Stigma and Emotion Regulation in Intimate Partner Violence: A Pilot Exploratory Study with Victims, Offenders and Experts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Normative Framework of Gender-Based Violence and Intimate Partner Violence

1.2. The Scientific Literature on Gender-Based Violence and Intimate Partner Violence

1.3. Research Objectives and Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Background

- Generative DRs open up scenarios whereby the narrative about gender-based violence can be joined by elements other than just the phenomenon or the specific violence situation such that there are multiple storytelling possibilities;

- Stabilisation DRs close off that possibility, making all of a person’s discourses and actions revolve around the gender-based violence phenomenon/situation in only one narrative;

- Hybrid DRs foster the generative or stabilisation direction based on the DRs they link with.

2.2. Data Collection and Participants

3. Results

“The person loses his dignity, feels guilty. When she has problems with her husband, she avoids them”.

“[the victim is] weak, insecure”.

in which the text conveys support and comfort to the victim. However, since these terms are mostly used with Stabilisation DRs, the description about the victim appears relatively closed and limited, which may suggest that interventions could focus primarily on protection (see also (Murray et al., 2018)). As much as victim protection is a core concern in these situations, only focusing the interventions on this aspect could limit opportunities for the victim to develop skills that can enable them to identify critical interactions and behaviours acted out by their partner, potentially helping them to anticipate and respond to risk. Conversely, in promoting such skills, it might also increase the likelihood that victims will take more ownership in promptly contacting dedicated support services. It is also important to consider that experts operate within the institutional guidelines of anti-violence centres that may implicitly encourage a tendency towards Stabilisation DRs, emphasising protection over empowerment. The specific policies, procedures and cultural attitudes within centres could thus shape the DRs used by experts.“[the victim is] helpless, succubus, a frightened person”,

“[the offender is] overbearing, impulsive, verbally aggressive”.

“I have always got everything in life, what I want I get, I don’t care how other people are/what they want, it’s me who has to be well”.

“[The offender] is angry, disappointed, scared by the fact that he cannot accept the end of the relationship or the loss of his job due to anger in the workplace”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Reflections for Intervention

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The mission of Fondazione “Eugenio Ferrioli e Luciana Bo Onlus” is to support and help female victims of domestic violence and stalking, as well as children exposed to these dynamics, and to support and recover those who engage in violence and stalking through three expressly dedicated multidisciplinary services [https://www.fondazioneferriolibo.it/]. |

References

- Abramsky, T., Devries, K. M., Michau, L., Nakuti, J., Musuya, T., Kiss, L., Kyegombe, N., & Watts, C. (2016). Ecological pathways to prevention: How does the SASA! Community mobilisation model work to prevent physical intimate partner violence against women? BMC Public Health, 16(1), 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E. A., Gleckman-Krut, M., & Johnson, L. (2018). Silence, power, and inequality: An intersectional approach to sexual violence. Annual Review of Sociology, 44(1), 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, R., Emery, E., & Wong, M. (2013). Systematic review of prevention and management strategies for the consequences of gender-based violence in refugee settings. International Health, 5(2), 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, R. M., & Miragall, M. (2024). Gender matters: A critical piece in mental health. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 27, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, D., Moro, C., Orrù, L., & Turchi, G. P. (2024a). Pupils’ inclusion as a process of narrative interactions: Tackling ADHD typification through MADIT methodology. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D., Orrù, L., Moro, C., Salvarani, D., & Turchi, G. P. (2024b). Investigating AVHs narratives through text analysis: The proposal of Dialogic Science for tackling stigmatization. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, E. A., Klement, K. R., Kaye, L. K., & Pennington, C. R. (2019). The impact of gendered stereotypes on perceptions of violence: A commentary. Sex Roles, 81(1–2), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J. G., McNiff, J., Clapp, J. D., Olsen, S. A., Avery, M. L., & Hagewood, J. H. (2011). Exploring negative emotion in women experiencing intimate partner violence: Shame, guilt, and PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (2016). The social construction of reality. In Social theory re-wired (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, P. (2020). Pre-marital relationships and violence: Experiences of working middle class women in Delhi. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(1), 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, F., & Wendt, S. (2018). Opening doors: Women’s participation in feminist studies about domestic violence. Qualitative Social Work, 17(6), 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M. S., Belloso, M. L., & Royo Prieto, R. (2020). The application of feminist standpoint theory in social research. Investigaciones Feministas, 11(2), 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponnetto, P., Lenzo, V., Sardella, A., Prezzavento, G. C., Casu, M., & Quattropani, M. C. (2024). Breaking the silence: Exploring peritraumatic distress and negative emotions in male and female physical domestic violence victims. Health Psychology Research, 12, 92900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B. M., Kaestle, C. E., Walker, A., Curtis, A., Day, A., Toumbourou, J. W., & Miller, P. (2015). Longitudinal predictors of domestic violence perpetration and victimization: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (2011). Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, Istanbul., n. 210. Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal, P., Joshi, S. K., & Swahnberg, K. (2022). A qualitative study on gender inequality and gender-based violence in Nepal. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, G., Franco, C., Cenizo, M., Canestrari, C., Suárez-Relinque, C., Muzi, M., & Fermani, A. (2020). Myth acceptance regarding male-to-female intimate partner violence amongst Spanish adolescents and emerging adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Démonté, C. (2019). Prise en charge psychosexologique des auteurs de violences sexuelles en milieu carcéral. Soins Psychiatrie, 40, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Directive 2012/29/EU of the European parliament and of the council of 25 October 2012 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime, and replacing council framework decision 2001/220/JHA, EP, CONSIL, 315 OJ L. (2012). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2012/29/oj/eng (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Edwards, K. M., Waterman, E. A., Dardis, C. M., Ullman, S. E., Rodriguez, L. M., & Dworkin, E. R. (2021). A program to improve social reactions to sexual and dating violence disclosures reduces posttraumatic stress in subsequently victimized participants. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(3), 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, S., Szmodis, W., & Grace, K. (2020). Cambodian remarried women are at risk for domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(3–4), 828–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-Álvarez, C., Santirso, F. A., Gilchrist, G., Gracia, E., & Lila, M. (2023). Participants in court-mandated intervention programs for intimate partner violence perpetrators with substance use problems: A systematic review of specific risk factors. Psychosocial Intervention, 32(2), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 3, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C., Holden, C. J., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Velotti, P. (2016). Understanding the connection between self-esteem and aggression: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Aggressive Behavior, 42(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1963). Embarrassment and social organization (p. 548). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, A. M., Peters, B. J., Karantzas, G. C., Cameron, L. D., & Simpson, J. A. (2025). Intimate partner violence victimization, habitual emotion regulation strategies, and health during COVID-19. Psychology of Violence. [Google Scholar]

- Harré, R., & Gillett, G. (1994). The discursive mind. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L. L., & Kotsadam, A. (2015). Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health, 3(6), e332–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. (2014). La violenza contro le donne. Anno 2014—Istat. Available online: https://www.istat.it/tavole-di-dati/la-violenza-contro-le-donne-anno-2014/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- ISTAT. (2023). Le vittime di omicidio—Anno 2023—Istat. Available online: https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/le-vittime-di-omicidio-anno-2023/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- ISTAT. (2024). Il numero di pubblica utilità 1522: Dati trimestrali del III trimestre 2024—Istat. Available online: https://www.istat.it/tavole-di-dati/il-numero-di-pubblica-utilita-1522-dati-trimestrali-del-iii-trimestre-2024/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Iudici, A., Antonello, A., & Turchi, G. (2019a). Intimate partner violence against disabled persons: Clinical and health impact, intersections, issues and intervention strategies. Sexuality & Culture, 23(2), 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iudici, A., Favaretto, G., & Turchi, G. P. (2019b). Community perspective: How volunteers, professionals, families and the general population construct disability: Social, clinical and health implications. Disability and Health Journal, 12(2), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iudici, A., Gagliardo Corsi, A., & Turchi, G. (2020). Evaluating a case of parent separation in social services through a text analysis: Clinical and health implications. Journal of Social Service Research, 46(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. B., & Johnson, M. P. (2008). Differentiation among types of intimate partner violence: Research update and implications for interventions. Family Court Review, 46(3), 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. C., & Prock, K. A. (2018). «I still feel like I am not normal»: A review of the role of stigma and stigmatization among female survivors of child sexual abuse, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 19(5), 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, K. R., Sagarin, B. J., & Skowronski, J. J. (2019). Accusers lie and other myths: Rape myth acceptance predicts judgments made about accusers and accused perpetrators in a rape case. Sex Roles, 81(1), 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M. P. (2014). The RESTORE program of restorative justice for sex crimes: Vision, process, and outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(9), 1623–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La storia del femminicidio di Giulia Cecchettin, dall’inizio. (2023, November 20) Il Post. Available online: https://www.ilpost.it/2023/11/20/omicidio-giulia-cecchettin/ (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Latta, R. E., & Goodman, L. A. (2011). Intervening in partner violence against women: A grounded theory exploration of informal network members’ experiences. The Counseling Psychologist, 39(7), 973–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T., Fedoroff, J. P., & Briken, P. (2020). A narrative review of research on clinical responses to the problem of sexual offenses in the last decade. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 38(2), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, G. H., Huebner, D. R., & Joas, H. (2015). Mind, self, and society: The definitive edition. University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo20099389.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Mouilso, E. R., & Calhoun, K. S. (2016). Personality and perpetration: Narcissism among college sexual assault perpetrators. Violence Against Women, 22(10), 1228–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. E., Crowe, A., & Overstreet, N. M. (2018). Sources and components of stigma experienced by survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(3), 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naismith, I., Ripoll-Nuñez, K., & Pardo, V. (2021). Group compassion-based therapy for female survivors of intimate-partner violence and gender-based violence: A pilot study. Journal of Family Violence, 36, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, J., Romanelli, M., Perno, A., Laugelli, E., & Turchi, G. (2020). «Gender differences» and health: A research conducted on the users of the inOltre service. Rivista di Psicologia Clinica, 15(1), 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, P. (2019a). Public perceptions and moral tales. In Domestic violence and psychology (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson, P. (2019b). The social construction of intimate partner violence and abuse: Myths, legends and formula stories. In Domestic violence and psychology (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Oram, S., Khalifeh, H., & Howard, L. M. (2017). Violence against women and mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Z. D., Voller, E. K., Polusny, M. A., & Murdoch, M. (2011). Prevalence and consequences of adult sexual assault of men: Review of empirical findings and state of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedalue, A., Gilbertson, A., Alexeyeff, K., & Klein, E. (2020). Is gender-based violence a social norm? Rethinking power in a popular development intervention. Feminist Review, 126(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragetlie, R., Sano, Y., Antabe, R., & Luginaah, I. (2020). Married women’s experiences of intimate partner violence and utilization of antenatal health care in Togo. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives, 23, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M. G., do Rosário Lima, V. M., & Amaral-Rosa, M. P. (2018). IRAMUTEQ software and discursive textual analysis: Interpretive possibilities. In World conference on qualitative research (pp. 58–72). Cham; Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudales, A. M., Short, N. A., & Schmidt, N. B. (2019). Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between trauma type and PTSD symptoms in a diverse trauma-exposed clinical sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Gutierrez, L., Izaguirre Choperena, A., & López Belloso, M. (2024). The study of gender-based violence through a narrative approach: Evidence from the European project IMPROVE. Social Sciences, 13(7), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruork, A. K., McLean, C. L., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2022). It happened matters more than what happened: Associations between intimate partner violence abuse type, emotion regulation, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Violence Against Women, 28(5), 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, B. (2018). Police perceptions in intimate partner violence cases: The influence of gender and sexual orientation. Journal of Crime and Justice, 41(2), 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint Arnault, D. M. (2017). The use of the clinical ethnographic narrative interview to understand and support help seeking after gender-based violence. TPM. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 24(3), 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarduzio, J. A., Carlyle, K. E., Harris, K. L., & Savage, M. W. (2017). “Maybe she was provoked”: Exploring gender stereotypes about male and female perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 23(1), 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C. M., Keilholtz, B. M., Palmer, M., & Vail, S. L. (2024). Mental and physical health correlates for emotional intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1), 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Sunmola, A. M., Mayungbo, O. A., Ashefor, G. A., & Morakinyo, L. A. (2020). Does relation between women’s justification of wife beating and intimate partner violence differ in context of husband’s controlling attitudes in Nigeria? Journal of Family Issues, 41(1), 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarzia, L. (2021). Toward an ecological understanding of intimate partner sexual violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(23–24), 11704–11727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetikcok, R., Ozer, E., Cakir, L., Enginyurt, O., İscanli, M. D., Cankaya, S., & Ozer, F. (2016). Violence towards women is a public health problem. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 44, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, G. P., Bassi, D., Agnoletti, C., Riva, M. S. D., Iudici, A., & Orrù, L. (2023a). What are they gonna think about me? An innovative text analysis on social anxiety and Taijin kyofusho through MADIT methodology. Human Arenas, 8, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G. P., Bassi, D., Cavarzan, M., Camellini, T., Moro, C., & Orrù, L. (2023b). Intervening on global emergencies: The value of human interactions for people’s health. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G. P., Celleghin, E., & Sperotto, M. (2012). Sport e media. La configurazione della violenza in ambito sportivo. Ricerca di base e risultati operativi. Upsel Domeneghini. [Google Scholar]

- Turchi, G. P., & Romanelli, M. (2019). Dialogical mediation as an instrument to promote health and social cohesion: Results and directions. Comunicação e Sociedade, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchi, G. P., & Vendramini, A. (2021). Dai corpi alle interazioni: La comunità umana in prospettiva dialogica. Padova University Press. Available online: https://www.padovauniversitypress.it/it/publications/9788869382390 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Van Hoey, J., Moret-Tatay, C., Santolaya Prego de Oliver, J. A., & Beneyto-Arrojo, M. J. (2021). Profile changes in male partner abuser after an intervention program in gender-based violence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 65(13–14), 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P., & Garofalo, C. (2015). Personality styles in a non-clinical sample: The role of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 79, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Callea, A., Bucks, R. S., Roberton, T., & Daffern, M. (2017). Exploring anger among offenders: The role of emotion dysregulation and alexithymia. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24(1), 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittgenstein, L. (2009). Philosophical investigations, 4th edition (trans. Hacker and Schulte). Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/witpi (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2022). Violence info—Intimate partner violence. World Health Organization. Available online: http://apps.who.int/violence-info/intimate-partner-violence (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Zeldin, S. (2004). Preventing youth violence through the promotion of community engagement and membership. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Investigation Area | Specific Aim |

|---|---|

| Role of ‘victim’ | To outline how a person who has undergone violence is narrated and talks about themself. |

| Role of ‘offender’ | To outline how a person who perpetrated violence is narrated and talks about themself. |

| Role of ‘Victim’ | Role of ‘Offender’ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRs | dW | DRs | dW | |

| Victims |

| 0.14 |

| 0.13 |

| Offenders |

| 0.1 |

| 0.35 |

| Experts |

| 0.3 |

| 0.66 |

| Victims | Offenders | Experts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forms | χ2 | Forms | χ2 | Forms | χ2 |

| to feel (sentire) | 1.6636 | to have (avere) | 2.8864 | scare (impaurire) | 1.5334 |

| to be (essere) | 1.082 | helpless (impotente) | 0.8882 | ||

| to react (reagire) | 0.7162 | ||||

| to react (reagire) | −0.5127 | helpless (impotente) | −0.2289 | victim (vittima) | −0.5084 |

| helpless (impotente) | −0.6178 | scare (impaurire) | −0.2289 | to be (essere) | −0.8447 |

| scare (impaurire) | −1.1256 | to be (essere) | −0.3852 | to have (avere) | −0.967 |

| to feel (sentire) | −1.2972 | ||||

| Victims | Offenders | Experts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forms | χ2 | Forms | χ2 | Forms | χ2 |

| to be (essere) | 1.2227 | to do (fare) | 0.7909 | to be able (riuscire) | 1.2749 |

| violent (violento) | 0.7909 | unable (incapace) | 0.2959 | ||

| unable (incapace) | 0.2959 | violent (violento) | 0.2959 | ||

| to have (avere) | −0.4284 | to be able (riuscire) | −0.3063 | unable (incapace) | −0.4369 |

| to do (fare) | −0.8835 | to be (essere) | −1.0844 | violent (violento) | −1.1136 |

| to be able (riuscire) | −0.8835 | ||||

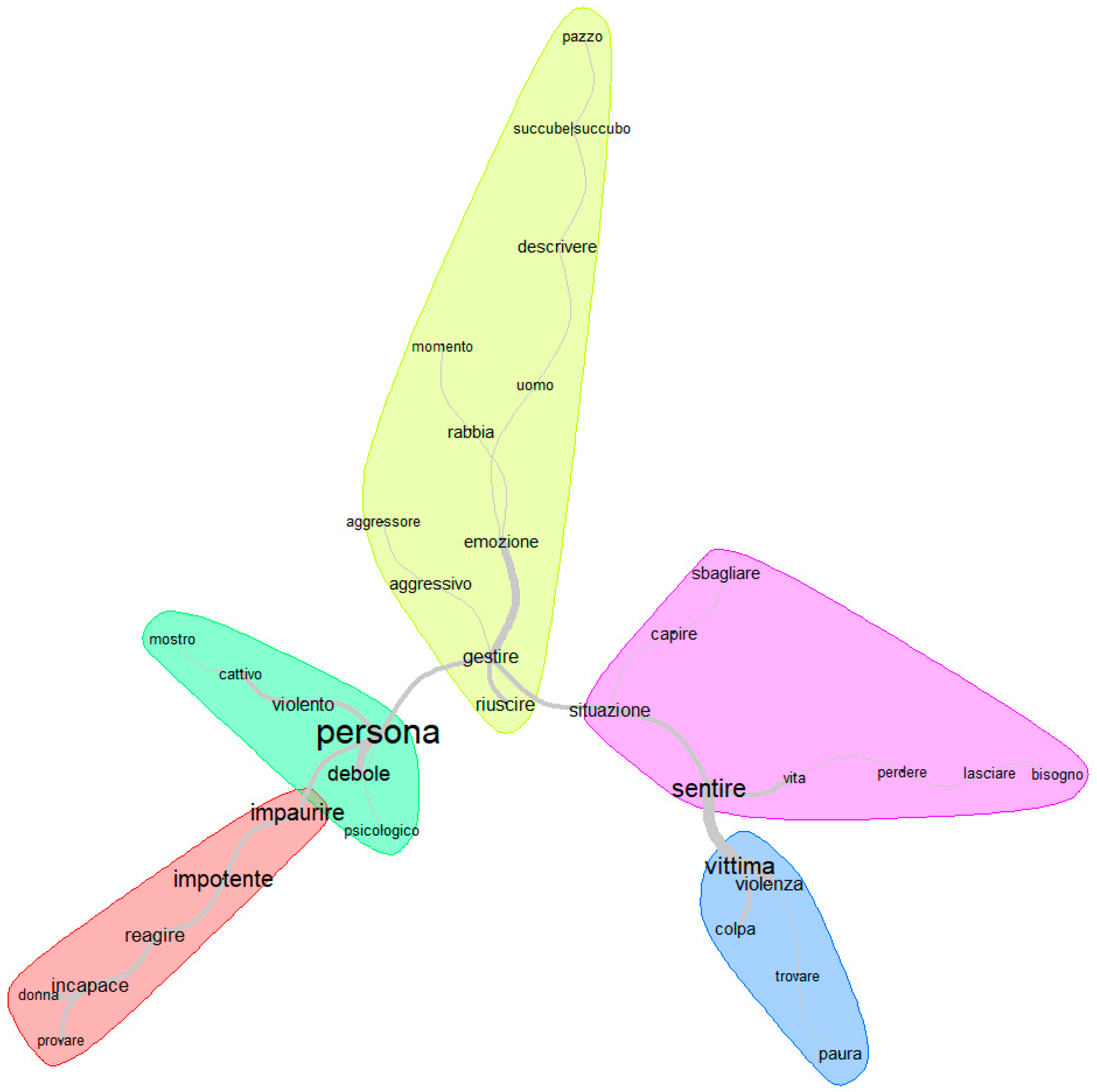

| Cluster 1—Role of ‘Offender’ | Cluster 2—Role of ‘Victim’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Form | ρ | Form | ρ |

| person (persona) | 0.00015 | victim (vittima) | 0.00011 |

| weak (debole) | 0.01735 | to feel (sentire) | 0.00182 |

| violent (violento) | 0.04839 | (to react) reagire | 0.00225 |

| scare (impaurire) * | 0.07226 | (violence) violenza | 0.00225 |

| anger (rabbia) * | 0.08018 | fear (paura) | 0.01430 |

| emotion (emozione) * | 0.08018 | guilt (colpa) | 0.01430 |

| to understand (capire) | 0.01430 | ||

| to find (trovare) | 0.03549 | ||

| helpless (impotente) | 0.03995 | ||

| situation (situazione) * | 0.06937 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moro, C.; Scaccia, M.; Camellini, T.; Lugeri, L.; Marrocu, E.; Turchi, G.P. Stigma and Emotion Regulation in Intimate Partner Violence: A Pilot Exploratory Study with Victims, Offenders and Experts. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091229

Moro C, Scaccia M, Camellini T, Lugeri L, Marrocu E, Turchi GP. Stigma and Emotion Regulation in Intimate Partner Violence: A Pilot Exploratory Study with Victims, Offenders and Experts. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091229

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoro, Christian, Michela Scaccia, Teresa Camellini, Livia Lugeri, Emanuele Marrocu, and Gian Piero Turchi. 2025. "Stigma and Emotion Regulation in Intimate Partner Violence: A Pilot Exploratory Study with Victims, Offenders and Experts" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091229

APA StyleMoro, C., Scaccia, M., Camellini, T., Lugeri, L., Marrocu, E., & Turchi, G. P. (2025). Stigma and Emotion Regulation in Intimate Partner Violence: A Pilot Exploratory Study with Victims, Offenders and Experts. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1229. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091229