4.1. Language Control via Phonological Activation of Translation Equivalents

The results from Experiment 1A demonstrated the influence of the picture naming task on the subsequent performance on the Chinese phonological judgement task. L1 naming significantly facilitated the performance relative to the baseline condition (0 naming trials), in which participants exhibited shorter RTs and higher ACC when judging the phonological relationships between the cues and target picture names after engaging in L1 naming. This finding directly validates the effectiveness of the experiment’s design, as it confirms that L1 naming modulates the accessibility of phonological representations in a manner that translates to improved performance on a downstream phonological processing task. Specifically, the act of naming pictures in L1 increased the activation level of the Chinese phonological representations corresponding to the target pictures, which reduced the cognitive effort required to identify the phonological relationships during the judgement task, thereby leading to superior performance.

A more striking and theoretically informative finding was that L2 naming also facilitated performance on the Chinese phonological judgment task, mirroring the facilitatory effect observed with L1 naming. This result provides compelling evidence that naming pictures in the L2 not only activates the phonological representations of the target English words, but it also enhances the accessibility of phonological representations corresponding to their L1 (Chinese) translation equivalents. Such robust cross-language phonological activation aligns with the converging predictions of the Interactive Activation Model and the Language-Specific Selection Model, offering a coherent mechanistic account of the observed facilitation.

The Interactive Activation Model serves as a foundational framework here, as it posits that not only the target lemma, but also other co-activated lemmas in lexical selection gain access to the phonological encoding stage, enabling the simultaneous activation of multiple phonological representations. Specifically, the model argues that activating a target word’s phonological representation in one language triggers the phonological activation of its translation equivalent. Complementing this, the Language-Specific Selection Model clarifies the critical role of language-specific competition constraints. Notably, the present study extended the original Language-Specific Selection Model to the phonological level. The Language-Specific Selection Model originally proposed that within-language competition occurs at lexical selection, with non-target language lemmas not inhibited but rather excluded from selection. Extending this to the phonological level, non-target language phonological representations are not inhibited but remain activated.

Taken together, these two models synergistically explain the observed facilitation effect in the Chinese phonological judgment task. When participants named pictures in L2, the Interactive Activation Model led to co-activation of the phonological representations of L2 target words and their L1 translation equivalents. Crucially, under the extended Language-Specific Selection Model’s framework, this cross-language activation did not incite between-language competition during phonological encoding. As a result, the activated L1 phonological representations remained functionally accessible and were not subjected to inhibitory suppression. When participants subsequently completed the Chinese phonological judgment task, these pre-activated L1 phonological representations conferred a processing advantage: the prior activation reduced the cognitive effort required to retrieve or verify the phonological relationship between the cues and the L1 translation equivalents, leading to faster RTs and higher ACCs relative to the baseline condition where no prior naming trials had primed the L1 representations.

This pattern of results reinforces the compatibility of the Interactive Activation Model’s non-selective activation account and the Language-Specific Selection Model’s language-specific competition principle. It further highlights that cross-language activation does not inherently lead to interference; instead, the scope of competition determines whether activated non-target representations will hinder or assist subsequent processing. In this case, the absence of cross-language competition allowed the pre-activated L1 phonological representations to serve as a processing scaffold, rather than a competing distraction, thereby enhancing performance on the L1 phonological judgment task.

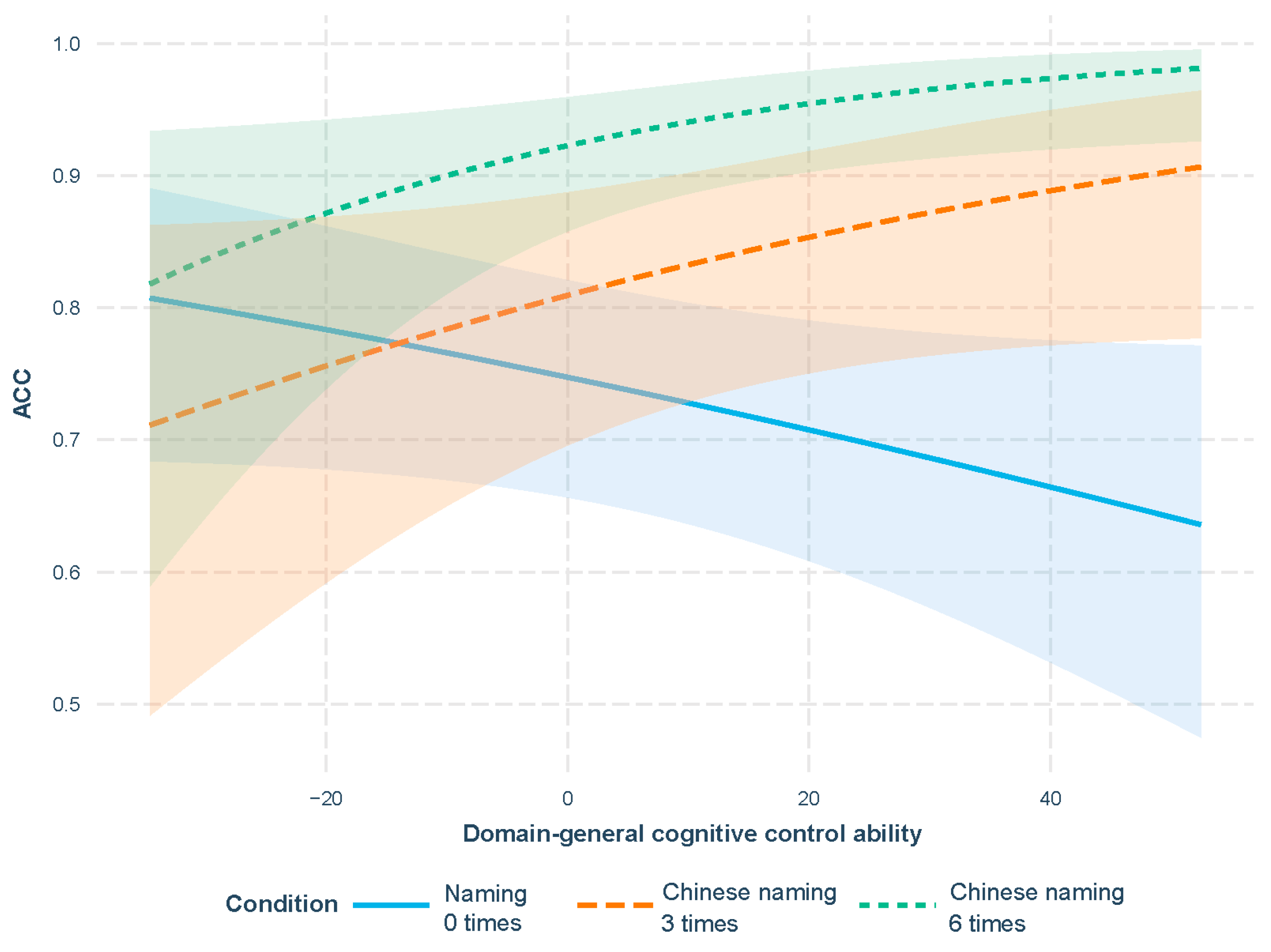

Further nuanced analysis of the naming time effects revealed an important boundary condition to this facilitatory pattern: significant differences in phonological judgement performance were observed between naming 3 times and naming 0 times, but no significant differences emerged between the naming 3 times and naming 6 times. One plausible explanation for this ceiling effect is that 3 naming trials were sufficient to elevate the activation level of both the target language phonological representations and their translation equivalents to a near-maximal level. Additional naming trials (i.e., increasing from 3 times to 6 times) did not provide further activation gains, as the representations had already reached a threshold where additional exposure did not translate to measurable improvements in downstream task performance.

Experiment 1B yielded results consistent with those of Experiment 1A, providing converging evidence that language control during phonological encoding in L1 production adheres to the combined framework of the Interactive Activation Model and the Language-Specific Selection Model. Specifically, Experiment 1B demonstrated that L1 picture naming coactivated the phonological representations of the corresponding L2 translation equivalents. However, competitive processes during phonological encoding were exclusively restricted to the target language, meaning that the coactivated L2 phonological representations did not compete with L1 target representations for selection.

Beyond replicating the core findings, Experiment 1B demonstrated overall higher ACC than Experiment 1A, which initially appeared counterintuitive given the tasks’ language contexts. Experiment 1B implemented an L2 (English) phonological judgement task, whereas Experiment 1A featured an L1 (Chinese) phonological judgement task. Conventionally, one would anticipate superior performance in L1 tasks, as L1 represented the dominant language for all participants in this study. This unexpected pattern, however, can be unpacked through an analysis of language-specific orthographical–phonological consistency and the strategic deployment of orthographic cues during phonological evaluation. In Experiment 1B, phonological cues were delivered in written form, enabling the participants to utilize orthographic representations as a supportive cue for accessing and evaluating L2 phonological targets. Specifically, the participants could align these orthographic cues with the L2 names of the pictures they had previously named due to English’s inherent properties as an alphabetic language. English exhibits strong mapping between orthographic and phonological outputs. In contrast, Experiment 1A relied on Chinese, a logographic language, where the connection between orthographic and phonological representations is far less systematic. Unlike alphabetic systems, Chinese characters do not encode phonological information through consistent letter–sound correspondences. This weak orthographical–phonological association diminished the utility of orthographic cues for L1 phonological judgement, contributing to the lower ACC observed in Experiment 1A.

In addition, Experiment 1B also identified a novel moderating role of the participants’ domain-general cognitive control ability, in which the participants with higher domain-general cognitive control ability presented a larger facilitation effect on ACC. One possible explanation involved domain-general proactive control. Proactive control refers to “a sustained and anticipatory mode of control that is goal-directed, allowing individuals to actively and optimally configure processing resources prior to the onset of task demands” (

Tang et al., 2022, p. 1457). As L2 represents the non-dominant language for all the participants, the L2 phonological judgement task was perceived as more cognitively demanding than the L1 phonological judgement task in Experiment 1A. This perceived difficulty motivated the participants to actively allocate greater cognitive effort to task engagement and goal maintenance before they started L2 task. Therefore, the participants with stronger domain-general cognitive control exhibited superior performance in the L2 task.

The current study’s findings align with those of

Linck (

2008) and

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012) as all three studies demonstrated that performance on a target language phonological judgement task can be facilitated by prior picture naming in either the target language or a non-target language. However, the current work extends these prior results by addressing key gaps in their samples and task designs.

Linck (

2008) conducted four experiments with English–Spanish and Spanish–English bilinguals, investigating both L2 and L1 production effects but focusing exclusively on Indo-European language pairs.

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012) used Spanish–English and Spanish–Catalan bilinguals spanning multiple L2 proficiency levels but limited their analysis to L2 production. The current study complemented these efforts by extending the facilitatory effect to distinct-script bilinguals and examining both L1 and L2 production contexts, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the facilitation effects. Beyond empirical extensions, the current study also offers a unique theoretical account that diverges from the explanations proposed by

Linck (

2008) and

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012).

Linck (

2008) advanced two tentative interpretations for their facilitatory effects: either (1) language production does not involve inhibitory mechanisms, or (2) inhibition exists but remains undetected due to task-specific factors, such as naming repetition counts and participant L2 proficiency. This account lacked clarity regarding the role of inhibition in phonological encoding.

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012), by contrast, framed their results as support for the Feature Suppression Model, which posits that inhibition and activation co-occur during memory retrieval: semantically related representations share some features, which drive facilitation and differ in others, triggering inhibition, with the final outcome reflecting a trade-off between these two processes. This model predicts that facilitation should dominate when retrieving words in Language A after practicing them in Language B, which is consistent with their findings. However,

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012) acknowledged that this account “remains silent about how the bilingual speaker manages to restrict language production to only one language” (p. 10). In response to these accounts, the current study proposes an alternative framework that integrates the Interactive Activation Model and the Language-Specific Selection Model. Notably, it is acknowledged that bilingual language production is a complex process requiring the coordination of multiple cognitive mechanisms. Future research is needed to disentangle the contributions of distinct cognitive mechanisms and to explore their dynamic interactions during bilingual language production.

A further critical point of comparison is the divergence between the current study and

Levy et al. (

2007).

Levy et al. (

2007) observed interference in L1 phonological judgement after repeated L2 naming, whereas the current study found facilitation. To explore the potential sources of this discrepancy, three key task and sample differences were examined. First, the number of naming repetitions varied.

Levy et al. (

2007) implemented 0, 1, 5, or 10 naming times, while the current study used 0, 3, or 6 times. Although one might hypothesize that more repetitions could elicit inhibition,

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012) also used 0, 1, 5, or 10 times and still observed facilitation, ruling out repetition count as a sole driver of interference. Second, the participants’ L2 proficiency differed.

Levy et al. (

2007) focused on low-proficiency bilinguals, while the current study included medium-to-high proficiency participants. Again, this cannot fully explain the discrepancy, as

Runnqvist and Costa (

2012) included bilinguals across low, medium, and high proficiency levels and consistently found facilitation. Third,

Levy et al. (

2007) relied solely on ACC, while the current study incorporated both RTs and the ACC as dependent variables. As noted in prior research (

Veling & van Knippenberg, 2004), RTs and ACC together provide a more sensitive index of underlying cognitive processes than ACC alone. Whereas the ACC captures the accuracy of performance, RTs reflect the efficiency of cognitive processing, enabling detection of subtle effects that may not manifest as errors but instead as delays in resolving interference. Collectively, these analyses suggest that the current study not observing interference effects is not attributable to these task or sample factors but instead provides evidence that the phonological representations of translation equivalents are not inhibited during bilingual production. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to confirm whether inhibition is truly unnecessary for phonological control in bilinguals or simply remains undetected under certain experimental conditions.

4.2. Language Control via Cross-Language Phonological Similarity

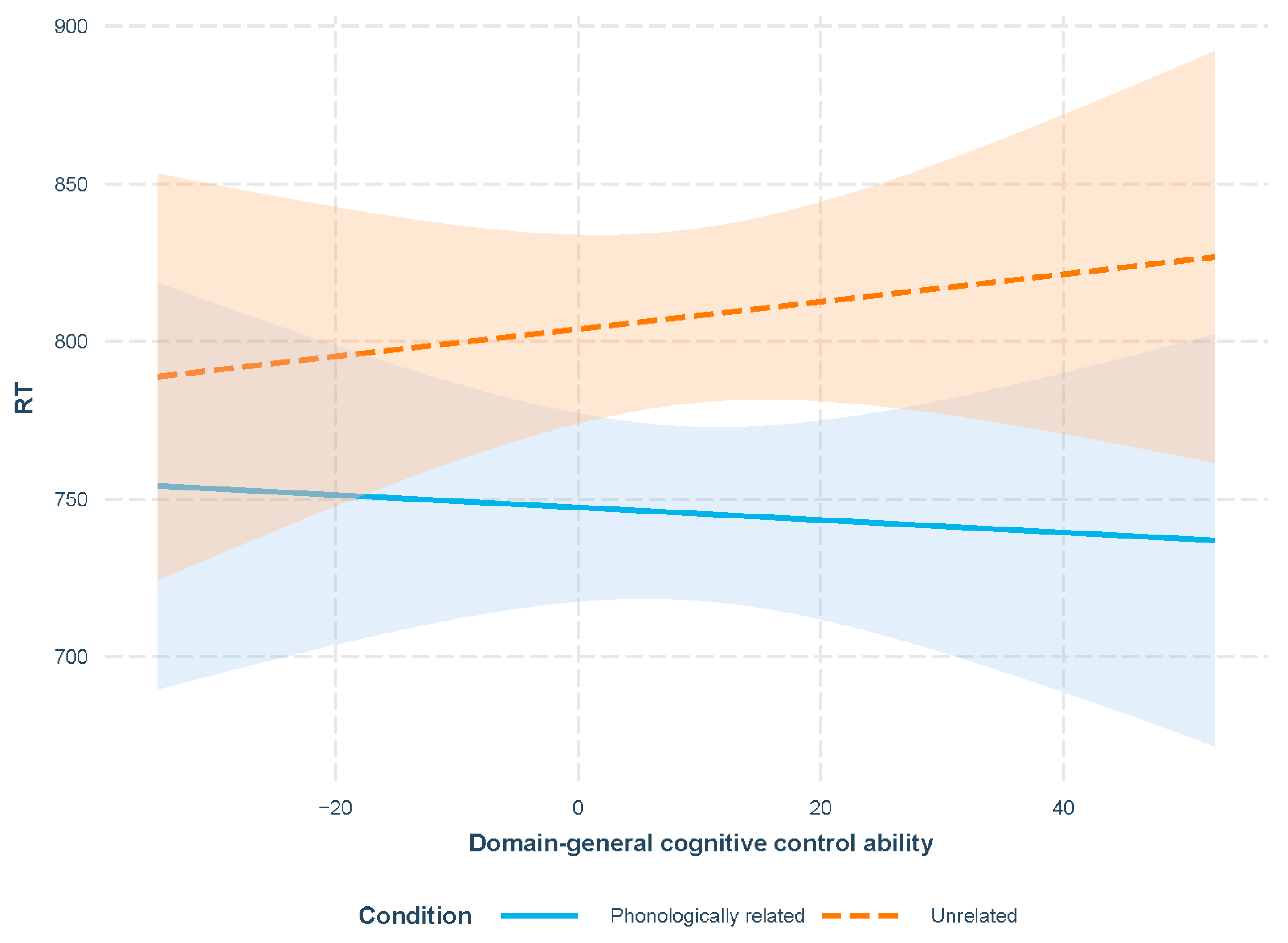

Experiments 2A and 2B both yielded consistent cross-language phonological facilitation effects, in which the participants named pictures significantly faster when presented with cross-language phonologically related distractors than with unrelated distractors. These findings provide empirical support for the Language-Specific Selection Model. Since the original Language-Specific Selection Model was originally developed to account for processes at the lexical selection stage, its core principles should be extended to phonological encoding. A refined theoretical account rooted in Language-Specific Selection Model’s core principles was proposed to illustrate the language control mechanism underlying phonological encoding. Specifically, when a bilingual speaker engages in the phonological encoding of a target word, the activation of the target’s phonological representation triggers the activation of phonologically related representations in the non-target language. Critically, however, phonological selection is restricted to the target language, suggesting that phonological representations in non-target language do not compete with target representations. The facilitation effects become transparent when viewed through this revised Language-Specific Selection Model lens. In the two experiments, participants were presented with phonologically similar distractors in the non-target language. These visual distractors amplified the activation level of their phonological representations. Importantly, because the phonological selection was language-specific, the activated phonological representations in the non-target language did not compete with the target phonological representation. Instead, the phonological similarity between the two enhanced activation transmission, accelerating the encoding of the target’s phonological representation. This facilitation effect was particularly pronounced in the current study due to the high degree of phonemic overlap between the picture names and distractors across languages. For instance, the L1 Chinese character “币” (coin) has a phonological structure of /b/ + /ɪ/, while its L2 English distractor “bee” consists of /b/ + /iː/, which is a near-perfect phonemic correspondence in terms of consonant and vowel quality and syllabic structure. Such close cross-language alignment maximized the activation spread between related representations, amplifying the observed facilitation effect. Consequently, activated phonological representations in the non-target language functioned as a source of activation reinforcement rather than competitors for target representations.

In addition to the facilitation effects, Experiment 2A revealed a significant interaction between cross-language phonological relatedness and domain-general cognitive control ability. Specifically, as the participants’ domain-general cognitive control ability increased, the magnitude of the cross-language facilitation effect in L2 production became significantly larger. Notably, this interaction was absent in Experiment 2B, which is an L1 production task. As hypothesized in prior analyses of Experiment 1B, the interaction likely reflects the involvement of proactive control. For the participants, L2 functions as the non-dominant language, meaning L2 production tasks are perceived as more cognitively demanding than L1 production tasks. This heightened perceived difficulty made participants proactively allocate greater cognitive effort to maintaining the task goal in L2 tasks, resulting in a detectable influence of domain-general cognitive control ability in L2 production but not in L1 production.

The current findings align with prior studies (

Costa et al., 2003;

Costa & Caramazza, 1999;

Hermans et al., 1998) while diverging from others (

Boukadi et al., 2015;

Hoshino & Thierry, 2011;

Hoshino et al., 2021).

Hoshino and Thierry (

2011) attributed their failure to observe facilitation to the use of repeated picture names as distractors.

Boukadi et al. (

2015) documented interference effects in Tunisian Arabic–French bilinguals, proposing that phonological dissimilarity between the two languages drove this outcome. Specifically, they argued that phonemes perceived as closely related yet distinct enough to trigger competition between lexical representations, resulting in interference. They also hypothesized that, with the increase in L2 proficiency, such an interference effect should be decreased or even eliminated. Their account centers on phonological dissimilarity as a critical moderator, and greater sensitivity to such differences enables more effective language differentiation, thereby mitigating non-target language interference. Inspired by

Boukadi et al. (

2015), the present study proposes another potential explanation. While the Language-Specific Selection Model, with the prerequisite that phonological representations have distinct language tags, can account for the facilitation effect observed, we can also consider a scenario where this prerequisite is given up. For the participants, cross-language phonemes with high similarity may lack clear language tagging. When phonemic overlap is substantial yet distinct and not sufficient to induce competition, then facilitation arises. An extreme situation was that the two similar phonemes were totally undistinguishable for our participants. This alternative explanation is consistent with the Speech Learning Model (

Flege, 1995). This model posits that L2 sounds resembling L1 phonemes may fail to be perceptually discriminated by late bilinguals, leading to merged phonological representations. Given the sample of late medium–high proficiency bilinguals in the present study, such merging is plausible, potentially explaining why similar phonemes across languages amplified, rather than disrupted, target processing.

Hoshino et al. (

2021) observed facilitation in Spanish–English bilinguals but not in Japanese–English bilinguals, attributing this contrast to script specificity. Distinct writing systems act as early language cues, directing attention to the target language. This aligns with the principle of nonselective activation with language-specific selection mechanisms. Notably, their framework also assumes competition is restricted to the target language, and the non-target language does not exert influence on the target language, corresponding to the null effects. However, this cannot fully account for the facilitation effects in the present study. The present study posits that facilitation can be attributed to an additional process in which the activation of distractor phonemes exerts a facilitatory effect on their cross-language analogous phonemes, which form the targets. This process parallels the explanation provided by the Language-Specific Selection model for the robust translation facilitation observed in the bilingual PWI paradigm, wherein target words enhance the activation of their translation equivalents. The present study draws a direct analogy between the lexical-level relationship of words and their translations and the phonological-level association of phonemes and their cross-language counterparts. Such a process possibly also emerges in

Hoshino et al. (

2021), yet the contrast between their null effects and the current facilitation findings is likely rooted in stimulus design.

Hoshino et al.’s (

2021) materials featured partial phonological overlap (e.g., English “envelope” /ˈenvəloʊp/ and Japanese “煙突” /eNtotu/ [chimney]), whereas our stimuli paired monosyllabic Chinese characters with English words (e.g., “币” /bɪ/ and “bee” /biː/) exhibiting extensive vowel and consonant overlap. This greater phonemic correspondence may have amplified facilitatory activation in the present study.