University Students’ Good Practices as Moderators Between Active Coping and Stress Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Coping from Transactional and Systemic-Cognitive Perspectives

1.2. Students’ Good Practices in the University Ecosystem

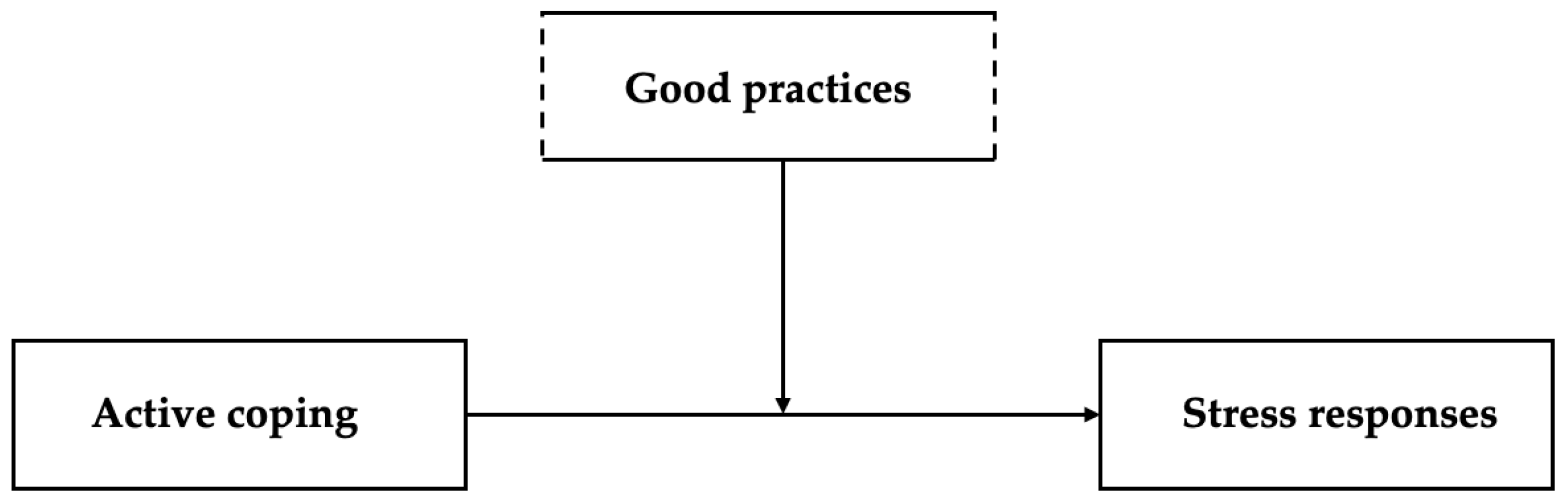

1.3. Articulation Between Good Practices and Coping with Academic Stress

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methodology

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Active Coping

2.2.2. Stress Responses

2.2.3. University Students’ Good Practices

- (a)

- Feedback-Seeking

- (b)

- Cooperative Work

- (c)

- Time Management

- (d)

- Active Learning

2.2.4. Control Variables

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial Analyses

3.2. Regression Analysis with Interaction Effects

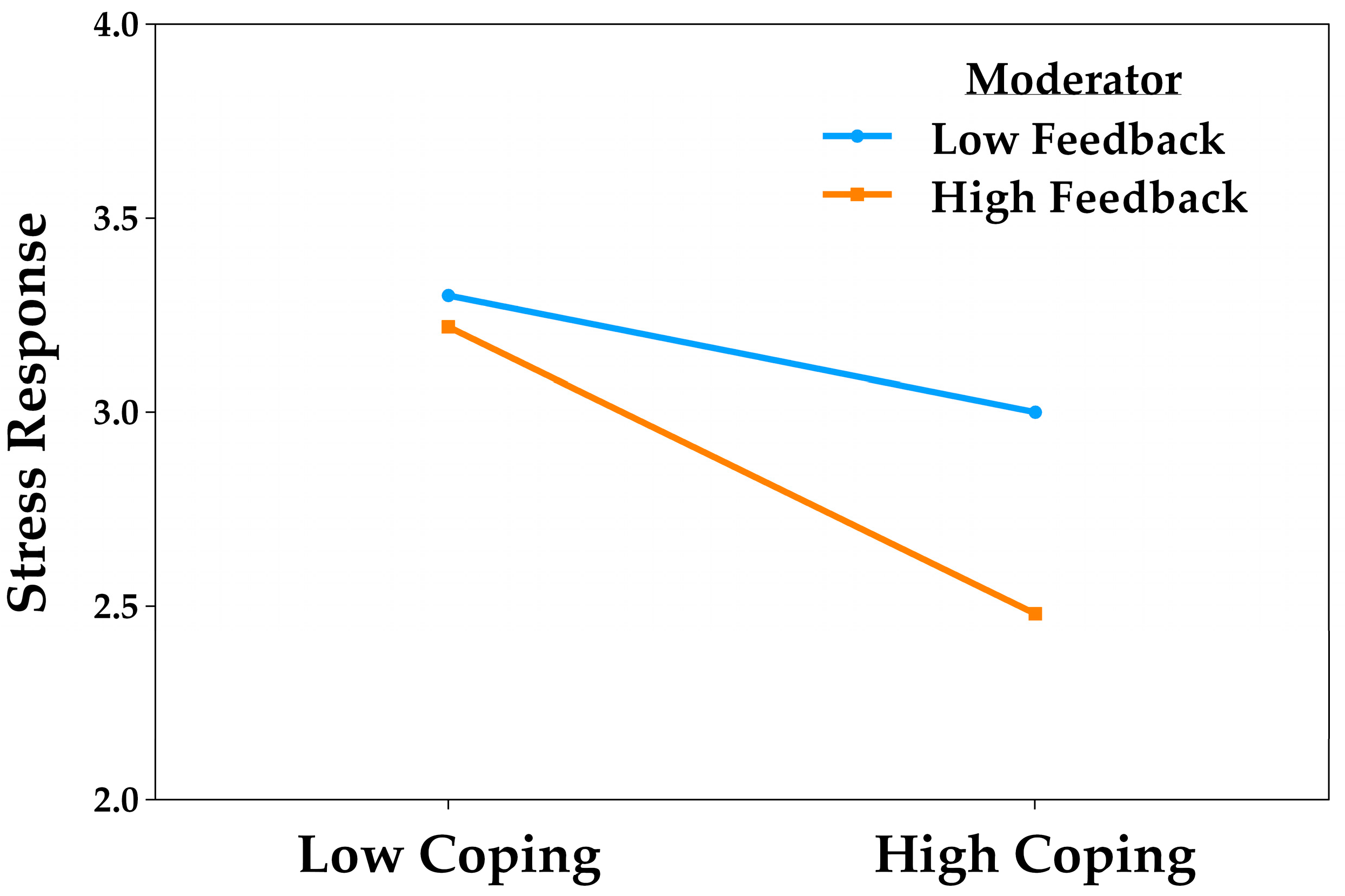

3.2.1. Moderation Analysis One: Feedback-Seeking

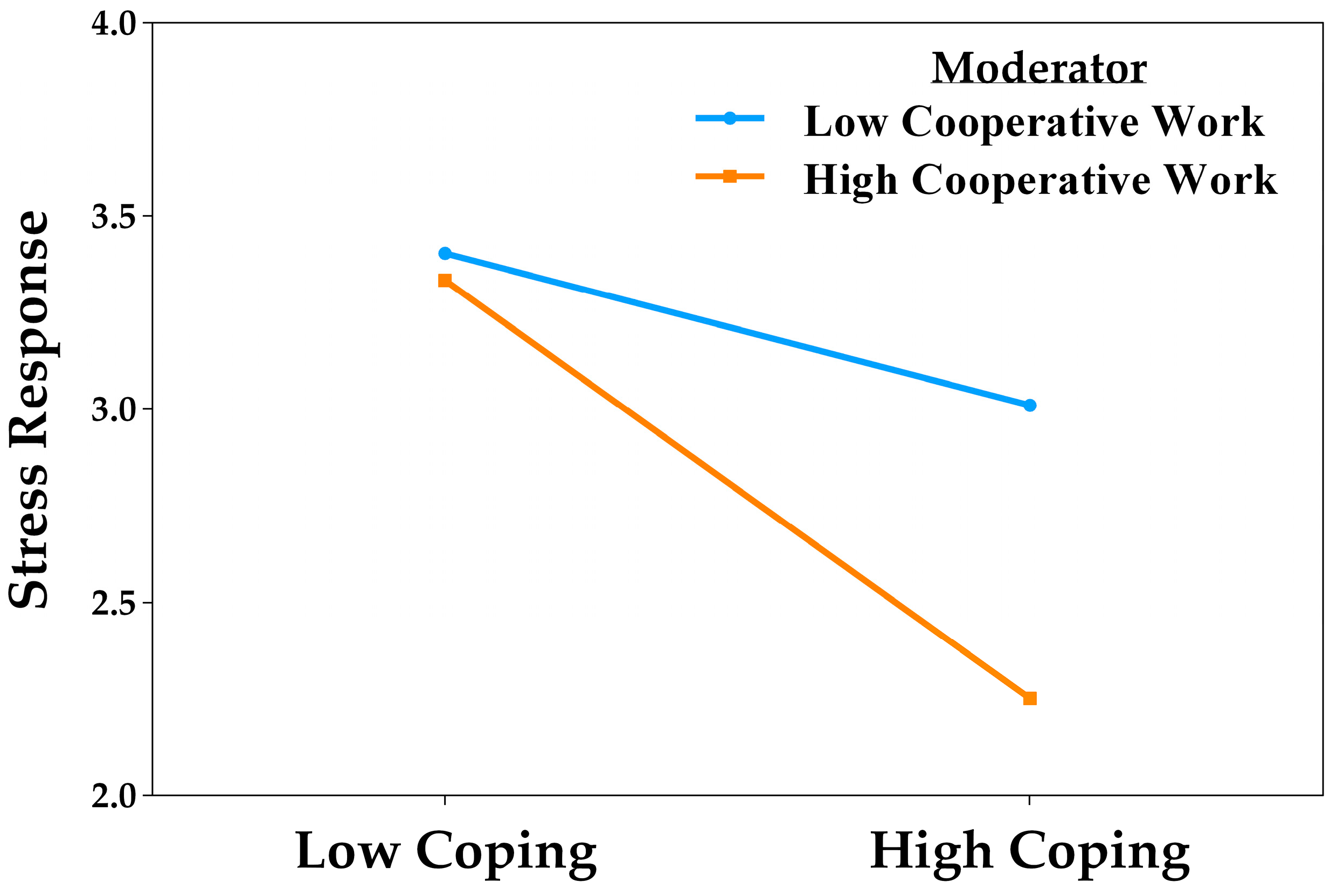

3.2.2. Moderation Analysis Two: Cooperative Work

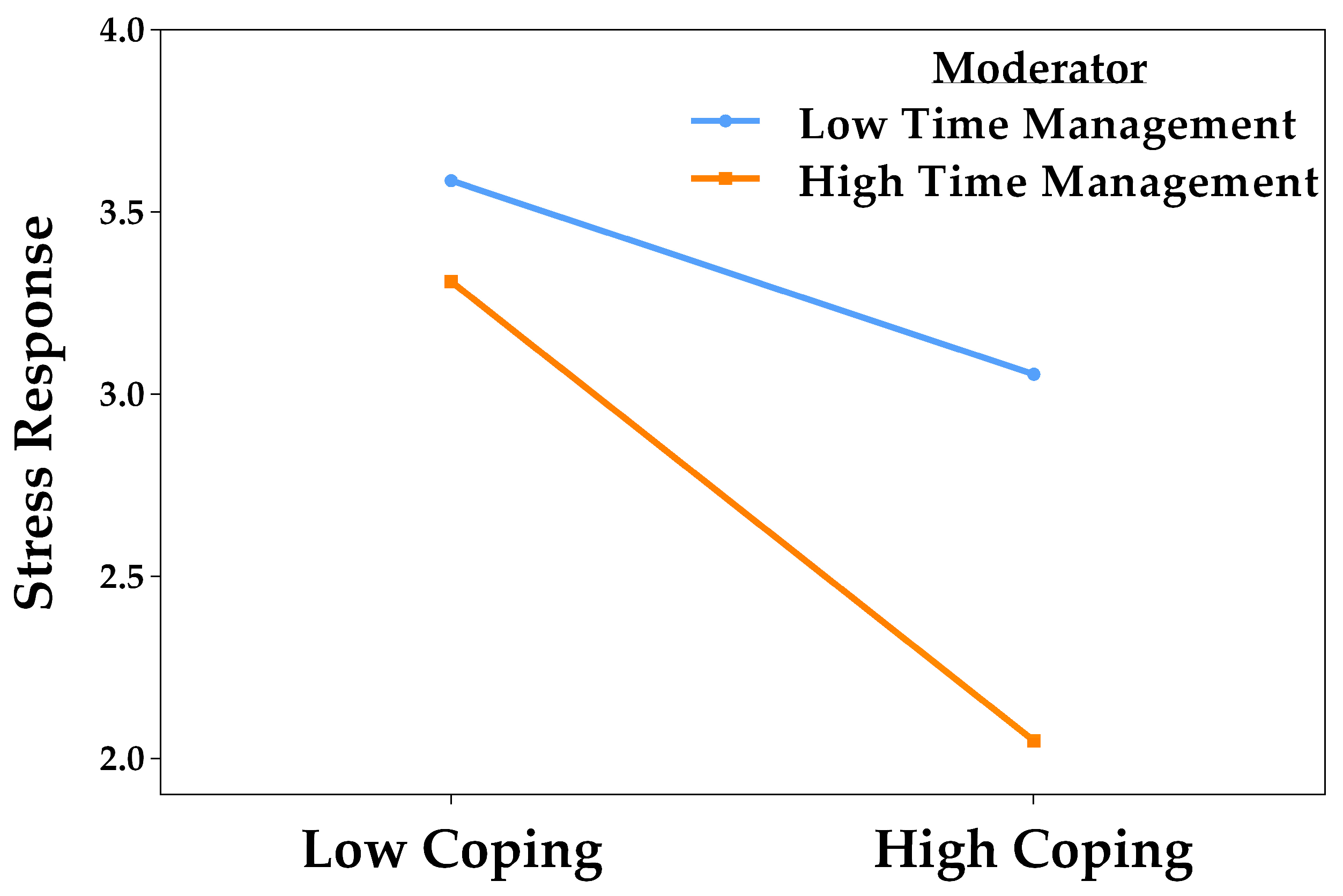

3.2.3. Moderation Analysis Three: Time Management

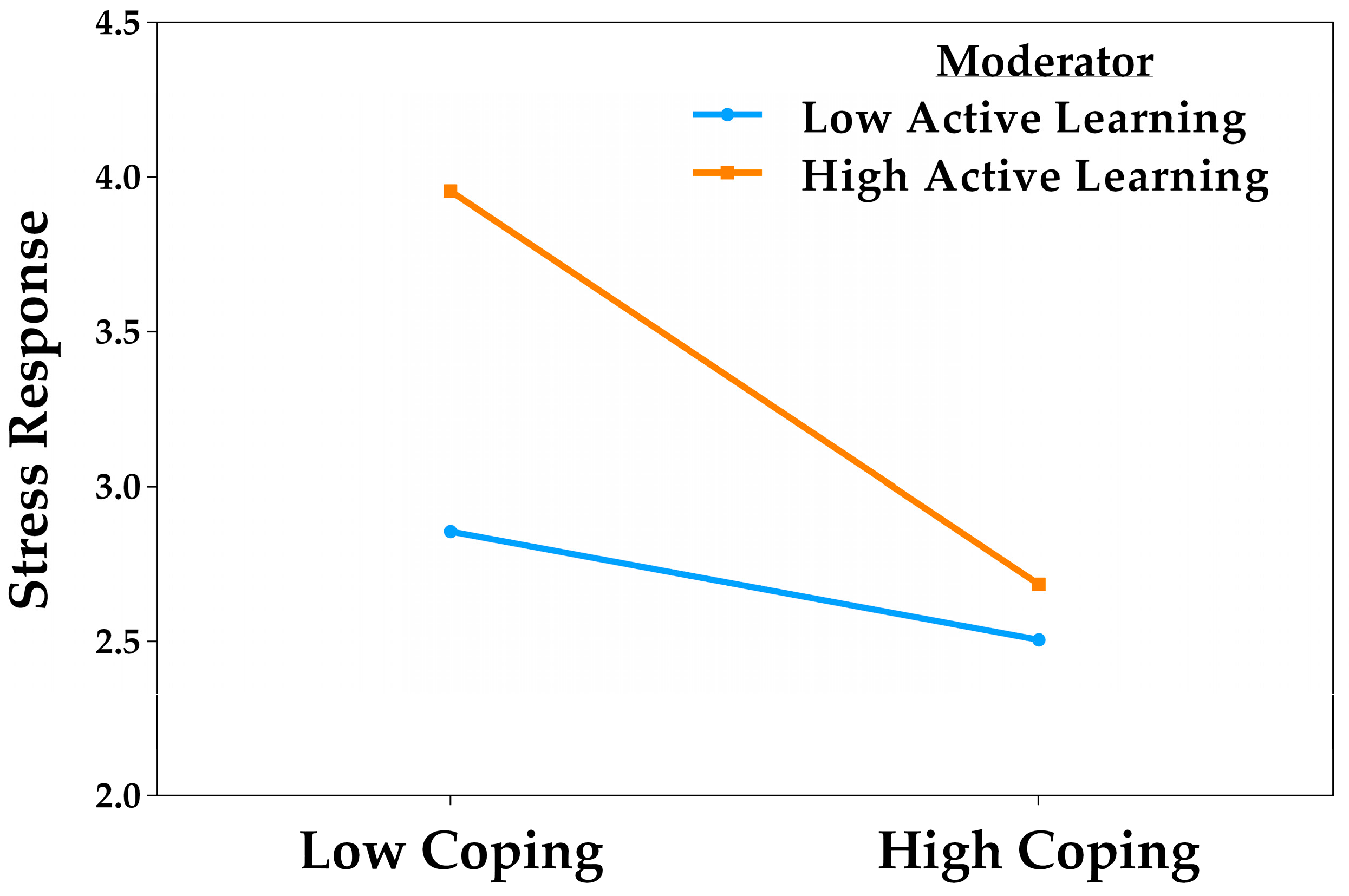

3.2.4. Moderation Analysis Four: Active Learning

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

- (1)

- Low-cost, high-impact transversal measures. From the first semester and throughout the initial stages of university study, it is recommended to implement rubrics with explicit criteria and formative feedback on academic performance, establish virtual forums for timely consultation on tasks and content, and provide targeted short-format workshops on time management (Chust-Hernández et al., 2024). These measures strengthen feedback, peer collaboration, and time management—three practices identified in our study as progressive enhancers of active coping.

- (2)

- Scaffolded pathways for active learning with self-regulatory support. Active methodologies—such as project-based learning or flipped classrooms—can be designed to incorporate structured opportunities for goal setting, periodic self-assessment, and training in coping strategies. These learning environments should progressively scale task complexity and integrate guided regulation tools such as checklists or debriefing sessions (Bingen et al., 2019; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). Such scaffolding is critical, as our study revealed a threshold effect: active learning only reduced stress when combined with high engagement and consolidated self-regulatory skills. At this level, it is also particularly pertinent to integrate well-established cooperative learning models, such as Project-Based Collaborative Learning (PBCL), which effectively combines project-based problem solving with collective group responsibility and shared socio-emotional regulation (Huang et al., 2024). Likewise, cooperative learning strategies and peer tutoring methods (Durán Gisbert et al., 2015) have proven effective in both enhancing academic achievement and fostering socio-emotional competencies.

- (3)

- Institutional policies for academic well-being. At the organizational level, it is important to incorporate indicators of good practices into teaching quality assurance systems—for example, the frequency and perceived usefulness of feedback provided and requested (Khuder, 2025). In addition, systematically assessing these practices among students would allow the identification of profiles of strengths and areas for improvement, offering a dynamic view of how they cope with academic stress. This information could be integrated into tutorial action plans and student support services, facilitating preventive and personalized interventions.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abojedi, A., Alsheikh, A. S., & Basmaji, J. (2023). Assessing the impact of technology use, social engagement, emotional regulation, and sleep quality among undergraduate students in Jordan: Examining the mediating effect of perceived and academic stress. Health Psychology Research, 11, 73348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmady, S., Khajeali, N., Kalantarion, M., Sharifi, F., & Yaseri, M. (2021). Relation between stress, time management, and academic achievement in preclinical medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlHamlan, A. W., AlDhafiri, D. A., AlHajri, N. A., AlHouli, A. H., AlHubaidah, S. M., AlJassar, A. M., AlMutairi, N. N., AlRabiah, A. S., Al-Sultan, A. T., & Qasem, W. (2025). The impact of academic stress on the lifestyle of university students in Kuwait. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College Health Association. (2023). American college health association–National college health assessment III: Undergraduate student reference group data report: Spring 2023. Available online: https://www.acha.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/NCHA-III_SPRING_2023_UNDERGRAD_REFERENCE_GROUP_DATA_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1997). A stitch in time: Self-regulation and proactive coping. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M., López-García, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, L. D., Keer, H. V., & Valcke, M. (2015). Promoting university students metacognitive regulation through peer learning: The potential of reciprocal peer tutoring. Higher Education, 70(3), 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza, A. (2006). Un modelo conceptual para el estudio del estrés académico. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztalaca, 9(3), 110–129. [Google Scholar]

- Barraza, A. (2018). Inventario sistémico cognoscitivista para el estudio del estrés académico. Segunda versión de 21 ítems. Ecorfan. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Agudelo, J. C., Restrepo, D., Navarro-Jimenez, E., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2025). Longitudinal effects of stress in an academic context on psychological well-being, physiological markers, health behaviors, and academic performance in university students. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezie, A. E., Abere, G., Zewude, G. T., Desye, B., Daba, C., Abeje, E. T., & Keleb, A. (2025). Prevalence of stress and associated fac-tors among students in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1518851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingen, H. M., Steindal, S. A., Krumsvik, R., & Tveit, B. (2019). Nursing students studying physiology within a flipped classroom, self regulation and off campus activities. Nurse Education in Practice, 35, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bintz, G., Barenberg, J., & Dutke, S. (2024). Components of the flipped classroom in higher education: Disentangling flipping and enrichment. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1412683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigati, J. R., England, B. J., & Schussler, E. E. (2020). How do undergraduates cope with anxiety resulting from active learning practices in introductory biology? PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0236558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulfone, G., Ingravalle, F., Scerbo, F., Mazzotta, R., Simonelli, I., Pancaldi, A., Ungaro, S., Cocco, M., Vellone, E., Alvaro, R., Vinci, A., & Maurici, M. (2025). Substance use and academic performance among university students: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanach, R., Valle, A., Rodríguez, S., & Piñeiro, I. (2008, April 23–25). Respuesta de estrés en contextos universitarios: Construcción de una escala de medida [Conference presentation]. V Congreso Internacional de Psicología y Educación, Oviedo, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanach, R. G., Valle, A., Rodríguez, S., Piñeiro, I., & Freire, C. (2010). Escala de Afrontamiento del Estrés Académico (A-CEA). Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 1(1), 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Song, J., Li, M., He, H., Wang, X., Zhou, S., & Wang, L. (2025). Integrating jigsaw teaching into self-regulated learning instruction: An instructional design to improve nursing students’ self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1437265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chickering, A. W., & Schlossberg, N. K. (1995). Getting the most out of college. Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Chust-Hernández, P., López González, E., & Senent Sánchez, J. M. (2024). Intervención en habilidades de estudio sobre el estrés y la autoeficacia académicos en universitarios de nuevo ingreso. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 22(64), 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K. M., Downing, V. R., & Brownell, S. E. (2018). The influence of active learning practices on student anxiety in large-enrollment college science classrooms. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente, J., Amate, J., González-Torres, M. C., Artuch, R., García-Torrecillas, J. M., & Fadda, S. (2020). Effects of levels of self-regulation and regulatory teaching on strategies for coping with academic stress in undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente-Arias, J. (2017). Theory of self- vs. externally-regulated learning: Fundamentals, evidence, and applicability. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diningrat, S. W. M., Marín, V. I., & Bachri, B. S. (2024). Students’ self regulated learning strategies in the online flipped classroom. Journal of Educators Online, 21(3), n3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Gisbert, D., Flores Coll, M., Mosca, A., & Santiviago, C. (2015). Tutorías entre iguales: Del concepto a la práctica en las diferentes etapas educativas. InterCambios: Dilemas y Transiciones de la Educación Superior, 2(1), 28–39. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5436829 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- England, B. J., Brigati, J. R., Schussler, E. E., & Chen, M. M. (2019). Student anxiety and perception of difficulty impact performance and persistence in introductory biology courses. CBE Life Sciences Education, 18(2), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraile, J., Gil Izquierdo, M., & Medina Moral, E. (2023). The impact of rubrics and scripts on self regulation, self efficacy and performance in collaborative problem-solving tasks. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(8), 1223–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C., Ferradás, M. D. M., Regueiro, B., Rodríguez, S., Valle, A., & Núñez, J. C. (2020). Coping strategies and self-efficacy in university students: A person-centered approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, X., Zhong, H., Chen, J., Fei, H., Yao, Y., Xiao, Y., Li, W., & Li, N. (2025). Unlocking academic success: The impact of time management on college students’ study engagement. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Cabanach, R., Souto-Gestal, A., González-Doniz, L., & Franco Taboada, V. (2018). Perfiles de afrontamiento y estrés académico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 36(2), 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozalo Delgado, M., Gonzaga, L., Pinheiro, M. R., & León del Barco, B. (2012). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del inventario de buenas prácticas en estudiantes universitarios. In En VII congresso ibero americano de docência universitária (pp. 221–237). CIIE. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.15/1360 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Gozalo Delgado, M., & León del Barco, B. (2014). Propiedades psicométricas de los inventarios TCC y GRPS del inventario de buenas prácticas en universitarios. Revista INFAD de psicología. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 2(1), 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gozalo Delgado, M., León del Barco, B., & Romero Moncayo, M. (2022). Buenas prácticas del estudiante universitario que predicen su rendimiento académico. Educación XX1, 25(1), 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greisel, M., Spang, L., Fett, K., & Kollar, I. (2024). Problem perception and problem regulation during online collaborative learning: What is important for successful collaboration? Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1351723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón, C., Batalla Flores, A., & Esteban Bara, F. (2019a). Role of coping responses in the relationship between perceived stress and psychological well being in a sample of Spanish educational teacher students. Psychological Reports, 122(2), 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón, C., & Calderón-Garrido, D. (2019b). Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education students. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., Dawson, P., Phillips, M., Molloy, E., & Mahoney, P. (2021). The usefulness of feedback. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(3), 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Wei, J., Wang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2024). Regulation of emotions in project-based collaborative learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1368196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, B., Saab, N., van den Broek, P., & van Driel, J. (2019). The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(6), 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, K., & Halcomb-Smith, L. (2020). Innovation, critical pedagogy, and appreciative feedback: A model for practitioners. In S. Palahicky (Ed.), Enhancing learning design for innovative teaching in higher education (pp. 1–21). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirjees, F., Odeh, M., Al-Haddad, A., Ass’ad, R., Hassanin, Y., Al-Obaidi, H., Kharaba, Z., Alfoteih, Y., & Alzoubi, K. H. (2024). Test anxiety and coping strategies among university students an exploratory study in the UAE. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 25835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphle, M., Karki, R., Khanal, S., Aryal, D., & Adhikari, K. (2024). Assessment of academic stress and its association with academic achievement among health science students. Archives of Mental Health, 25(2), 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuder, B. (2025). Feedback-seeking behaviour as a self-regulation strategy in higher education: A pedagogical approach. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 50(6), 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F., & Han, Y. (2024). The influences of international master’s students’ feedback seeking behaviour on their feedback literacy and feedback contexts: An ecological perspective. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 71, 101424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10 year population level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Ye, Y. (2025). Exploring how group cooperative learning affect college students’ online self regulated learning: The important role of socially shared regulation, perceived task value, and teacher support. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 40(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, F. J. (2004). El estrés académico: Problemas y soluciones desde una perspectiva psicosocial. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N., Oberhoffer-Fritz, R., Reiner, B., & Schulz, T. (2025). Stress, student burnout and study engagement—A cross-sectional comparison of university students of different academic subjects. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzak, A., Zhang, X., & Vytasek, J. (2025). Boosting productivity and wellbeing through time management: Evidence-based strategies for higher education and workforce development. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1623228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M., Braakhekke, E., Kesselring, M., Wijsbroek, S., Schramel, I., Putter, I., Erik, K., Juliette, G., Nely, S., Sharon, W., & Marloes, K. (2025). Understanding and tackling academic stress and school attendance problems within the school system: A co-creation approach. Mental Health & Prevention, 37, 200388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, M. R. (2008). Princípios e desafios para boas práticas dos estudantes no ensino superior: Uma proposta de operacionalização. In En actas do I congresso resapes (pp. 219–232). Universidade de Aveiro. [Google Scholar]

- Román, C. A., & Hernández, Y. (2011). El estrés académico: Una revisión crítica del concepto desde las ciencias de la educación. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 14(2), 1–14. Available online: https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/repi/article/view/26023 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Sáenz, C., Boldú, E., & Canal, J. (2025). Health promoting universities: A scoping review. Health Promotion Journal of Australia: Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals, 36(2), e939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossberg, N. K., Waters, E. B., & Goodman, J. (1995). Counseling adults in transition: Linking practice with theory (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Valdivieso-León, L., Lucas Mangas, S., Tous-Pallarés, J., & Espinoza-Díaz, I. M. (2020). Coping strategies for academic stress in undergraduate students: Early childhood and primary education. Educación XX1, 23(2), 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, M. J., & Roseth, C. J. (2021). The cascading effects of reducing student stress: Cooperative learning as a means to reduce emotional problems and promote academic engagement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 41(5), 700–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q., Zhao, H., Fan, J., & Li, J. (2022). Effects of flipped classroom on nursing psychomotor skill instruction for active and passive learners: A mixed methods study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 39, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. K., & Lai, W. H. (2025). Association between time management practices and perceived stress levels in preclinical chiropractic students. The Journal of Chiropractic Education, 39, eJCE-24-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J. W. (2018). Testing the three-way interaction effect of academic stress, academic self-efficacy, and task value on persistence in learning among Korean college students. Higher Education, 76(5), 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S., & Carless, D. (2024). Investigating variation in undergraduate students’ feedback seeking experiences: Towards the integration of feedback seeking within the curriculum. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(8), 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M (SD) | R-CEA | A-CEA | FS | CW | TM | AL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-CEA | 2.57 (0.74) | 1 | |||||

| A-CEA | 2.82 (0.47) | −0.27 ** | 1 | ||||

| FS | 2.44 (0.73) | −0.27 ** | 0.07 * | 1 | |||

| CW | 3.62 (0.55) | −0.36 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.06 | 1 | ||

| TM | 4.01 (0.56) | −0.41 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.01 | 0.19 ** | 1 | |

| AL | 2.94 (0.63) | 0.23 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.02 | 0.34 ** | 0.33 ** | 1 |

| Variables | B (SE) | Beta | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.22 (0.05) | 0.14 | 4.76 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.000 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| A-CEA | −0.26 (0.11) | −0.17 | −2.44 | 0.015 | −0.48 | −0.04 |

| FS | −0.15 (0.07) | −0.15 | −2.33 | 0.020 | −0.23 | −0.01 |

| A-CEA × FS | −0.11 (0.05) | −0.38 | −2.15 | 0.032 | −0.21 | −0.01 |

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R2 (%) | 19.7 | |||||

| Model | F(1008, 1013) = 21.72, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Assumptions | ||||||

| Normality | p = 0.258 | |||||

| Independence | 2.04 | |||||

| Homocedasticicy | p = 0.721 | |||||

| Variables | B (SE) | Beta | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.22 (0.05) | 0.14 | 4.66 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.000 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| A-CEA | −0.37 (0.13) | −0.23 | −2.83 | 0.005 | −0.63 | −0.11 |

| CW | −0.21 (0.08) | −0.15 | −2.52 | 0.012 | −0.37 | −0.05 |

| A-CEA × CW | −0.17 (0.08) | −0.60 | −2.08 | 0.038 | −0.33 | −0.01 |

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R2 (%) | 18.5 | |||||

| Model | F(1008, 1013) = 21.22, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Assumptions | ||||||

| Normality | p = 0.200 | |||||

| Independence | 2.08 | |||||

| Homocedasticicy | p = 0.398 | |||||

| Variables | B (SE) | Beta | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.27 (0.05) | 0.17 | 5.66 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.37 |

| Age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.868 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| A-CEA | −0.45 (0.14) | −0.28 | −3.11 | 0.002 | −0.72 | −0.18 |

| TM | −0.32 (0.12) | −0.24 | −2.65 | 0.008 | −0.56 | −0.08 |

| A-CEA × TM | −0.18 (0.08) | −0.67 | −2.23 | 0.026 | −0.34 | −0.02 |

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R2 (%) | 21.6 | |||||

| Model | F(1008, 1013) = 26.43, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Assumptions | ||||||

| Normality | p = 0.207 | |||||

| Independence | 1.99 | |||||

| Homocedasticicy | p = 0.537 | |||||

| Variables | B (SE) | Beta | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.21 (0.05) | 0.14 | 4.57 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.31 |

| Age | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.868 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| A-CEA | −0.41 (0.11) | −0.26 | −3.65 | <0.001 | −0.63 | −0.19 |

| AL | 0.32 (0.11) | 0.27 | 3.05 | 0.002 | 0.10 | 0.53 |

| A-CEA × AL | −0.23 (0.10) | −0.78 | −2.35 | 0.019 | −0.43 | −0.03 |

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R2 (%) | 23.1 | |||||

| Model | F(1008, 1013) = 22.55, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Assumptions | ||||||

| Normality | p = 0.200 | |||||

| Independence | 1.98 | |||||

| Homocedasticicy | p = 0.641 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Camacho, C.; Gozalo, M.; Felipe-Castaño, E. University Students’ Good Practices as Moderators Between Active Coping and Stress Responses. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091223

Ruiz-Camacho C, Gozalo M, Felipe-Castaño E. University Students’ Good Practices as Moderators Between Active Coping and Stress Responses. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091223

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Camacho, Cristina, Margarita Gozalo, and Elena Felipe-Castaño. 2025. "University Students’ Good Practices as Moderators Between Active Coping and Stress Responses" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091223

APA StyleRuiz-Camacho, C., Gozalo, M., & Felipe-Castaño, E. (2025). University Students’ Good Practices as Moderators Between Active Coping and Stress Responses. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091223