The Effect of Leadership Styles and Relational Contracts on Compensation Effectiveness and Employee Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Research Hypotheses, and Conceptual Model

2.1. Relational Contracts and Compensation System Effectiveness

2.2. Relational Contracts, Compensation System Effectiveness, and Mediating Role of Fairness Outcome and Intrinsic Motivation

2.3. Leadership Styles as Antecedents of Relational Contracts

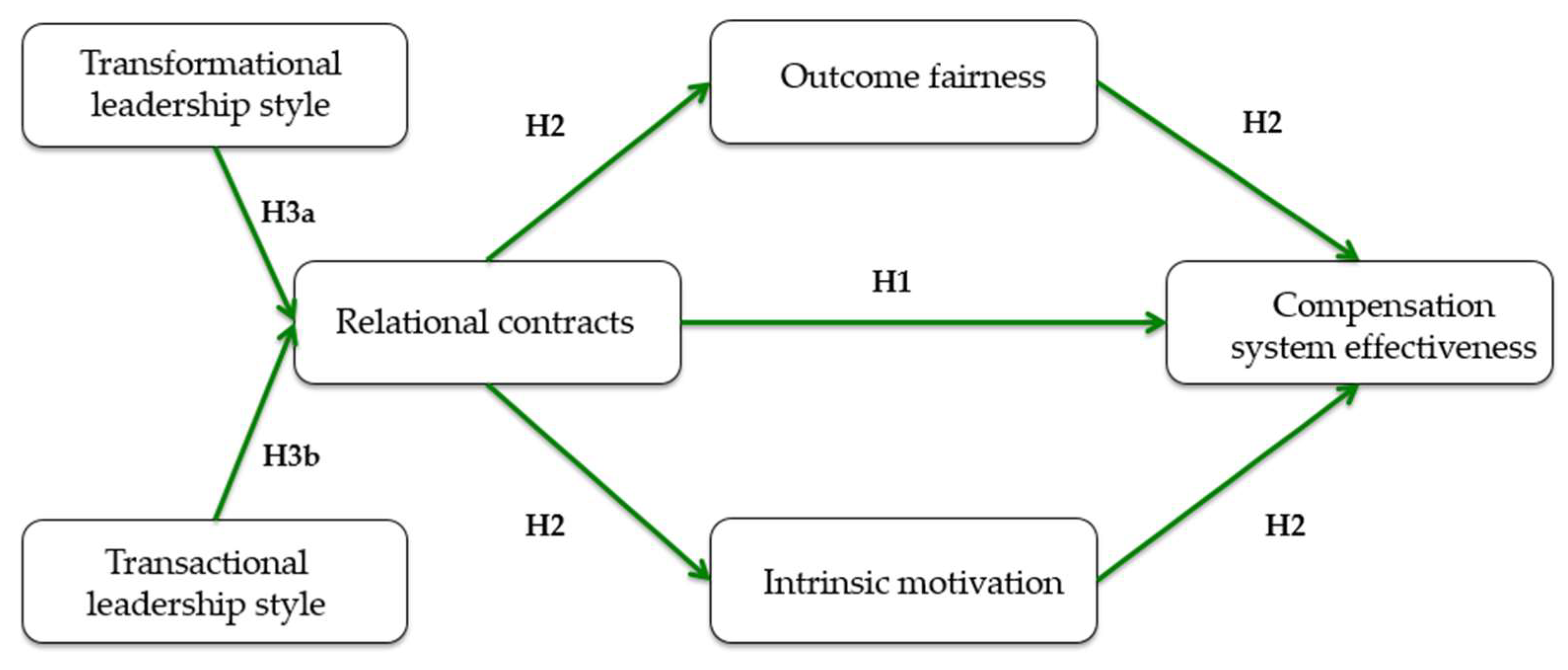

2.4. The Conceptual Model

3. Method

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Compensation System Effectiveness

3.2.2. Relational Contracts

3.2.3. Fairness Outcome

3.2.4. Intrinsic Motivation

3.2.5. Leadership Styles

3.2.6. Control Variables

3.3. Methodological Approach of Hypotheses Testing

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Hypothesis Tests

Full Test of the Theoretical Model Using Structural Equation Model

4.3. Supplemental Analyses

5. Implications and Limitations

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scale | Cronbach Alpha | Components |

|---|---|---|

| A Relational contracts | 0.78 | A1. I expect to gain promotion in this company with length of service and effort to achieve goals. A2. I expect to grow in this organization. A3. I feel part of a team in this organization A4. I feel this company reciprocates the effort put in by its employees. A5. I have a reasonable chance of promotion if I work hard. A6. I will work for this company indefinitely. A7. I am heavily involved in my place of work. |

| B Fairness outcome | 0.87 | B1. I think that rewards are relative to effort. B2. I think that rewards are relative to responsibilities. B3. I think that rewards are relative to job stress. B4. I think that rewards are relative to education and training. |

| C Intrinsic motivation | 0.86 | C1. The tasks that I do at work themselves represent a driving power in my job. C2. The tasks that I do at work are enjoyable. C3. My job is meaningful. C4. My job is very exciting. C5. My job is so interesting that it is a motivation in itself. C6. Sometimes I become so inspired by my job that I almost forget everything else around me. |

| D Compensation system effectiveness | 0.86 | D1. Our pay policies and practices are highly effective. D2. Management is satisfied with the way the compensation system contributes to the achievement of overall organizational goals. D3. Our pay policies and practices appear to enjoy widespread acceptability among employees. D4. Our pay policies and practices greatly contribute to the retention of employees. D5. Our pay policies and practices greatly contribute to the attraction of employees. D6. Our pay policies and practices greatly contribute to the motivation of employees. |

| E Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | 0.92 | E1. My branch manager makes others feel good to be around him/her. E2. My branch manager expresses with a few simple words what we could and should do. E3. My branch manager enables others to think about old problems in new ways. E4. My branch manager helps others develop themselves. E5. My branch manager tells others what to do if they want to be rewarded for their work. E6. My branch manager is satisfied when others meet agreed-upon standards. E7. My branch manager is content to let others continue working in the same ways always. E8. Others from the branch have complete faith in our branch manager. E9. My branch manager provides appealing images about what we can do. E10. My branch manager provides others with new ways of looking at puzzling things. E11. My branch manager lets others know how he/she thinks they are doing. E12. My branch manager provides recognition/rewards when others reach their goals. E13. As long as things are working, my branch manager does not try to change anything. E14. Whatever others want to do is OK with my branch manager. E15. Others are proud to be associated with my branch manager. E16. My branch manager helps others find meaning in their work. E17. My branch manager gets others to rethink ideas that they had never questioned before. E18. My branch manager gives personal attention to others who seem rejected. E19. My branch manager calls attention to what others can get for what they accomplish. E20. My branch manager tells others the standards they have to know to carry out their work. E21. My branch manager asks no more of others than what is absolutely essential. |

| Variable | Category/Description |

|---|---|

| Sex | Female (81) |

| Male (25) | |

| Age | Mean = 37.50 (SD = 6.70) |

| Work Experience | Mean = 10.12 years (SD = 5.05) |

| Branch Size | Mean = 14.2 employees (SD = 8.13) |

| Number of Branches | 24 branches across 5 major cities in Serbia |

| Main Location | Majority in Belgrade; balanced across municipalities |

| Eligibility Criteria | ≥5 employees per branch, ≥1 year in current position |

| Response Rate | 106 usable responses out of 206 distributed |

| 1 | This paper employes the definitions of transactional and transformational leadership styles as per McDermott et al. (2013). Specifically, transactional leaders often use particular, measurable goals, coordinating the work and monitoring accomplishments and deliverables of their team, while transformational leaders operate by inspiring people, linking results to values and fostering common goals and mutual identification. |

| 2 | These systems are used in many organizations and are often referred to as forced rankings, forced distributions, or rank-and-yank systems where people are ranked on a bell curve or other pre-defined distribution. |

| 3 | Employee salary comprises two parts: a basic salary and a bonus. Managers suggest the allocation of the bonus pool between employees; the decision is based on employee performance. The basic salary is pre-defined for all positions in the bank, and managers have no influence on that part of the compensation. |

| 4 | All employees gave their written consent before the survey, stressing the purpose of the study and confidentially of their participation. We emphasized anonymity to top management, employees, and branch managers to assure them that answers of employees would be treated with confidentiality. The intention was to obtain answers that reflect the genuine opinion of the employee. To further promote the survey among employees, we offered the top management team to discuss anonymized results in an anonymized report, once the study was completed. |

| 5 | We run an independent-sample t-test in order to compare the responses from branches we visit early versus responses from branches we visit late (Lindner et al., 2001). In order to do so, we split the dataset into two groups. The first group contains the first 25% of the responses, and the second contains the 25% of the responses collected at the end. Results show that there is not a statistically significant difference in the mean compensation system effectiveness scores for early and late responses [t(56) = −1.102, p = 0.28]. |

References

- Abernethy, M. A., Bouwens, J., & Kroos, P. (2017). Organization identity and earnings manipulation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 58, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernethy, M. A., Bouwens, J., & Van Lent, L. (2010). Leadership and control system design. Management Accounting Research, 21(1), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U. A., & Gupta, R. K. (2018). Examining the nature and effects of psychological contract: Case study of an Indian organization. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblooshi, M., Shamsuzzaman, M., & Haridy, S. (2021). The relationship between leadership styles and organisational innovation: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(2), 338–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rabiey, A. S. F., Al-Ghaili, M., Algomaie, M. M. A., & Ghanem, S. M. A. (2024). The impact of employee relation management and transformational leadership on employee performance. International Journal of Research, 11(3), 114–134. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, D. A. (2019). The effect of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behavior: The role of trust in leader as a mediation and perceived organizational support as a moderation. Journal of Leadership in Organizations, 1(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ariasa, D., Oktini, D. R., Respati, T., & Adwiyah, R. (2024). The influence of transformational leadership and organizational justice toward organizational commitment (A case study of employees at X Principal Clinic and Laboratory in Bandung). Journal of Management and Economic Studies, 6(4), 455–475. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Attahiru, M. S. (2021). The impact of compensation system on employee performance: The Islamic perspectives. International Journal of Intellectual Discourse, 4(4), 139–151. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (1988). Transformational leadership, charisma, and beyond. In Emerging leadership vistas (pp. 29–49). Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (1995). Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G., Gibbons, R., & Murphy, K. J. (2002). Relational contracts and the theory of the firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 39–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkin, D. B., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (1990). Matching compensation and organizational strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 11(2), 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, D. S., Malmi, T., & Sandelin, M. (2016). Management control effectiveness and strategy: An empirical analysis of packages and systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 51, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J., Harbring, C., & Sliwka, D. (2013). Performance appraisals and the impact of forced distribution—An experimental investigation. Management Science, 59(1), 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, F., & O’Driscoll, M. P. (2011). Psychological ownership in small family-owned businesses: Leadership style and nonfamily-employees’ work attitudes and behaviors. Group & Organization Management, 36(3), 345–384. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, E. C., Brockner, J., Van den Bos, K., Seifert, M., Moon, H., van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2015). Trust in decision-making authorities dictates the form of the interactive relationship between outcome fairness and procedural fairness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R. C. (2005). Employment as a relational contract. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment Law, 8, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, B. D., Baldwin, T. T., & Rubin, R. S. (2009). Reactions to different types of forced distribution performance evaluation systems. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, J. C. (2011). The determinants and performance effects of managers’ performance evaluation biases. The Accounting Review, 86(5), 1549–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, J. C., & Lill, J. B. (2015). Performance target revisions in incentive contracts: Do information and trust reduce ratcheting and the ratchet effect? The Accounting Review, 90(5), 1755–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwens, J., Cardinaels, E., & Zhang, J. (2020). The history of performance: How franchisor and franchisees signal their future actions in targets and performance. SSRN 2617406. SSRN. [Google Scholar]

- Braganza, A., Chen, W., Canhoto, A., & Sap, S. (2021). Productive employment and decent work: The impact of AI adoption on psychological contracts, job engagement and employee trust. Journal of Business Research, 131, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camanho, A. S., & Dyson, R. G. (1999). Efficiency, size, benchmarks and targets for bank branches: An application of data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 50(9), 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. P. (2012). Behavior, performance, and effectiveness in the twenty-first century. In The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 159–194). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. (2021). The interplay between relational and transactional psychological contracts and burnout and engagement. Asia Pacific Management Review, 26(1), 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K., Kuo, C. C., Stan, O. M., & Huang, C. F. (2025). Do challenging jobs make employees feel better or worse? Two types of psychological contract have the answer. International Journal of Organizational Analysis (IJOA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, R. (2019). Impact of forced distribution system of performance evaluation on organizational citizenship behaviour. Global Business Review, 20(3), 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. X., & Aryee, S. (2007). Delegation and employee work outcomes: An examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J., Pádua, M., & Moreira, A. C. (2023). Leadership styles and innovation management: What is the role of human capital? Administrative Sciences, 13(2), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J., & Kessler, I. (2000). Consequences of the psychological contract for the employment relationship: A large scale survey. Journal of Management Studies, 37(7), 903–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrington, J. W., & Howell, G. A. (2011). Motivation and incentives in relational contracts. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 16(1), 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D. N., Van Muijen, J. J., & Koopman, P. L. (1997). Transactional versus transformational leadership: An analysis of the MLQ. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, F., & Safaria, S. (2025). The effect of conflict management, work motivation and work environment on the performance of AO Mekaar PT Permodalan Nasional Madani Karo area with job satisfaction as an intervening variable. Formosa Journal of Sustainable Research, 4(4), 793–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, K. R., & Stichler, J. F. (2008). Manager and staff perceptions of the manager’s leadership style. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 38(11), 480–487. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, E., Klein, A., & Schmidt, K. M. (2007). Fairness and contract design. Econometrica, 75(1), 121–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbach, A., & Woolley, K. (2022). The structure of intrinsic motivation. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9(1), 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachter, S., Renner, E., & Sefton, M. (2008). The long-run benefits of punishment. Science, 322(5907), 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). Self-determination theory applied to work motivation and organizational behavior. In The SAGE handbook of industrial, work & organizational psychology: Organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 97–121). Sage Reference. [Google Scholar]

- Gallani, S., Krishnan, R., Marinich, E. J., & Shields, M. D. (2019). Budgeting, psychological contracts, and budgetary misreporting. Management Science, 65(6), 2924–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R., & Henderson, R. (2012). Relational contracts and organizational capabilities. Organization Science, 23(5), 1350–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R., & Kaplan, R. S. (2015). Formal measures in informal management: Can a balanced scorecard change a culture? American Economic Review, 105(5), 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M., Merchant, K. A., Stede, W. A. V. D., & Vargus, M. E. (2004). Determinants and effects of subjectivity in incentives. The Accounting Review, 79(2), 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M. J., Merchant, K. A., Stede, W. A. V. D., & Vargus, M. E. (2005). The benefits of evaluating performance subjectively. Performance Improvement, 44(5), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Welbourne, T. M. (1988). Compensation strategy: An overview and future steps. Human Resource Planning, 11(3), 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- González-Cánovas, A., Trillo, A., Bretones, F. D., & Fernández-Millán, J. M. (2024). Trust in leadership and perceptions of justice in fostering employee commitment. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1359581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafton, J., & Mundy, J. (2017). Relational contracting and the myth of trust: Control in a co-opetitive setting. Management Accounting Research, 36, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M., & Oddy, M. (2007). Violation of the psychological contract: The mediating effect of relational versus transactional beliefs. Australian Journal of Management, 32(1), 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, R. C. (2005). Forced ranking: Making performance management work. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, D. (2004). Flexible employment contracts, the psychological contract and employee outcomes: An analysis and review of the evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N., & Shaw, J. D. (2014). Employee compensation: The neglected area of HRM research. Human Resource Management Review, 24(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, F., Naranjo-Gil, D., & Perego, P. (2010). The effects of leadership styles and use of performance measures on managerial work-related attitudes. European Accounting Review, 19(2), 275–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herriot, P., & Pemberton, C. (1996). Contracting careers. Human Relations, 49(6), 757–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, B., & Milgrom, P. (1994). The firm as an incentive system. The American Economic Review, 972–991. [Google Scholar]

- Hutama, A. A., Noermijati, N., & Irawanto, D. W. (2024). The effect of transactional leadership on employee performance mediated by job satisfaction, job stress and trust. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 13(3), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1992). Specific and general knowledge and organizational structure. In Contract Economics (pp. 252–274). Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K. H. (2005). The relation among fit indexes, power, and sample size in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(3), 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (1998). Structural equation modeling (33p). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, V. R. (2001). Value systems of transformational leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 22(3), 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, B., Buch, R., Weibel, A., Dysvik, A., & Nerstad, C. G. (2017). Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation relate differently to employee outcomes? Journal of Economic Psychology, 61, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C. M., & Oger, B. (2012). Behavioral effects of fairness in performance measurement and evaluation systems: Empirical evidence from France. Advances in Accounting, 28(2), 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E. E., III. (1990). Strategic pay: Aligning organizational strategies and pay systems. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. C., Yeh, W. C., Yu, Z., & Lin, X. C. (2023). The relationships between leader emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and transactional leadership and job performance: A mediator model of trust. Heliyon, 9(8), e18007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. K., Tackett, S., Skarupski, K. A., Forbush, K., Fivush, B., Oliva-Hemker, M., & Levine, R. B. (2024). Inspiring and preparing our future leaders: Evaluating the impact of the early career women’s leadership program. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. (2003). Relational incentive contracts. American Economic Review, 93(3), 835–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, J. R., Murphy, T. H., & Briers, G. E. (2001). Handling nonresponse in social science research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(4), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, J., & Shields, M. D. (2003). Mapping management accounting: Graphics and guidelines for theory-consistent empirical research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2–3), 169–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, A. M., Conway, E., Rousseau, D. M., & Flood, P. C. (2013). Promoting effective psychological contracts through leadership: The missing link between HR strategy and performance. Human Resource Management, 52(2), 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, K. J., Meyer, J. P., & Feldman, S. (2009). Psychological contracts and their implications for commitment: A feature-based approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, L. J., & Hopkins, L. J. (1998). Psychological contracts, organizational and job commitment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(16), 1530–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. J. (2013). Executive compensation: Where we are, and how we got there. In Handbook of the economics of finance (Vol. 2, pp. 211–356). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Olley, R. (2021). A focussed literature review of power and influence leadership theories. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 16(2), 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorschot, J., Moscardo, G., & Blackman, A. (2021). Leadership style and psychological contract. Australian Journal of Career Development, 30(1), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterloh, M., Frost, J., & Frey, B. S. (2002). The dynamics of motivation in new organizational forms. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 9(1), 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasamar, S., Diaz-Fernandez, M., & de La Rosa-Navarro, M. D. (2019). Human capital: The link between leadership and organizational learning. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 28(1), 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, C. L., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(2), 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A., Hilton, S. K., & Quao, B. (2020). The interaction effect of transactional-transformational leadership on employee commitment in a developing country. Management Research Review, 44(3), 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, U., Johns, G., & Ntalianis, F. (2004). The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotemberg, J. J., & Saloner, G. (1993). Leadership style and incentives. Management Science, 39(11), 1299–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Psychological contracts in the workplace: Understanding the ties that motivate. Academy of Management Perspectives, 18(1), 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. M., & McLean Parks, J. (1993). The contracts of individuals and organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 15, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2019). Brick by brick: The origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. In Advances in motivation science (Vol. 6, pp. 111–156). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R. S., & MacMillan, I. C. (1984). Gaining competitive advantage through human resource management practices. Human Resource Management, 23(3), 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L. M., & Tetrick, L. E. (1994). The psychological contract as an explanatory framework in the employment relationship. Trends in Organizational Behavior, 1(91), 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y., Zhou, H., & Choi, M. C. (2024). Differentiated empowering leadership and interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors: A chained mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, B., Klug, H. J., & Maier, G. W. (2018). The path is the goal: How transformational leaders enhance followers’ job attitudes and proactive behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S. M., Gruys, M. L., & Storm, M. (2010). Forced distribution performance evaluation systems: Advantages, disadvantages and keys to implementation. Journal of Management & Organization, 16(1), 168–179. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Syofyan, E., Hernando, R., & Septiari, D. (2021). The role of leadership style on evaluation fairness. AKRUAL: Jurnal Akuntansi, 13(1), 94–108. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tabernero, C., Chambel, M. J., Curral, L., & Arana, J. M. (2009). The role of task-oriented versus relationship-oriented leadership on normative contract and group performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 37(10), 1391–1404. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tuffour, J. K., Gali, A. M., & Tuffour, M. K. (2022). Managerial leadership style and employee commitment: Evidence from the financial sector. Global Business Review, 23(3), 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M. (2006). Relational leadership theory: Exploring the social processes of leadership and organizing. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 654–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2007). Leadership style, organizational politics, and employees’ performance: An empirical examination of two competing models. Personnel Review, 36(5), 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, L. D. (2020). Is stricter regulation of incentive compensation the missing piece? Journal of Banking Regulation, 21(1), 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T. B., Ho, T. C., Kelana, B. W. Y., Othman, R., & Syed, O. R. (2019). Leadership styles in influencing employees’ job performances. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(9), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yammarino, F. J., Spangler, W. D., & Bass, B. M. (1993). Transformational leadership and performance: A longitudinal investigation. The Leadership Quarterly, 4(1), 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolande, M. K. (2024). The impact of compensation and internal equity on employee performance. Open Journal of Accounting, 13(2), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||||

| Compensation system effectiveness | 3.18 | 0.65 | 1 | 4.67 | 0.86 |

| Independent variables—mediators | |||||

| Relational contracts | 3.88 | 0.62 | 1.43 | 5.00 | 0.78 |

| Transformational leadership style | 4.16 | 0.61 | 2 | 5 | 0.96 |

| Transactional leadership style | 2.93 | 0.79 | 1 | 5 | 0.71 |

| Fairness outcome | 3.17 | 1.01 | 1 | 5 | 0.87 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 3.57 | 0.71 | 1.67 | 5 | 0.86 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Experience | 10.12 | 5.05 | 1 | 30 | NA |

| Number of employees | 14.22 | 8.13 | 5 | 29 | NA |

| Long-term pay | 3.29 | 0.63 | 1 | 5 | 0.48 |

| Pay decentralization | 2.46 | 0.85 | 1 | 5 | 0.64 |

| Sex | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | NA |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Relational contracts | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 | Fairness outcome | 0.52 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 3 | Intrinsic motivation | 0.49 ** | 0.35 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 4 | Experience | −0.22 ** | −0.07 | −0.06 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | Number of employees | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.27 * | −0.09 | 1 | |||||

| 6 | Long term pay | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.19 * | −0.05 | 0.07 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | Pay decentralization | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.36 ** | 0.12 | 1 | |||

| 8 | Sex | 0.014 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.19 * | −0.07 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 1 | ||

| 9 | Transformational leadership style | 0.49 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.19 * | −0.20 * | 0.31 ** | −0.19 | 0.06 | 1 | |

| 10 | Transactional leadership style | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.19 * | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1 |

| 11 | Compensation system effectiveness | 0.38 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.53 ** | −0.03 | 0.25 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.21 ** |

| Models | (1) Compensation System Effectiveness | (2) Fairness Outcome | (3) Intrinsic Motivation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t | Sig. | Beta | t | Sig. | Beta | t | Sig. | |

| Relational contracts | 0.31 | 3.55 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 5.78 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 5.18 | 0.00 |

| Controls | |||||||||

| Experience | 0.07 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.54 |

| Number of employees | 0.18 | 1.97 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.73 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 2.83 | 0.01 |

| Long-term pay | 0.27 | 3.11 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 1.15 | 0.25 |

| Pay decentralization | 0.19 | 2.11 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 1.98 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.86 |

| Sex | −0.02 | −0.25 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

| Observations (n) | 106 | 106 | 106 | ||||||

| R-squared | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||||||

| Model | Compensation System Effectiveness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t | Sig. | |

| Relational contracts | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.43 |

| Outcome fairness | 0.15 | 1.63 | 0.11 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 0.33 | 3.55 | 0.00 |

| Controls | |||

| Experience | 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| Number of employees | 0.10 | 1.16 | 0.25 |

| Long term pay | 0.23 | 2.80 | 0.01 |

| Pay decentralization | 0.16 | 1.83 | 0.07 |

| Sex | −0.04 | −0.55 | 0.58 |

| Observations (n) | 106 | ||

| R-squared | 0.41 | ||

| Models | (1) Relational Contracts | (2) Relational Contracts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t | Sig. | Beta | t | Sig. | |

| Transformational leadership style | 0.54 | 5.61 | 0.00 | |||

| Transactional leadership style | −0.08 | −0.82 | 0.41 | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Experience | −0.10 | −1.17 | 0.24 | −0.22 | −2.23 | 0.03 |

| Number of employees | 0.13 | 1.38 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.68 |

| Long-term pay | −0.05 | −0.56 | 0.57 | 0.13 | 1.34 | 0.18 |

| Pay decentralization | 0.14 | 1.44 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.81 |

| Sex | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.73 |

| Observations (n) | 106 | 106 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.29 | 0.76 | ||||

| Panel A: Effect of ratings on performance outcomes (i.e., non-working hours) and impact of compensation effectiveness | ||||||

| Models | (1) Non-working hours | (2) Non-working hours | ||||

| Beta | t | Sig. | Beta | t | Sig. | |

| Ratings | −0.18 | −1.66 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 1.44 | 0.15 |

| Compensation system effectiveness | 0.71 | 1.56 | 0.12 | |||

| Compensation system effectiveness × Ratings | −1.21 | −1.81 | 0.07 | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Experience | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.48 |

| Number of employees | 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 0.40 |

| Long-term pay | 0.14 | 1.31 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.74 | 0.46 |

| Pay decentralization | 0.24 | 2.11 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 2.11 | 0.04 |

| Sex | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.84 | 0.40 |

| Observations (n) | 83 | 83 | ||||

| R-squared | 18.9% | 22.9% | ||||

| Panel B: Effects of ratings on performance outcomes (i.e., non-working hours) for low and high perceived compensation system effectiveness | ||||||

| Below the median value | Above the median value | |||||

| Models | (1) Non-working hours | (2) Non-working hours | ||||

| Beta | t | Sig. | Beta | t | Sig. | |

| Ratings | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.73 | −0.23 | −1.79 | 0.08 |

| Controls | ||||||

| Experience | 0.60 | 2.76 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.78 |

| Number of employees | 0.47 | 2.23 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.64 |

| Long-term pay | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.72 | 0.47 |

| Pay decentralization | 0.27 | 1.39 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 1.71 | 0.09 |

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.89 | 0.12 | 0.91 | 0.36 |

| Observations (n) | 22 | 61 | ||||

| R-squared | 43.4% | 20.5% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rakic, N.; Barjaktarovic Rakocevic, S. The Effect of Leadership Styles and Relational Contracts on Compensation Effectiveness and Employee Performance. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091201

Rakic N, Barjaktarovic Rakocevic S. The Effect of Leadership Styles and Relational Contracts on Compensation Effectiveness and Employee Performance. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091201

Chicago/Turabian StyleRakic, Nela, and Sladjana Barjaktarovic Rakocevic. 2025. "The Effect of Leadership Styles and Relational Contracts on Compensation Effectiveness and Employee Performance" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091201

APA StyleRakic, N., & Barjaktarovic Rakocevic, S. (2025). The Effect of Leadership Styles and Relational Contracts on Compensation Effectiveness and Employee Performance. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091201