The Impact of Test Anxiety and Cognitive Stress on Error-Related Brain Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. TAS

2.2.2. Subjective Test Anxiety Scale (STAS)

2.2.3. Short State Anxiety Inventory (SSAI)

2.2.4. Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (RSPM)

2.2.5. Flanker Task

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Electrophysiological Recording and Data Reduction

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Self-Reports

3.1.1. STAS

3.1.2. SSAI

3.2. Behavioral Data

3.2.1. RTs

3.2.2. Accuracy

3.2.3. Post-Error Slowing

3.3. Error-Related Brain Activity and Anxiety

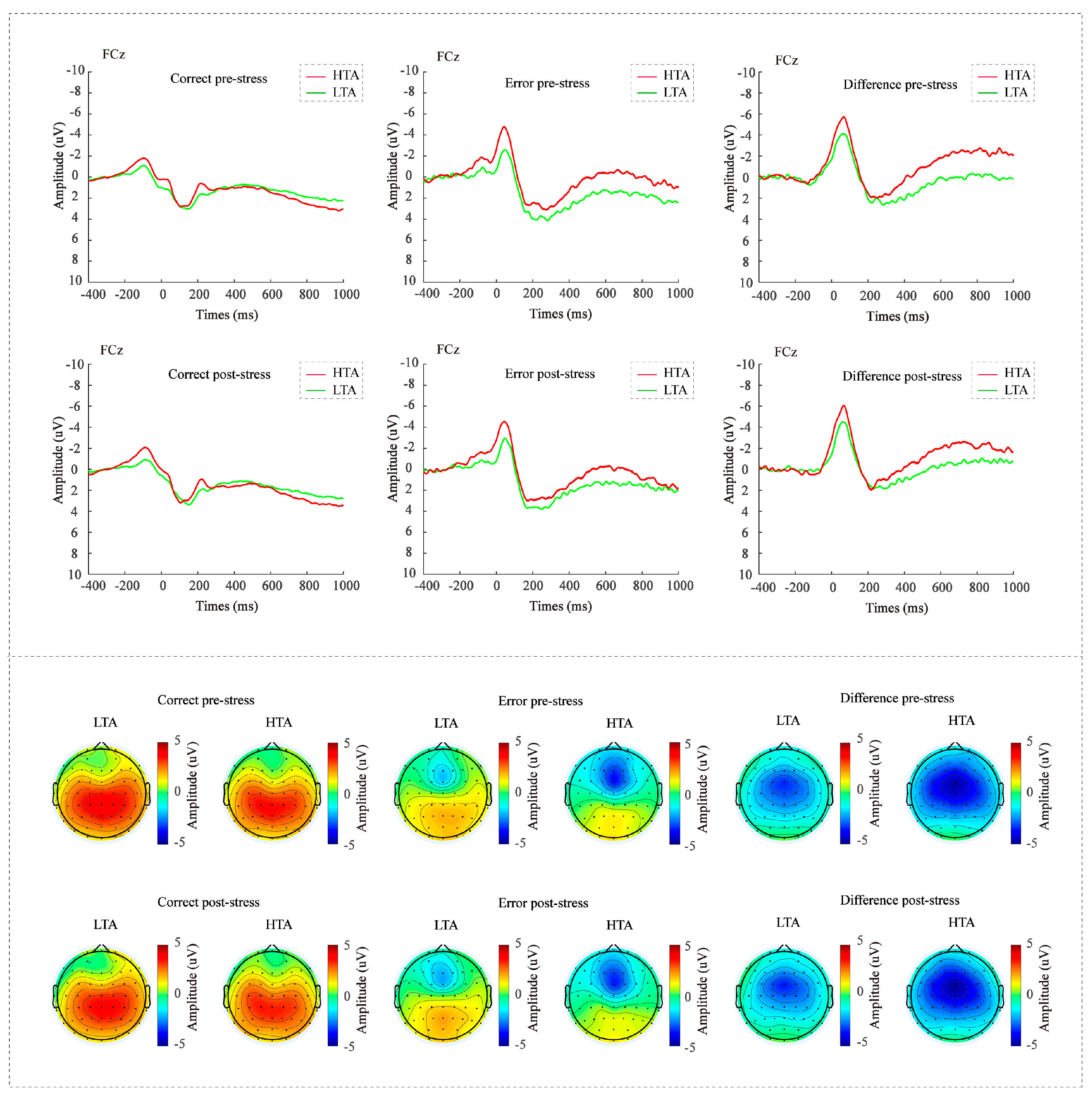

3.3.1. Three-Way ANOVA on ERN and CRN

3.3.2. ΔERN

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ERN | Error-related negative |

| CRN | Correct-response negativity |

| HTA | High test anxiety |

| LTA | Low test anxiety |

| RTs | Reaction times |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| TAS | Test Anxiety Scale |

| STAS | Subjective test anxiety scale |

| SSAI | Short state anxiety inventory |

| RSPM | Raven’s standard progressive matrices |

References

- Amir, N., Holbrook, A., Kallen, A., Santopetro, N., Klawohn, J., McGhie, S., Bruchnak, A., Lowe, M., Taboas, W., Brush, C. J., & Hajcak, G. (2024). Multiple adaptive attention-bias-modification programs to alter normative increase in the error-related negativity in adolescents. Clinical Psychological Science, 12(3), 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogun, A. G., Balogun, S. K., & Onyencho, C. V. (2017). Test anxiety and academic performance among undergraduates: The moderating role of achievement motivation. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20(e14), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basten, U., Stelzel, C., & Fiebach, C. J. (2011). Trait anxiety modulates the neural efficiency of inhibitory control. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(10), 3132–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnefond, A., Doignon-Camus, N., Hoeft, A., & Dufour, A. (2011). Impact of motivation on cognitive control in the context of vigilance lowering: An ERP study. Brain and Cognition, 77(3), 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108(3), 624–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázdil, M., Roman, R., Daniel, P., & Rektor, I. (2005). Intracerebral error-related negativity in a simple Go/NoGo task. Journal of Psychophysiology, 19(4), 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R. J., & Buss, K. A. (2014). Harsh parenting and fearfulness in toddlerhood interact to predict amplitudes of preschool error-related negativity. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 9, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caikang, W. (2001). Reliability and validity of test anxiety scale-chinese version. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 15(2), 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M. G., Ramos, P. M., & Estevez, A. (1992). Test anxiety and comprehension efficiency: The role of prior knowledge and working memory deficits. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 5(2), 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, M., Harbin, S. M., Nienhuis, J. K., Fitzgerald, K. D., Gehring, W. J., & Hanna, G. L. (2013a). Increased error-related brain activity in youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder and unaffected siblings. Depression anxiety, 30(1), 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, M., Hong, C., Nienhuis, J. K., Harbin, S. M., Fitzgerald, K. D., Gehring, W. J., & Hanna, G. L. (2013b). Increased error-related brain activity in youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety disorders. Neuroscience Letters, 541, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(2), 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J. F., & Allen, J. J. B. (2008). Multiple aspects of the stress response under social evaluative threat: An electrophysiological investigation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(1), 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Itier, R. J. (2024). No association between error-related ERP s and trait anxiety in a nonclinical sample: Convergence across analytical methods including mass-univariate statistics. Psychophysiology, 61(11), e14645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L. J., & Meyer, A. (2019). Understanding the link between anxiety and a neural marker of anxiety (the error-related negativity) in 5 to 7 year-Old children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 44(1), 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, L. J., Mirzadegan, I. A., & Meyer, A. (2020). The association between parenting and the error-related negativity across childhood and adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 45, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. L., Mehra, L. M., Cibrian, E., Cummings, E. M., Nelson, B. D., Hajcak, G., & Meyer, A. (2023). Relational victimization prospectively predicts increases in error-related brain activity and social anxiety in children and adolescents across two years. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 61, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coles, M. G. H., Scheffers, M. K., & Holroyd, C. B. (2001). Why is there an ERN/Ne on correct trials? Response representations, stimulus-related components, and the theory of error-processing. Biological Psychology, 56(3), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derakshan, N., Ansari, T. L., Hansard, M., Shoker, L., & Eysenck, M. W. (2009). Anxiety, inhibition, efficiency, and effectiveness. An investigation using the antisaccade task. Experimental Psychology, 56(1), 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive Functions. In S. T. Fiske (Ed.), Annual review of psychology (Vol. 64, pp. 135–168). Annual Reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y., De Beuckelaer, A., Yu, L., & Zhou, R. (2017). Eye-movement evidence of the time-course of attentional bias for threatening pictures in test-anxious students. Cognition Emotion, 31(4), 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrass, T., Klawohn, J., Schuster, F., & Kathmann, N. (2008). Overactive performance monitoring in obsessive-compulsive disorder: ERP evidence from correct and erroneous reactions. Neuropsychologia, 46(7), 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 16(1), 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M. W., & Derakshan, N. (2011). New perspectives in attentional control theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(7), 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenstein, M., Hohnsbein, J., Hoormann, J., & Blanke, L. (1991). Effects of crossmodal divided attention on late ERP components. II. Error processing in choice reaction tasks. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 78(6), 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenstein, M., Hoormann, J., Christ, S., & Hohnsbein, J. (2000). ERP components on reaction errors and their functional significance: A tutorial. Biological Psychology, 51(2–3), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, N. P., & Miyake, A. (2004). The relations among inhibition and interference control functions: A latent-variable analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General, 133(1), 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, W. J., Goss, B., Coles, M. G. H., Meyer, D. E., & Donchin, E. (1993). A neural system for error-detection and compensation. Psychological Science, 4(6), 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, W. J., Himle, J., & Nisenson, L. G. (2000). Action-monitoring dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Science, 11(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, W. J., Liu, Y., Orr, J. M., & Carp, J. (2011). The error-related negativity (ERN/Ne). In S. J. Luck, & E. S. Kappenman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of event-related potential components (pp. 231–291). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak, G. (2012). What we’ve learned from mistakes: Insights from error-related brain activity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(2), 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajcak, G., & Foti, D. (2008). Errors are aversive-defensive motivation and the error-related negativity. Psychological Science, 19(2), 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajcak, G., McDonald, N., & Simons, R. F. (2003). Anxiety and error-related brain activity. Biological Psychology, 64(1–2), 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, G. L., Liu, Y. N., Rough, H. E., Surapaneni, M., Hanna, B. S., Arnold, P. D., & Gehring, W. J. (2020). A diagnostic biomarker for pediatric generalized anxiety disorder using the error-related negativity. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(5), 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, C. B., Dien, J., & Coles, M. G. H. (1998). Error-related scalp potentials elicited by hand and foot movements: Evidence for an output-independent error-processing system in humans. Neuroscience Letters, 242(2), 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., & Zhou, R. L. (2019). The development of test anxiety in Chinese students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(01), 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, M. F., & Rüsseler, J. (2019). Performance monitoring and correct response significance in conscientious individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V., & Corr, P. J. (1996). Menstrual cycle, arousal-induction, and intelligence test performance. Psychological Reports, 78(1), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Bai, S., Li, M., & Zhou, R. (2025). Test anxiety and trait anxiety in adolescence: Same or different structures? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 81(7), 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, S. L., Schroder, H. S., Fisher, M. E., Durbin, C. E., Fitzgerald, K. D., Danovitch, J. H., & Moser, J. S. (2017). Associations between disorder-specific symptoms of anxiety and error-monitoring brain activity in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(7), 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, C. A., Perez, V. B., Delucchi, K. L., & Mathalon, D. H. (2012). Error-related negativity in individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms: Toward an understanding of hoarding behaviors. Biological Psychology, 89(2), 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J. M., Perez-Edgar, K., Henderson, H. A., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Pine, D. S., & Fox, N. A. (2009). A History of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry, 65(5), 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. (2017). A biomarker of anxiety in children and adolescents: A review focusing on the error-related negativity (ERN) and anxiety across development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 27, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A., & Gawlowska, M. (2017). Evidence for specificity of the impact of punishment on error-related brain activity in high versus low trait anxious individuals. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 120, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A., Hajcak, G., Torpey, D. C., Kujawa, A., Kim, J., Bufferd, S., Carlson, G., & Klein, D. N. (2013). Increased error-related brain activity in six-year-old children with clinical anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A., Weinberg, A., Klein, D. N., & Hajcak, G. (2012). The development of the error-related negativity (ERN) and its relationship with anxiety: Evidence from 8 to 13 year-olds. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2(1), 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J. A., Wang, M., Kaur, M., Fitzgerald, P. B., Fitzgibbon, B. M., & Hoy, K. E. (2021). EEG correlates of attentional control in anxiety disorders: A systematic review of error-related negativity and correct-response negativity findings. Journal of Affective Disorders, 291, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, T. P., Taylor, D., & Moser, J. S. (2012). Sex moderates the relationship between worry and performance monitoring brain activity in undergraduates. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 85(2), 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J. S., Hajcak, G., & Simons, R. F. (2005). The effects of fear on performance monitoring and attentional allocation. Psychophysiology, 42(3), 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J. S., Moran, T. P., & Jendrusina, A. A. (2012). Parsing relationships between dimensions of anxiety and action monitoring brain potentials in female undergraduates. Psychophysiology, 49(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, J. S., Moran, T. P., Schroder, H. S., Donnellan, M. B., & Yeung, N. (2013). On the relationship between anxiety and error monitoring: A meta-analysis and conceptual framework. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E. (1996). No more test anxiety: Effective steps for taking tests and achieving better grades (Vol. 1). Learning Skills Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, E., & Lee, K. (2015). Effects of trait test anxiety and state anxiety on children’s working memory task performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 40, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, J. B., Heller, W., Imig, J. C., McDonald, R. P., & Miller, G. A. (2001). Distinguishing dimensions of anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvet, D. M., & Hajcak, G. (2009). The stability of error-related brain activity with increasing trials. Psychophysiology, 46(5), 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvet, D. M., & Hajcak, G. (2012). The error-related negativity relates to sadness following mood induction among individuals with high neuroticism. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(3), 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfit, G. H., Inzlicht, M., & Mennin, D. S. (2013). Anxiety and error monitoring: The importance of motivation and emotion. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., Langdale, H. C., Woods, K. A., & Nicholson, L. J. (2011). Developing and piloting a dot-probe measure of attentional bias for test anxiety. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(4), 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., Shah, J., & Lewis, R. (2014). Performance-evaluation threat does not adversely affect verbal working memory in high test-anxious persons. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 13(1), 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J. C. (1941). Standardization of progressive matrices, 1938. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 19, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesel, A., Goldhahn, S., & Kathmann, N. (2017). Hyperactive performance monitoring as a transdiagnostic marker: Results from health anxiety in comparison to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychologia, 96, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesel, A., Weinberg, A., Endrass, T., Kathmann, N., & Hajcak, G. (2012). Punishment has a lasting impact on error-related brain activity. Psychophysiology, 49(2), 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeback, R. E., Hedges-Muncy, A., Hunt, I. J., Carbine, K. A., Steffen, P. R., & Larson, M. J. (2020). The association between experimentally induced stress, performance monitoring, and response inhibition: An event-related potential (ERP) analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I. G. (1978). The test anxiety scale: Concept and research. In C. D. Spielberger, & I. G. Sarason (Eds.), Stress and Anxiety (Vol. 5, pp. 193–216). Hemisphere. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, I. G. (1984). Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference -reactions to tests. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B., & Inzlicht, M. (2020). Assessing and adjusting for publication bias in the relationship between anxiety and the error-related negativity. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 155, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, T. X. F., Benoit, E., Dempsey, C., Jennings, M., Maxwell, A., McDonough, M., & Gillan, C. M. (2020). A dimensional investigation of error-related negativity (ERN) and self-reported psychiatric symptoms. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 158, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. F. (2010). The way of our errors: Theme and variations. Psychophysiology, 47(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F., & Zhang, J. (2008). Applicability of test anxiety scale in high school students in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(06), 623–624. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. T., Chang, L., & Zhou, R. L. (2022). Effect of test anxiety on visual working memory capacity using evidence from event-related potentials. Psychophysiology, 59(2), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Yang, D., Ding, C., & Cao, M. (2018). Validity and reliability of the Short State Anxiety Inventory in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 32(10), 886–888. [Google Scholar]

- Tops, M., & Boksem, M. A. (2011). Cortisol involvement in mechanisms of behavioral inhibition. Psychophysiology, 48(5), 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, V., & Carter, C. S. (2002). The anterior cingulate as a conflict monitor: fMRI and ERP studies. Physiology & Behavior, 77(4-5), 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegler, R., Peterburs, J., Lemke, H., Ocklenburg, S., Liepelt, R., & Straube, T. (2018). Electrophysiological correlates of performance monitoring under social observation in patients with social anxiety disorder and healthy controls. Biological Psychology, 132, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., Chang, L., Huang, Q., & Zhou, R. L. (2020). Relation between spontaneous electroencephalographic theta/beta power ratio and test anxiety. Neuroscience Letters, 737, 135323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., De Beuckelaer, A., & Zhou, R. L. (2021). Enhanced or impoverished recruitment of top-down attentional control of inhibition in test anxiety. Biological Psychology, 161, 108070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., De Beuckelaer, A., & Zhou, R. L. (2022a). EEG correlates of neutral working memory training induce attentional control improvements in test anxiety. Biological Psychology, 174, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H., Oei, T. P., & Zhou, R. L. (2022b). Test anxiety impairs inhibitory control processes in a performance evaluation threat situation: Evidence from ERP. Biological Psychology, 168, 108241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H., & Sun, J. L. (2024). Examining attentional control deficits in adolescents with test anxiety: An evidential synthesis using self-report, behavioral, and resting-state EEG measures. Acta Psychologica, 246, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A., Klein, D. N., & Hajcak, G. (2012). Increased error-related brain activity distinguishes generalized anxiety disorder with and without comorbid major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(4), 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A., Meyer, A., Hale-Rude, E., Perlman, G., Kotov, R., Klein, D. N., & Hajcak, G. (2016). Error-related negativity (ERN) and sustained threat: Conceptual framework and empirical evaluation in an adolescent sample. Psychophysiology, 53(3), 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., & Wei, H. (2024). The effect of working memory training on test anxiety symptoms and attentional control in adolescents. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, N., Botvinick, M. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The neural basis of error detection: Conflict monitoring and the error-related negativity. Psychological Review, 111(4), 931–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidner, M. (1998). Test anxiety: The state of the art. Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

| LTA (N = 44) | HTA (N = 45) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (year) | 19.82 | 1.42 | 19.53 | 1.27 |

| Sex (female) | N = 23 | N = 25 | ||

| Scale checklist | ||||

| TAS | 8.57 | 2.43 | 27.49 | 3.51 |

| Pre STAS | 1.93 | 0.82 | 2.67 | 0.74 |

| Pre SSAI | 9.95 | 3.07 | 13.11 | 3.00 |

| Post STAS | 2.11 | 0.87 | 3.00 | 0.77 |

| Post SSAI | 11.73 | 3.39 | 14.91 | 3.35 |

| Behavioral data | ||||

| Pre | ||||

| Acc | 0.86 | 0.05 | 0.86 | 0.07 |

| Acc on C trials | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| Acc on IC trials | 0.77 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.10 |

| Acc after correct trials | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.06 |

| Acc after incorrect trials | 0.86 | 0.11 | 0.84 | 0.14 |

| Error RT (ms) | 389.66 | 34.94 | 389.70 | 39.29 |

| Correct RT (ms) | 441.00 | 41.80 | 443.60 | 37.37 |

| RT on C trials (ms) | 411.26 | 39.80 | 413.41 | 35.15 |

| RT on IC trials (ms) | 457.36 | 43.80 | 459.04 | 40.19 |

| Post-error slowing (ms) | 10.52 | 15.42 | 4.64 | 13.81 |

| Post | ||||

| Acc | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.04 |

| Acc on C trials | 0.96 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.02 |

| Acc on IC trials | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.76 | 0.07 |

| Acc after correct trials | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.86 | 0.04 |

| Acc after incorrect trials | 0.88 | 0.07 | 0.86 | 0.09 |

| Error RT (ms) | 371.56 | 33.54 | 373.88 | 31.26 |

| Correct RT (ms) | 415.53 | 46.19 | 417.50 | 32.34 |

| RT on C trials (ms) | 391.83 | 44.96 | 392.46 | 28.81 |

| RT on IC trials (ms) | 428.78 | 48.62 | 430.08 | 35.99 |

| Post-error slowing (ms) | 10.14 | 16.57 | 8.47 | 10.64 |

| Event-related brain potential data | ||||

| Pre | ||||

| ERN, FCz (μV) | −1.77 | 2.41 | −3.65 | 4.18 |

| CRN, FCz (μV) | 1.66 | 2.14 | 1.12 | 2.63 |

| ΔERN, FCz (μV) | −3.42 | 2.90 | −4.77 | 4.13 |

| Post | ||||

| ERN, FCz (μV) | −1.99 | 3.00 | −3.53 | 3.49 |

| CRN, FCz (μV) | 1.57 | 3.06 | 1.36 | 2.31 |

| ΔERN, FCz (μV) | −3.56 | 3.25 | −4.90 | 3.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jin, Z.; Long, F.; Wei, H. The Impact of Test Anxiety and Cognitive Stress on Error-Related Brain Activity. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010025

Jin Z, Long F, Wei H. The Impact of Test Anxiety and Cognitive Stress on Error-Related Brain Activity. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Zhenni, Fangfang Long, and Hua Wei. 2026. "The Impact of Test Anxiety and Cognitive Stress on Error-Related Brain Activity" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010025

APA StyleJin, Z., Long, F., & Wei, H. (2026). The Impact of Test Anxiety and Cognitive Stress on Error-Related Brain Activity. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010025