Time, Ideologies, and Care: Gendered Patterns of Parental Involvement in the UK and Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gender Ideologies, Biological Essentialism, and the Division of Paid Work and Childcare

1.2. Navigating Paid Work and Childcare in the UK and Portugal

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

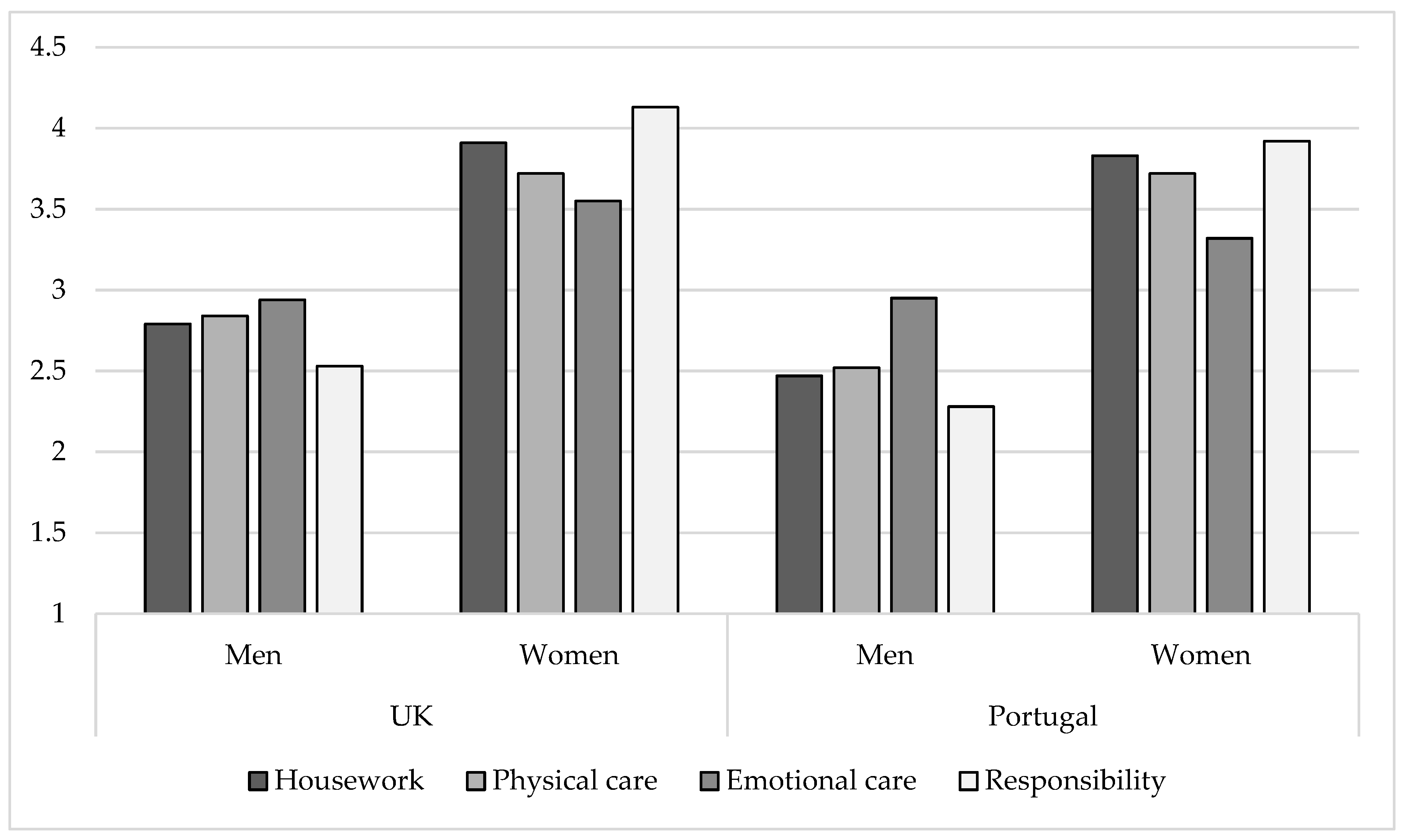

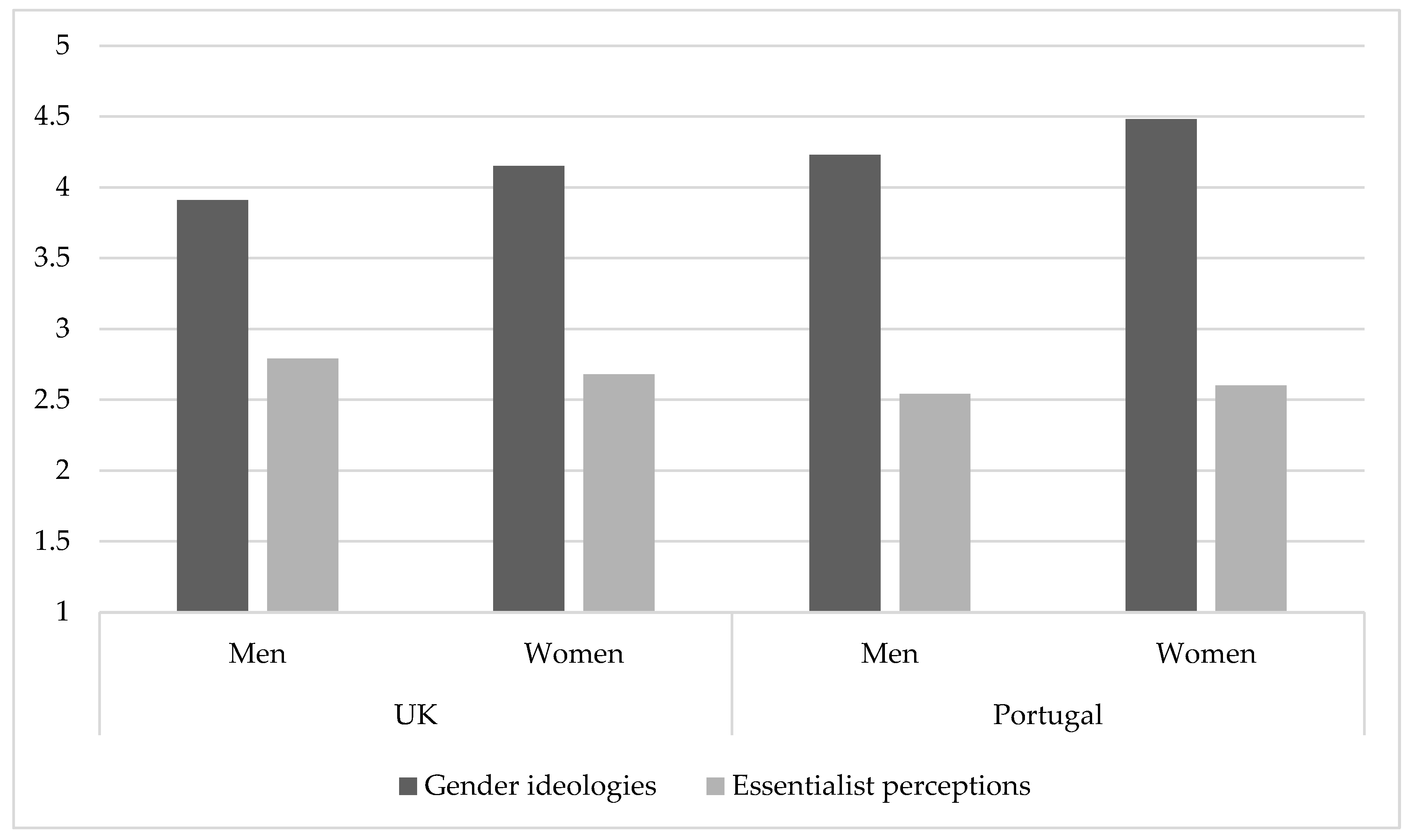

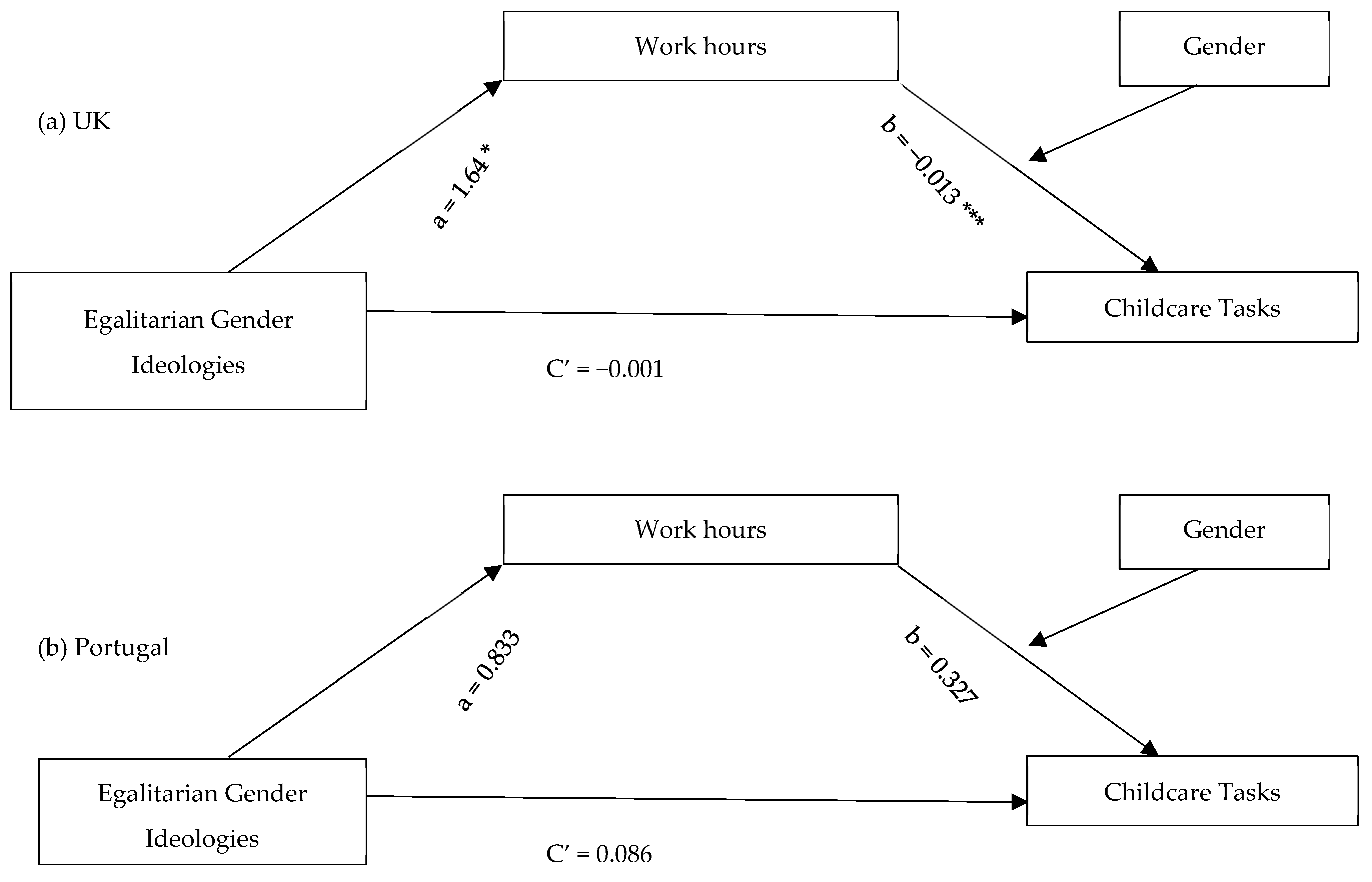

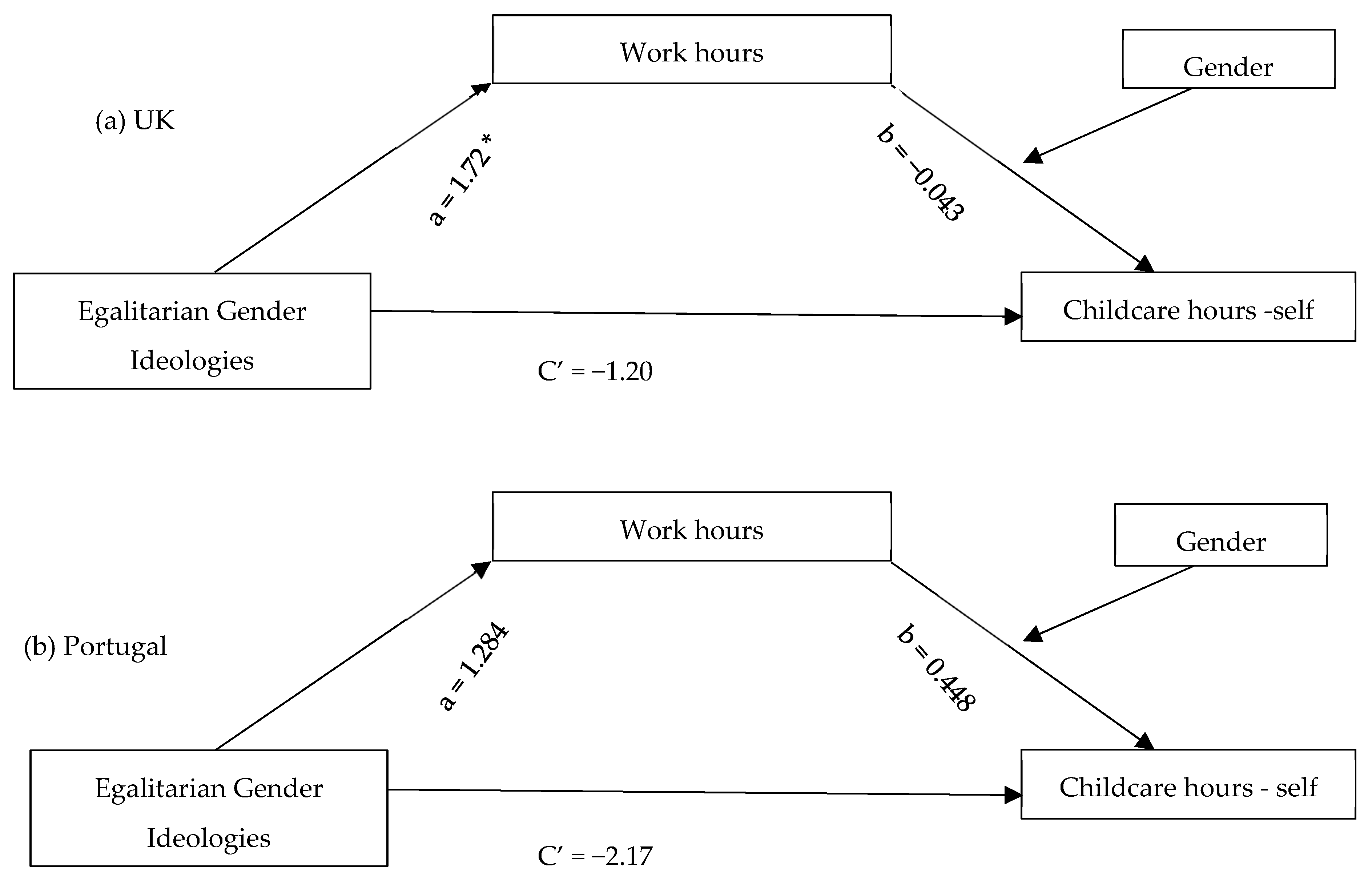

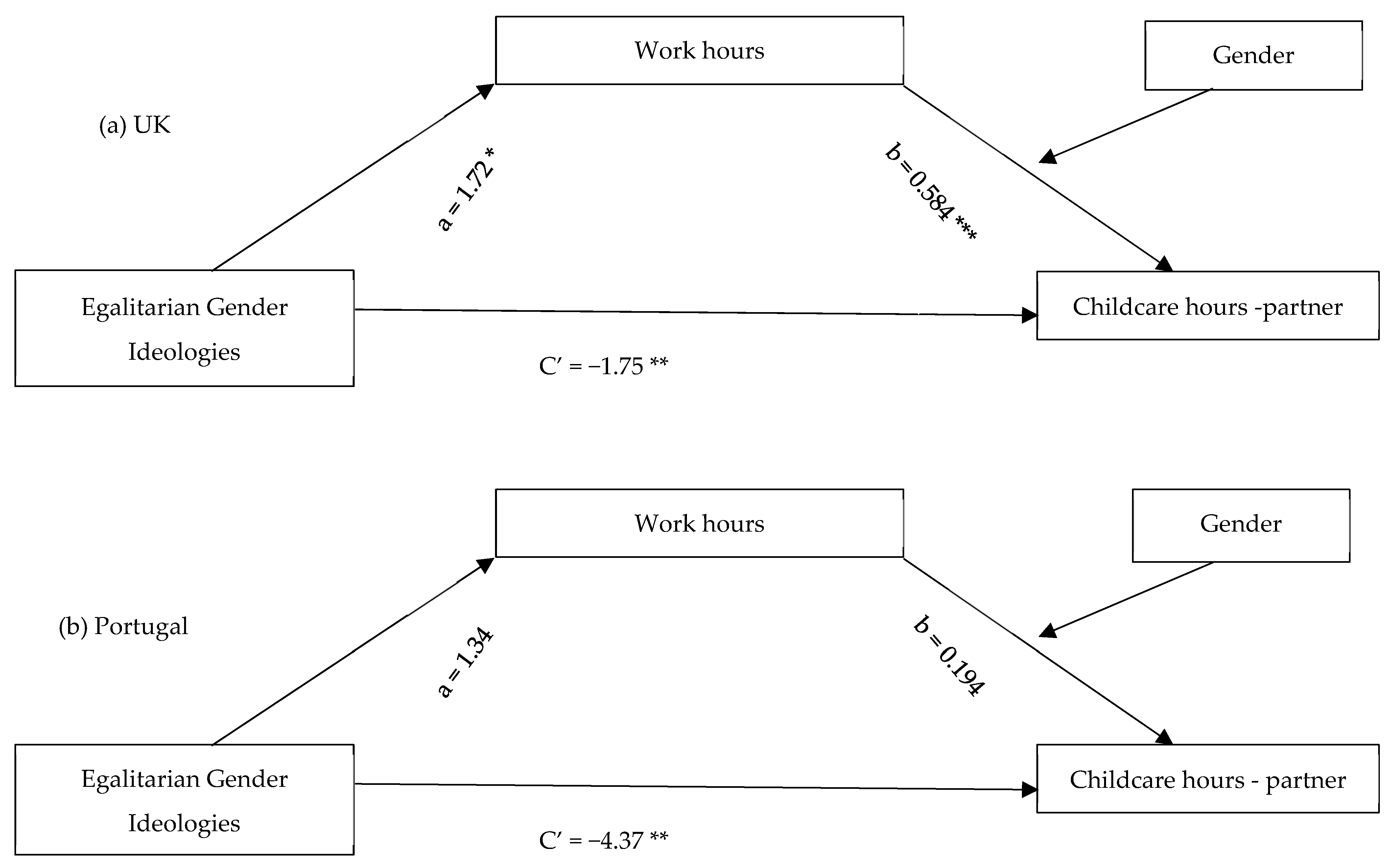

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Policy Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, J., & Stevenson, I. (2023). Gender roles. British social attitudes 40. National Centre for Social Research. Available online: https://natcen.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-09/BSA%2040%20Gender%20roles.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Altintas, E., & Sullivan, O. (2016). Fifty years of change updated: Cross-national gender convergence in housework. Demographic Research, 35, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendall, C., & Mitchell, G. (2023). The shared parental leave framework: Failing to fit working-class families? Journal of Social Policy, 52(3), 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornatici, C., & Zinn, I. (2025). Beyond tradition? How gender ideology impacts employment and family arrangements in Swiss couples. Gender & Society, 39(1), 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünning, M. (2020). Paternal part-time employment and fathers’ long-term involvement in child care and housework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 566–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., Birkett, H., Forbes, S., & Seo, H. (2021). Covid-19, Flexible working, and implications for gender equality in the United Kingdom. Gender & Society, 35(2), 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton-Sprigg, J., Fichera, E., Jones, M., & Kaya, E. (2024, September). Shared parental leave: Did it work? Evaluating the impact of the shared parental leave policy in the United Kingdom (IPR Policy Brief). University of Bath Institute for Policy Research. Available online: https://www.bath.ac.uk/publications/shared-parental-leave-did-it-work/attachments/shared-parental-leave-did-it-work-policy-brief(2).pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Coleman, L., Shorto, S., & Ben-Galim, D. (2022). Childcare survey 2022. Available online: https://www.familyandchildcaretrust.org/sites/default/files/Resource%20Library/Final%20Version%20Coram%20Childcare%20Survey%202022_0.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R., & Parodi, F. (2020). The gender pay gap in the UK: Children and experience in work. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(4), 855–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, V., & Atalaia, S. (2019). The Gender(ed) Division of labour in Europe: Patterns of practices in 18 EU countries. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 90, 113–137. Available online: https://revistas.rcaap.pt/sociologiapp/article/view/15526/14022 (accessed on 8 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M. (2008). Changing attitudes toward the male breadwinner, female homemaker family model: Influences of women’s employment and education over the lifecourse. Social Forces, 87(1), 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, F. M. (1999). Halving it all: How equally shared parenting works. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, F. M., & Gaunt, R. (2020). Creating equality at home: How 25 couples around the globe share housework and childcare. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. (2021). Part-time employment (%), by gender, 2018. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/all/european-jobs-monitor-2021-gender-gaps-and-employment-structure#data (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Eurofound. (2024). Working life in Portugal. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/resources/article/2024/working-life-portugal (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- European Commission [EC]. (2024). Portugal: Early childhood education and care national information sheet. Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/eurypedia/portugal/early-childhood-education-and-care (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- European Institute for Gender Equality [EIGE]. (2024). Gender equality index—Portugal. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2024/domain/work/PT/family (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Eurostat. (2025). Children cared only by their parents by age group—% over the population of each age group. Eurostat. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J. (2007). Displaying families. Sociology, 41(1), 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, R. (2006). Biological essentialism, gender ideologies, and role attitudes: What determines parents’ involvement in childcare. Sex Roles, 55(7–8), 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, R., & Deutsch, F. M. (2024). Mother’s instinct? Biological essentialism and parents’ involvement in work and childcare. Sex Roles, 90(2), 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, R., Jordan, A., Tarrant, A., Chanamuto, N., Pinho, M., & Wezyk, A. (2022). Caregiving dads, breadwinning mums: Transforming gender in work and childcare? Available online: https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Caregiving-Dads-Breadwinning-Mums-Full-Report-September-2022.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Gaunt, R., & Pinho, M. (2018). Do sexist mothers change more diapers? Ambivalent sexism, maternal gatekeeping and the division of childcare. Sex Roles, 79(3–4), 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, R., & Scott, J. (2014). Parents’ involvement in childcare: Do parental and work identities matter? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, B. (2022). The new dad: The career-caregiving conundrum. In M. Grau Grau, M. las Heras Maestro, & H. Riley Bowles (Eds.), Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality (pp. 197–212). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Vol. 3). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hook, J. L. (2006). Care in context: Men’s unpaid work in 20 countries, 1965–2003. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R. M., Johnson, M. D., Galambos, N. L., & Krahn, H. J. (2018). Time, money, or gender? Predictors of the division of household labour across life stages. Sex Roles, 78(11–12), 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, A. H., Olson, K. J., O’Gara, T. C., Jr., & King, E. B. (2014). Gender role beliefs and fathers’ work-family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(7), 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joecks, J., Kurowska, A., Pull, K., & Schober, P. (2024). Multidimensional gender ideologies: How do they relate to work-family arrangements of mothers with dependent children in Poland and western Germany? European Sociological Review, 40(5), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D., & Offer, S. (2022). Masculinity ideologies, sensitivity to masculinity threats, and fathers’ involvement in housework and childcare among US employed fathers. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 23(4), 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C. R., & Brinton, M. C. (2017). One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. American Journal of Sociology, 122(5), 1485–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbas, E., & Stanfors, M. (2023). Does caring for parents take its toll? Gender differences in caregiving intensity, coresidence, and psychological well-being across Europe. European Journal of Population, 39(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsæther, P. E., & Knutsen, C. H. (2024). Are women more progressive than men? Attitudinal gender gaps in West European democracies. International Political Science Review, 46(3), 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes da Silva, L., Marques, I., Mata, L., & Rosa, M. (2016). Orientações curriculares para a educação pré-escolar [Curriculum guidelines for preschool education]. Ministério da Educação/Direção-Geral da Educação (DGE). Available online: http://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Noticias_Imagens/ocepe_abril2016.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Monteiro, L., Fernandes, M., & Veríssimo, M. (2017). Father’s involvement and parenting styles in Portuguese families: The role of education and working hours. Análise Psicológica, 35(4), 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negraia, D. V., Augustine, J. M., & Prickett, K. C. (2018). Gender disparities in parenting time across activities, child ages, and educational groups. Journal of Family Issues, 39(11), 3006–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, H., & Elliot, M. (2015). Measuring paternal involvement in childcare and housework. Sociological Research Online, 20(2), 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. (2024). Gender pay gap in the UK: 2024. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2024 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. (2012). Quality matters in early childhood education and care: Portugal 2012. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D., Curtice, J., Phillips, M., & Perry, J. (2018). British social attitudes: The 35th report. The National Centre for Social Research. Available online: https://natcen.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-08/bsa35_full-report.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Pinho, M., & Gaunt, R. (2021). Doing and undoing gender in male carer/female breadwinner families. Community, Work & Family, 24(3), 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M., Lourenço, I., & Lousada, M. (2025). Who does what? The distribution of housework and childcare in Portuguese families. Genealogy, 9(2), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risman, B. J., Myers, K., & Sin, R. (2018). Limitations of the neoliberal turn in gender theory: (Re)turning to gender as a social structure. In J. W. Messerschmidt, P. Y. Martin, M. A. Messner, & R. Connell (Eds.), Gender reckonings: New social theory and research (pp. 277–296). New York University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlen, A. B., McKelley, R. A., & Whittaker, T. A. (2010). Stay-at-home fathers’ reasons for entering the role and stigma experiences: A preliminary report. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11(4), 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., & Fagan, J. (2020). The evolution of fathering research in the 21st century: Persistent challenges, new directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, O., Gershuny, J., & Robinson, J. P. (2018). Stalled or uneven gender revolution? A long-term processual framework for understanding why change is slow. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsen, K., Parks-Stamm, E. J., Kvalø, M., Olsen, M., & Martiny, S. E. (2022). Mothers’ domestic responsibilities and well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: The moderating role of gender essentialist beliefs about parenthood. Sex Roles, 87(1–2), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lippe, T., Treas, J., & Norbutas, L. (2018). Unemployment and the division of housework in Europe. Work, Employment & Society, 32(3), 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I. Y., & Cheung, R. Y. (2023). Parents’ gender role attitudes and child adjustment: The mediating role of parental involvement. Sex Roles, 89, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavorsky, J. E., Dush, C. M., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2015). The production of inequality: The gender division of Labor across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 77(3), 662–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| UK (n = 1049) | Portugal (n = 155) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers (n = 492) | Fathers (n = 557) | Mothers (n = 80) | Fathers (n = 75) | |

| Number of children | ||||

| 1 | 28.7% | 31.3% | 40% | 41.3% |

| 2 | 52% | 50.6% | 51.2% | 42.7% |

| 3–5 | 18.1% | 17.5% | 8.8% | 16% |

| 6–9 | 1.2% | 0.6% | 0% | 0% |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0% | 1.4% |

| 25–34 | 25.8% | 16.6% | 26.3% | 16.2% |

| 35–44 | 68.7% | 63.2% | 69.8% | 61.8% |

| 45–54 | 4.8% | 16.8% | 3.9% | 20.6% |

| 55+ | 0.4% | 3.1% | 0% | 0% |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 5.5% | 8.1% | 5.1% | 20% |

| High school diploma | 21.4% | 18.1% | 17.9% | 18.7% |

| Some college education | 2.3% | 0.79% | 7.7% | 6.7% |

| Academic degree | 70.8% | 73% | 69.3% | 54.6% |

| Monthly personal income | ||||

| ≤GBP 590 | 15.4% | 3.6% | 2.6% | 4.1% |

| GBP 591–GBP 1450 | 34.5% | 11.3% | 71.4% | 53.4% |

| GBP 1451–GBP 2600 | 32.6% | 43.8% | 11.7% | 11% |

| GBP 2601–GBP 3740 | 11.3% | 24.6% | 6.5% | 17.8% |

| ≥GBP 3741 | 6.2% | 16.7% | 7.8% | 13.7% |

| Mediation by Work Hours | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Moderated Mediation | |||||||

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||||

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | Estimate | Lower | Upper | Estimate | Lower | Upper | |

| UK | |||||||||

| Childcare tasks | −0.075 *** | −0.133 | −0.024 | −0.025 | −0.056 | 0.004 | −0.050 | −0.115 | 0.003 |

| Childcare hours—self | −0.752 *** | −1.56 | −0.098 | −0.413 *** | −0.084 | −0.059 | −0.339 | −0.976 | 0.004 |

| Childcare hours—partner | 0.313 *** | 0.182 | 0.732 | 0.660 *** | 0.093 | 1.26 | −0.347 *** | −0.689 | −0.042 |

| Portugal | |||||||||

| Childcare tasks | −0.006 | −0.059 | 0.019 | 0.002 | −0.014 | 0.021 | −0.008 | −0.067 | 0.021 |

| Childcare hours—self | −0.540 | −2.74 | 0.468 | 0.018 | −0.862 | 0.601 | −0.558 | −2.82 | 0.758 |

| Childcare hours—partner | −0.299 | −2.28 | 0.382 | −0.019 | −0.984 | 0.488 | −0.279 | −2.16 | 0.798 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinho, M.; Lourenço, I.; Lousada, M. Time, Ideologies, and Care: Gendered Patterns of Parental Involvement in the UK and Portugal. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091204

Pinho M, Lourenço I, Lousada M. Time, Ideologies, and Care: Gendered Patterns of Parental Involvement in the UK and Portugal. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091204

Chicago/Turabian StylePinho, Mariana, Inês Lourenço, and Marisa Lousada. 2025. "Time, Ideologies, and Care: Gendered Patterns of Parental Involvement in the UK and Portugal" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091204

APA StylePinho, M., Lourenço, I., & Lousada, M. (2025). Time, Ideologies, and Care: Gendered Patterns of Parental Involvement in the UK and Portugal. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1204. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091204