Development and Validation of the Safety Behavior Assessment Form-PTSD Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scale Development

2.1. Overview

2.2. Preliminary Scale Development-SBAF-PTSD Scale (12 Item Version)

3. Study 1

3.1. Study 1—Method

3.1.1. Overview

3.1.2. Participants

3.1.3. Measures

3.1.4. Data Analytic Procedures

3.2. Study 1—Results

3.2.1. Scale Composition of the SBAF-PTSD

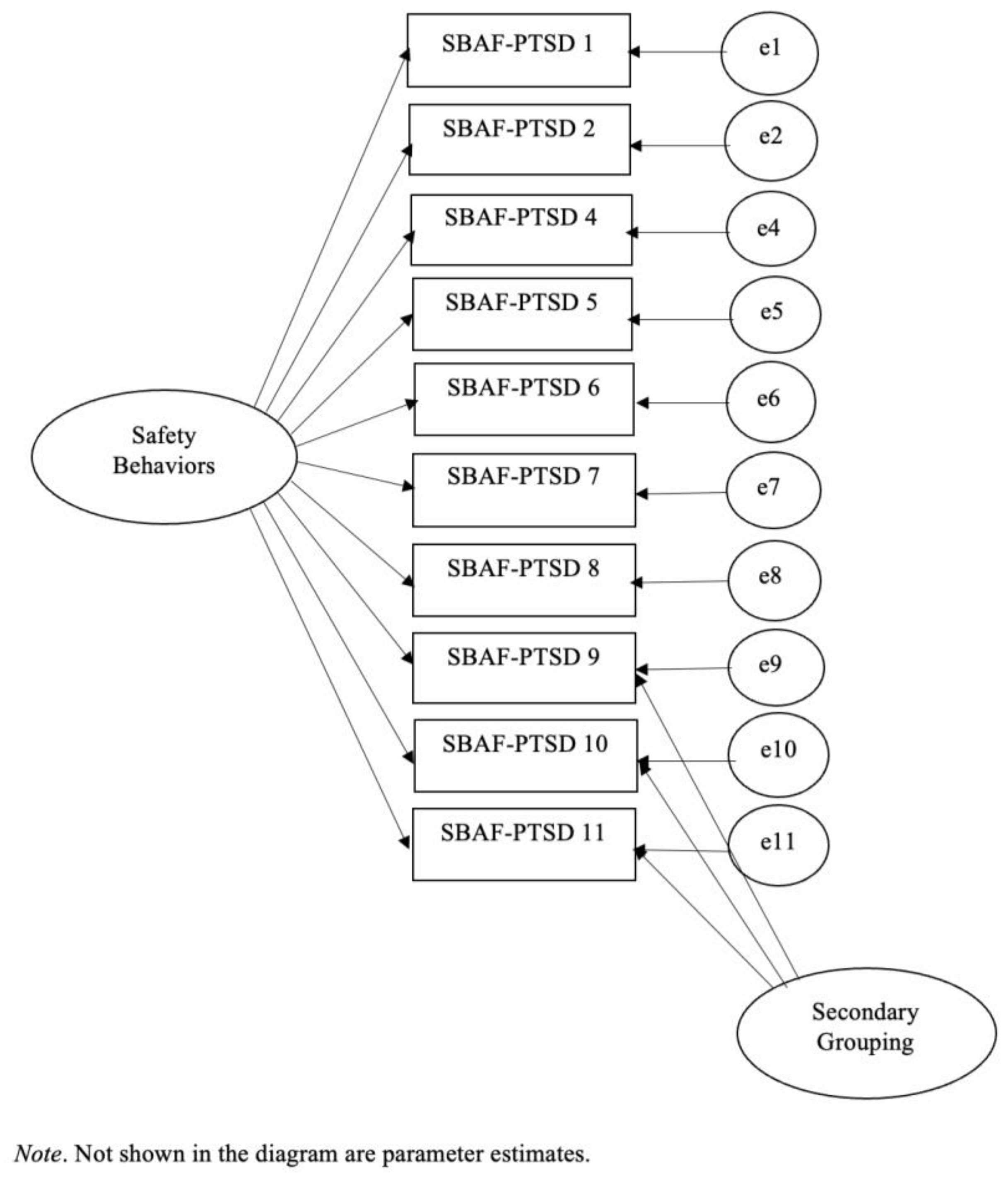

3.2.2. Examination of Model Fit Indices Indicated Best Fit for Model 3

3.2.3. Correlations with Demographic Variables

3.2.4. Validity

3.3. Study 1—Discussion

4. Study 2

4.1. Study 2—Method

4.1.1. Overview

4.1.2. Participants

4.1.3. Measures

4.1.4. Procedure

4.1.5. Data Analytic Procedures

4.2. Study 2—Results

4.2.1. Scale Composition

4.2.2. Reliability

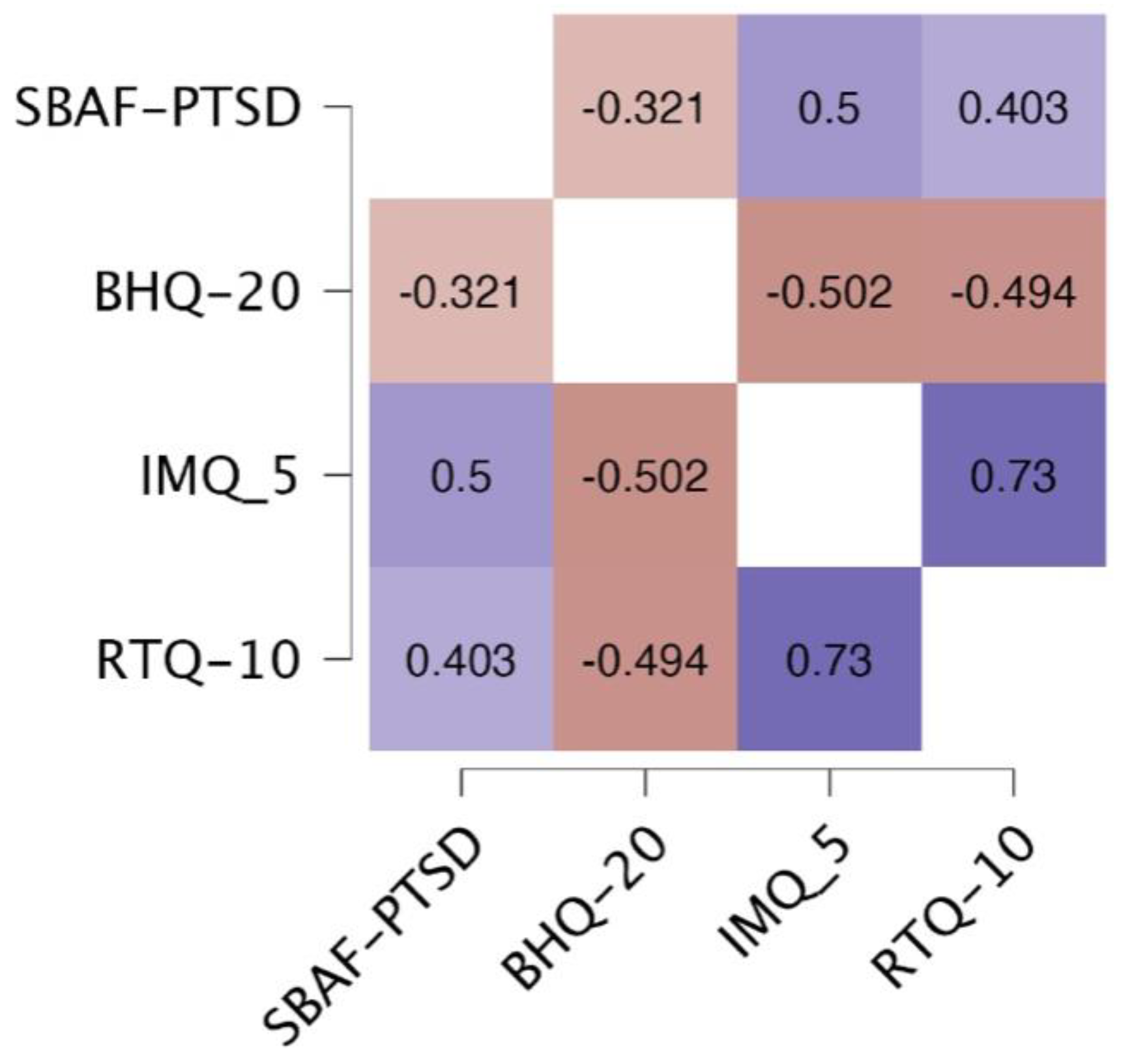

4.2.3. Validity

4.3. Study 2—Discussion

5. Study 3

5.1. Study 3—Method

5.1.1. Overview

5.1.2. Participants

5.1.3. Measures

5.1.4. Procedure

5.1.5. Data Analytic Procedures

5.2. Study 3—Results

5.2.1. Reliability

5.2.2. Validity

5.3. Study 3—Discussion

6. Study 4

6.1. Study 4—Method

6.1.1. Overview

6.1.2. Participants

6.1.3. Treatments and Therapists

6.1.4. Measures

6.1.5. Data Analytic Procedures

6.2. Study 4—Results

6.3. Study 4—Discussion

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTSD | posttraumatic stress disorder |

| SBAF | Safety Behavior Assessment Form |

Appendix A

| Never | Sometimes | Often | Always |

- Scope places out before entering.

- Sit with back to wall.

- Check yard or the area around your home (“Perimeter Checks”).

- Make up contingency plans in case someone is physically aggressive or there is some kind of emergency.

- Walk slowly to let someone pass who is close behind.

- Watch others for signs of danger.

- Check locks on doors or windows.

- Pretend I do not see or recognize someone so that I do not have to speak with them.

- Cut conversation short.

- Leave events or activities early.

References

- Baker, H., Alden, L. E., & Robichaud, M. (2021). A comparison of coping and safety-seeking behaviors. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(6), 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L. D., & Goodson, J. T. (2023). Preliminary validation of the IMQ-5: A brief intrusive memory questionnaire for PTSD. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(3), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesdo-Baum, K., Jenjahn, E., Hofler, M., Lueken, U., Becker, E. S., & Hoyer, J. (2012). Avoidance, safety behavior, and reassurance seeking in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 29, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakey, S. M., Kirby, A. C., McClure, K. E., Elbogen, E. B., Beckham, J. C., Watkins, L. L., & Clapp, J. D. (2020). Posttraumatic safety behaviors: Characteristics and associations with symptom severity in two samples. Traumatology, 26, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2015). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. A., & Tung, E. S. (2018). The contribution of worry behaviors to the diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavior Assessment, 40, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2019). Constructing validity: New developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychological Assessment, 31(12), 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, K. S., Wiener, D., Rauch, S. A. M., Tuerk, P. W., Wangelin, B., & Acierno, R. (2023). Individual symptom reduction and post-treatment severity: Varying levels of symptom amelioration in response to prolonged exposure for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services, 20(1), 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunmore, E., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (1999). Cognitive factors involved in the onset and maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodson, J. T., & Haeffel, G. H. (2018). Preventative and restorative safety behaviors: Effects on exposure treatment outcomes and risk for future anxious symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1657–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodson, J. T., Haeffel, G. J., Raush, D., & Hershenberg, R. (2016). The safety behavior assessment form: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig-Lang, S., & Petermann, F. (2010). Tolerate or eliminate: A systematic review of the effects of safety behaviors across anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig-Lang, S., Richter, J., Lang, T., Gerlach, A. L., Fehm, L., Alpers, G. W., Ströhle, A., Kircher, T., Deckert, J., Gloster, A. T., & Wittchen, H. U. (2014). The role of safety behaviors in exposure-based treatment for panic disorder and agoraphobia: Associations to symptom severity, treatment course, and outcome. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershenberg, R., Smith, R. V., Goodson, J. T., & Thase, M. E. (2018). Activating veterans toward sources of reward: A pilot report on development, feasibility, and clinical outcomes of a 12-week behavioral activation group treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 25(1), 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J. H. (2006). Factor analysis in counseling psychology research, training, and practice: Principles, advances, and applications. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 684–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, A., Meyer, J. M., Whisman, M. A., Deacon, B. J., & Arch, J. J. (2019). Safety behaviors, experiential avoidance, and anxiety: A path analysis approach. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 64, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kopta, S. M., & Lowry, J. L. (2002). Psychometric evaluation of the behavioral health questionnaire-20: A brief instrument for assessing global mental health and the three phases of psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 12(4), 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, P. M., Thibodeau, M. A., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2014). Trait repetitive negative thinking: A brief transdiagnostic assessment. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 5(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monson, C. M., Fredman, S. J., & Dekel, R. (2010). Posttraumatic stress disorder in an interpersonal context. In J. G. Beck (Ed.), Interpersonal processes in the anxiety disorders: Implications for understanding psychopathology and treatment (pp. 179–208). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1967). Psychometric theory (Vol. 226). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Piccarillo, M. L., Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2015). Safety behaviors in adults with social anxiety: Review and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 47, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, A., Bovin, M. J., Smolenski, D. J., Marx, B. P., Kimerling, R., Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Kaloupek, D. G., Schnurr, P. P., Kaiser, A. P., Leyva, Y. E., & Tiet, Q. Q. (2016). The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salkovskis, P. M. (1991). The importance of behaviour in the maintenance of anxiety and panic: A cognitive account. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 19, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkovskis, P. M., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., Wells, A., & Gelder, M. G. (1999). An experimental investigation of the role of safety-seeking behaviours in the maintenance of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spix, M., Melles, H., & Jansen, A. (2023). From bad to worse: Safety behaviors exacerbate eating disorder fears. Behavioral Sciences, 13(7), 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, H. E., & Tinsley, D. J. (1987). Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the national center for PTSD. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Woolston, C., Chavez, G., Kaur, K., & Asnaani, A. (2022). Impact of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms on baseline self-reported safety behaviors during the trauma film paradigm [Senior Honors thesis, University of Utah]. [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann, J. H., Jordan, A. H., Weathers, F. W., Resick, P. A., Dondanville, K. A., Hall-Clark, B., Foa, E. B., Young-McCaughan, S., Yarvis, J. S., Hembree, E. A., Mintz, J., Peterson, A. L., & Litz, B. T. (2016). Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychological Assessment, 28, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Content | M | SD | P vs. R | V vs. S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scope places out before entering. | 2.17 | 0.87 | P | V |

| 2 | Sit with back to wall. | 2.40 | 0.81 | P | V |

| 3 | Rush through the stores or go directly to desired items and leave as quickly as possible. | 2.07 | 0.98 | P | - |

| 4 | Check yard or the area around your home (“Perimeter Checks”). | 1.85 | 1.00 | P | V |

| 5 | Make up contingency plans in case someone is physically aggressive or there is some kind of emergency. | 2.28 | 0.89 | P | V |

| 6 | Walk slowly to let someone pass who is close behind. | 2.04 | 0.94 | R | S |

| 7 | Watch others for signs of danger. | 2.39 | 0.77 | P | V |

| 8 | Check locks on doors or windows. | 2.43 | 0.83 | P | V |

| 9 | Pretend I do not see or recognize someone so that I do not have to speak with them. | 1.58 | 0.89 | P | S |

| 10 | Cut conversation short. | 1.76 | 0.78 | R | S |

| 11 | Leave events or activities early. | 2.01 | 0.88 | R | S |

| 12 | Stay on the outside of crowds and/or monitor for exits or escape routes. | 2.30 | 0.83 | P | V |

| Scale | M | SD | Score Range | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBAF–PTSD 10 | 20.87 | 5.54 | 0–30 | 0.84 |

| SBAF–PTSD Social | 5.34 | 2.15 | 0–9 | 0.80 |

| PHQ–9 | 15.63 | 6.20 | 0–27 | 0.86 |

| PCL–5 | 52.91 | 14.33 | 9–71 | 0.91 |

| Intrusions | 12.81 | 4.44 | 2–20 | 0.85 |

| Avoidance | 5.97 | 1.87 | 0–8 | 0.77 |

| Cognitions and Mood | 18.06 | 6.11 | 0–28 | 0.81 |

| Arousal | 15.99 | 4.65 | 1–24 | 0.76 |

| No Trauma Mean (SD) | Trauma/Minimal Sxs Mean (SD) | Trauma/Probable PTSD Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD–SBAF Scale | 11.2 (4.5) | 11.1 (4.8) | 13.8 (4.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goodson, J.T.; Fraizer, M.E.; Haeffel, G.J.; Brewczynski, J.; Baker, L.; Woolston, C.; Asnaani, A.; Roberge, E.M. Development and Validation of the Safety Behavior Assessment Form-PTSD Scale. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091248

Goodson JT, Fraizer ME, Haeffel GJ, Brewczynski J, Baker L, Woolston C, Asnaani A, Roberge EM. Development and Validation of the Safety Behavior Assessment Form-PTSD Scale. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091248

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoodson, Jason T., Madison E. Fraizer, Gerald J. Haeffel, Jacek Brewczynski, Lucas Baker, Caleb Woolston, Anu Asnaani, and Erika M. Roberge. 2025. "Development and Validation of the Safety Behavior Assessment Form-PTSD Scale" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091248

APA StyleGoodson, J. T., Fraizer, M. E., Haeffel, G. J., Brewczynski, J., Baker, L., Woolston, C., Asnaani, A., & Roberge, E. M. (2025). Development and Validation of the Safety Behavior Assessment Form-PTSD Scale. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091248