Do Family Obligations Contribute to Academic Values? The Mediating Role of Academic Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Family Obligations

1.2. Academic Efficacy as a Mediator

1.3. Study Rationale

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

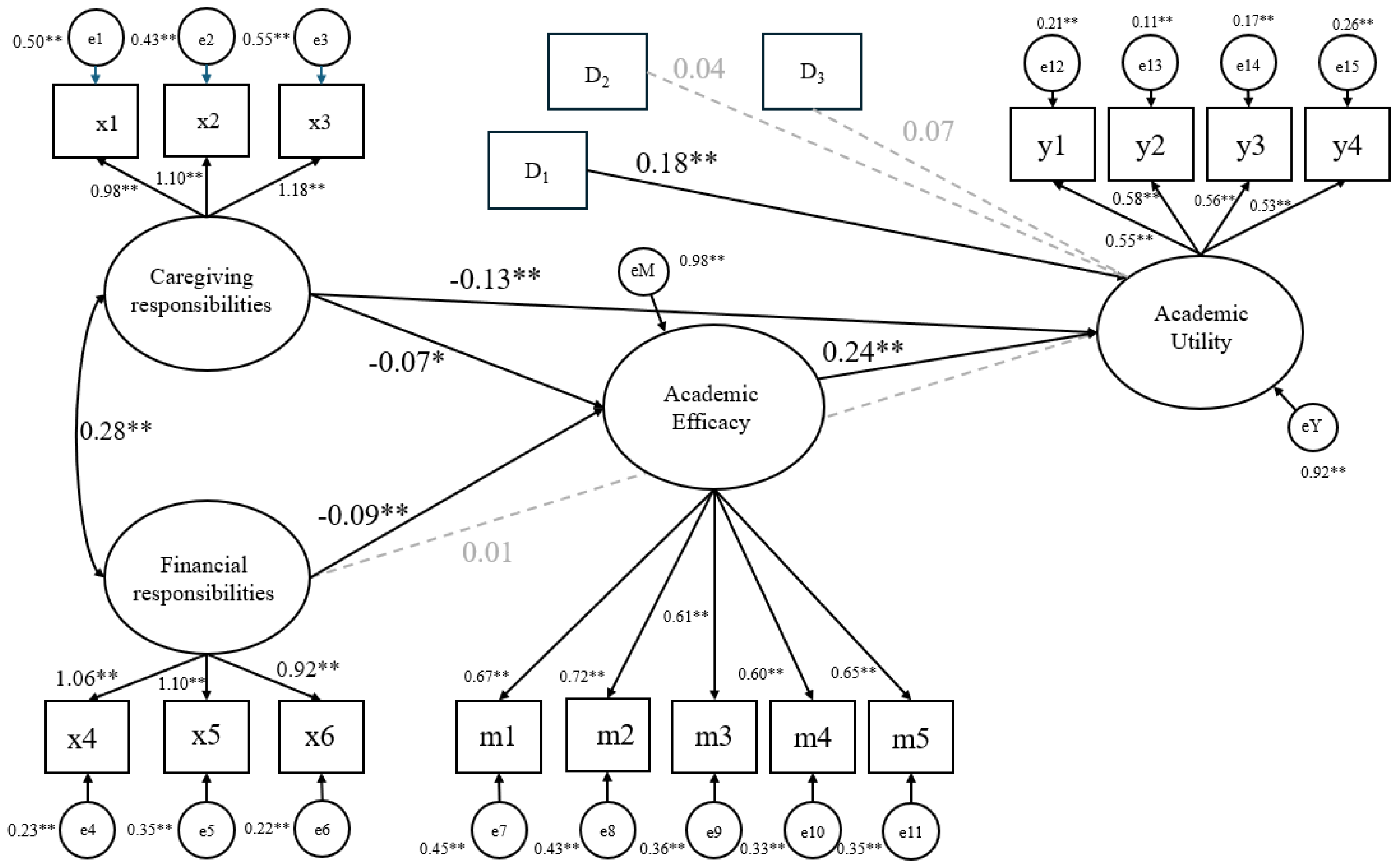

2.2.1. Model

2.2.2. Variable List

- Dependent Variable

- 2.

- Predictors

- 3.

- Mediator

- 4.

- Covariates

2.2.3. Equations

- Measurement Model

- 2.

- Structural Equation Model

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.2. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Model Fit and Parameter Estimates

3.3. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Developmental Context

4.2. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arana, R., Castañeda-Sound, C., Blanchard, S., & Aguilar, T. E. (2011). Indicators of persistence for Hispanic undergraduate achievement: Toward an ecological model. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 10(3), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Carter, E., Panter, A. T., Hutson, B., & Olson, E. A. (2022). A university-wide survey of caregiving students in the US: Individual differences and associations with emotional and academic adjustment. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bembenutty, H. (2008). The last word: The scholar whose expectancy-value theory transformed the understanding of adolescence, gender differences, and achievement: An interview with Jacquelynne S Eccles. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19(3), 531–532. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, C. Z., Dinwiddie, G., & Massey, D. S. (2004). The continuing consequences of segregation: Family stress and college academic performance: Social science examines education. Social Science Quarterly, 85(5), 1353–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. W., & Wong, Y. L. (2014). What my parents make me believe in learning: The role of filial piety in Hong Kong students’ motivation and academic achievement. International Journal of Psychology, 49(4), 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrier, B., Lamore, K., Untas, A., & Dorard, G. (2022). Young adult carers’ identification, characteristics, and support: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 990257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H., Marin, M. R., Schwartz, J. P., Pham, A., & Castro-Olivo, S. M. (2016). Psychosociocultural structural model of college success among Latina/o students in Hispanic-serving institutions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 9(4), 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, A. M. (2012). Patterns of motivation beliefs: Combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(3), 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A. J. (2001). Family obligation and the academic motivation of adolescents from asian, latin american, and european backgrounds. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2001(94), 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A. J., & Pedersen, S. (2002). Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A. J., Tseng, V., & Lam, M. (1999). Attitudes toward family obligations among american adolescents with asian, latin american, and european backgrounds. Child Development, 70(4), 1030–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A. J., & Witkow, M. (2004). The Postsecondary educational progress of youth from immigrant families. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14(2), 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A., Piña-Watson, B., & Manzo, G. (2022). Resilience through family: Family support as an academic and psychological protective resource for Mexican descent first-generation college students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 21(3), 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. M. (2019). The uncertain future of American public higher education: Student-centered strategies for sustainability. Palgrave Mcmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I., Kim, J., Ma, Y., & Seo, C. (2015). Mediating effect of academic self-efficacy on the relationship between academic stress and academic burnout in Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Human Ecology, 16(2), 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Soler, M. C., Zhao, Z., & Swirsky, E. (2024). Race and ethnicity in higher education: Status report. American Council of Education. [Google Scholar]

- King, M. K., Xue, B., Lacey, R., Di Gessa, G., Wahrendorf, M., McMunn, A., & Deindl, C. (2023). Does young adulthood caring influence educational attainment and employment in the UK and Germany? Journal of Social Policy, 54, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C. A., & Fong, C. J. (2024). Undergraduate Latina/o/x motivation and STEM persistence intentions: Moderating influences of community cultural wealth. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 12(2), 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBouef, S., & Dworkin, J. (2021). First-generation college students and family support: A critical review of empirical research literature. Education Sciences, 11(6), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Han, M., Cohen, G. L., & Markus, H. R. (2021). Passion matters but not equally everywhere: Predicting achievement from interest, enjoyment, and efficacy in 59 societies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(11), e2016964118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorca, A., Cristina Richaud, M., & Malonda, E. (2017). Parenting, peer relationships, academic self-efficacy, and academic achievement: Direct and mediating effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S. R., & Naumann, L. P. (2024). “Is it worth it?”: Academic-related guilt among college student caregivers. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 18, S626–S635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2024). Past due! Racializing aspects of situated expectancy-value theory through the lens of critical race theory. Motivation Science, 10(3), 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L. Z., Anderman, E. M., Anderman, L. H., Freeman, K. E., & Urdan, T. (2000). Manual for the patterns of adaptive learning scales (PALS). University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, K. J. (2014). Development and initial validation of a measure of work, family, and school conflict. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuji, U. S., Mooring, S. R., & Glover, C. S. (in press). Characterizing the ecological factors influencing first-year STEM College students’ engagement. Journal of the First-Year Experience & Students in Transition.

- Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66, 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P., Smith, D., García, T., & McKeachie, W. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A., Rivera, D. B., Valadez, A. M., Mattis, S., & Cerezo, A. (2023). Examining mental health, academic, and economic stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic among community college and 4-year university students. Community College Review, 51(3), 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichlin, L., Eckerson, E., & Gault, B. (2018). Brief Report, IWPR #C412. Understanding the new college majority: The demographic and financial characteristics of independent students and their postsecondary outcomes. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, K. A., & Shankar, S. (2025). Motivational trajectories and experiences of minoritized students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: A critical quantitative examination of existing data. Journal of Educational Psychology, 117(3), 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskowski, C. (2006). Young caregivers: Effect of family health situations on school performance. The Journal of School Nursing, 22(3), 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, S. R., & Romero, J. (2008). Family responsibilities among Latina college students from immigrant families. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 7(3), 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telzer, E. H., Masten, C. L., Berkman, E. T., Lieberman, M. D., & Fuligni, A. J. (2010). Gaining while giving: An fmri study of the rewards of family assistance among white and Latino youth. Social Neuroscience, 5(5–6), 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyokawa, N., & Toyokawa, T. (2019). Interaction effect of familism and socioeconomic status on academic outcomes of adolescent children of Latino immigrant families. Journal of Adolescence, 71(1), 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiser, D. A., & Riggio, H. R. (2010). Family background and academic achievement: Does self-efficacy mediate outcomes? Social Psychology of Education, 13(3), 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A. V., & Perrone-McGovern, K. (2017). Influence of generational status and financial stress on academic and career self-efficacy. Journal of Employment Counseling, 54(1), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2023). What is next for situated expectancy-value theory? A reply to our commentators. Motivation Science, 9(1), 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, Y. (2025). The balancing act of family and college: Reciprocity and its consequences for black students. Social Problems, 72(1), 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B., Lacey, R. E., Di Gessa, G., & McMunn, A. (2023). Does providing informal care in young adulthood impact educational attainment and employment in the UK? Advances in Life Course Research, 56, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -- | 0.25 ** | −0.10 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.08 ** | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| 2 | -- | -- | −0.10 ** | −0.06 * | −0.05 | 0.17 * | −0.07 ** |

| 3 | -- | -- | -- | 0.20 ** | −0.07 * | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| 4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.07 ** | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| 5 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.06 * | 0.15 ** |

| 6 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.46 ** |

| Mean | 6.80 | 5.01 | 21.10 | 17.66 | -- | -- | |

| SD | 3.48 | 3.18 | 3.57 | 2.48 | |||

| Range | 3–15 | 3–15 | 5–25 | 4–20 | -- | -- | -- |

| Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Direct effects on Academic Utility (Y) | |||||

| Caregiving Responsibilities | −0.130 | 0.032 | −0.195 | 0.071 | 0.00 |

| Financial Responsibilities | 0.007 | 0.031 | −0.054 | 0.067 | 0.82 |

| Academic Efficacy (M) | 0.238 | 0.037 | 0.167 | 0.314 | 0.000 |

| Gender (D1) 1 | 0.176 | 0.063 | 0.054 | 0.299 | 0.005 |

| African American/Black (D2) 2 | 0.039 | 0.075 | −0.108 | 0.188 | 0.598 |

| Latinx (D3) 3 | 0.071 | 0.063 | −0.052 | 0.196 | 0.260 |

| First paths of mediation | |||||

| Effect of X1 on M (a2) | −0.073 | 0.031 | −0.135 | −0.013 | 0.018 |

| Effects of X2 on M (b2) | −0.094 | 0.034 | −0.161 | −0.030 | 0.005 |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| X1 × M 4 | −0.017 | 0.008 | −0.034 | −0.003 | 0.028 |

| X2 × M 5 | −0.022 | 0.009 | −0.041 | −0.007 | 0.010 |

| Total indirect effects | −0.040 | 0.011 | −0.063 | −0.021 | 0.000 |

| Total effect | 0.361 | 0.134 | 0.102 | 0.626 | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Glover, C.S.; Bámaca, M.Y.; Homma, K. Do Family Obligations Contribute to Academic Values? The Mediating Role of Academic Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091212

Glover CS, Bámaca MY, Homma K. Do Family Obligations Contribute to Academic Values? The Mediating Role of Academic Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091212

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlover, Ciara S., Mayra Y. Bámaca, and Kazumi Homma. 2025. "Do Family Obligations Contribute to Academic Values? The Mediating Role of Academic Efficacy" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091212

APA StyleGlover, C. S., Bámaca, M. Y., & Homma, K. (2025). Do Family Obligations Contribute to Academic Values? The Mediating Role of Academic Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1212. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091212