Am I (Not) Perfect? Fear of Failure Mediates the Link Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perfectionism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perfectionism and Narcissism

1.2. Perfectionism and Fear of Failure

1.3. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Materials and Measures

2.3.1. Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism

2.3.2. Perfectionism

2.3.3. Fear of Failure

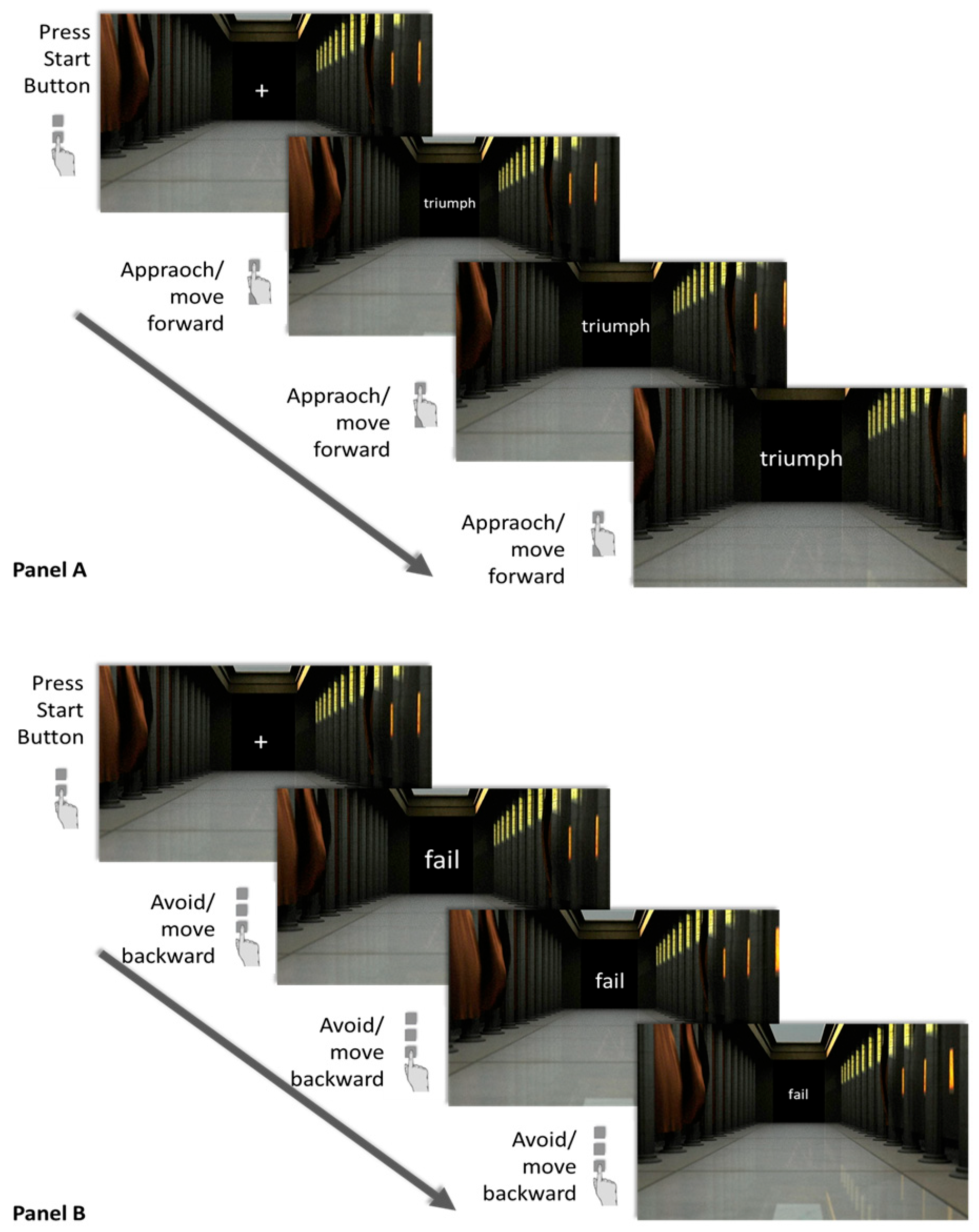

2.3.4. Failure Avoidance

2.4. Data Preprocessing and Statistical Analyses

2.5. Power Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Distinction of GN and VN Based on Their Relationships to Perfectionism

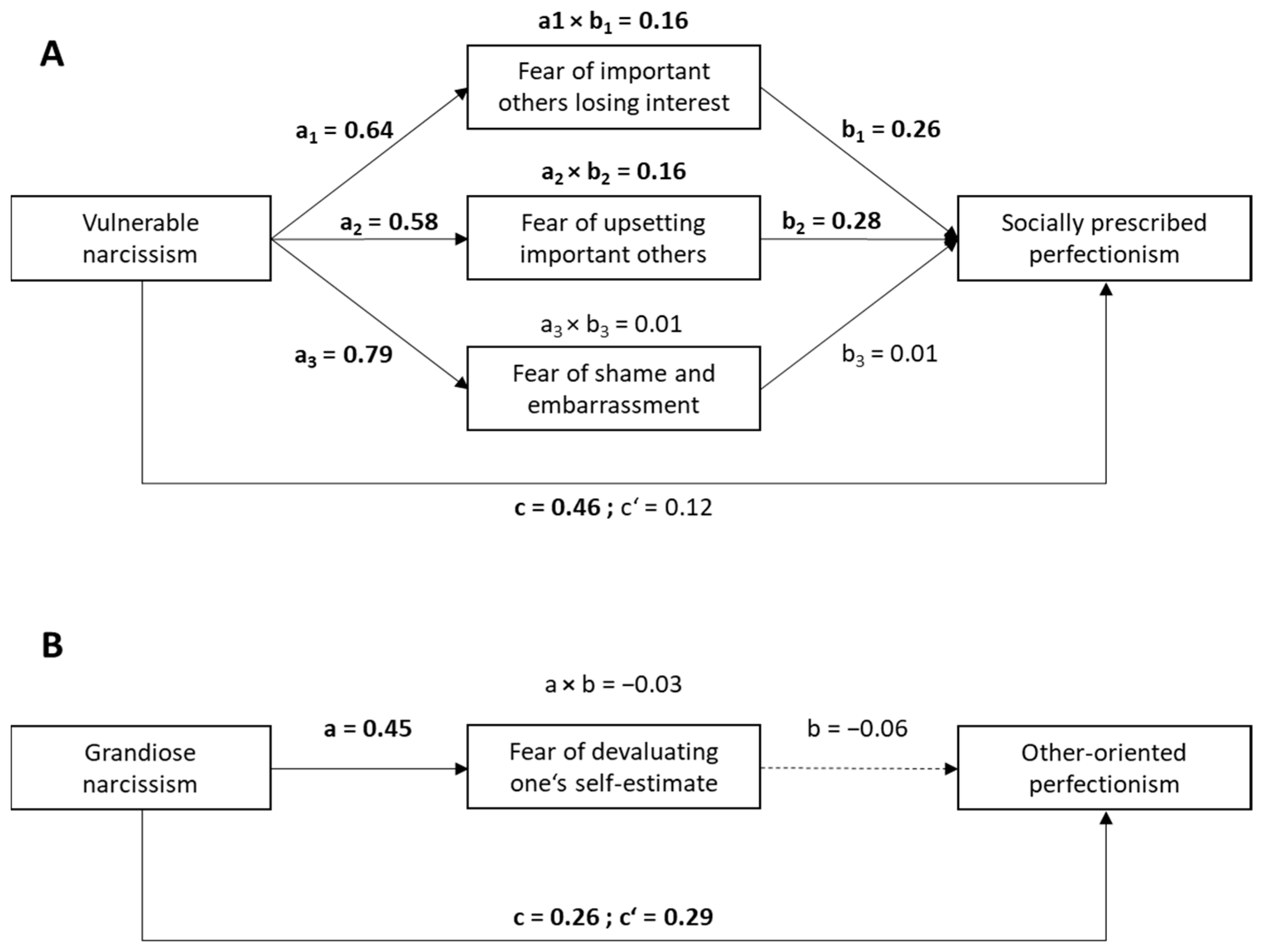

3.2. Grandiose Narcissism, Perfectionism, and Fear of Failure

3.3. Narcissism, Fear of Failure, and Implicit Failure Avoidance

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Summary and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Please note that with regard to Hypothesis 1 (H1), only FIOLI and FUIO were included in the initial preregistration. Because some research indicates FSE as the most critical fear in the context of perfectionism (e.g., Sagar et al., 2010), we expanded H1 by FSE as a third supposed mediator. |

| 2 | Word frequency was determined for each word using a lexical corpus of the (Leipzig Corpora Collection, 2011). Hereby, frequency information is based on the word list of the largest corpus available in the German language. |

| 3 | The appropriateness of one-sided tests—even in the event of directional hypotheses—is a matter of debate (e.g., Greenland et al., 2016; Ruxton & Neuhäuser, 2010). Some researchers recommend defaulting to two-sided tests as a more conservative way of hypothesis testing that preserves the ability to detect unexpected results (e.g., see Ruxton & Neuhäuser, 2010). |

| 4 | Differences in sample sizes required for the different mediation models result from differences in effect sizes, i.e., the size of bivariate correlations between predictor (GN, VN), outcome (types of perfectionism), and the respective mediator considered in the model. Estimates for these bivariate correlations were extracted from the literature (Conroy et al., 2007; Henschel & Iffland, 2021; Smith et al., 2016). A screenshot with the relevant input parameters used in these power analyses is provided at https://osf.io/w2459/?view_only=4f728d97bed94a2db4c7d5f900391fde (accessed on 1 September 2025). The shiny app was accessed through https://schoemanna.shinyapps.io/mc_power_med/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). |

References

- Abbasi, N. u. H., Arshad, Q., Wang, T., & Hadi, A. (2024). Narcissism, perfectionism, and self-promoting behavior on social networking sites among university students in Pakistan. Anales de Psicología, 40(2), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altstötter-Gleich, C. (2018). German translation of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) [Unpublished questionnaire]. University of Koblenz-Landau.

- Aubé, B., Rougier, M., Muller, D., Ric, F., & Yzerbyt, V. (2019). The online-VAAST: A short and online tool to measure spontaneous approach and avoidance tendencies. Acta Psychologica, 201, 102942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: Emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(8), 874–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 638–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casale, S., Svicher, A., Fioravanti, G., Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Pozza, A. (2024). Perfectionistic self-presentation and psychopathology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 31(2), e2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chęć, M., Konieczny, K., Michałowska, S., & Rachubińska, K. (2025). Exploring the dimensions of perfectionism in adolescence: A multi-method study on mental health and CBT-based psychoeducation. Brain Sciences, 15(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, B., Landmann, S., Külz, A.-K., Takano, K., Moritz, S., & Jelinek, L. (2022). Direct and indirect assessment of perfectionism in patients with depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder (A. Weizman, Ed.). PLoS ONE, 17(10), e0270184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, V., O’Selmo, E., & Whitehead, P. (2020). Stress, psychological distress, burnout and perfectionism in UK dental students. British Dental Journal, 229(9), 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D. E. (2001). Progress in the development of a multidimensional measure of fear of failure: The performance failure appraisal inventory (pfai). Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 14(4), 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D. E., Kaye, M., & Fifer, A. (2007). Cognitive links between fear of failure and perfectionism. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 25, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D. E., Willow, J. P., & Metzler, J. N. (2002). Multidimensional fear of failure measurement: The performance failure appraisal inventory. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(2), 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J., King, K., & Inzlicht, M. (2020). Why are self-report and behavioral measures weakly correlated? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, C., & Stelmack, R. M. (1997). Movement time differentiates extraverts from introverts. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(5), 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, C., & Stelmack, R. M. (2000). An event-related potential analysis of extraversion and individual differences in cognitive processing speed and response execution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, R., & De Caluwé, E. (2024). Individual differences in the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in higher education in terms of burnout, generalized anxiety, and fear of failure. Acta Psychologica, 249, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2001). Achievement goals and the hierarchical model of achievement motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A. H., & Vaillancourt, T. (2019). Developmental pathways of perfectionism: Associations with bullying perpetration, peer victimization, and narcissism. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 65, 101065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Blankstein, K., & O’Brien, S. (1991). Perfectionism and learned resourcefulness in depression and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(1), 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., & Nepon, T. (2014). Understanding the narcissistic perfectionists among us: Grandiosity, vulnerability, and the quest for the perfect self. In A. Besser (Ed.), Handbook of the psychology of narcissism (pp. 43–66). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, R. O., Heimberg, R. G., Holt, C. S., Mattia, J. I., & Neubauer, A. L. (1993). A comparison of two measures of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14(1), 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14(5), 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2020). The “why” and “how” of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S., Senn, S. J., Rothman, K. J., Carlin, J. B., Poole, C., Goodman, S. N., & Altman, D. G. (2016). Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, C., Powell, G., & Sumner, P. (2018). The reliability paradox: Why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behavior Research Methods, 50(3), 1166–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschel, C., & Iffland, B. (2021). Measuring fear of failure: Validation of a German version of the Performance Failure Appraisal Inventory. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 2(1), 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1990). Perfectionism and depression: A multidimensional analysis. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 5(5), 423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Habke, M., Parkin, M., Lam, R. W., McMurtry, B., Ediger, E., Fairlie, P., & Stein, M. B. (2003). The interpersonal expression of perfection: Perfectionistic self-presentation and psychological distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1303–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Turnbull-Donovan, W., & Mikail, S. (1991). The multidimensional perfectionism scale: Reliability, validity, and psychometric properties in psychiatric samples. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. P., Hall, H. K., & Appleton, P. R. (2010). A comparative examination of the correlates of self-oriented perfectionism and conscientious achievement striving in male cricket academy players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(2), 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. W., Zrull, M. C., & Turlington, S. (1997). Perfectionism and interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69(1), 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juwono, I. D., Kun, B., Demetrovics, Z., & Urbán, R. (2023). Healthy and unhealthy dimensions of perfectionism: Perfectionism and mental health in Hungarian adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(5), 3017–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, S. B., Weiss, B., Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2020). Clinical correlates of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism: A personality perspective. Journal of Personality Disorders, 34(1), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A. M., Becker, E. S., & Rinck, M. (2011). Approach and avoidance tendencies in spider fearful children: The Approach-Avoidance Task. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(2), 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieglmeyer, R., & Deutsch, R. (2010). Comparing measures of approach–avoidance behaviour: The manikin task vs. two versions of the joystick task. Cognition & Emotion, 24(5), 810–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. R. X. E., Ishak, Z., Talib, M. A., Ho, Y. M., Prihadi, K. D., & Aziz, A. (2024). Fear of failure among perfectionist students. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 13(2), 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipzig Corpora Collection. (2011). deu_mixed_2011_dan [data set]. Available online: https://corpora.uni-leipzig.de?corpusId=deu_mixed_2011_dan (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Longo, P., Bevione, F., Amodeo, L., Martini, M., Panero, M., & Abbate-Daga, G. (2024). Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa: Associations with clinical picture and personality traits. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 31(1), e2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A., & Opariuc-Dan, C. (2023). Perfect people, happier lives? When the quest for perfection compromises happiness: The roles played by substance use and internet addiction. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1234164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maples, S. T., Neumann, C. S., & Kaufman, S. B. (2025). Profiling narcissism: Evidence for grandiose-vulnerable and other subtypes. Journal of Research in Personality, 115, 104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Back, M. D., Lynam, D. R., & Wright, A. G. C. (2021). Narcissism today: What we know and what we need to learn. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 76(3), 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Keith Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis: Variants of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in Narcissism. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Vize, C., Crowe, M., Sleep, C., Maples-Keller, J. L., Few, L. R., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Vulnerable narcissism is (mostly) a disorder of neuroticism. Journal of Personality, 86(2), 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., McCain, J., Lynam, D. R., Few, L. R., Gentile, B., MacKillop, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2014). A comparison of the criterion validity of popular measures of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder via the use of expert ratings. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morf, C. C., Schürch, E., Küfner, A., Siegrist, P., Vater, A., Back, M., Mestel, R., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2017). Expanding the nomological net of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory: German validation and extension in a clinical inpatient sample. Assessment, 24(4), 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, M., & Dunkley, D. M. (2015). Self-critical perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Low self-esteem and experiential avoidance as mediators. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, S., Kuckertz, J. M., & Amir, N. (2010). Automatic avoidance tendencies in individuals with contamination-related obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(10), 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2000). Academic procrastinators and perfectionistic tendencies among graduate students. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 15(5), 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaf, R. H., Mohr, S. E., Rotteveel, M., & Wicherts, J. M. (2014). Approach, avoidance, and affect: A meta-analysis of approach-avoidance tendencies in manual reaction time tasks. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G. C., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A. L., & Lukowitsky, M. R. (2010). Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redden, S. A., Mueller, N. E., & Cougle, J. R. (2023). The impact of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in perfectionism. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 27(1), 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinck, M., & Becker, E. S. (2007). Approach and avoidance in fear of spiders. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 38(2), 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, A., Moscardini, E., Tucker, R., & Calamia, M. (2022). Perfectionistic self-presentation, socially prescribed perfectionism, self-oriented perfectionism, interpersonal hopelessness, and suicidal ideation in U.S. adults: Reexamining the social disconnection model. Archives of Suicide Research, 26(3), 1447–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rougier, M., Muller, D., Ric, F., Alexopoulos, T., Batailler, C., Smeding, A., & Aubé, B. (2018). A new look at sensorimotor aspects in approach/avoidance tendencies: The role of visual whole-body movement information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruxton, G. D., & Neuhäuser, M. (2010). When should we use one-tailed hypothesis testing? Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 1, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S. S., Busch, B. K., & Jowett, S. (2010). Success and failure, fear of failure, and coping responses of adolescent academy football players. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(2), 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S. S., & Stoeber, J. (2009). Perfectionism, fear of failure, and affective responses to success and failure: The central role of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(5), 602–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S., Hofmann, M. J., & Mokros, A. (2025). Psychopathic personality traits are associated with experimentally induced approach and appraisal of fear-evoking stimuli indicating fear enjoyment. Scientific Reports, 15, 8646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F. D., & Perugini, M. (2013). At what sample size do correlations stabilize? Journal of Research in Personality, 47(5), 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, B. M., Rose, L., Ghosh, A., Phillips, N. L., Lynam, D. R., & Miller, J. D. (2025). Comparison of self-report data validity in undergraduate samples using remote versus in-person administration methods. Psychological Assessment, 37(5), 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, S. B., Gralnick, T. M., Hewitt, P. L., Sherry, D. L., & Flett, G. L. (2014). Perfectionism and narcissism: Testing unique relationships and gender differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 61–62, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P. D., Salanga, M. G. C., & Aruta, J. J. B. R. (2025). The distinct link of perfectionism with positive and negative mental health outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1492466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, P. D., & Owens, R. G. (1998). A dual process model of perfectionism based on reinforcement theory. Behavior Modification, 22(3), 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2016). Perfectionism and narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Research in Personality, 64, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Ge, S. Y. J., Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Baggley, D. L. (2022). Multidimensional perfectionism turns 30: A review of known knowns and known unknowns. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 63(1), 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommantico, M., Postiglione, J., Fenizia, E., & Parrello, S. (2024). Procrastination, perfectionism, narcissistic vulnerability, and psychological well-being in young adults: An Italian study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, E., & Malek, S. (2019). Perfectionism moderates the relationship between thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in adolescents. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90(4), 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeber, J. (2015). How other-oriented perfectionism differs from self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism: Further findings. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(4), 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J. (2018). Comparing two short forms of the Hewitt–Flett Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. Assessment, 25(5), 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J., Sherry, S. B., & Nealis, L. J. (2015). Multidimensional perfectionism and narcissism: Grandiose or vulnerable? Personality and Individual Differences, 80, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, J., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Pietrowsky, R. (2022). Multidimensional perfectionism and the ICD-11 personality disorder model. Personality and Individual Differences, 188, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struijs, S. Y., Lamers, F., Vroling, M. S., Roelofs, K., Spinhoven, P., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2017). Approach and avoidance tendencies in depression and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research, 256, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, M., Vacca, M., Dentale, F., Spagnolo, G., Lombardo, C., Geukes, K., & Back, M. D. (2023). Prospective associations between grandiose narcissism and perfectionism: A longitudinal study in adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 41(2), 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visvalingam, S., Magson, N. R., Newins, A. R., & Norberg, M. M. (2024). Going it alone: Examining interpersonal sensitivity and hostility as mediators of the link between perfectionism and social disconnection. Journal of Personality, 92(4), 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Distinguishing between grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality disorder. In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), Handbook of trait narcissism (pp. 3–13). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(4), 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A., Lukowitsky, M., Pincus, A., & Conroy, D. (2010). The higher order factor structure and gender invariance of the pathological narcissism inventory. Assessment, 17, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosopov, L., Saklofske, D. H., Smith, M. M., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2024). Failure sensitivity in perfectionism and procrastination: Fear of failure and overgeneralization of failure as mediators of traits and cognitions. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 42(6), 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | M | SD | α | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) PNI-GN | 3.33 | 0.71 | 0.91 | — | ||||||||||||

| (2) PNI-VN | 3.05 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.67 | — | |||||||||||

| (3) OOP | 3.15 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.31 | 0.22 | — | ||||||||||

| (4) SPP | 2.79 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.31 | 0.55 | 0.22 | — | |||||||||

| (5) SOP | 3.75 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.24 | — | ||||||||

| (6) FDSE | 2.49 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.18 | — | |||||||

| (7) FIOLI | 2.03 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.52 | — | ||||||

| (8) FUIO | 2.22 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.36 | 0.57 | 0.16 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.76 | — | |||||

| (9) FSE | 2.78 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.64 | — | ||||

| (10) Appr. Success | 695 | 126 | . | −0.19 | −0.12 | −0.00 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.00 | −0.17 | — | |||

| (11) Avd. Failure | 744 | 139 | . | −0.17 | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.18 | 0.88 | — | ||

| (12) Appr. Failure | 799 | 162 | . | −0.19 | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.72 | 0.75 | — | |

| (13) Avd. Success | 799 | 151 | . | −0.19 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.00 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.88 | — |

| Outcome Variable (Perfectionism Subtype) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | OOP a | p | b | SPP b | p | b | SOP c | p | |||

| SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | |||||||

| (1) Grandiose | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.30 | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.006 |

| (2) Vulnerable | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.62 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneider, S.; Kornberger, S.; Aßmuth, A.A.; Mokros, A. Am I (Not) Perfect? Fear of Failure Mediates the Link Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perfectionism. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091214

Schneider S, Kornberger S, Aßmuth AA, Mokros A. Am I (Not) Perfect? Fear of Failure Mediates the Link Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perfectionism. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091214

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneider, Sabrina, Sabrina Kornberger, Angela Aja Aßmuth, and Andreas Mokros. 2025. "Am I (Not) Perfect? Fear of Failure Mediates the Link Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perfectionism" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091214

APA StyleSchneider, S., Kornberger, S., Aßmuth, A. A., & Mokros, A. (2025). Am I (Not) Perfect? Fear of Failure Mediates the Link Between Vulnerable Narcissism and Perfectionism. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091214