The Longitudinal Impact of Father Presence on Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Between Father Presence and Depressive Symptoms

1.2. The Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs

1.3. The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation Strategies

1.4. Chain Mediation of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation Strategies

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Father Presence

2.2.2. Emotion Beliefs

2.2.3. Emotion Regulation

2.2.4. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Analysis Plan

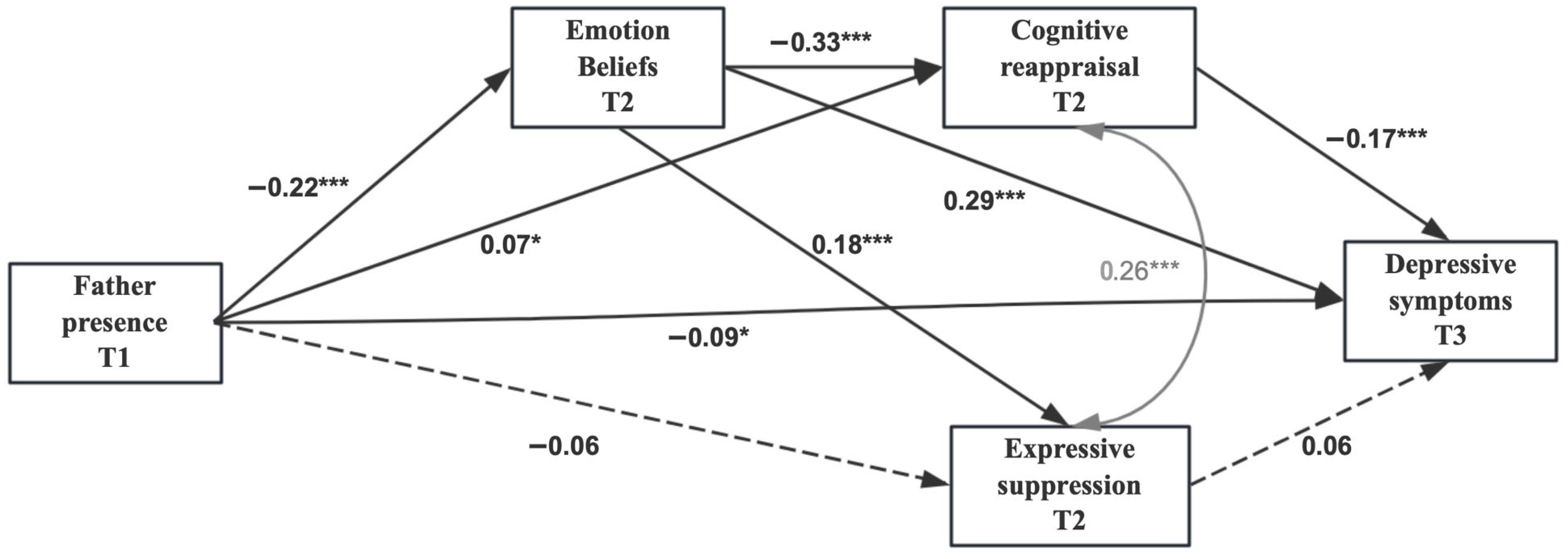

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Primary Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Father Presence on Depressive Symptoms

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Emotion Beliefs

4.3. The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation

4.4. The Sequential Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation

4.5. Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrocas, J., Vieira-Santos, S., Paixão, R., Roberto, M. S., & Pereira, C. R. (2017). The “Inventory of father involvement–Short form” among Portuguese fathers: Psychometric properties and contribution to father involvement measurement. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 18(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, R., Preece, D. A., & Gross, J. J. (2020). Assessing beliefs about emotions: Development and validation of the emotion beliefs questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Volume 1: Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 993–1028). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, E. A., Lee, T. L., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion, 7(1), 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Xu, C., Li, Q., Lu, S., & Xiao, J. (2024). Factor structure and longitudinal invariance of the CES-D across diverse residential backgrounds in Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 26(4), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. M. Y., Hong, R. Y., Ong, X. L., & Cheung, H. S. (2023). Emotion dysregulation and symptoms of anxiety and depression in early adolescence: Bidirectional longitudinal associations and the antecedent role of parent-child attachment. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 41(3), 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. J., Halpern, C. T., & Kaufman, J. S. (2007). Maternal depressive symptoms, father’s involvement, and the trajectories of child problem behaviors in a U.S. national sample. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(7), 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S. C., Bai, S., Mak, H. W., & Fosco, G. M. (2024). Dynamic characteristics of parent–adolescent closeness: Predicting adolescent emotion dysregulation. Family Process, 63(4), 2243–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Kim, H. K., Capaldi, D. M., & Snodgrass, J. J. (2021). Long-term effects of father involvement in childhood on their sons’ physiological stress regulation system in adulthood. Developmental Psychobiology, 63(6), e22152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, E. Z., Cai, Y. Y., Wang, Y., & Wu, Y. (2021). Association of depression and suicidal ideation with parenting style in adolescents. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 23(9), 938–943. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E., Branje, S., Rubini, M., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2017). Identity processes and parent–child and sibling relationships in adolescence: A five-wave multi-informant longitudinal study. Child Development, 88(1), 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culpin, I., Heron, J., Araya, R., Melotti, R., & Joinson, C. (2013). Father absence and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Findings from a UK cohort. Psychological Medicine, 43(12), 2615–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culpin, I., Heuvelman, H., Rai, D., Pearson, R. M., Joinson, C., Heron, J., Evans, J., & Kwong, A. S. F. (2022). Father absence and trajectories of offspring mental health across adolescence and young adulthood: Findings from a UK birth cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 314, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X., Sang, B., & Chen, X. (2017). Implicit beliefs about emotion regulation and their relations with emotional experiences among Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(2), 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, E., Brandão, T., Monteiro, L., & Veríssimo, M. (2021). Father involvement during early childhood: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., & Spinrad, T. L. (1998). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 241–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faden, V. B., Day, N. L., Windle, M., Windle, R., Grube, J. W., Molina, B. S. G., Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E. M., Wilson, T. K., Jackson, K. M., & Sher, K. J. (2004). Collecting longitudinal data through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood: Methodological challenges. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(2), 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., & Gross, J. J. (2018). Emotion regulation: Why beliefs matter. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 59(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Why beliefs about emotion matter: An emotion-regulation perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(1), 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., Lwi, S. J., Gentzler, A. L., Hankin, B., & Mauss, I. B. (2018). The cost of believing emotions are uncontrollable: Youths’ beliefs about emotion predict emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(8), 1170–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X., Jiao, R., & Wang, J. (2024). Connections between parental emotion socialization and internalizing problems in adolescents: Examining the mediating role of emotion regulation strategies and moderating effect of gender. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Zheng, H., Ruan, D., Hu, D., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., & Chan, R. C. K. (2023). Cognitive and affective empathy and negative emotions: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 55(6), 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B., Fan, J., Liu, N., Li, H., Wang, Y., Williams, J., & Wong, K. (2012). Depression risk of “left-behind children” in rural China. Psychiatry Research, 200(2–3), 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanski, A., Lichtenstein, L., Mühling, L. E., & Zimmermann, P. (2021). Effects of father and mother attachment on depressive symptoms in middle childhood and adolescence: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Brain Sciences, 11(9), 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., Tang, X., Lin, Z., Lin, Y., & Hu, Z. (2024). Father’s involvement associated with rural children’s depression and anxiety: A large-scale analysis based on data from seven provinces in China. Global Mental Health, 11, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Yang, D., Li, Y., & Yuan, J. (2021). The influence of pubertal development on adolescent depression: The mediating effects of negative physical self and interpersonal stress. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 786386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Kim, S., & Yoon, S. (2024). Emotion malleability beliefs matter in emotion regulation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 38(6), 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kneeland, E. T., & Simpson, L. E. (2022). Emotion malleability beliefs influence emotion regulation and emotion recovery among individuals with depressive symptoms. Cognition and Emotion, 36(8), 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneeland, E. T., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Dovidio, J. F., & Gruber, J. (2016). Emotion malleability beliefs influence the spontaneous regulation of social anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(4), 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kökönyei, G., Kovács, L. N., Szabó, J., & Urbán, R. (2024). Emotion regulation predicts depressive symptoms in adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(1), 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krampe, E. M., & Newton, R. R. (2006). The father presence questionnaire: A new measure of the subjective experience of being fathered. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research & Practice about Men as Fathers, 4(2), 159–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwete, X., Knaul, F. M., Essue, B. M., Touchton, M., Arreola-Ornelas, H., Langer, A., Calderon-Anyosa, R., & Nargund, R. S. (2024). Caregiving for China’s one-child generation: A simulation study of caregiving responsibility and impact on women’s time use. BMJ Global Health, 9(6), e013400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Ying, P., & Tan, J. (2019). Reliability and validity of the short version of the father presence questionnaire among adolescents. China Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., Li, W., Lei, J., Han, X., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Q., Gong, J., Zhang, J., Chen, Z., & Feng, Z. (2025). Perceived parental involvement decreases the risk of adolescent depression. Alpha Psychiatry, 26(4), 46110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, F. T., Halberstadt, A. G., Craig, A. B., Dennis, P. A., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2016). Parents’ beliefs about children’s emotions and parents’ emotion-related conversations with their children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B., Lin, L., & Su, X. (2024). Global burden of depression or depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 354, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, F., & Wang, Z. (2024). Trends in mental health: A review of the most influential research on depression in children and adolescents. Annals of General Psychiatry, 23(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D. A. (2014). Missing data: Five practical guidelines. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 372–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S., Riddle, O. S., Oliver, B. R., & Somerville, M. P. (2025). Understanding the development of depression through emotion beliefs, emotion regulation, and parental socialisation. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 25602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2017). Enhancing father involvement in low-income families: A couples group approach to preventive intervention. Child Development, 88, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, N., Rattaz, V., Favez, N., & Tissot, H. (2024). Father involvement and emotion regulation during early childhood: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R. M., Oar, E. L., Johnco, C. J., Forbes, M. K., Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., & Richardson, C. E. (2019). Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Robinson, E. L., StGeorge, J., & Freeman, E. E. (2021). A systematic review of father-child play interactions and the impacts on child development. Children, 8(5), 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, J. Ö., Naumann, E., Holmes, E. A., Tuschen-Caffier, B., & Samson, A. C. (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(2), 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, M. P., MacIntyre, H., Harrison, A., & Mauss, I. B. (2024). Emotion controllability beliefs and young people’s anxiety and depression symptoms: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 9(1), 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamir, M., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W., Weiss, B., Kim, J. H. J., & Lau, A. S. (2021). Longitudinal relations between emotion restraint values, life stress, and internalizing symptoms among Vietnamese American and European American adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 50(5), 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Lopez, C., Sokol, N. A., Bublitz, M. H., Gaffey, A. E., Gomez, A., Mercado, N., Silk, J. S., & Stroud, L. R. (2024). Exploring the impact of maternal and paternal acceptance on adolescent girls’ emotion regulation. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 55(2), 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Liu, H., Li, Z., & Du, W. (2007). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the emotion regulation questionnaire. China Journal of Health Psychology, 15(6), 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Liang, Y., Zhou, N., & Zou, H. (2019). Chinese fathers’ emotion socialization profiles and adolescents’ emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T. L., Miles, E., & Sheeran, P. (2012). Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 775–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., Zhuang, M., & Xue, L. (2023). Father presence and resilience of Chinese adolescents in middle school: Psychological security and learning failure as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1042333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key variables | ||||||||||||

| 1. Father presence T1 | 3.52 | 0.67 | – | |||||||||

| 2. Emotion beliefs T2 | 2.26 | 1.04 | −0.23 ** | – | ||||||||

| 3. Cognitive reappraisal T2 | 4.96 | 1.28 | 0.15 ** | −0.35 ** | – | |||||||

| 4. Expressive suppression T2 | 3.64 | 1.30 | −0.10 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.17 ** | – | ||||||

| 5. Depressive symptoms T3 | 1.95 | 0.54 | −0.20 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.28 ** | 0.10 ** | – | |||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| 6. Family income | 4.03 | 1.09 | 0.11 ** | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.08 * | – | ||||

| 7. Mom education | 2.87 | 0.93 | 0.10 ** | 0.004 | 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.08 * | 0.27 ** | – | |||

| 8. Dad education | 2.97 | 0.89 | 0.15 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.08 * | 0.26 ** | 0.61 ** | – | ||

| 9. Age | 16.06 | 0.43 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.07 * | −0.02 | −0.06 | – | |

| 10. Gender | −0.14 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.07 * | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.05 | – |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||

| Effect | β | LL | UL | β | LL | UL | β | LL | UL |

| Direct | |||||||||

| Father presence T1 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.20 *** | −0.26 | −0.13 | −0.10 ** | −0.17 | −0.03 | −0.14 *** | −0.21 | −0.07 |

| Indirect | |||||||||

| Father presence T1 → Emotion beliefs T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.08 *** | −0.11 | −0.05 | ||||||

| Father presence T1 → Cognitive reappraisal T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.04 *** | −0.06 | −0.02 | ||||||

| Father presence T1 → Expressive suppression T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Model D (Parallel Model) | Model E (Serial Model) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

| Effect | β | LL | UL | β | LL | UL |

| Direct | ||||||

| Father presence T1 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.09 * | −0.15 | −0.02 | −0.09 * | −0.15 | −0.02 |

| Indirect | ||||||

| Father presence T1 → Emotion beliefs T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.07 *** | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.07 *** | −0.09 | −0.04 |

| Father presence T1 → Cognitive reappraisal T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.03 ** | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 * | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| Father presence T1 → Expressive suppression T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| Father presence T1 → Emotion beliefs T2 → Cognitive reappraisal T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.01 *** | −0.02 | −0.01 | |||

| Father presence T1 → Emotion beliefs T2 → Expressive suppression T2 → Depressive symptoms T3 | −0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, D.; Peng, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. The Longitudinal Impact of Father Presence on Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010047

Xu D, Peng H, Zhou Z, Wang J. The Longitudinal Impact of Father Presence on Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Dan, Haowen Peng, Zongkui Zhou, and Jing Wang. 2026. "The Longitudinal Impact of Father Presence on Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010047

APA StyleXu, D., Peng, H., Zhou, Z., & Wang, J. (2026). The Longitudinal Impact of Father Presence on Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Emotion Beliefs and Emotion Regulation. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010047