Exploring Attachment-Related Factors and Psychopathic Traits: A Systematic Review Focused on Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Psychopathy in Women: An Overview

3. Attachment: A Perspective of Theory from Childhood to Adulthood

4. Attachment, Psychopathy, and the Need for Gender-Sensitive Approaches

5. Attachment-Related Factors and Psychopathy: Maternal and Paternal Influences

6. Current Study

7. Methods

8. Eligibility Criteria

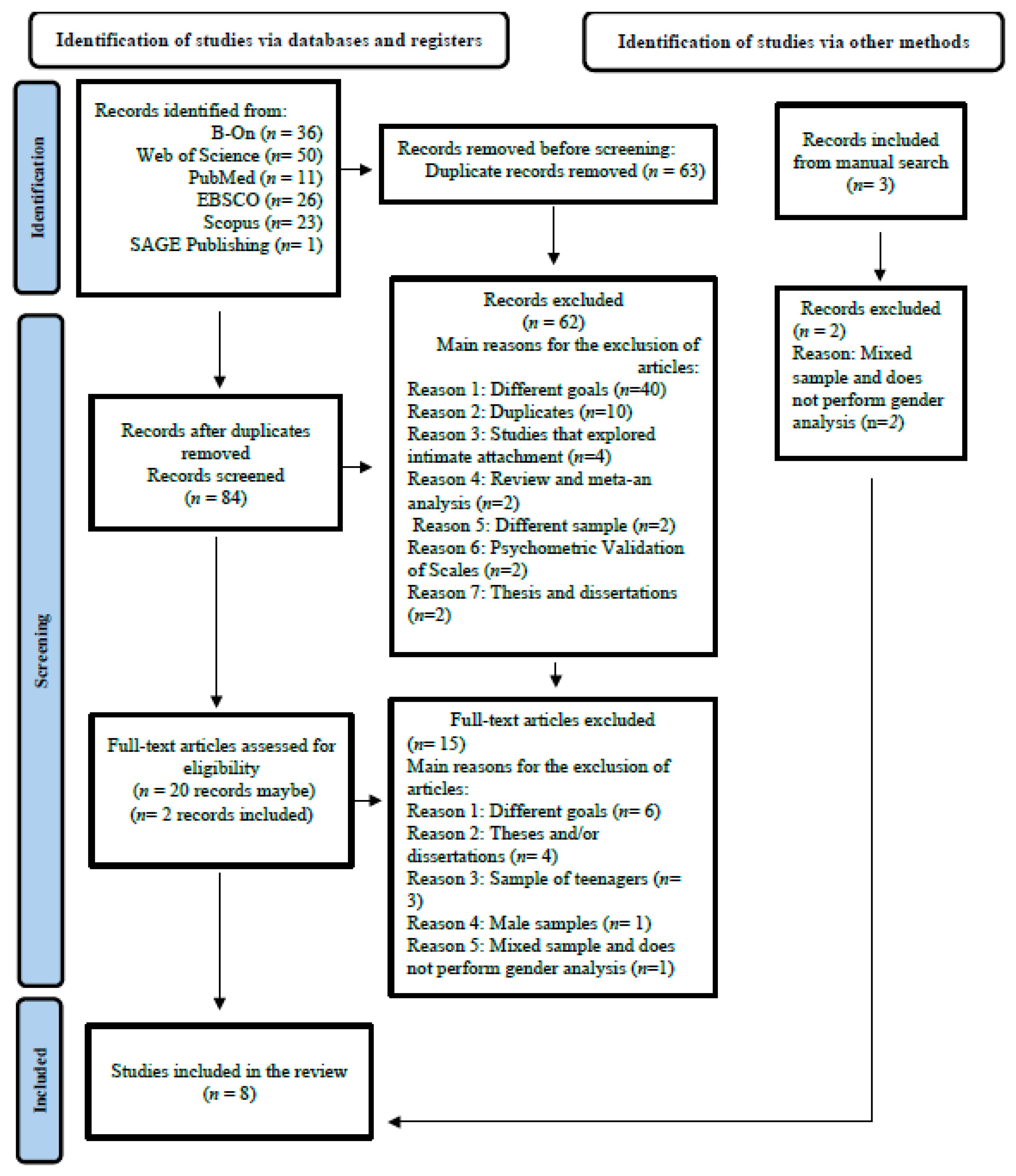

9. Search Strategies

10. Study Selection

11. Data Extraction

12. Methodological Quality Analysis

13. Results

14. Included Studies

15. Quality Assessment

16. Characteristics of Studies Included

Sample Characteristics

17. Main Outcomes

17.1. Attachment Styles and Psychopathy

17.2. Early Life Experiences, Attachment-Related Factors, and Psychopathy

18. Discussion

19. Conclusions: Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Amir-Behghadami, M., & Janati, A. (2020). Population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study (PICOS) design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in systematic reviews. Emergency Medicine Journal: EMJ, 37(6), 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Arrigo, B. A., & Griffin, A. (2004). Serial murder and the case of Aileen Wuornos: Attachment theory, psychopathy, and predatory aggression. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(3), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, K. M., Barnes, J. C., May, J. S., & Schwartz, J. A. (2011). Psychopathic personality traits, genetic risk, and gene-environment correlations. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(9), 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisby, M. A., Kimonis, E. R., & Goulter, N. (2017). Low maternal warmth mediates the relationship between emotional neglect and callous-unemotional traits among male juvenile offenders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 1790–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, B. L., Perry, N. B., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & Shanahan, L. (2014). The indirect effects of maternal emotion socialization on friendship quality in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, R. J. (2007). The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(9), 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Bloxsom, C. A., Firth, J., Kibowski, F., Egan, V., Sumich, A. L., & Heym, N. (2021). Dark shadow of the self: How the dark triad and empathy impact parental and intimate adult attachment relationships in women. Forensic Science International: Mind and Law, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Britto, P. R., Lye, S. J., Proulx, K., Yousafzai, A. K., Matthews, S. G., Vaivada, T., Perez-Escamilla, R., Rao, N., Ip, P., Fernald, L. C. H., MacMillan, H., Hanson, M., Wachs, T. D., Yao, H., Yoshikawa, H., Cerezo, A., Leckman, J. F., Bhutta, Z. A., & Early Childhood Development Interventions Review Group, for the Lancet Early Childhood Development Series Steering Committee. (2017). Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. L., Mangelsdorf, S. C., & Neff, C. (2012). Father involvement, paternal sensitivity, and father-child attachment security in the first 3 years. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 26(3), 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla, M. A., & Kosson, D. S. (2016). Psychopathic traits moderate relationships between parental warmth and adolescent antisocial and other high-risk behaviors. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(6), 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, E., Sellbom, M., & Wilkinson, R. B. (2017). Clarifying the associations between individual differences in general attachment styles and psychopathy. Personality Disorders, 8(4), 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 644–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covington, S. S. (2007). Women and the criminal justice system. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 17(4), 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, J. A. (2021). Measuring the security of attachment in adults: Narrative assessments and self-report questionnaires. In R. A. Thompson, J. A. Simpson, & L. J. Berlin (Eds.), Attachment: The fundamental questions (pp. 86–92). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Dawel, A., O’Kearney, R., McKone, E., & Palermo, R. (2012). Not just fear and sadness: Meta-analytic evidence of pervasive emotion recognition deficits for facial and vocal expressions in psychopathy. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(10), 2288–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J., Chen, C., Harenski, C., & Kiehl, K. A. (2013). An fMRI study of affective perspective taking in individuals with psychopathy: Imagining another in pain does not evoke empathy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gaizo, A. L., & Falkenbach, D. M. (2008). Primary and secondary psychopathic-traits and their relationship to perception and experience of emotion. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M. (2009). Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(1), 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delk, L. A., Bobadilla, L., & Lima, E. N. (2017). Psychopathic traits associate differentially to anger, disgust and fear recognition among men and women. Journal of Psychopathology Behavioral Assessment, 39, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, G., Russon, J., & Levy, S. (2016). Attachment-based family therapy: A review of the empirical support. Family Process, 55(3), 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giacomo, E., Santorelli, M., Pessina, R., Rucco, D., Placenti, V., Aliberti, F., Colmegna, F., & Clerici, M. (2021). Child abuse and psychopathy: Interplay, gender differences and biological correlates. World Journal of Psychiatry, 11(12), 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Doroszczyk, M., & Talarowska, M. E. (2023). Young’s early maladaptive schemas versus psychopathic traits in a non-clinical population. Postepy Psychiatrii Neurologii, 32(2), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, M., Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Albus, K. E. (2008). Attachment and psychopathology in adulthood. In J. Cassidy, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 718–744). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duschinsky, R. (2020). Cornerstones of attachment research. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschinsky, R., Bakkum, L., Mannes, J. M. M., Skinner, G. C. M., Turner, M., Mann, A., Coughlan, B., Reijman, S., Foster, S., & Beckwith, H. (2021). Six attachment discourses: Convergence, divergence and relay. Attachment & Human Development, 23(4), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, H., Alpers, G. W., Segrè, D., Calogero, A., & Angrilli, A. (2008). Categorization and evaluation of emotional faces in psychopathic women. Psychiatry Research, 159(1–2), 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Eisenbarth, H., Krammer, S., Edwards, B. G., Kiehl, K. A., & Neumann, C. (2018). Structural analysis of the PCL-R and relationship to BIG FIVE personality traits and parenting characteristics in an Hispanic female offender sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 129, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkenbach, D. M., Reinhard, E. E., & Larson, F. R. R. (2017). Theory based gender differences in psychopathy subtypes. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D. P. (2007). Social origins of psychopathy. In A. R. Felthous, & H. Saβ (Eds.), International handbook on psychopathic disorders and the law (pp. 319–334). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- *Farrington, D. P., & Bergstrøm, H. (2023). Explanatory risk factors for psychopathic symptoms in men and women: Results from generation 3 of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Development Life-Course Criminology, 9, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E. L., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. Other Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzan, E., & Cooke, D. J. (2005). Figuring out la femme fatale: Conceptual and assessment issues concerning psychopathy in females. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 23(6), 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R. C. (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-Analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(2), 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R. C., & Dugan, K. A. (2021). The consistency of attachment security across time and relationships. In R. A. Thompson, J. A. Simpson, & L. J. Berlin (Eds.), Attachment: The fundamental questions (pp. 147–153). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, B., Caridade, C., & Cunha, O. (2024). Intervention with female perpetrators of sexual crimes: A practical case. In Psychological intervention with adults (pp. 205–220). S. Caridade, & C. Fonte (Coords.). Pactor. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, P. J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Kahn, R. E. (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaik, L. P., Abdullah, M. C., Elias, H., & Uli, J. (2010). Development of antisocial behaviour. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Raine, A., Venables, P. H., Dawson, M. E., & Mednick, S. A. (2010). Association of poor childhood fear conditioning and adult crime. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, J. P., Knight, R. A., Ruscio, J., & Hare, R. D. (2018). A taxometric investigation of psychopathy in women. Psychiatry Research, 261, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C. E. (2000). Continuity and discontinuity of attachment from infancy through adolescence. Child Development, 71, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, R. D. (2003). Manual for the revised psychopathy checklist (2nd ed.). Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawes, D. J., Dadds, M. R., Frost, A. D., & Hasking, P. A. (2011). Do childhood callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 40(4), 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, B. M., Vaidyanathan, U., & Patrick, C. J. (2010). Validating female psychopathy subtypes: Differences in personality, antisocial and violent behavior, substance abuse, trauma, and mental health. Personality Disorders, 1(1), 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2017). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In J. P. T. Higgins, R. Churchill, J. Chandler, & M. S. Cumpston (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.2.0, updated June 2017). Cochrane. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/sites/training.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/resources/Handbook5_1/Chapter_8_Handbook_5_2_8.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Hong, H. G., Kim, H., Han, J., & Lee, J. (2016). Impact of parental abuse during childhood on the formation of primary and secondary psychopathy. Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35(3), 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fabregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. (Registration of Copyright (#1148552)). Industry Canada: Canadian Intellectual Property Office. [Google Scholar]

- Karpman, B. (1941). On the need of separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types: The symptomatic and the idiopathic. Journal of Criminal Psychopathology, 3, 112–137. [Google Scholar]

- Killeen, T. K., & Brewerton, T. D. (2023). Women with PTSD and substance use disorders in a research treatment study: A comparison of those with and without the dissociative subtype of PTSD. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation: The Official Journal of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation (ISSD), 24(2), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein Haneveld, E., Molenaar, D., de Vogel, V., Smid, W., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2022). Do we hold males and females to the same standard? A measurement invariance study on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Journal of Personality Assessment, 104(3), 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobak, R., & Madsen, S. (2008). Disruptions in attachment bonds: Implications for theory, research, and clinical intervention. In J. Cassidy, & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 23–47). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Kyranides, M. N., Kokkinou, A., Imran, S., & Cetin, M. (2023). Adult attachment and psychopathic traits: Investigating the role of gender, maternal and paternal factors. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 42(6), 4672–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Kyranides, M. N., & Neofytou, L. (2021). Primary and secondary psychopathic traits: The role of attachment and cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M., Feiring, C., & Rosenthal, S. (2000). Attachment over time. Child Development, 71(3), 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons-Ruth, K., & Jacobvitz, D. (2016). Attachment disorganization from infancy to adulthood: Neurobiological correlates, parenting contexts, and pathways to disorder. Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 3, 667–695. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, S., Brumariu, L. E., Villani, V., Atkinson, L., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2016). Representational and questionnaire measures of attachment: A meta-analysis of relations to child internalizing and externalizing problems. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 367–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marganska, A., Gallagher, M., & Miranda, R. (2013). Adult attachment, emotion dysregulation, and symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(1), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M. P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R., Dodson, M. C., Rosenfield, D., & Jouriles, E. N. (2011). Effects of a parenting intervention on features of psychopathy in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(7), 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2012). An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 11(1), 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2019). Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Watts, A., & Jones, S. E. (2011). Does psychopathy manifest divergent relations with components of its nomological network depending on gender? Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5), 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffett, S., Javdani, S., Miglin, R., & Sadeh, N. (2020). Examining latent profiles of psychopathy in a mixed-gender sample of juvenile detainees. Personality Disorders, 11(4), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, R., Ireland, J. L., & Lewis, M. (2019). Understanding interpersonal relationships and psychopathy. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 30(4), 658–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, C. B., & Pilkington, P. D. (2020). Intimate partner violence and child attachment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 109, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, C. J. (1994). Emotion and psychopathy: Startling new insights. Psychophysiology, 31(4), 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, C. J. (2010). Operationalizing the triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Preliminary description of brief scales for assessment of boldness, meanness, and disinhibition (pp. 1110–1131). (Unpublished test manual). Florida State University. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, M., Gonçalves, R. A., & Cunha, O. (2022). Psychopathy and reoffending among incarcerated women. Women & Criminal Justice, 32(6), 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M., Gonçalves, R. A., & Cunha, O. (2023). Emotional processing and psychopathy among women: A systematic review. Deviant Behavior, 45(10), 1366–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raby, K. L., Steele, R. D., Carlson, E. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (2015). Continuities and changes in infant attachment patterns across two generations. Attachment & Human Development, 17(4), 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A., Lencz, T., Taylor, K., Hellige, J. B., Bihrle, S., Lacasse, L., Lee, M., Ishikawa, S., & Colletti, P. (2003). Corpus callosum abnormalities in psychopathic antisocial individuals. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(11), 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H. T., Collins, W. A., & Berscheid, E. (2000). The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 844–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, S. J., Power, H. A., & Wright, K. D. (2019). Examining the relationships between childhood abuse history, attachment, and health anxiety. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(7), 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, T. D., & King, A. R. (2016). Anxious, hostile, and sadistic: Maternal attachment and everyday sadism predict hostile masculine beliefs and male sexual violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekin, R. T., Rogers, R., Ustad, K. L., & Sewell, K. W. (1998). Psychopathy and recidivism among female inmates. Law and Human Behavior, 22, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkadi, A., Kristiansson, R., Oberklaid, F., & Bremberg, S. (2008). Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatrica, 97(2), 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., Pace, U., Manzella, S., Di Carlo, G., & Caretti, V. (2014). The relationship between attachment and psychopathy: A study with a sample of violent offenders. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 33(3), 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuengel, C., Verhage, M. L., & Duschinsky, R. (2021). Prospecting the attachment research field: A move to the level of engagement. Attachment & Human Development, 23(4), 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seara-Cardoso, A., Queirós, A., Fernandes, E., Coutinho, J., & Neumann, C. (2019). Psychometric properties and construct validity of the short version of the self-report psychopathy scale in a southern European sample. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(4), 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2002). Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment & Human Development, 4(2), 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, V., Moss, E., & Pascuzzo, K. (2011). Early maladaptive schemas and child and adult attachment: A 15-year longitudinal study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(4), 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeem, J. L., Poythress, N., Edens, J. F., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Cale, E. M. (2003). Psychopathic personality or personalities? Exploring potential variants of psychopathy and their implications for risk assessment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 8(5), 513–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H., & Steele, M. (2021). Categorical assessments of attachment: On the ontological relevance of group membership. In R. A. Thompson, J. A. Simpson, & L. J. Berlin (Eds.), Attachment: The fundamental questions (pp. 63–69). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. A., Simpson, J. A., & Berlin, L. J. (2022). Taking perspective on attachment theory and research: Nine fundamental questions. Attachment & Human Development, 24(5), 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, J., Koskuvi, M., Lähteenvuo, M., Virtanen, P. L. J., Ojansuu, I., Vaurio, O., Gao, Y., Hyötyläinen, I., Puttonen, K. A., Repo-Tiihonen, E., Paunio, T., Rautiainen, M. R., Tyni, S., Koistinaho, J., & Lehtonen, Š. (2020). Neurobiological roots of psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(12), 3432–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Voorhis, P., Wright, E. M., Salisbury, E., & Bauman, A. (2010). Women’s risk factors and their contributions to existing risk/needs assessment: The current status of a gender-responsive supplement. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(3), 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P., D’Aguanno, M., de Campora, G., Di Francescantonio, S., Garofalo, C., Giromini, L., Petrocchi, C., Terrasi, M., & Zavattini, G. C. (2015). Gender moderates the relationship between attachment insecurities and emotion dysregulation. South African Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M. P., Oosterman, M., Cassibba, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: A synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 142(4), 337–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verona, E., & Vitale, J. (2006). Psychopathy in women. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy. [Google Scholar]

- Verona, E., & Vitale, J. (2018). Psychopathy in women: Assessment, manifestations, and etiology. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (2nd ed., pp. 509–528). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, J. E., Brinkley, C. A., Hiatt, K. D., & Newman, J. P. (2007). Abnormal selective attention in psychopathic female offenders. Neuropsychology, 21(3), 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Walsh, H. C., Roy, S., Lasslett, H. E., & Neumann, C. S. (2019). Differences and similarities in how psychopathic traits predict attachment insecurity in females and males. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41(4), 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71(3), 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, R., Høiseth, M. H., & Pettersen, G. (2012). Psychopathy in women: Theoretical and clinical perspectives. International Journal of Women’s Health, 4, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Variable(s)| Objective(s) | Measures | Main Outcomes | Key Themes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment | Psychopathy | ||||

| Arrigo and Griffin (2004) | Examine attachment theory, psychopathy and predatory homicide relationship | Books, taped interviews, television programs, and newspaper articles, chronicling the life events of Aileen Wuornos | Aillen’s Childhood:

| Early Life Experiences, Attachment Styles, and Psychopathy | |

| Bloxsom et al. (2021) | Investigate the interrelationships of the Dark Triad and its unique trait associations with parental and intimate adult (best friend/partner) attachment difficulties, along with the mediating role of empathic deficits. | Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R): anxiety attachment and avoidant attachment | Dark Triad of Personality—Short Version (Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and Psychopathy) | Anxious and avoidant parental attachment positively correlated with psychopathy; avoidant parental attachment also correlated with Machiavellianism. Machiavellianism and psychopathy positively correlated with anxious and avoidant adult attachment to best friends/partners. Cognitive and affective empathy negatively correlated with avoidant attachment and positively with anxious attachment in best friend relationships. Insecure parental attachment predicts psychopathy and Machiavellianism, though weakly. Psychopathy is directly and indirectly linked to insecure adult intimate attachments. Women with avoidant parental attachment are more likely to exhibit Machiavellian and psychopathic traits, influencing adult intimate relationships. | Attachment Styles and Psychopathy |

| Doroszczyk and Talarowska (2023) | Examine the relationship between Young’s early maladaptive schemas and psychopathic personality traits in a non-clinical population. | Young’s Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-S3-PL) | Psychopathic Personality Traits Scale—Revised (PPTS-R) (Affective Responsiveness, Cognitive Responsiveness, Interpersonal Manipulation, and Egocentricity) Triarchic Psychopathy Measure (TriPM) (Boldness, Meanness, and Disinhibition) | Correlations between psychopathy severity and early maladaptive schemas:

| Early Life Experiences, Attachment-related Factors, and Psychopathy |

| Eisenbarth et al. (2018) | Investigating the factor structure and construct validity of the PCL-R in a Hispanic female sample | Measure of Parenting Style (MOPS) | Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R) (Interpersonal, Affective, Lifestyle, and Antisocial factors) NEO-PI Five-Factor Inventory (FFI) (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism) | Indifference and abusive parenting styles are positively associated with higher psychopathic traits. Abusive maternal style is significantly linked to the lifestyle facet of psychopathy. Psychopathic traits correlate strongly with both maternal and paternal parenting styles. Maternal styles have a stronger direct effect on psychopathy than paternal styles. The influence of parenting styles on psychopathy is partly mediated by the Five Factor Model (FFM). | Early Life Experiences, Attachment-related Factors, and Psychopathy |

| Farrington and Bergstrøm (2023) | Identify the main risk factors for psychopathy in men and women. Compare the differences in risk factors for psychopathy between men and women. Determine which risk factors are independently predictive of psychopathy in men and women. | Parental Attitude Schedules developed: retrospective questions about their childhood | Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV) (F1-PP Factor 1, psychopathic personality; F2-PB Factor 2, psychopathic behaviour) | Relationship between psychopathy and convictions:

| Early Life Experiences, Attachment-related Factors, and Psychopathy |

| Kyranides and Neofytou (2021) | Explore the relationship between adult insecure attachment dimensions and CERQ with both primary and secondary traits | Relationship Scale Questionnaire (RSQ): measure adult attachment in terms of general orientations to close and interpersonal relationships (anxiety and avoidance attachment) | Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP) (Primary and Secondary Psychopathy) | Gender differences in psychopathic traits, attachment, and cognitive emotion regulation strategies (CERS):

| Attachment Styles and Psychopathy |

| Kyranides et al. (2023) | To explore how anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions, maternal and paternal factors predict CU traits in women and men separately | The Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) Parent Adult-Child Relationship Questionnaire (PACQ) | Inventory of Callous- Unemotional Traits (ICU) (Callousness, Unemotional, and Uncaring) | Gender differences in CU traits:

| Attachment Styles and Psychopathy |

| Walsh et al. (2019) | Examine whether the four factors of psychopathy were differentially associated with attachment domains and whether there were gender differences in the associations between psychopathic traits and attachment problems | Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) | Self-Report Psychopathy-Short Form (SRP-SF) (Interpersonal, Affective, Lifestyle, and Antisocial factors) | Attachment and psychopathic traits in women:

| Attachment Styles and Psychopathy |

| Study | Design Type | Location and Setting | Sample Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex|Age (M/SD) | Size (n) | Ethnicity/Race | |||

| Arrigo and Griffin (2004) | Qualitative Case study | USA; N/A | woman Aileen Wuornos | 1 woman | N/A |

| Bloxsom et al. (2021) | Quantitative non-randomized study | United Kingdom; Community | Women (M = 26.65, SD = 11.65) Range 18 to 71 years | 262 women | White British (42.4%), White Other (31.7%), Asian (8.4%), Hispanic or Latino (5.0%), Black or African American (2.7%), Native American (1.1%), Other (5%) and ‘Prefer not to say’ (3.8%) |

| Doroszczyk and Talarowska (2023) | Quantitative non-randomized study | N/A; Community | women and men Range 18 to 45 years | 150 (129 women) | N/A |

| Eisenbarth et al. (2018) | Quantitative non-randomized study | USA; Prison | women offenders (M = 34.23; SD = 7.06); Range 21 to 54 years | 155 women offenders | Hispanic |

| Farrington and Bergstrøm (2023) | Descriptive—Quantitative and Qualitative | United Kingdom; Community | women and men M = 25.4 (women) | 551 (260 women) | N/A |

| Kyranides and Neofytou (2021) | Quantitative non-randomized study | United Kingdom; Community | women and men (M = 35.11, SD = 13.49) Range 18 to 70 years | 338 (231 women) | N/A |

| Kyranides et al. (2023) | Quantitative non-randomized study | United Kingdom; Community | women and men (M = 30.96, SD = 11.66) Range 18 to 72 years | 1149 (752 women) | N/A |

| Walsh et al. (2019) | Quantitative non-randomized study | USA; Community | women and men (M = 20.52, SD = 3.98) for women | 590 (206 women) | European Americans (64.6%), African Americans (14.9%), Asian Americans (7.6%), Latino/Hispanic (10%) |

| Authors | Screening Questions | Quantitative Descriptive | Qualitative | Mixed Methods | QA | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | ||

| Arrigo and Griffin (2004) | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| Bloxsom et al. (2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| Doroszczyk and Talarowska (2023) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| Eisenbarth et al. (2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 |

| Farrington and Bergstrøm (2023) | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 4 |

| Kyranides and Neofytou (2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| Kyranides et al. (2023) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 |

| Walsh et al. (2019) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

Attachment Styles and Psychopathy:

|

| Implications for Research | Implications for Practices and Policy |

|---|---|

| Expand the cultural and sociodemographic diversity of samples to understand how intersectional factors (gender, class, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc.) modulate the relationship between attachment and psychopathy. Develop longitudinal studies to examine the evolution of attachment configurations and psychopathic traits over time, clarifying the directionality of the association. Investigate integrative models that connect dimensions of attachment (e.g., Internal Working Models) with neurobiological, emotional, and social factors in the expression of female psychopathy. Promote greater theoretical and methodological integration between research on childhood and adult attachment, using compatible constructs and instruments across the lifespan. Use mixed methods and methodological triangulation (self-report, interviews, behavioural measures) to reduce social desirability bias and enhance data validity. | Interventions should emphasise the promotion of secure attachment and positive parenting practices to mitigate the risk of psychopathy in women. Sex differences in attachment styles and psychopathic traits emphasize the need for personalized interventions that meet the unique needs of women with psychopathic traits. Develop attachment-based interventions, such as MBT (Mentalization-Based Treatment) and ABFT (Attachment-Based Family Therapy), tailored to the emotional and relational profiles of women. Early intervention programs should be implemented to address risk factors associated with psychopathy, such as parental conflict and negative parenting styles. Adapt therapeutic programmes to be gender-sensitive, addressing the specific difficulties of women with insecure attachment, such as mistrust, fear of rejection, or emotional dysregulation. Apply attachment-based approaches in community settings, such as schools, primary healthcare, and family support centres, rather than limiting their use to clinical or correctional environments. Policies aimed at improving access to mental health services and support for individuals with psychopathic traits, especially women, could contribute to better outcomes and reduced recidivism rates. Promote positive parenting programmes and early family interventions in contexts of adversity to help prevent the intergenerational transmission of psychopathic traits and insecure attachment. Encourage policies that ensure equitable access to early childhood care, such as emotionally attuned daycare services, particularly in socioeconomically vulnerable areas. Support emotional literacy and parenting campaigns that make key attachment concepts accessible to the general population Integrate attachment dimensions (e.g., avoidant and anxious styles) into forensic risk assessment protocols to better identify women with higher CU/affective traits and guide individualized treatment planning. Women with elevated CU traits may benefit from attachment-based interventions (e.g., MBT, ABFT) that target empathic engagement, emotion regulation, and treatment adherence. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinheiro, M.L.; Machado, A.B.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Caridade, S.; Cunha, O. Exploring Attachment-Related Factors and Psychopathic Traits: A Systematic Review Focused on Women. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091293

Pinheiro ML, Machado AB, Gonçalves RA, Caridade S, Cunha O. Exploring Attachment-Related Factors and Psychopathic Traits: A Systematic Review Focused on Women. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091293

Chicago/Turabian StylePinheiro, Marina Leonor, Ana Beatriz Machado, Rui Abrunhosa Gonçalves, Sónia Caridade, and Olga Cunha. 2025. "Exploring Attachment-Related Factors and Psychopathic Traits: A Systematic Review Focused on Women" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091293

APA StylePinheiro, M. L., Machado, A. B., Gonçalves, R. A., Caridade, S., & Cunha, O. (2025). Exploring Attachment-Related Factors and Psychopathic Traits: A Systematic Review Focused on Women. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091293