Occupational Deviance Among University Counselors in China: The Negative Predictive Role of Professional Identity and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Occupational Deviance

1.2. Professional Identity and Occupational Deviance

1.3. Self-Control and Occupational Deviance

1.4. Moderating Effect of Self-Control

1.5. The Goal of This Study

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

2.3. Survey Tools

2.3.1. General Information Questionnaire

2.3.2. Professional Identity Questionnaire

2.3.3. Self-Control Questionnaire

2.3.4. Occupational Deviance Questionnaire

2.3.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Normality Test and Common Method Bias Assessment

3.2. Descriptive Analysis of Key Variables

3.3. Partial Correlation and Collinearity Analysis

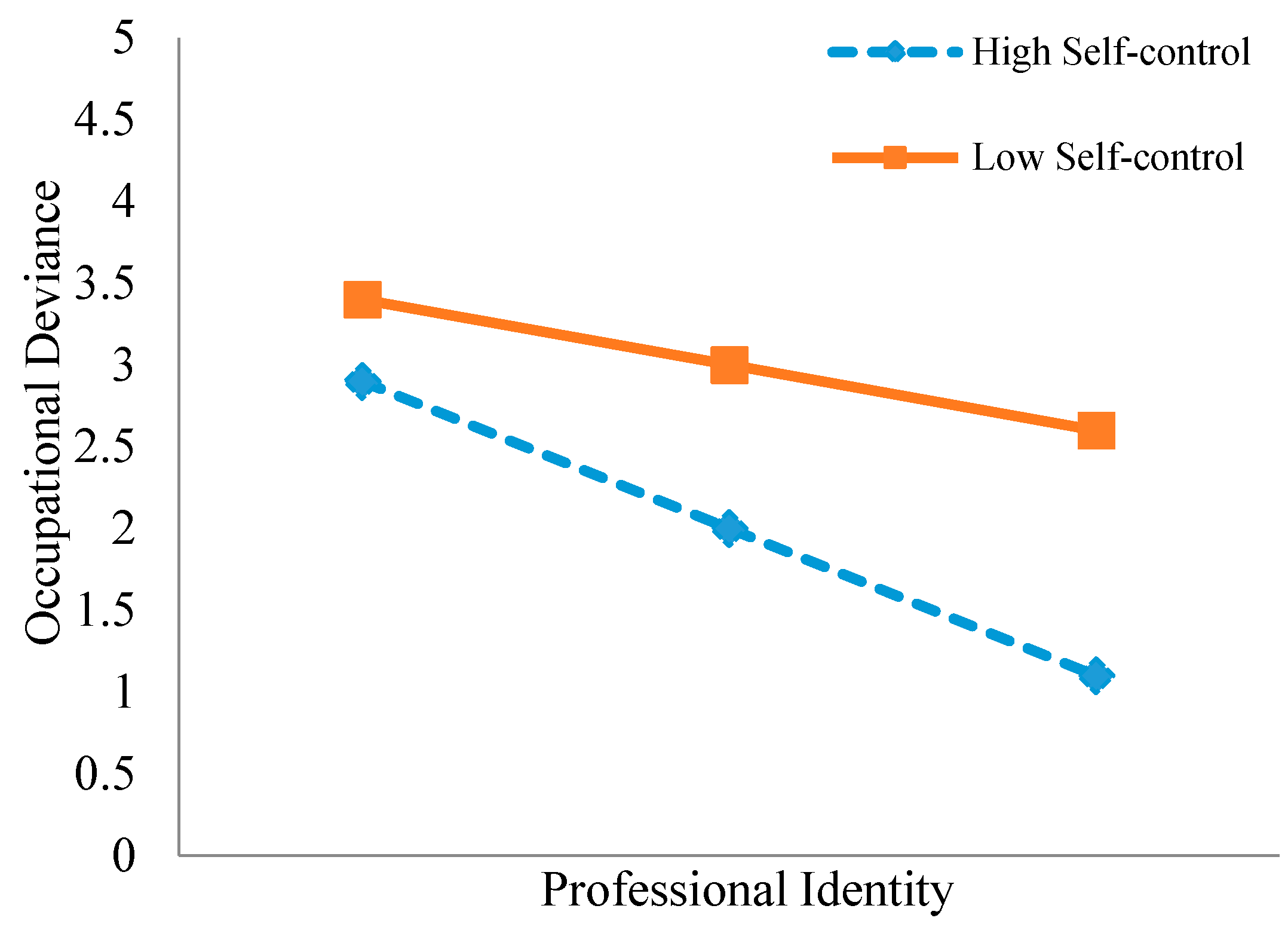

3.4. Moderating Effect Analysis of Self-Control

4. Discussion

4.1. Occupational Deviance Among Counselors Is Observed to Occur at Relatively Low Levels

4.2. Professional Identity Negatively Predicts Occupational Deviance

4.3. The Moderating Role of Self-Control in the Relationship Between Professional Identity and Occupational Deviance

5. Summary

5.1. Research Conclusions

- (1)

- Occupational deviance among counselors is observed to occur at relatively low levels.

- (2)

- Counselors’ professional identity significantly and negatively predicts occupational deviance.

- (3)

- Self-control has a significant moderating effect on the negative relationship between professional identity and occupational deviance, enhancing the negative predictive relationship between these variables.

5.2. Research Limitations

5.3. Research Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, C. (2021). A leader’s emotional self-control and management of others impacts a school’s climate. Journal of Invitational Theory and Practice, 25, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilano-Barbosa, D., Paredes, L., & Froylán, E. (2022). Moral emotions when reading quotidian circumstances in contexts of violence: An fMRI study. Adaptive Behavior, 30(2), 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H. (2018). Computer-specific parental management and online deviance across gender in South Korea: A test of self-control theory. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 12(1), 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Canadian Journal of Sociology-cahiers Canadiens De Sociologie, 2, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, D. E., Casey, J. E., Visser, R. D., & Headley, K. N. (2012). How do teachers make judgments about ethical and unethical behaviors? Toward the development of a code of conduct for teachers. Teaching & Teacher Education, 28(6), 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, D. C. (1981). Regression diagnostics—identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 32(2), 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, L. L., Mink, P. J., Kamrud, J. W., Jeruzal, J. N., & Stevens, A. C. (2019). Social support outside the workplace, coping styles, and burnout in a cohort of EMS providers from Minnesota. Workplace Health & Safety, 67(8), 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R. (1988). The evolution of reciprocity in sizable groups. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 132(3), 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. H., & Tan, L. X. (2010). A preliminary exploration of the construction of teachers’ professional ethics of university counselors. Educational Exploration, 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G., & Zhao, X. D. (2022). Research on the construction of teachers’ professional ethics of university counselors in the new era. Journal of Qingdao University of Science and Technology (Social Sciences Edition), 3, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Xu, K., Luo, L., & Chen, Y. (2024). A study of university counselors’ coping styles under occupational stress: Mediating and moderating effects of occupational emotions. Current Psychology, 43(44), 33856–33866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, Z., Zerom, D., & Turel, O. (2010). A modified kolmogorov-smirnov test for normality. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control and grit: Related but separable determinants of success. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(5), 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J., Wen, Z. L., Liang, D. M., & Li, N. N. (2015). Analysis of moderating effect based on multiple regression. Journal of Psychological Science, 38(3), 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, S. G., Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. (1995). Measurement, design, and analysis: An integrated approach. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(419), 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X. G., Zhang, Y., Shao, L. H., Fu, H. Y., & Cheng, N. (2024). The necessity, dilemmas, and countermeasures of the construction of the counselor team. China Metallurgical Education, (6), 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. American Political Science Review, 84(2), 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. (2023). Reflections on strengthening the construction of teacher ethics and conduct in universities in the new Era. International Journal of Mathematics and Systems Science, 6(3), 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G. M., & Dai, H. (2015). Analysis of the current situation and countermeasures of the anomie of contemporary university counselors’ professional ethics. Journal of Lanzhou Institute of Education, 2, 66–67+154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L. F. (2022). Research on the existing problems and countermeasures of the professional ethics of vocational university counselors. Journal of Zhejiang Institute of Communications, 1, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht, M., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2012). What is ego depletion? Toward a mechanistic revision of the resource model of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarwan, A. S., Frehat, A. M., & Basem, M. (2020). Educational counselors’ self-efficacy and professional competence. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(1), 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue—Contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, C. M., Smith, E. R., & Kidder, L. H. (1991). Research methods in social relations (6th ed.). Holt Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, C. (2020). Governance of unethical behaviors in teachers’ professional ethics in universities from the perspective of the “Three Nos” mechanism. Education and Examinations, 3, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. M. (2024). Construction of the professional ethics of vocational university counselors in the new era: Value, current situation, and path. Modern Business Trade Industry, 45(15), 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. N., Wang, M. F., Feng, X. J., Bai, X., Fang, J., & Zheng, W. K. (2024). The influence of neurotic personality on the mobile phone addiction tendency of nursing undergraduates: The chain mediating effect of perceived stress and self-control. Sichuan Mental Health, 37(1), 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. (2023). A theoretical review on the interplay among EFL teachers’ professional identity, agency, and positioning. Heliyon, 9(4), e15510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. W., Yang, H. W., Wang, L. J., & Ren, Y. Y. (2021). An analysis of the relationship between psychological resilience and subjective well-being among university counselors. Psychological Monthly, 16(21), 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Z., & Song, Z. H. (2024). Review and prospect of the research on teachers’ professional ethics in universities in China in the new century. Journal of Huanghe University of Science and Technology, 7, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Y., Li, J. Y., & Wang, L. Q. (2016). Research on the current situation of the professional identity of university counselors. Hubei Social Sciences, 1, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. C., & Chen, D. (2022). Cultivation of the professional ethics of university counselors: Desired values, actual dilemmas, and appropriate paths. Journal of Guilin University of Aerospace Technology, 1, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T., Cheng, L. M., Qin, L. X., & Xiao, S. Y. (2021). Reliability and validity test of the Chinese version of the brief self-control scale. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29(1), 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M. (2021). The connotation and reflection of the construction of teachers’ professional ethics in the new era. Journal of Capital University of Physical Education and Sports, 9, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q. N., & Qu, J. W. (2019). Discussion on the construction of teachers’ professional ethics of excellent counselors. School Party Building and Ideological Education, 21, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, B. (2004). Self-control in the general theory of crime: Theoretical implications of a measurement problem. Theoretical Criminology, 8(1), 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2004). Causal explanation, qualitative research, and scientific inquiry in education. Educational Researcher, 33(2), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ME of PRC (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China). (2017). Regulations on the construction of counselor teams in ordinary universities (pp. 9–29). Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2017/content_5244874.htm (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Merton, R. K. (1938). Social structure and anomie. American Sociological Review, 3(5), 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. (1991). A three—component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milon, L. L. O. (2021). Authentic leadership as a mediator between professional identity, ethical climate, citizenship behavior and political behavior. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(7), 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1998). Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature, 393(6685), 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X. R. (2019). Research on the countermeasures for the construction of the professional ethics of private university counselors in the new era. The Guide of Science & Education, 21, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, M. E. (2021). Emotion regulation skills and self-control as predictors of resilience in teacher candidates. International Education Studies, 14(6), 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauster, E., Ferrucci, P., Tandoc, E., & Walker, T. (2021). Advertising primed: How professional identity affects moral reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(1), 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental & quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 33, 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y., Zhao, W. F., & Zhang, Y. F. (2018). Identification and construction: A study on the construction of teachers’ professional ethics based on the identity recognition of young teachers in universities—Taking the University of International Business and Economics as an example. New Education Era Electronic Magazine (Teachers’ Edition), 29, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, X. Q., Li, J. Y., Zhao, C. R., Liu, M. F., & Ye, B. J. (2021). Development and validation of an unethical professional behavior tendencies scale for student teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 770681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. P. (2017). Research on the construction paradigm of the professional ethics of university counselors from the perspective of competency. Heilongjiang Researches on Higher Education, 10, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Tian, L., Pang, Y., Wang, H., & Wang, R. (2023). Constraints and improvement paths of teacher ethics construction for Chinese higher education institutions in the new era. Frontiers in Educational Research, 6(21), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Q., Wang, J., Wang, J., & Wang, D. J. (2019). The structure, measurement equivalence, and detection rate of unethical professional behaviors of primary and secondary school teachers. Educational Research Monthly, 9, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Huang, C. Y., & Zhang, Q. (2019). The influence of negative emotions on organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive behavior: From the perspective of self-control. Management Review, 31(12), 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z. L., & Ye, B. J. (2014). Analysis of mediating effect: Methods and model development. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(5), 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. L. (2010). Practical statistics for questionnaire data analysis: SPSS operation and application (pp. 207–208). Chongqing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. H., & Yuan, C. Z. (2017). Research on the professional identity of university counselors. Journal of Hangzhou Dianzi University (Social Sciences), 13(1), 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. Y. (2022). The professional personality of university counselors: Structure, influencing factors, and its action mechanism [Doctoral Dissertation, Fujian Normal University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N., Fu, Z., Zhang, H., Piao, L., Xoplaki, E., & Luterbacher, J. (2015). Detrended partial–cross—correlation analysis: A new method for analyzing correlations in complex system. Scientific Reports, 5, 8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. J., Wang, Z., & Chao, L. M. (2018). Research on the current situation of the professional identity of university counselors in western universities in Inner Mongolia. Journal of Hulunbuir University, 26(5), 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. (2021). Research on the path of the construction of teachers’ professional ethics of university counselors from the perspective of Bergson’s philosophy of Life. The Science Education Article Collects (Issue in the Second Half of the Month), 3, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Zhang, J., Hua, W., & Zhao, M. (2024). How does enlistment motivation shape organizational commitment? the role of career identity and organizational support. Psychological Reports, 127(1), 299–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Variables | Form | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 153 | 42.15 |

| Female | 210 | 57.85 | |

| Age ① | <30 years old | 169 | 46.56 |

| 30–39 years old | 152 | 41.87 | |

| 40–49 | 36 | 9.92 | |

| ≥50 years old | 6 | 1.65 | |

| Marital status | Yes | 237 | 65.29 |

| No | 126 | 34.71 | |

| Years of service | <5 years | 148 | 40.77 |

| 5–10 years | 113 | 31.13 | |

| 11–15 years | 63 | 17.36 | |

| >15 years | 39 | 10.74 | |

| Professional title ② | Assistant | 57 | 15.70 |

| Lecturer | 230 | 63.36 | |

| Associate Professor | 70 | 19.28 | |

| Professor | 6 | 1.66 | |

| Student caseload ③ | <200 students | 57 | 15.70 |

| 200–300 students | 78 | 21.49 | |

| >300 students | 228 | 62.81 | |

| Add up the total | 363 | 100 | |

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | Collinearity Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIF Value | Tolerance | |||||

| 1. Professional identity | 3.447 ± 1.239 | 1 | 4.954 | 0.194 | ||

| 2. Self-control | 3.954 ± 0.971 | 0.391 ** | 1 | 2.826 | 0.354 | |

| 3. Occupational deviance | 2.553 ± 1.230 | −0.509 ** | −0.412 ** | 1 | 4.171 | 0.253 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p | β | B | SE | t | p | β | |

| Constant | 1.870 | 0.224 | 8.3420 *** | 0.000 | - | 1.787 | 0.224 | 7.982 ** | 0.000 | - | 1.458 | 0.210 | 6.942 *** | 0.000 | - |

| Gender | 0.043 | 0.051 | 0.844 | 0.399 | 0.021 | 0.059 | 0.051 | 1.165 | 0.245 | 0.029 | 0.092 | 0.047 | 1.953 | 0.052 | 0.045 |

| Age | 0.022 | 0.044 | 0.500 | 0.618 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.043 | 0.437 | 0.662 | 0.014 | 0.043 | 0.040 | 1.081 | 0.280 | 0.031 |

| Years of service | −0.017 | 0.029 | −0.565 | 0.572 | −0.017 | −0.009 | 0.029 | −0.295 | 0.768 | −0.009 | 0.016 | 0.027 | 0.597 | 0.551 | 0.016 |

| Marital status | 0.006 | 0.065 | 0.092 | 0.926 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.064 | 0.148 | 0.883 | 0.005 | 0.061 | 0.060 | 1.020 | 0.308 | 0.029 |

| Professional title | 0.023 | 0.021 | 1.097 | 0.273 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.020 | 1.122 | 0.263 | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 1.025 | 0.306 | 0.022 |

| Student caseload | 0.006 | 0.030 | 0.210 | 0.834 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.030 | 0.740 | 0.460 | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.896 | 0.371 | 0.021 |

| Professional identity | −0.407 | 0.023 | −18.626 ** | 0.000 | −0.404 | −0.491 | 0.038 | −6.059 ** | 0.000 | −0.488 | −0.480 | 0.035 | −7.980 ** | 0.000 | −0.477 |

| Self-control | −0.109 | 0.039 | −2.810 ** | 0.005 | −0.109 | −0.111 | 0.036 | −3.125 ** | 0.002 | −0.111 | |||||

| Professional identity × Self-control | −0.154 | 0.019 | −8.062 ** | 0.000 | −0.171 | ||||||||||

| R2 | 0.815 | 0.819 | 0.847 | ||||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.811 | 0.815 | 0.843 | ||||||||||||

| F | F (7,355) = 223.075, p = 0.000 | F (8,354) = 199.968, p = 0.000 | F (9,353) = 217.105, p = 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.815 | 0.004 | 0.028 | ||||||||||||

| ΔF | F (7,355) = 223.075, p = 0.000 | F (1,354) = 7.895, p = 0.005 | F (1,353) = 64.995, p = 0.000 | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, T.; Luan, X.; Dong, S. Occupational Deviance Among University Counselors in China: The Negative Predictive Role of Professional Identity and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091278

Chen T, Luan X, Dong S. Occupational Deviance Among University Counselors in China: The Negative Predictive Role of Professional Identity and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091278

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Tiantian, Xianjun Luan, and Shenghong Dong. 2025. "Occupational Deviance Among University Counselors in China: The Negative Predictive Role of Professional Identity and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091278

APA StyleChen, T., Luan, X., & Dong, S. (2025). Occupational Deviance Among University Counselors in China: The Negative Predictive Role of Professional Identity and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091278