Science Education, 38(12), 1972–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajcevci, A., & Shala, A. (2021). Exploring achievement goals tendencies in students: The link between achievement goals and types of motivation. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 12(1), 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Pintrich, P. R., Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Revision of achievement goal theory: Necessary and illuminating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, G. D., & Giles, J. W. (2004). Valence effects in reasoning about evaluative traits. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(1), 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. C., Hwang, M. Y., Tai, K. H., Kuo, Y. C., & Lin, P. C. (2017). Confusion affects gameplay. Learning and Individual Differences, 59, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirout, J., & Klahr, D. (2012). Children’s scientific curiosity: In search of an operational definition of an elusive concept. Developmental Review, 32(2), 125–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirout, J. J. (2020). Supporting early scientific thinking through curiosity. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirout, J. J., Vitiello, V. E., & Zumbrunn, S. K. (2018). Curiosity in schools. The New Science of Curiosity, 1(1), 243–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A., & Maehr, M. L. (2007). The contributions and prospects of goal orientation theory. Educational Psychology Review, 19(2), 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinlaw, C. R., & Kurtz-Costes, B. (2007). Children’s theories of intelligence: Beliefs, goals, and motivation in the elementary years. The Journal of General Psychology, 134(3), 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpolovie, P. J., Joe, A. I., & Okoto, T. (2014). Academic achievement prediction: Role of interest in learning and attitude towards school. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE), 1(11), 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Limon, M. (2006). The domain generality–specificity of epistemological beliefs: A theoretical problem, a methodological problem or both? International Journal of Educational Research, 45(1–2), 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquin, E. G., & Gopnik, A. (2022). Children are more exploratory and learn more than adults in an approach-avoid task. Cognition, 218, 104940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, J. A. (2008). Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, J. L., & Miller, S. D. (2001). A longitudinal analysis of elementary school students’ achievement goals in literacy activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26(4), 454–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, M. J., Kaplan, A., & Midgley, C. (2004). The change in middle school students’ achievement goals in mathematics over time. Social Psychology of Education, 7(3), 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L. Z., Anderman, E., Anderman, L., Freeman, K. E., & Urdan, T. (2000). Manual for the patterns of adaptive learning scales (pp. 734–763). University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Miele, D. B., & Molden, D. C. (2010). Naive theories of intelligence and the role of processing fluency in perceived comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(3), 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millham, J., & Jacobson, L. I. (1978). The need for approval. In H. London, & J. E. Exner (Eds.), Dimensions of personality (pp. 365–390). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, A. K., & Edwards, M. C. (2021). The poor fit of model fit for selecting number of factors in exploratory factor analysis for scale evaluation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 81(3), 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradoglu, M., Lassetter, B., Sewell, M. N., Ontai, L., Napolitano, C. M., Dweck, C., Trzesniewski, K., & Cimpian, A. (2025). The structure and motivational significance of early beliefs about ability. Developmental Psychology. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradoglu, M., Porter, T., Trzesniewski, K., & Cimpian, A. (2024). A growth mindset scale for young children (GM-C): Development and validation among children from the United States and South Africa. PLoS ONE, 19(10), e0311205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, B. (2018). The neuroscience of growth mindset and intrinsic motivation. Brain Sciences, 8(2), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. D., Cannata, M., & Miller, J. (2018). Understanding student behavioral engagement: Importance of student interaction with peers and teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(2), 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: From achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E. G., & Cohen, J. (2019). A case for domain-specific curiosity in mathematics. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 807–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Saxon, J. L. (2001). Conceptions of ability as stable and self-evaluative processes: A longitudinal examination. Child Development, 72(1), 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, T., & van der Molen, J. H. W. (2018). Do children express curiosity at school? Exploring children’s experiences of curiosity inside and outside the school context. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 18, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, T., & van der Molen, J. H. W. (2021). Effects of an inquiry-focused school improvement program on the development of pupils’ attitudes towards curiosity, their implicit ability and effort beliefs, and goal orientations. Motivation and Emotion, 45(1), 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruble, D. N., Boggiano, A. K., Feldman, N. S., & Loebl, J. H. (1980). Developmental analysis of the role of social comparison in self-evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 16(2), 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, V., & Preckel, F. (2019). Development of motivational variables and self-esteem during the school career: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Review of Educational Research, 89(2), 211–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P. E., Weeks, H. M., Richards, B., & Kaciroti, N. (2018). Early childhood curiosity and kindergarten reading and math academic achievement. Pediatric Research, 84(3), 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sik, K., Cummins, J., & Job, V. (2024). An implicit measure of growth mindset uniquely predicts post-failure learning behavior. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiley, P. A., & Dweck, C. S. (1994). Individual differences in achievement goals among young children. Child Development, 65(6), 1723–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipek, D., & Gralinski, J. H. (1996). Children’s beliefs about intelligence and school performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J. E. (1999). The effects of theories of intelligence on the meanings that children attach to achievement goals. New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Tizard, B., & Hughes, M. (1984). Young children learning. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vogl, E., Pekrun, R., & Loderer, K. (2021). Epistemic emotions and metacognitive feelings. In Trends and prospects in metacognition research across the life span: A tribute to Anastasia Efklides (pp. 41–58). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2009). The motivational landscape of early adolescence in the United States and China: A longitudinal investigation. Child Development, 80(4), 1272–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2020). 35 years of research on students’ subjective task values and motivation: A look back and a look forward. In Advances in motivation science (Vol. 7, pp. 161–198). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis-Kean, P. (2007). Development of achievement motivation. In Handbook of child psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Tipton, E., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., Paunesku, D., Romero, C., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Iachan, R., Buontempo, J., Yang, S. M., Carvalho, C. M., … Dweck, C. S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J., & McLellan, R. (2020). Same mindset, different goals and motivational frameworks: Profiles of mindset-based meaning systems. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 62, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

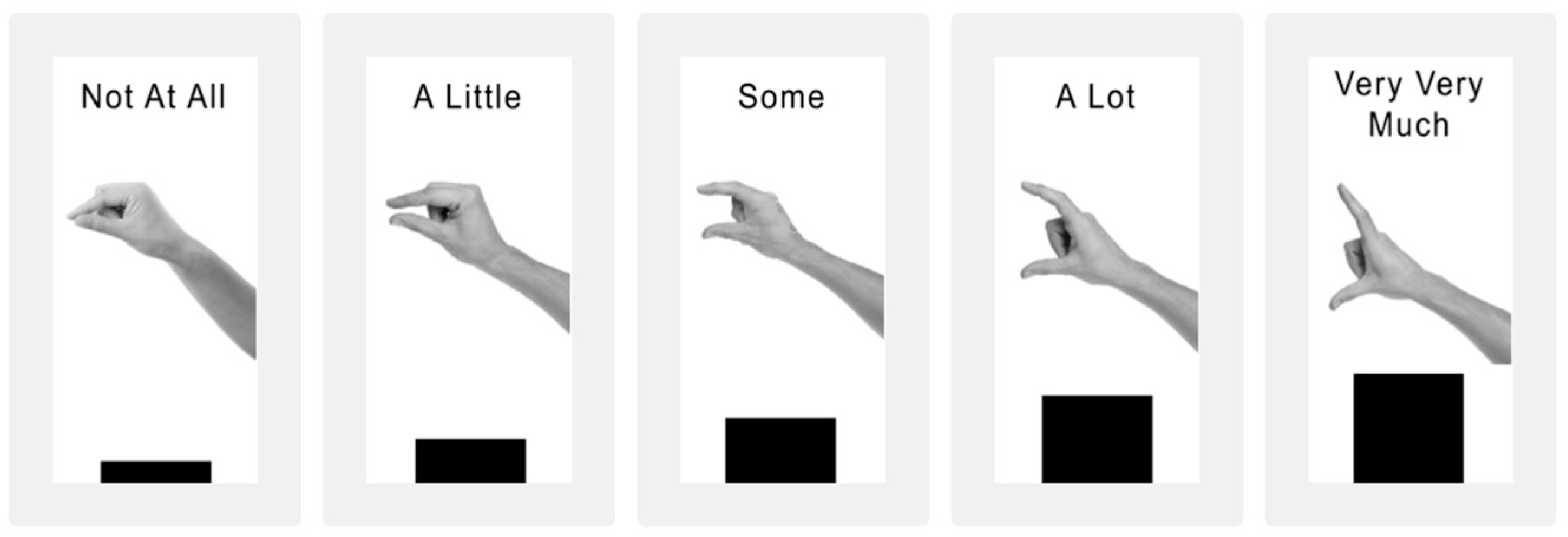

| Curiosity (Evans & Jirout, 2023) |

| How much is this like you? Not at all (1), A Little (2), Some (3), A Lot (4), Very Very Much (5) |

|

| Growth Mindset (Muradoglu et al., 2024) Modified to include two characters, one of each gender, to mitigate gender biases across domains. Example scale items for math subject. Other subjects include spelling & drawing. |

| Instability of Ability |

This is Jamie and Riley. And here’s something about Jamie and Riley: Jamie and Riley aren’t very good at math. Jamie and Riley get a lot of math problems wrong on their schoolwork. I just want to make sure you were paying attention: Are Jamie and Riley good at math? Or not good at math? [corrective feedback provided]

|

| Malleability of Ability |

Now let me tell you what happened with Jamie and Riley. When Jamie and Riley were a little older, they moved to a school far away. At this school, kids do a lot of math. After Jamie and Riley started at this far-away school, they got to practice math a lot. Jamie and Riley did a lot of math at this school.

|

| Achievement Goal Orientation (age adapted Midgley et al., 2000) |

| How much is this like you? Not at all (1), A Little (2), Some (3), A Lot (4), Very Very Much (5) |

| Mastery Goal Orientation |

|

| Performance Approach |

|

| Performance Avoidance |

|

| Variables | N | M | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Age | 212 | 8.31 | ||||||

| (2) Curiosity | 210 | 3.63 | −0.005 | |||||

| (0.945) | ||||||||

| (3) Growth Mindset: Instability | 212 | 2.16 | 0.147 * | 0.180 * | ||||

| (0.030) | (0.009) | |||||||

| (4) Growth Mindset: Malleability | 212 | 2.25 | 0.070 | 0.121 | 0.636 * | |||

| (0.304) | (0.081) | (0.000) | ||||||

| (5) Mastery Goal | 135 | 3.93 | −0.122 | 0.431 * | 0.134 | 0.121 | ||

| (0.159) | (0.000) | (0.121) | (0.163) | |||||

| (6) Performance Approach | 135 | 2.79 | −0.215 * | 0.091 | 0.052 | −0.041 | 0.327 * | |

| (0.012) | (0.294) | (0.552) | (0.634) | (0.000) | ||||

| (7) Performance Avoid | 135 | 2.74 | −0.160 | 0.029 | 0.167 | 0.026 | 0.305 * | 0.628 * |

| (0.064) | (0.736) | (0.053) | (0.769) | (0.000) | (0.000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hutchins, N.; Jirout, J. Understanding Motivation in Early Childhood: Disentangling the Links Among Curiosity, Mindset, and Goals. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010054

Hutchins N, Jirout J. Understanding Motivation in Early Childhood: Disentangling the Links Among Curiosity, Mindset, and Goals. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutchins, Natalie, and Jamie Jirout. 2026. "Understanding Motivation in Early Childhood: Disentangling the Links Among Curiosity, Mindset, and Goals" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010054

APA StyleHutchins, N., & Jirout, J. (2026). Understanding Motivation in Early Childhood: Disentangling the Links Among Curiosity, Mindset, and Goals. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010054