The Community Readiness Instrument: A Quantitative Measurement Using Statistical Best Practices to Assess Systemic Change Readiness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Community Change Readiness

1.2. Community Readiness Assessments

1.3. Community Readiness Instrument

- What is the reliability of the CRI subscale scores with a sample of university students?

- What are the psychometric properties of the CRI using a second-order confirmatory factor analysis?

- What are the psychometric properties of the CRI using Rasch analysis?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants and Recruitment Procedures

2.2. The Community Readiness Instrument

2.3. Demographics

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

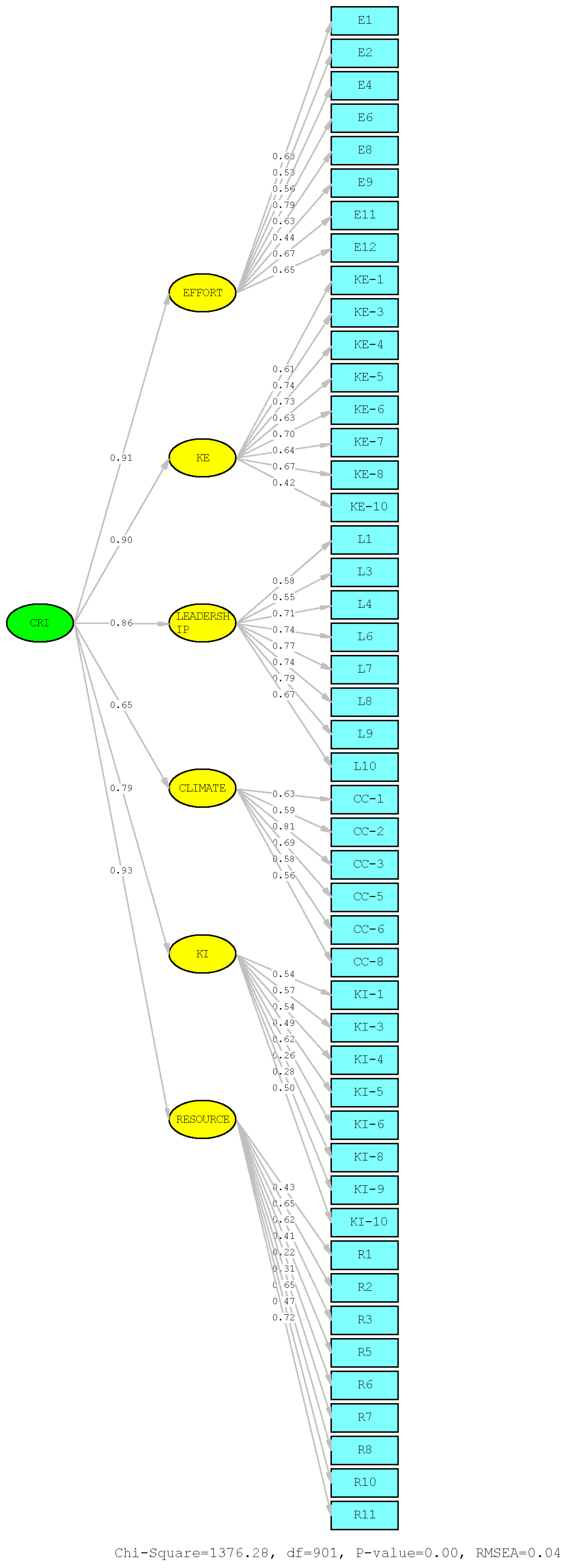

3.2. Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis Factor Loadings

3.3. Rasch Analysis

3.4. The Community Readiness Scores

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Community-Engaged Researchers

4.2. Limitations and Directions for Future CRI Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, J., Mohatt, G., Fok, C. C. T., Henry, D., & People Awakening Team. (2009). Suicide prevention as a community development process: Understanding circumpolar youth suicide prevention through community level outcomes. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 68(3), 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arambula Solomon, T. G., Jones, D., Laurila, K., Ritchey, J., Cordova-Marks, F. M., Hunter, A. U., & Villanueva, B. (2023). Using the community readiness model to assess American Indian communities readiness to address cancer prevention and control programs. Journal of Cancer Education, 38(1), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybek, E. C. (2023). The relation of item difficulty between classical test theory and item response theory: Computerized adaptive test perspective. Journal of Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 14(2), 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, T. J., Harrison, P. A., Sharma, A., & Hedger, S. (2001). The community readiness survey: Development and initial validation. Evaluation Review, 25(1), 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2015). Applying the Rasch model (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, T. G., Yan, Z., & Heene, M. (2020). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, W. J. (2016). Rasch analysis for instrument development: Why, when, and how? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), rm4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R., & Yale, M. S. (2014). Rasch analysis in the human sciences. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Veale, W. Y., Cresiski, R. H., Sharp, G., Landford, J. D., & Ugarte, F. (2025). Cultivating change: An evaluation of departmental readiness for faculty diversification. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1553580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, S. F., Holscher, J., Mumman, M. K., Salgado, H., Keir, K. B., Foster-Fishman, P. G., & Talavera, G. A. (2014). Dimensions of community and organizational readiness for change. Prog Community Health Partnership, 6(2), 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H., Fu, C.-H., Hsu, M.-H., Okoli, C., & Guo, S.-E. (2024). The effectiveness of a transtheoretical model-based smoking cessation intervention for rural smokers: A quasi-experimental longitudinal study. Patient Education and Counseling, 122, 108136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilenski, S. M., Greenberg, M. T., & Feinberg, M. E. (2007). Community readiness as a multidimensional construct. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(3), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2019). Constructing validity: New developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychological Assessment, 31(12), 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coons, S. J., Gwaltney, C. J., Hays, R. D., Lundy, J. J., Sloan, J. A., Revicki, D. A., & Lenderking, W. R. (2009). Recommendations on evidence needed to support measurement equivalence between electronic and paper-based patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures: ISPOR ePRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report. Value in Health, 12(4), 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, O., Almeida, T. C., Gonçalves, R. A., & Caridade, S. (2024). Effectiveness of the motivational interviewing techniques with perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A non-randomized clinical trial. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 33(3), 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, J. L., Clemens, E. V., Henninger, J., & Couch, C. (2020). Pre-professional suicide training for counselors: Results of a readiness assessment. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 18, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, J. L., Giegerich, V., & Ricciutti, N. M. (2022). Rurality and readiness: Addressing substance use via a community-level assessment. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 43(2), 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, J. L., Spates, K., James, T., & Lloyd, C. (2023). Readiness of a U.S. Black community to address suicide. Death Studies, 48(3), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMars, C. E. (2023). Item response theory (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale development: Theory and applications. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications (5th ed.). SACE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente, C. C., Schlundt, D., & Gemmell, L. (2004). Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. The American Journal on Addictions, 13(2), 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D. (2012). Statistical methods for validation of assessment scale data in counseling and related fields. American Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, V., & Celik, F. (2025). The 8-Factor reasoning styles scale: Development, validation, and psychometric evaluation. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K. M., Littleton, H. L., Sylaska, K. M., Crossman, A. L., & Craig, M. (2016). College campus community readiness to address intimate partner violence among LGBTQ+ young adults: A conceptual and empirical examination. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R. W., Jumper-Thurman, P., Plested, B. A., Oetting, E. R., & Swanson, L. (2000). Community readiness: Research to practice. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(3), 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effatpanah, F., Ravand, H., & Doebler, P. (2025). Differential item functioning analysis of likert scales: An overview and demonstration of rating scale tree model. Psychological Reports, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, M. A., Salheen, H. N., Almuneef, M., Saadoon, M. A., Alkhawari, M., Almindfa, A., & Almahroos, F. (2019). Child maltreatment prevention readiness in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 6(3), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhard, G. (2013). Invariant measurement: Using Rasch models in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, M. H., Reeve, B. B., Liepa, A. M., Stauffer, J. W., Hays, R. D., & Mayo/FDA Patient-Reported Outcomes Consensus Meeting Group. (2007). What is sufficient evidence for the reliability and validity of patient-reported outcome measures? Value in Health, 10(2), 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, L., Eskandari, E., Nazari, M., Karimi, M., & Khalan, Y. A. (2021). Developing strategies to improve the community readiness level to prevent drug abuse in adolescents: Based on the community readiness model, Eghlid City, Iran, 2019. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(6), 1568–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2022). Multivariate data analysis (9th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, R. K., Swaminathan, H., & Rogers, H. J. (1991). Fundamental of item response theory. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, E., Sanon, V., Mast, D. K., Kibbe, D., & Lyn, R. (2020). Increasing community readiness for childhood obesity prevention: A case study of four communities in Georgia. Health Promotion Practice, 22(5), 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D. (2019). Development of a quantitative measure of community readiness for change. Health and Nutritional Sciences Graduate Students Plan B Capstone Projects, 3, 13. Available online: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/hns_plan-b/3 (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Hunter, H. (2024). The transtheoretical model of behavior change: Implications for social work practice. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 34(2), 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T., Spates, K., Cureton, J. L., Patel, S., Lloyd, C., & Daniel, D. (2022). “Is this really our problem?”: A qualitative exploration of Black Americans’ misconceptions about suicide. Deviant Behavior, 44(2), 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl, M., Brew-Sam, N., Strobl, H., Tittlebach, S., & Loss, J. (2021). Evaluation of community readiness for change prior to a participatory physical activity intervention in Germany. Health Promotion International, 36(2), ii40–ii52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, A., Fatupaito, B., & Witzel, M. (2018). Is culturally based prevention effective? Results from a 3-year tribal substance use prevention program. Evaluation and Program Planning, 71, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, P., Ngo, C. L., Bragge, P., & Tsering, D. (2023). Adapting community readiness assessments for use with justice-related interventions: A rapid review. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/3325639/MSDI_PRF_Rapid-Review-4_Community-Readiness_final_22Jun23.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Kesten, J. M., Griffiths, P. L., & Cameron, N. (2015). A critical discussion of the community readiness model using a case study of childhood obesity prevention in England. Health and Social Care in the Community, 23(3), 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinov, I., Daniel, M., Stanley, L., Gancia, A., & Cargo, M. (2015). A systematic review of community readiness tool applications: Implications for reporting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12, 3453–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J. M. (2002). What do infit, outfit, mean-square, and standardization mean? Archives of Rasch Measurement, 16, 871–882. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J. M. (2024). FACETS Rasch measurement computer program (Version 4.7.5) [Computer software]. Winsteps.com. Available online: https://www.winsteps.com/facets.htm (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- López-Pina, J.-A., & Veas, A. (2024). Validation of psychometric instruments with classical test theory in social and health sciences: A practical guide. Anales de Psicología, 40(1), 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakshina, J., Mironets, S., Pavlova, A., Ismatullina, V., Lobaskova, M. M., Pecherkina, A. A., Symaniuk, E. E., & Malykh, S. B. (2025). Psychometric properties of the Brief COPE inventory on a student sample. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnaughy, E. A., Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1983). Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychotherapy: Theory Research and Practice, 20(3), 368–375. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, T., Travers, Á., Cunningham, T., Armour, C., & Hansen, M. (2023). Readiness to change and deception as predictors of program completion in perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 40(6), 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Mikton, C., Power, M., Raleva, M., Makoae, M., Eissa, M. A., Cheah, I., Cardia, N., Choo, C., & Almuneef, M. (2013). The assessment of the readiness of five countries to implement child maltreatment prevention programs on a large scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2023). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change and grow. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. R., & Tonigan, J. S. (1996). Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellmann, S., Brand, T., Jurgens, D., Gansefort, D., & Zeeb, J. (2021). How many key informants are enough? Analysing the validity of the community readiness assessment. BMC Research Notes, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health [NIH]. (2011). Principles of community engagement (2nd ed.). National Institute of Health. Available online: https://crs.od.nih.gov/CRSPublic/View.aspx?Id=1139 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Nhassengo, S., Laflamme, L., & Sengoelge, M. (2025). Community readiness to prevent child maltreatment in Mozambique: An investigation among national and local key informants. Injury Prevention, 30(1), 108400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, M., Omidvar, N., Amiri, P., & Eini-Zinab, H. (2023). Adapting the community readiness model and validating a community readiness tool for childhood obesity prevention programs in Iran. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, 56(1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, M. R. (1966). The axioms and principal results of classical test theory. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 3(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetting, E. R., Donnermeyer, J. F., Plested, Barbara, A., Edwards, R. W., Kelly, K., & Beauvais, F. (1995). Assessing community readiness for prevention. The International Journal of the Addictions, 30(6), 659–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J., Parikh-Foxx, S., & Flowers, C. (2020). A confirmatory factor analysis of the school counselor knowledge and skills survey for multi-tiered systems of support. The Professional Counselor, 10(3), 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plested, B. A., Jumper-Thurman, P., & Edwards, R. W. (2016). Community readiness manual. National Center for Community and Organizational Readiness, Colorado State University. Available online: https://nccr.colostate.edu/ (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Prieto, G., & Delgado, A. R. (2010). Reliability and validity. Papers on Psychology, 31(1), 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 19(3), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciutti, N. M., Zhang, S., & Cureton, J. L. (2026). Differential item functioning for the community readiness instrument: Detecting differences in change readiness across community subgroups (Report in preparation). University of North Carolina Charlotte. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas, S. R., Behar, L. B., & Hydaker, W. M. (2016). Community readiness within systems of care: The validity and reliability of the System of Care Readiness and Implementation Measurement Scale (SOCRIMS). The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 43(1), 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M., Schnabel, M., Holger, H., & Babitsch, B. (2022). Application of the community readiness model for childhood obesity prevention: A scoping review. Health Promotion International, 37(4), daac120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, Y., Wahl, Y., Glatt, S., Levin, C., Tran, P., & Goodman, M. (2024). The transtheoretical model of change and recovery from a suicidal episode. Archives of Suicide Research, 29(3), 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standerfer, C., Loker, E., & Lochmann, J. (2022). Look before you leap: Assessing community readiness for action on science and health policy issues. JCOM, 21(2), N03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C. B., & Dahir, C. A. (2015). School counselor evaluation instrument pilot project: A school counselor association, department of education, and university collaboration. Journal of School Counseling, 13(12), n12. Available online: https://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v13n12.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]: Mid-America Prevention Technology Transfer Center. (2022a). Community engagement process. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/tribal-ttac/training-technical-assistance/community-engagement-process (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]: Mid-America Prevention Technology Transfer Center. (2022b). The guide to the eight professional competencies for higher education substance misuse prevention (Professional Competencies Guide). Available online: https://pttcnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Prevention-Professionals-Competencies-Initiative-Final-October2022.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Swan, S. A., & Allan, E. J. (2023). Assessing readiness for campus hazing prevention. Health Education & Behavior, 50(5), 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research [TEC]. (2014). Community readiness for community change (2nd ed.). Colorado State University. [Google Scholar]

- Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research [TEC]. (2025). Tri-ethnic center for prevention research. Available online: https://tec.colostate.edu/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Van Zanden, B., & Bliokas, V. (2022). Taking the next step: A qualitative study examining processes of change in a suicide prevention program incorporating peer-workers. Psychological Services, 19(3), 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, J. E., Cook, E. J., Ali, N., Wilkinson, E., & Randhawa, G. (2024). Community readiness to address disparities in access to cancer, palliative and end-of-life care for ethnic minorities. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijters, B., & Baumgartner, H. (2012). Misresponse to reversed and negated items in surveys: A review. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(5), 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. J., Amick, H., & Lee, S.-Y. D. (2008). Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: A review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Medical Care Research and Review, 65(4), 379–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R., Abo-Hilal, M., Steel, Z., Hunt, C., Plested, B., Hassan, M., & Lawsin, C. (2020). Community readiness in the Syrian refugee community in Jordan: A rapid ecological assessment tool to build psychosocial service capacity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(2), 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R. F., Braun, J. M., & Kopylev, L. (2022). Principles for evaluating psychometric tests. In NEIHS report on evaluating features and application of neurodevelopmental tests in epidemiological studies. National Institute of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, H., Kyröläinen, A., & Kuperman, V. (2022). How representative are student convenience samples? A study of literacy and numeracy skills in 32 countries. PLoS ONE, 17(7), E0271191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2013). Handbook for the Readiness Assessment for the Prevention of Child Maltreatment (RAP-CM). Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/child-maltreatment/rap-cm-handbook.pdf?sfvrsn=9282691e_2 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2020). Readiness assessment for the prevention of child maltreatment (RAP-CM). Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/readiness-assessment-for-the-prevention-of-child-maltreatment-(rap-cm) (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2021). 10 steps to community readiness: What countries should do to prepare communities for a COVID-19 vaccine, treatment or new test. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-2019-nCoV-Community_Readiness-2021.1 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Yoshihama, M., & Hammock, A. C. (2023). Assessing community readiness to develop a socioculturally relevant intimate partner violence prevention program. Prevention Science, 24, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Dai, B., & Lin, L. (2023). Validation of a Chinese version of the digital stress scale and development of a short form based on item response theory among Chinese college students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 2897–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S., Ricciutti, N. M., & Cureton, J. L. (2025). The community readiness instrument: Counselors’ opportunity to advocate for community changes to substance use trends. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 58(3), 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurawel, J. A., Lacasse, K., Spas, J. J., & Merrill, J. E. (2024). Identifying the trajectory of public stigma across the stages of recovery from a substance use disorder. Stigma and Health, 9(4), 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tools | Attributes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFA | CFA | Rasch | Expert Review | TTM | CRM | SUD | Issue Adapt. | |

| CRA (Plested et al., 2016) | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| CCRS (Hicks, 2019) | X | X | X | |||||

| RAP-CM (Mikton et al., 2013) | X | |||||||

| RAP-CM Short Version (WHO, 2013) | X | |||||||

| SOC-RIMS (Rosas et al., 2016) | X | X | ||||||

| CRS (Beebe et al., 2001) | X | X | X | X | ||||

| CRI (S. Zhang et al., 2025) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Items | M | SD | Measure | Infit | Outfit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-1. The community members view the current effort(s) to address substance use as widely successful. | 2.44 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| E-2. The effort(s) in the community to address student substance use have existed for a long time (i.e., 4 or more years). | 2.82 | 0.68 | −0.72 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| E-4. The effort(s) in the community to address student substance use serve a broad range of students (i.e., racial/ethnic, sexual orientation, first-generation students, veteran students, etc., groups). | 2.84 | 0.75 | −0.80 | 1.27 | 1.26 |

| E-6. There are many efforts in the community to address student substance use | 2.45 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| E-8. There are many in the community (e.g., individuals, university offices and departments) who are trying to get something started to address student substance use. | 2.58 | 0.68 | 0.17 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| E-9. Most community members see a need for efforts to address student substance use. | 2.77 | 0.67 | −0.52 | 1.23 | 1.23 |

| E-11. Meetings have been held in the community (e.g., student groups, departments, or university offices) to discuss the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.62 | 0.68 | 0.08 | 0.85 | 0.83 |

| E-12. Evaluations valuation plans are used to test the effectiveness of the community effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.50 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| KE-1. The community members have accurate information about the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.44 | 0.70 | −0.07 | 1.15 | 1.11 |

| KE-3. The community members have heard of the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.58 | 0.73 | −0.53 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| KE-4. The community members can name the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.17 | 0.77 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| KE-5. The community members have basic knowledge about the effort(s) to address student substance use. (Basic knowledge might include knowing the purpose of the efforts or who the efforts are for.) | 2.70 | 0.67 | −1.17 | 0.98 | 0.93 |

| KE-6. The community members have specific knowledge about the effort(s). (Specific knowledge might include when and where the efforts occur, how they are implemented, etc.). | 2.16 | 0.73 | 1.12 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| KE-7. The community members know how well (or not well) the effort(s) to address student substance use are working. | 2.19 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| KE-8. The community members are aware of the strengths/benefits of the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.64 | 0.72 | −0.84 | 1.13 | 1.10 |

| KE-10. The community members are aware of the weaknesses/limitations of the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.58 | 0.66 | −0.49 | 1.22 | 1.23 |

| L-1. The community leaders view student substance use as a major concern. | 2.72 | 0.77 | −0.26 | 1.51 | 1.43 |

| L-3. The community leaders believe student substance use is a problem | 2.91 | 0.64 | −1.25 | 1.16 | 1.18 |

| L-4. The community leaders view addressing the issue of student substance use as a major priority. | 2.44 | 0.73 | 1.20 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| L-6. The community leaders actively support the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.78 | 0.61 | −0.55 | 0.82 | 0.79 |

| L-7. The community leaders have participated in developing, improving, or implementing the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.66 | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.76 | 0.72 |

| L-8. The community leaders are seeking or allocating resources to fund efforts to address student substance use. | 2.53 | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| L-9. The community leaders are driving initiatives to improve/expand the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.54 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.74 |

| L-10. The community leaders support the development of new efforts to address the issue of student substance use. | 2.83 | 0.58 | −0.81 | 0.94 | 0.90 |

| CC-1. The community members believe that student substance use is a concern. | 2.87 | 0.61 | −0.61 | 0.82 | 0.80 |

| CC-2. The community members believe the issue of student substance use should be addressed. | 2.97 | 0.57 | −1.17 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| CC-3. Addressing the issue of student substance use is a priority to the community members. | 2.58 | 0.70 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| CC-5. The community members actively support the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.75 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 1.06 | 1.09 |

| CC-6. The community members support expanding the existing effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.81 | 0.57 | −0.25 | 0.96 | 1.07 |

| CC-8. The community members seem troubled by student substance use. | 2.58 | 0.70 | 0.97 | 1.19 | 1.26 |

| KI-1. Members of the community have access to information regarding student substance use. | 2.66 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 1.24 | 1.25 |

| KI-3. Members of the community have basic knowledge about student substance use (e.g., signs and symptoms that someone is using). | 2.91 | 0.61 | −0.24 | 0.77 | 0.73 |

| KI-4. The community members have specific knowledge about student substance use (why students use, how many/often students use, impacts of and treatments for using, etc.). | 2.32 | 0.71 | 1.88 | 1.14 | 1.21 |

| KI-5. The community members know the harmful effects of student substance use. | 3.07 | 0.57 | −0.87 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| KI-6. The community members have accurate information about student substance use. | 2.41 | 0.67 | 1.61 | 0.86 | 0.89 |

| KI-8. The community members know that student substance use occurs on campus. | 3.18 | 0.65 | −1.31 | 1.20 | 1.26 |

| KI-9. The community members recognize that some students may be using substances. | 3.21 | 0.59 | −1.48 | 1.00 | 1.07 |

| KI-10. The community members consider student substance use to be worth knowing about. | 2.93 | 0.59 | −0.29 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| R-1. There are many resources in the community that could be used to address student substance use (even if they are not currently used for that issue). | 2.69 | 0.72 | −0.48 | 1.26 | 1.23 |

| R-2. The existing effort(s) to address student substance use in the community are adequately funded. | 2.34 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| R-3. Substantial financial resources (e.g., budgets, donations, grants, etc.) are available to members of the community to address student substance use. | 2.21 | 0.66 | 1.24 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| R-5. There is plenty of time available to the community (e.g., to plan and implement efforts) to address student substance use. | 2.63 | 0.70 | −0.24 | 1.12 | 1.08 |

| R-6. There are plenty of places/locations available in the community to host efforts to address student substance use. | 2.92 | 0.64 | −1.34 | 1.11 | 1.06 |

| R-7. There are plenty of people available to the community (e.g., to coordinate or volunteer for efforts) to address student substance use. | 2.81 | 0.65 | −0.88 | 1.04 | 1.00 |

| R-8. Many experts on student substance use are invited to campus to inform the community about the issue. | 2.19 | 0.69 | 1.35 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| R-10. Members of the community support using available resources for the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.86 | 0.57 | −1.11 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| R-11. There are numerous initiatives by the community to seek additional resources (e.g., money, time, space, people) for the effort(s) to address student substance use. | 2.37 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ricciutti, N.M.; Cureton, J.L.; Zhang, S. The Community Readiness Instrument: A Quantitative Measurement Using Statistical Best Practices to Assess Systemic Change Readiness. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010153

Ricciutti NM, Cureton JL, Zhang S. The Community Readiness Instrument: A Quantitative Measurement Using Statistical Best Practices to Assess Systemic Change Readiness. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicciutti, Natalie M., Jenny L. Cureton, and Sijia Zhang. 2026. "The Community Readiness Instrument: A Quantitative Measurement Using Statistical Best Practices to Assess Systemic Change Readiness" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010153

APA StyleRicciutti, N. M., Cureton, J. L., & Zhang, S. (2026). The Community Readiness Instrument: A Quantitative Measurement Using Statistical Best Practices to Assess Systemic Change Readiness. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010153