Examination of the Top Three Traumatic Experiences Among United States Service Members and Veterans with Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analytic Strategy

3. Results

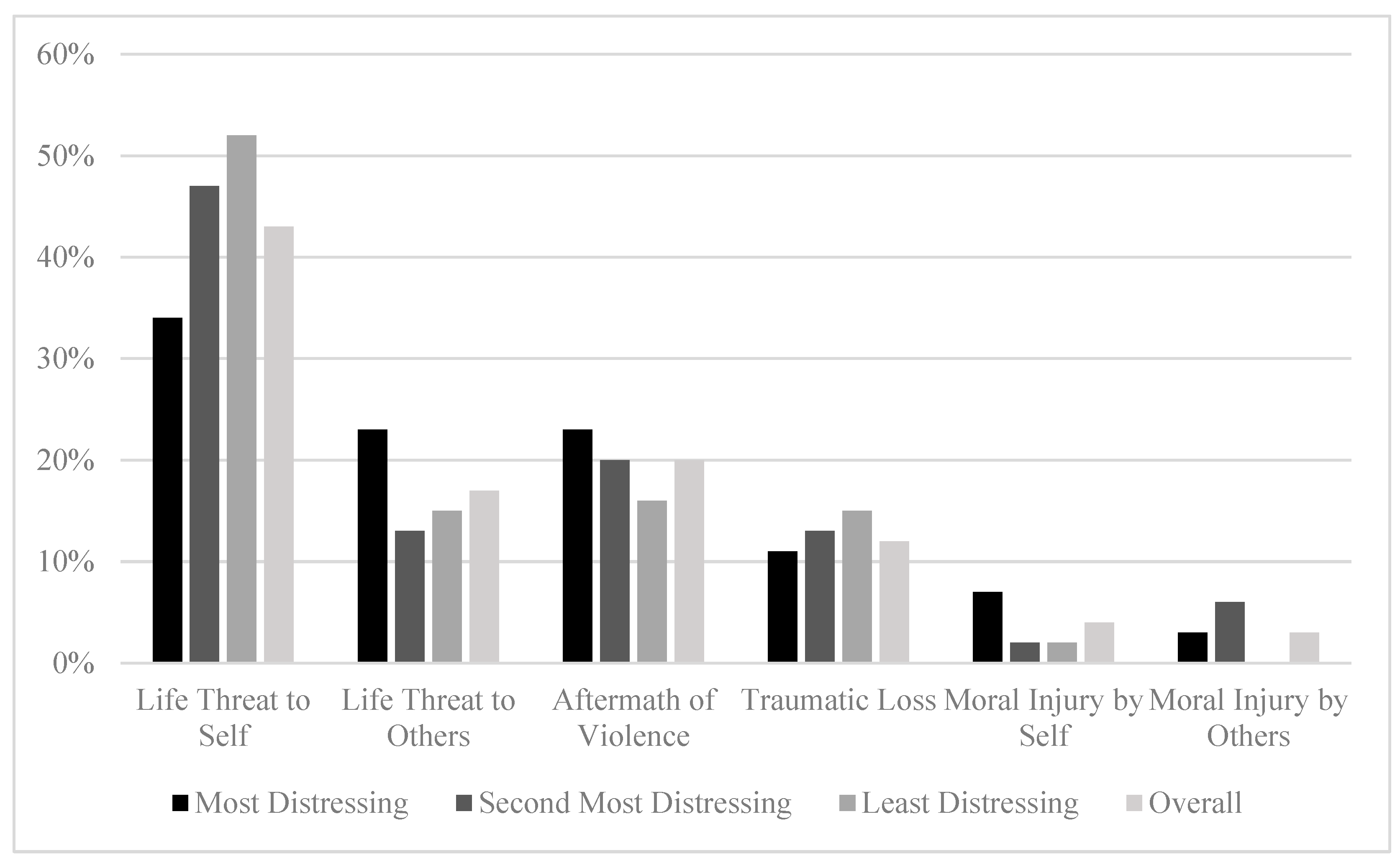

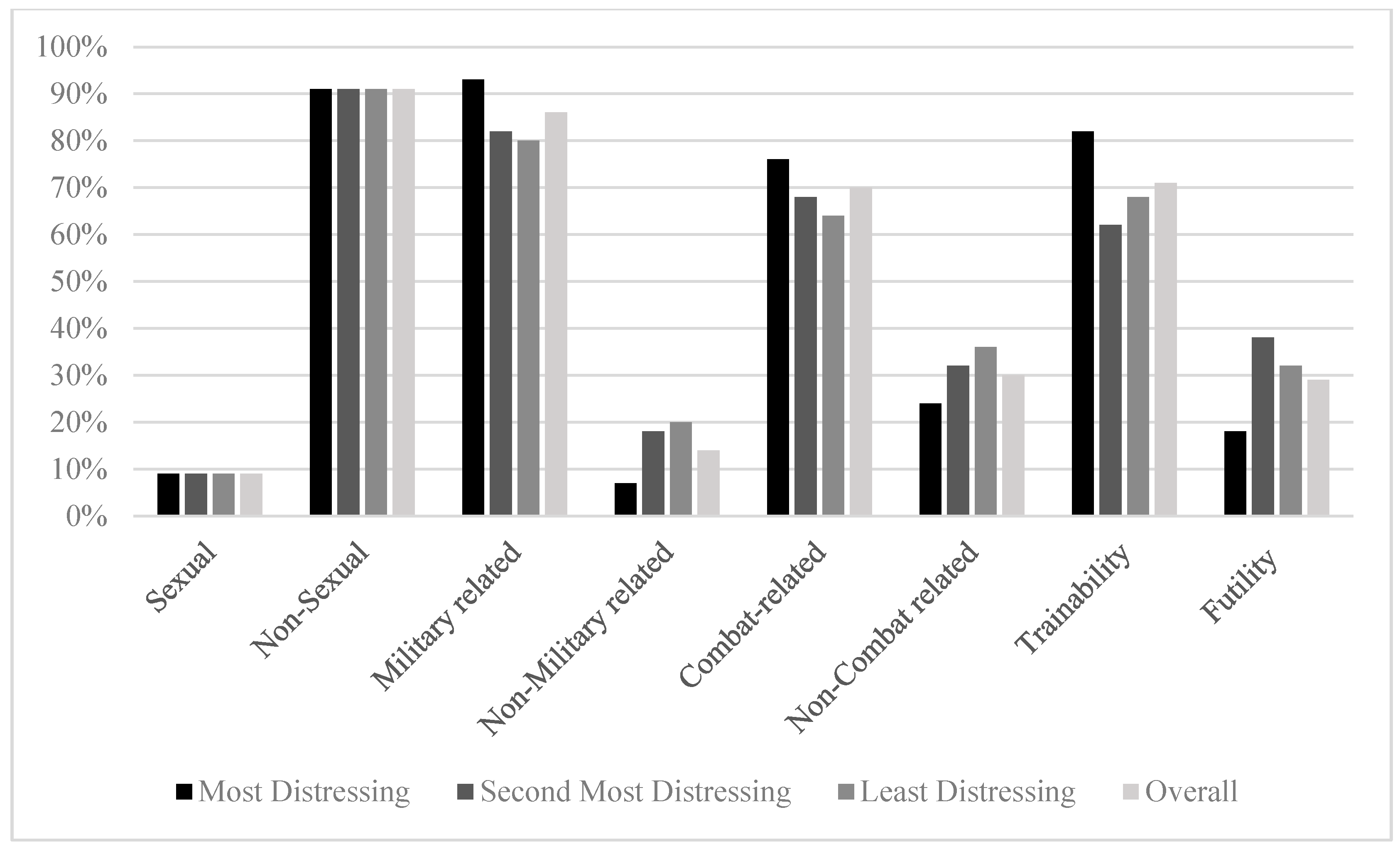

3.1. Prevalence of Trauma Types

3.1.1. All Traumatic Experiences

- Traumatic Experiences

3.1.2. Most Distressing Trauma

3.1.3. Second Most Distressing Trauma

3.1.4. Third Most Distressing Trauma

3.2. Demographic and Military Characteristics and Trauma Types

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Abbreviations

| CAPS-5 | Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders |

| IED | Improvised Explosive Device |

| IOP | Intensive Outpatient Program |

| PE | Prolonged Exposure |

| PTSD | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

Appendix A

| Category | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| Litz classification (Stein et al., 2012) | |

| Life Threat to Self | Personal exposure to the threat of death or actual or threatened serious injury |

| Life Threat to Others | Personal exposure to the actual or threatened death of others |

| Aftermath of Violence | Personal exposure to grotesque or haunting images, sounds, or smells of dead or severely injured humans or animals |

| Traumatic Loss | Witnessed or learned about the death of a family member, friend, or unit member |

| Moral Injury by Self | Committing an act that is perceived to be a gross violation of moral or ethical standards (e.g., killing or injuring others, rape, atrocities). A service member who nearly committed these acts could also experience moral injury. |

| Moral Injury by Others | Witnessing or being victim of an act that is perceived to be a gross violation of moral or ethical standards (e.g., killing or injuring civilians, rape, atrocities, betrayal). Events can also be indirectly experienced (i.e., learned about) if they are directly relevant to the individual. |

| Not within Litz classification | Experiences that do not fit within the definitions of the six categories defined above. |

| Sexual trauma classification | |

| Sexual trauma | Traumatic experiences related to sexual trauma/assault in a deployed or non-deployed setting. Can include childhood sexual trauma, military sexual trauma, etc. |

| Non-sexual trauma | Factors not related to sexual trauma/assault. |

| Military trauma classification | |

| Military-related | Factors related to military service, whether combat related or not. Examples include traumatic experiences that occur during training, military sexual trauma, combat related trauma, negative interactions with civilians in a deployed setting, etc. |

| Non-military-related | Factors not related to military service, combat, military training, etc. This includes events that occur in a civilian setting, such as childhood sexual assault, motor vehicle accidents, non-military related death of a loved one, etc. |

| Combat trauma classification | |

| Combat-related | Factors directly (confronting enemy combatants) or indirectly (providing care to a service member injured in combat, mortuary services, etc.) related to combat |

| Noncombat-related | Factors not related to combat, such as military sexual assault, motor vehicle accidents in a civilian/non-deployed setting, etc. |

| Trainability classification (Hale et al., 2021) | |

| Trainability | Factors that could be anticipated and prepared for via training, that the service member reasonably feels they could have mitigated. This can include medically treating fellow service members for common wounds. |

| Futility | Events that are reasonably perceived as outside of the service member’s control. This can include events such as trying to medically treat a service member who was too badly injured to be stabilized, events that the service member heard about but was not physically present for (e.g., death of a loved one), etc. |

Appendix B

| Life Treat to Self (n = 119) | Life Threat to Others (n = 47) | Aftermath of Violence (n =55) | Traumatic Loss (n = 34) | Moral Injury by Self (n = 11) | Moral Injury by Others (n = 8) | Sexual Trauma (n = 27) | Military-Related (n = 248) | Combat-Related (n = 202) | Trainability (n = 210) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||||||||

| Age (F) | 0.96 | 4.71 * | 0.07 | 0.87 | 2.1 | |||||

| Gender (χ2) | 22.9 *** | 68.52 *** | 7.46 ** | 28.24 *** | 21.82 *** | |||||

| Women | 31.9 (38) a | 17 (8) | 5.5 (3) b | 5.9 (2) b | 18.2 (2) | 12.5 (1) | 77.8 (21) a | 15.7 (39) b | 10.9 (22) b | 11.9 (25) b |

| Men | 68.1 (81) b | 83 (39) | 94.5 (52) a | 94.1 (32) a | 81.8 (9) | 87.5 (7) | 22.2 (6) b | 84.3 (209) a | 89.1 (180) a | 88.1 (185) a |

| Marital Status (χ2) | 6.66 | 4.95 * | 1.89 | 0.73 | 1.25 | |||||

| Married | 73.1 (87) | 85.1 (40) | 76.4 (42) | 67.6 (23) | 54.5 (6) | 62.5 (5) | 55.6 (15) b | 73.4 (182) | 75.2 (152) | 75.7 (159) |

| Not Married | 26.9 (32) | 14.9 (7) | 23.6 (13) | 32.4 (11) | 45.5 (5) | 37.5 (3) | 44.4 (12) a | 26.6 (66) | 24.8 (50) | 24.3 (51) |

| Race and ethnicity (χ2) | 13.38 | 4.49 | 0.39 | 1.56 | 3.94 | |||||

| African American | 32.2 (37) | 37.8 (17) | 28.3 (15) | 18.8 (6) | 9.1 (1) | 37.5 (3) | 44.4 (12) | 29.5 (71) | 27.8 (55) | 26.8 (55) |

| Hispanic | 37.4 (43) | 42.2 (19) | 41.5 (22) | 43.8 (14) | 63.6 (7) | 50 (4) | 25.9 (7) | 40.7 (98) | 41.9 (83) | 43.4 (89) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 26.1 (30) | 17.8 (8) | 30.2 (16) | 34.4 (11) | 18.2 (2) | 12.5 (1) | 29.6 (8) | 27 (65) | 27.8 (55) | 26.8 (55) |

| Other | 4.3 (5) | 2.2(1) | 0 (0) | 3.1 (1) | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2.9 (7) | 2.5 (5) | 2.9 (6) |

| Education (χ2) | 3.41 | 0 | 0.73 | 3.77 | 2 | |||||

| ≤Some college | 39.5 (47) | 44.7 (21) | 52.7 (29) | 41.2 (14) | 54.5 (6) | 50 (4) | 44.4 (12) | 45.2 (112) | 47.5 (96) | 46.7 (98) |

| ≥Associate degree | 60.5 (72) | 55.3 (26) | 47.3 (26) | 58.8 (20) | 45.5 (5) | 50 (4) | 55.6 (15) | 54.8 (136) | 52.5 (106) | 53.3 (11) |

| Status (χ2) | 3.7 | 2.12 | 3.3 | 2.77 | 0.38 | |||||

| Active duty | 70.6 (84) | 63.8 (30) | 76.4 (42) | 73.5 (25) | 72.7 (8) | 50 (4) | 81.5 (22) | 66.9 (166) | 66.3 (134) | 68.1 (143) |

| Veteran | 29.4 (35) | 36.2 (17) | 23.6 (13) | 26.5 (9) | 27.3 (3) | 50 (4) | 18.5 (5) | 33.1 (82) | 33.7 (67) | 31.9 (67) |

| Branch (χ2) | 7.56 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 3.36 | 0.04 | |||||

| Army | 75.6 (90) | 78.7 (37) | 87.3 (48) | 91.2 (31) | 81.8 (9) | 62.5 (5) | 77.8 (21) | 79.8 (198) | 83.2 (168) | 81 (170) |

| Other | 24.4 (29) | 21.3 (10) | 12.7 (7) | 8.8 (3) | 18.2 (2) | 37.5 (3) | 22.2 (6) | 20.2 (50) | 16.8 (34) | 19 (40) |

| Time in Military (F) | 1.39 | 2.43 | 0.17 | 0.62 | 4.73 * | |||||

| Occupational Specialty (χ2) | 6.7 | 20.48 *** | 8.68 * | 10.15 ** | 9.22 ** | |||||

| Combat arms | 36.2 (42) | 36.2 (17) | 41.8 (23) | 55.9 (19) a | 36.4 (4) | 50 (4) | 4 (1) b | 44.9 (110) a | 47.3 (95) a | 46.9 (98) a |

| Combat support | 26.7 (31) | 34 (16) | 25.5 (14) | 20.6 (7) | 36.4 (4) | 25 (2) | 28 (7) | 24.9 (61) b | 26.4 (53) | 24.9 (52) |

| Combat service support | 37.1 (43) | 29.8 (14) | 32.7 (18) | 23.5 (8) | 27.3 (3) | 25 (2) | 68 (17) a | 30.2 (74) | 26.4 (53) b | 28.2 (59) b |

| Rank (χ2) | 3.3 | 0.06 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.67 | |||||

| Enlisted | 86.6 (103) | 89.4 (42) | 87.3 (48) | 79.4 (27) | 90.9 (10) | 100 (8) | 88.9 (24) | 87.1 (216) | 86.6 (175) | 87.1 (183) |

| Officer | 13.4 (16) | 10.6 (5) | 12.7 (7) | 20.6 (7) | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 11.1 (3) | 12.9 (32) | 13.4 (27) | 12.9 (27) |

| Deployments, No. (χ2) | 23.2 | 9.73 * | 6.39 | 8.24 * | 13.13 ** | |||||

| 1 | 22.4 (26) | 27.7 (13) | 16.4 (9) | 26.5 (9) | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 24 (6) | 20.4 (50) b | 19.4 (39) b | 18.2 (38) b |

| 2 | 35.3 (41) | 31.9 (15) | 27.3 (15) | 20.6 (7) | 45.5 (5) | 50 (4) | 56 (14) a | 32.2 (79) | 29.4 (59) | 31.1 (65) |

| 3 | 23.3 (27) | 19.1 (9) | 27.3 (15) | 11.8 (4) | 45.5 (5) | 37.5 (3) | 12 (3) | 23.3 (57) | 25.9 (52) a | 26.3 (55) a |

| ≥4 | 19 (22) | 21.3 (10) | 29.1 (16) | 41.2 (14) a | 0 (0) | 12.5 (1) | 8 (2) | 24.1 (59) | 25.4 (51) | 24.4 (51) |

| Life Treat to Self (n = 35) | Life Threat to Others (n = 24) | Aftermath of Violence (n =24) | Traumatic Loss (n = 11) | Moral Injury by Self (n = 7) | Moral Injury by Others (n = 3) | Sexual Trauma (n = 10) | Military-Related (n = 101) | Combat-Related (n = 83) | Trainability (n = 90) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||||||||

| Age (F) | 0.74 | 4.62 * | 0.01 | 2.68 | 4.36 * | |||||

| Gender (χ2) | 5.87 | 24.75 *** | 17.24 *** | 24.02 *** | 24.44 *** | |||||

| Women | 28.6 (10) | 29.2 (7) | 8.3 (2) | 9.1 (1) | 14.3 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 80 (8) a | 14.9 (15) b | 9.6 (8) b | 11.1 (10) b |

| Men | 71.4 (25) | 70.8 (17) | 91.7 (22) | 90.9 (10) | 85.7 (6) | 66.7 (2) | 20 (2) b | 85.1 (86) a | 90.4 (75) a | 88.9 (80) a |

| Marital Status (χ2) | 3.16 | 2.59 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.56 | |||||

| Married | 74.3 (26) | 83.3 (20) | 66.7 (16) | 63.6 (7) | 57.1 (4) | 66.7 (2) | 50 (5) | 72.3 (73) | 73.5 (61) | 73.3 (66) |

| Not Married | 25.7 (9) | 16.7 (4) | 33.3 (8) | 36.4 (4) | 42.9 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 50 (5) | 27.7 (28) | 26.5 (22) | 26.7 (24) |

| Race and ethnicity (χ2) | 12.97 | 3.26 | 0.32 | 0.9 | 2.54 | |||||

| African American | 32.4 (11) | 39.1 (9) | 30.4 (7) | 0 (0)b | 14.3 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 50 (5) | 29.6 (29) | 29.6 (24) | 27.3 (24) |

| Hispanic | 29.4 (10) | 21.7 (5) | 30.4 (7) | 40 (4) | 14.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 10 (1) | 27.6 (27) | 29.6 (24) | 29.5 (26) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 32.4 (11) | 34.8 (8) | 39.1 (9) | 60 (6) | 57.1 (4) | 66.7 (2) | 40 (4) | 38.8 (38) | 37 (30) | 38.6 (34) |

| Other | 5.9 (2) | 4.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4.1 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 4.5 (4) |

| Education (χ2) | 2.94 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 3.65 | 1.85 | |||||

| ≤Some college | 42.9 (15) | 50 (12) | 45.8 (11) | 27.3 (3) | 28.6 (2) | 66.7 (2) | 40 (4) | 43.6 (44) | 48.2 (40) | 46.7 (42) |

| ≥Associates degree | 57.1 (20) | 50 (12) | 54.2 (13) | 72.7 (8) | 71.4 (5) | 33.3 (1) | 60 (6) | 56.4 (57) | 51.8 (43) | 53.3 (48) |

| Status (χ2) | 1.76 | 0.71 | 0.2 | 3.98 * | 0.52 | |||||

| Active duty | 71.4 (23) | 58.3 (14) | 70.8 (17) | 72.7 (8) | 57.1 (4) | 66.7 (2) | 80 (8) | 67.3 (68) | 63.9 (53) b | 66.7 (60) |

| Veteran | 28.6 (10) | 41.7 (10) | 29.2 (7) | 27.3 (3) | 42.9 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 20 (2) | 32.7 (33) | 36.1 (30) a | 33.3 (30) |

| Branch (χ2) | 2.7 | 0 | 0.12 | 4.41 * | 1.53 | |||||

| Army | 77.1 (27) | 70.8 (17) | 83.3 (20) | 90.9 (10) | 85.7 (6) | 66.7 (2) | 80 (8) | 80.2 (81) | 84.3 (70) a | 82.2 (74) |

| Other | 22.9 (8) | 29.2 (7) | 16.7 (4) | 9.1 (1) | 14.3 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 20 (2) | 19.8 (20) | 15.7 (13) b | 17.8 (16) |

| Time in Military (F) | 0.42 | 2.12 | 0.07 | 1.44 | 3.99 * | |||||

| Occupational Specialty (χ2) | 4.95 | 6.71 * | 10.06 ** | 5.83 | 8.85 * | |||||

| Combat arms | 35.3 (12) | 33.3 (8) | 37.5 (9) | 54.5 (6) | 42.9 (3) | 66.7 (2) | 0 (0) b | 44 (44) a | 47 (39) a | 46.7 (42) a |

| Combat support | 26.5 (9) | 33.3 (8) | 29.2 (7) | 18.2 (2) | 42.9 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 44.4 (4) | 25 (25) b | 25.3 (21) | 24.4 (22) b |

| Combat service support | 38.2 (13) | 33.3 (8) | 33.3 (8) | 27.3 (3) | 14.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 55.6 (5) | 31 (31) | 27.7 (23) | 28.9 (26) |

| Rank (χ2) | 4.65 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.27 | |||||

| Enlisted | 91.4 (32) | 91.7 (22) | 79.2 (19) | 72.7 (8) | 85.7 (6) | 100 (3) | 90 (9) | 86.1 (87) | 86.7 (72) | 85.6 (77) |

| Officer | 8.6 (3) | 8.3 (2) | 20.8 (5) | 27.3 (3) | 14.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 10 (1) | 13.9 (14) | 13.3 (11) | 14.4 (13) |

| Deployments, No. (χ2) | 14.62 | 3.29 | 1.42 | 6.69 | 5.35 | |||||

| 1 | 23.5 (8) | 29.2 (7) | 29.2 (7) | 18.2 (2) | 14.3 (1) | 0 (0) | 33.3 (3) | 24 (24) | 21.7 (18) | 22.2 (20) |

| 2 | 29.4 (10) | 29.2 (7) | 29.2 (7) | 36.4 (4) | 57.1 (4) | 33.3 (1) | 44.4 (4) | 30 (30) | 26.5 (22) | 27.8 (25) |

| 3 | 20.6 (7) | 25 (6) | 16.7 (4) | 0 (0) | 28.6 (2) | 66.7 (2) a | 22.2 (2) | 21 (21) | 22.9 (19) | 23.3 (21) |

| ≥4 | 26.5 (9) | 16.7 (4) | 25 (6) | 45.5 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (25) | 28.9 (24) a | 26.7 (24) |

| Life Treat to Self (n = 41) | Life Threat to Others (n = 11) | Aftermath of Violence (n = 18) | Traumatic Loss (n = 11) | Moral Injury by Self (n = 2) | Moral Injury by Others (n = 5) | Sexual Trauma (n = 9) | Military-Related (n = 79) | Combat-Related (n = 65) | Trainability (n = 60) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||||||||

| Age (F) | 0.67 | 1.5 | 1.62 | 0 | 0.01 | |||||

| Gender (χ2) | 15.31 ** | 16.57 *** | 4.38 * | 6.65 * | 3.74 | |||||

| Women | 36.6 (15) a | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) b | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 66.7 (6) a | 13.9 (11) b | 89.2 (58) a | 11.7 (7) |

| Men | 63.4 (26) b | 90.9 (10) | 100 (18) a | 90.9 (10) | 100 (2) | 100 (5) | 33.3 (3) b | 86.1 (68) a | 10.8 (7) b | 88.3 (53) |

| Marital Status (χ2) | 6.03 | 1.81 | 0.21 | 3.82 | 4.55 * | |||||

| Married | 70.7 (29) | 90.9 (10) | 83.3 (15) | 54.5 (6) | 100 (2) | 60 (3) | 55.6 (5) | 75.9 (60) | 80 (52) a | 81.7 (49) a |

| Not Married | 29.3 (12) | 9.1 (1) | 16.7 (3) | 45.5 (5) | 0 (0) | 40 (2) | 44.4 (4) | 24.1 (19) | 20 (13) b | 18.3 (11) b |

| Race and ethnicity (χ2) | 8.69 | 0.44 | 2.28 | 1.7 | 2.79 | |||||

| African American | 35.9 (14) | 40 (4) | 16.7 (3) | 36.4 (4) | 0 (0) | 40 (2) | 33.3 (3) | 28.6 (22) | 26.6 (17) | 27.1 (16) |

| Hispanic | 23.1 (9) | 10 (1) | 33.3 (6) | 27.3 (3) | 50 (1) | 20 (1) | 33.3 (3) | 28.6 (22) | 29.7 (19) | 25.4 (15) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 38.5 (15) | 50 (5) | 50 (9) | 27.3 (3) | 50 (1) | 40 (2) | 33.3 (3) | 41.6 (32) | 42.2 (27) | 45.8 (27) |

| Other | 2.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (1) | 1.6 (1) | 1.7 (1) |

| Education (χ2) | 5.5 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 1.02 | |||||

| ≤ Some college | 36.6 (15) | 45.5 (5) | 61.1 (11) | 45.5 (5) | 100 (2) | 40 (2) | 55.6 (5) | 46.8 (37) | 46.2 (30) | 48.3 (29) |

| ≥ Associates degree | 63.4 (26) | 54.5 (6) | 38.9 (7) | 54.5 (6) | 0 (0) | 60 (3) | 44.4 (4) | 53.2 (42) | 53.8 (35) | 51.7 (31) |

| Status (χ2) | 5.55 | 0.43 | 2.03 | 0.88 | 0.01 | |||||

| Active duty | 70.7 (29) | 81.8 (9) | 77.8 (14) | 54.5 (6) | 100 (2) | 40 (2) | 77.8 (7) | 64.6 (51) | 64.6 (42) | 68.3 (41) |

| Veteran | 29.3 (12) | 18.2 (2) | 22.2 (4) | 45.5 (5) | 0 (0) | 60 (3) | 22.2 (2) | 35.4 (28) | 35.4 (23) | 31.7 (19) |

| Branch (χ2) | 8.4 | 0.09 | 2.25 | 0.1 | 0.22 | |||||

| Army | 75.6 (31) | 81.8 (9) | 94.4 (17) | 100 (11) | 50 (1) | 60 (3) | 77.8 (7) | 78.5 (62) | 81.5 (53) | 80 (48) |

| Other | 24.4 (10) | 18.2 (2) | 5.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 50 (1) | 40 (2) | 22.2 (2) | 21.5 (17) | 18.5 (12) | 20 (12) |

| Time in Military (F) | 0.41 | 1.6 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.26 | |||||

| Occupational Specialty (χ2) | 12.08 | 8.1 * | 2.95 | 4.1 | 1.35 | |||||

| Combat arms | 25 (10) b | 45.5 (5) | 55.6 (10) | 63.6 (7) | 50 (1) | 40 (2) | 0 (0) b | 44.9 (35) | 46.2 (30) | 45 (27) |

| Combat support | 30 (12) | 36.4 (4) | 27.8 (5) | 9.1 (1) | 50 (1) | 20 (1) | 25 (2) | 25.6 (20) | 27.7 (18) | 25 (15) |

| Combat service support | 45 (18) a | 18.2 (2) | 16.7 (3) | 27.3 (3) | 0 (0) | 40 (2) | 75 (6) a | 29.5 (23) | 26.2 (17) b | 30 (18) |

| Rank (χ2) | 3.17 | 1.4 | 0.83 | 3.6 | 1.0 | |||||

| Enlisted | 85.4 (35) | 90.9 (10) | 88.9 (16) | 72.7 (8) | 100 (2) | 100 (5) | 100 (9) | 86.1 (68) | 83.1 (54) | 85 (51) |

| Officer | 14.6 (6) | 9.1 (1) | 11.1 (2) | 27.3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13.9 (11) | 16.9 (11) | 15 (9) |

| Deployments, No. (χ2) | 15.87 | 5.43 | 0.53 | 1.14 | 1.47 | |||||

| 1 | 25 (10) | 18.2 (2) | 11.1 (2) | 36.4 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (2) | 23.1 (18) | 24.6 (16) | 20 (12) |

| 2 | 35 (14) | 36.4 (4) | 27.8 (5) | 9.1 (1) | 0 (0) | 60 (3) | 62.5 (5) a | 30.8 (24) | 27.7 (18) | 31.7 (19) |

| 3 | 22.5 (9) | 27.3 (3) | 22.2 (4) | 27.3 (3) | 100 (2) a | 20 (1) | 12.5 (1) | 21.8 (17) | 23.1 (15) | 25 (15) |

| ≥4 | 17.5 (7) | 18.2 (2) | 38.9 (7) | 27.3 (3) | 0 (0) | 20 (1) | 0 (0) b | 24.4 (19) | 24.6 (16) | 23.3 (14) |

| Life Treat to Self (n = 43) | Life Threat to Others (n = 12) | Aftermath of Violence (n =13) | Traumatic Loss (n = 12) | Moral Injury by Self (n = 2) | Moral Injury by Others (n = 0) | Sexual Trauma (n = 8) | Military-Related (n = 68) | Combat-Related (n = 54) | Trainability (n = 60) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||||||||

| Age (F) | 0.11 | 0.05 | 2.85 | 0.02 | 0.46 | |||||

| Gender (χ2) | 11.8 * | - | 28.42 *** | 0.51 | 3.33 | 2.98 | ||||

| Women | 30.2 (13) a | 0 (0) | 7.7 (1) | 0 (0) | 50 (1) | - | 87.5 (7) a | 19.1 (13) | 13 (7) | 13.3 (8) |

| Men | 69.8 (30) b | 100 (12) | 92.3 (12) | 100 (12) | 50 (1) | - | 12.5 (1) b | 80.9 (55) | 87 (47) | 86.7 (52) |

| Marital Status (χ2) | 7.79 | - | 0.73 | 6.12 * | 1.49 | 0.82 | ||||

| Married | 74.4 (32) | 83.3 (10) | 84.6 (11) | 83.3 (10) | 0 (0) b | - | 62.5 (5) | 72.1 (49) b | 72.2 (39) | 73.3 (44) |

| Not Married | 25.6 (11) | 16.7 (2) | 15.4 (2) | 16.7 (2) | 100 (2) a | - | 37.5 (3) | 27.9 (19) a | 27.8 (15) | 26.7 (16) |

| Race and ethnicity (χ2) | 6.91 | - | 7.32 | 0.81 | 2.55 | 2.82 | ||||

| African American | 28.6 (12) | 33.3 (4) | 41.7 (5) | 18.2 (2) | 0 (0) | - | 50 (4) | 30.3 (20) | 26.4 (14) | 25.9 (15) |

| Hispanic | 26.2 (11) | 16.7 (2) | 25 (3) | 36.4 (4) | 0 (0) | - | 50 (4) | 24.2 (16) | 22.6 (12) | 24.1 (14) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 40.5 (17) | 50 (6) | 33.3 (4) | 45.5 (5) | 100 (2) | - | 0 (0) b | 42.4 (28) | 49.1 (26) | 48.3 (28) |

| Other | 4.8 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 1.9 (1) | 1.7 (1) |

| Education (χ2) | 4.14 | - | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.71 | 0.04 | ||||

| ≤ Some college | 39.5 (17) | 33.3 (4) | 53.8 (7) | 50 (6) | 100 (2) | - | 37.5 (3) | 45.6 (31) | 48.1 (26) | 45 (27) |

| ≥ Associates degree | 60.5 (26) | 66.7 (8) | 46.2 (8) | 50 (6) | 0 (0) | - | 62.5 (5) | 54.5 (37) | 51.9 (28) | 55 (33) |

| Status (χ2) | 5.39 | - | 1.1 | 1.18 | 0.02 | 0.24 | ||||

| Active duty | 69.8 (30) | 58.3 (7) | 84.6 (11) | 91.7 (11) | 100 (2) | - | 87.5 (7) | 69.1 (47) | 72.2 (39) | 70 (42) |

| Veteran | 30.2 (13) | 41.7 (5) | 15.4 (2) | 8.3 (1) | 0 (0) | - | 12.5 (1) | 30.9 (21) | 27.8 (15) | 30 (18) |

| Branch (χ2) | 2.65 | - | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.03 | 0.06 | ||||

| Army | 74.4 (32) | 91.7 (11) | 84.6 (11) | 83.3 (10) | 100 (2) | - | 75 (6) | 80.9 (55) | 83.3 (45) | 80 (48) |

| Other | 25.6 (11) | 8.3 (1) | 15.4 (2) | 16.7 (2) | 0 (0) | - | 25 (2) | 19.1 (13) | 16.7 (9) | 20 (12) |

| Time in Military (F) | 1.01 | 0.01 | 2.1 | 0.07 | 2.04 | |||||

| Occupational Specialty (χ2) | 9.23 | - | 8.02 * | 1.7 | 2.85 | 3.12 | ||||

| Combat arms | 47.6 (20) | 33.3 (4) | 30.8 (4) | 50 (6) | 0 (0) | - | 12.5 (1) | 46.3 (31) | 41.9 (26) | 49.2 (29) |

| Combat support | 23.8 (10) | 33.3 (4) | 15.4 (2) | 33.3 (4) | 0 (0) | - | 12.5 (1) | 23.9 (16) | 26.4 (14) | 25.4 (15) |

| Combat service support | 28.6 (12) | 33.3 (4) | 53.8 (7) | 16.7 (2) | 100 (2) a | - | 75 (6) a | 29.9 (20) | 24.5 (13) | 25.4 (15) |

| Rank (χ2) | 3.14 | - | 1.63 | 0.03 | 0.9 | 1.72 | ||||

| Enlisted | 83.7 (36) | 83.3 (10) | 100 (13) | 91.7 (11) | 100 (2) | - | 75 (6) | 89.7 (61) | 90.7 (49) | 91.7 (55) |

| Officer | 16.3 (7) | 16.7 (2) | 0 (0) | 8.3 (1) | 0 (0) | - | 25 (2) | 10.3 (7) | 9.3 (5) | 8.3 (5) |

| Deployments, No. (χ2) | 22.07 * | - | 4.94 | 11.85 ** | 14.02 ** | 15.48 *** | ||||

| 1 | 19 (8) | 33.3 (4) | 0 (0) | 25 (3) | 0 (0) | - | 12.5 (1) | 11.9 (8) b | 9.4 (5) b | 10.2 (6) b |

| 2 | 40.5 (17) | 33.3 (4) | 23.1 (3) | 16.7 (2) | 50 (1) | - | 62.5 (5) | 37.3 (25) | 35.8 (19) | 35.6 (21) |

| 3 | 26.2 (11) | 0 (0) b | 53.8 (7) a | 8.3 (1) | 50 (1) | - | 0 (0) | 28.4 (19) | 34 (18) a | 32.2 (19) a |

| ≥4 | 14.3 (6) | 33.3 (4) | 23.1 (3) | 50 (6) a | 0 (0) | - | 25 (2) | 22.4 (15) | 20.8 (11) | 22 (13) |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumba, J., & Bride, B. E. (2010). Trauma experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder among women in the United States military. Social Work in Mental Health, 8(3), 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardis, C. M., Reinhardt, K. M., Foynes, M. M., Medoff, N. E., & Street, A. E. (2018). “Who are you going to tell? who’s going to believe you?”: Women’s experiences disclosing military sexual trauma. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(4), 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedert, E. A., Green, K. T., Calhoun, P. S., Yoash-Gantz, R., Taber, K. H., Mumford, M. M., Tupler, L. A., Morey, R. A., Marx, C. E., Weiner, R. D., & Beckham, J. C. (2009). Association of trauma exposure with psychiatric morbidity in military veterans who have served since September 11, 2001. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(9), 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rond, M., & Lok, J. (2016). Some things can never be unseen: The role of context in psychological injury at war. The Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 1965–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B. J., Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Litz, B. T., Bryan, C. J., Schmitz, M., Villierme, C., Walsh, J., & Maguen, S. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guina, J., Nahhas, R. W., Sutton, P., & Farnsworth, S. (2018). The influence of trauma type and timing on PTSD symptoms. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 206(1), 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, W. J., Moore, B. A., Straud, C. L., Baker, M. T., & Peterson, A. L. (2021). Examination of the factor structure and correlates of the perceived military healthcare stressors scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(1), 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakob, J. M. D., Lamp, K., Rauch, S. A. M., Smith, E. R., & Buchholz, K. R. (2017). The impact of trauma type or number of traumatic events on PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity in treatment seeking veterans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(2), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellestad, L., Vital, N. A., Malamud, J., Taeymans, J., & Mueller-Pfeiffer, C. (2021). Functional impairment in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judkins, J. L., Moore, B. A., Collette, T. L., Hale, W. J., Peterson, A. L., & Morissette, S. B. (2020). Incidence rates of posttraumatic stress disorder over a 17-year period in active duty military service members. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(6), 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: DSM-5 PTSD prevalence. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., De Girolamo, G., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q. A., Doctor, J. N., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2018). Effects of treatment, choice, and preference on health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Quality of Life Research, 27(6), 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macia, K. S., Raines, A. M., Maieritsch, K. P., & Franklin, C. L. (2020). PTSD networks of veterans with combat versus non-combat types of index trauma. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L., Rosen, L. N., Durand, D. B., Knudson, K. H., & Stretch, R. H. (2000). Psychological and physical health effects of sexual assaults and nonsexual traumas among male and female united states army soldiers. Behavioral Medicine, 26(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, S. B., Haller, M., Kim, H. M., Allard, C. B., Porter, K. E., Stein, M. B., Venners, M. R., Authier, C. C., & Rauch, S. A. M. (2018). Trauma related guilt cognitions partially mediate the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and functioning among returning combat veterans. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 100, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A. L., Blount, T. H., Foa, E. B., Brown, L. A., McLean, C. P., Mintz, J., Schobitz, R. P., DeBeer, B. R., Mignogna, J., Fina, B. A., Evans, W. R., Synett, S., Hall-Clark, B. N., Rentz, T. O., Schrader, C., Yarvis, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Hansen, H., Jacoby, V. M., … Keane, T. M., for the Consortium to Alleviate PTSD. (2023). Massed vs. intensive outpatient prolonged exposure for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 6(1), e2249422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, A. L., Foa, E. B., Blount, T. H., McLean, C. P., Shah, D. V., Young-McCaughan, S., Litz, B. T., Schobitz, R. P., Castillo, D. T., Rentz, T. O., Yarvis, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Fina, B. A., Hall-Clark, B. N., Brown, L. A., DeBeer, B. R., Jacoby, V. M., Hancock, A. K., Williamson, D. E., … Keane, T. M., for the Consortium to Alleviate PTSD. (2018). Intensive prolonged exposure therapy for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Design and methodology of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 72, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, N. R., Mills, M. A., Arditte, K., Mendoza, C., Borah, A. M., Resick, P. A., Litz, B. T., STRONG STAR Consortium, Belinfante, K., Borah, E. V., Cooney, J. A., Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., Kippie, A., Lester, K., Malach, S. L., McClure, J., Peterson, A. L., Vargas, V., & Wright, E. (2012). A scheme for categorizing traumatic military events. Behavior Modification, 36(6), 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, C., Hofmann, M., Leichsenring, F., & Kruse, J. (2015). The course of PTSD in naturalistic long-term studies: High variability of outcomes. A systematic review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 69(7), 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S., Pan, W., & Wang, L. L. (2010). A comprehensive review of effect size reporting and interpreting practices in academic journals in education and psychology. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermetten, E., & Jetly, R. (2018). A critical outlook on combat-related PTSD: Review and case reports of guilt and shame as drivers for moral injury. Military Behavioral Health, 6(2), 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W., Bovin, M. J., Lee, D. J., Sloan, D. M., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Participant (N = 110), No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 39.40 (7.22) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 22 (20) |

| Men | 88 (80) |

| Married | 79 (72) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| African American | 31 (28) |

| Hispanic | 29 (26) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 42 (38) |

| Other | 4 (4) |

| Education | |

| ≤Some college | 48 (44) |

| ≥Associate degree | 62 (56) |

| Active duty | 75 (68) |

| Army | 88 (80) |

| Time in military, mean (SD), y | 15.22 (6.51) |

| Occupational Specialty | |

| Combat arms | 44 (40) |

| Combat support | 31 (28) |

| Combat service support | 34 (31) |

| Deployments, No. | |

| 1 | 27 (25) |

| 2 | 33 (30) |

| 3 | 23 (21) |

| ≥4 | 26 (24) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buccellato, K.H.; Straud, C.L.; Blount, T.H.; Evans, W.R.; Hein, J.M.; Santos, E.; Hale, W.J.; Foa, E.B.; Brown, L.A.; McLean, C.P.; et al. Examination of the Top Three Traumatic Experiences Among United States Service Members and Veterans with Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091211

Buccellato KH, Straud CL, Blount TH, Evans WR, Hein JM, Santos E, Hale WJ, Foa EB, Brown LA, McLean CP, et al. Examination of the Top Three Traumatic Experiences Among United States Service Members and Veterans with Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091211

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuccellato, Kiara H., Casey L. Straud, Tabatha H. Blount, Wyatt R. Evans, Jennifer M. Hein, Elizabeth Santos, Willie J. Hale, Edna B. Foa, Lily A. Brown, Carmen P. McLean, and et al. 2025. "Examination of the Top Three Traumatic Experiences Among United States Service Members and Veterans with Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091211

APA StyleBuccellato, K. H., Straud, C. L., Blount, T. H., Evans, W. R., Hein, J. M., Santos, E., Hale, W. J., Foa, E. B., Brown, L. A., McLean, C. P., Schobitz, R. P., DeBeer, B. B., Mignogna, J., Fina, B. A., Hall-Clark, B. N., Schrader, C. C., Yarvis, J. S., Jacoby, V. M., Lara-Ruiz, J. M., ... Peterson, A. L., on behalf of the The Consortium to Alleviate PTSD. (2025). Examination of the Top Three Traumatic Experiences Among United States Service Members and Veterans with Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091211