Survivor Guilt as a Mediator Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Pessimism Schema After Türkiye-Syria Earthquake

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Difference Analysis

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadian, A., Mirzaee, J., Omidbeygi, M., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Brand, S. (2015). Differences in maladaptive schemas between patients suffering from chronic and acute posttraumatic stress disorder and healthy controls. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, J. A., Colvonen, P. J., Angkaw, A. C., & Norman, S. B. (2019). Differential relationships of guilt and shame on posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans. Psychol Trauma, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, A., Bär, H. E., Rijkeboer, M. M., & Lobbestael, J. (2023). Early maladaptive schemas and schema modes in clinical disorders: A systematic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(3), 716–747. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R., & Ranieri, W. F. (1996). Comparison of beck depression inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J. G., McNiff, J., Clapp, J. D., Olsen, S. A., Avery, M. L., & Hagewood, J. H. (2011). Exploring negative emotion in women experiencing intimate partner violence: Shame, guilt, and PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 42, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudoukha, A.-H., Przygodzki-Lionet, N., & Hautekeete, M. (2016). Traumatic events and early maladaptive schemas (EMS): Prison guard psychological vulnerability. European Review of Applied Psychology, 66, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysan, M., Guzel Ozdemir, P., Ozdemir, O., Selvi, Y., Yilmaz, E., & Kaya, N. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (PCL-5). Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, K. C., Trim, R. S., Myers, U. S., & Norman, S. B. (2015). Trauma-related guilt: Conceptual development and relationship with posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms. J Trauma Stress, 28, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bub, K., & Lommen, M. J. (2017). The role of guilt in posttraumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8, 1407202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadichon, J. M., Lignier, B., Cénat, J.-M., & Derivois, D. (2017). Symptoms of PTSD among adolescents and young adult survivors six years after the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 22, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Hankin, B. L. (2013). Early maladaptive schemas and social anxiety in adolescents: The mediating role of anxious automatic thoughts. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockram, D. M., Drummond, P. D., & Lee, C. W. (2010). Role and treatment of early maladaptive schemas in Vietnam Veterans with PTSD. Clin Psychol Psychother, 17, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arms, J., Jacobson, D., & Carlsson, A. (2022). The motivational theory of guilt (and its implications for responsibility). In Self-blame and moral responsibility (pp. 11–27). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso, L., Carmassi, C., Massimetti, G., Stratta, P., Riccardi, I., Capanna, C., Akiskal, K. K., Akiskal, H. S., & Rossi, A. (2013). Age, gender and epicenter proximity effects on post-traumatic stress symptoms in L’Aquila 2009 earthquake survivors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 146(2), 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, T., Smith, C., & Eagle, G. (2022). The trauma trilogy of catastrophic grief, survivor guilt and anger in aging child holocaust survivors. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 27, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fimiani, R., Gazzillo, F., Dazzi, N., & Bush, M. (2022). Survivor guilt: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical features. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 31(3), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, N., & Koh, E. (2022). Children’s survivor guilt after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami: A case report. Educational Psychology in Practice, 38, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzillo, F., Gorman, B., Bush, M., Silberschatz, G., Mazza, C., Faccini, F., Crisafulli, V., Alesiani, R., & De Luca, E. (2017). Reliability and validity of the Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale-15: A new clinician-reporting tool for assessing interpersonal guilt according to Control-Mastery Theory. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 45, 362–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt-Kimron, L., Karatzias, T., Yonatan, M., Shoham, A., Hyland, P., Ben-Ezra, M., & Shevlin, M. (2023). Early maladaptive schemas and ICD-11 CPTSD symptoms: Treatment considerations. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. University of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, K. R., & Frueh, B. C. (1997). Combat guilt and its relationship to PTSD symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapci, E. G., Uslu, R., Turkcapar, H., & Karaoglan, A. (2008). Beck depression inventory II: Evaluation of the psychometric properties and cut-off points in a Turkish adult population. Depression and Anxiety, 25, E104–E110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T., Jowett, S., Begley, A., & Deas, S. (2016). Early maladaptive schemas in adult survivors of interpersonal trauma: Foundations for a cognitive theory of psychopathology. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7, 30713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, K., Romaniuk, M., McLeay, S., Walker, S., Henderson, J., & Khoo, A. (2021). Guilt and it’s relationship to mental illness and suicide attempts in an Australian veteran population with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Military and Veterans Health, 29, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Keser, E., Ar-Karcı, Y., & Gökler Danısman, I. (2022). Validity and reliability study of Turkish forms of the quality of relationships inventory-bereavement version and the bereavement guilt scale. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 33, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kip, A., Diele, J., Holling, H., & Morina, N. (2022). The relationship of trauma-related guilt with PTSD symptoms in adult trauma survivors: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 52(12), 2201–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. A., Scragg, P., & Turner, S. (2001). The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: A clinical model of shame-based and guilt-based PTSD. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leys, R. (2009). From guilt to shame: Auschwitz and after. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, A. E. Z., Chooi, W. T., & Bono, S. A. (2023). A systematic review investigating the early maladaptive schemas (EMS) in Individuals with trauma experiences and PTSD. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(1), 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, L. B., Koch, E. I., Saules, K. K., & Jefferson, S. (2016). Exploratory factor analysis of diagnostic and statistical manual, 5th edition, criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G. A., Barrett, K. C., Leech, N. L., & Gloeckner, G. W. (2019). IBM SPSS for introductory statistics: Use and interpretation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, H., Pethania, Y., & Medin, E. (2021). Survivor guilt: A cognitive approach. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 14, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, H. L. (2018). Survivor guilt in a posttraumatic stress disorder clinic sample. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 23, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederland, W. G. (1968). Clinical observations on the “survivor syndrome”. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 49(2–3), 313–315. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, S., Allard, C., Browne, K., Capone, C., Davis, B., & Kubany, E. (2019). Trauma informed guilt reduction therapy: Treating guilt and shame resulting from trauma and moral injury. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., Weiss, J., Bush, M., & Sampson, H. (1997). Interpersonal guilt: The development of a new measure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perloff, T., King, J. C., Rigney, M., Ostroff, J. S., & Johnson Shen, M. (2019). Survivor guilt: The secret burden of lung cancer survivorship. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 37, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pethania, Y., Murray, H., & Brown, D. (2018). Living a life that should not be lived: A qualitative analysis of the experience of survivor guilt. Journal of Traumatic Stress Disorders and Treatment, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, V., & Swift, M. (2019). Building resilience from survivor guilt after a traumatic event. Crisis, Stress, and Human Resilience: An International Journal, 1, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, L. R., Taylor, P. J., & Berry, K. (2015). The role of guilt in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 182, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J., Yang, X., Tan, R., Wu, X., & Zhou, X. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among adolescents over 1 year after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders, 261, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resmi Gazete. (2023). Adana, Adıyaman, Diyarbakır, Gaziantep, Hatay, Kahramanmaraş, Kilis, Malatya, Osmaniye ve Şanlıurfa illerinde üç ay süreyle olağanüstü hali ilan edilmesine dair karar. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2023/02/20230210-1.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Sayed, S., Iacoviello, B. M., & Charney, D. S. (2015). Risk factors for the development of psychopathology following trauma. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(8), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soygüt, G., Karaosmanoğlu, A., & Çakir, Z. (2009). Erken dönem uyumsuz şemalarin değerlendirilmesi: Young şema ölçeği kisa form-3’ün psikometrik özelliklerine ilişkin bir inceleme. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 20(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steer, R. A., Ranieri, W. F., Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1993). Further evidence for the validity of the beck anxiety inventory with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 7, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, T., Hummelen, B., Himle, J. A., Walseth, L. T., Vogel, P. A., Launes, G., Haaland, V. Ø., & Haaland, Å. T. (2019). Early maladaptive schemas impact on long-term outcome in patients treated with group behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2003). Shame and guilt. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ulusoy, M., Sahin, N. H., & Erkmen, H. (1998). Turkish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory: Psychometric properties. Journal of cognitive psychotherapy, 12, 163. [Google Scholar]

- USGS Geologic Hazards Science Center and Collaborators. (2023). Tectonic setting. Available online: https://earthquake.usgs.gov/storymap/index-turkey2023.html (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2016). Mediation analysis: A practitioner’s guide. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulou, E., Karatzias, T., Hyland, P., Wallace, H., & Guzman, A. (2019). The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between childhood traumatic events and complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older adults (>64 years). Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(2), 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waclawski, E. (2012). How I use it: Survey monkey. Occupational Medicine, 62, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Wu, X., & Tian, Y. (2018). Mediating roles of gratitude and social support in the relation between survivor guilt and posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X., Gao, L., Shinfuku, N., Zhang, H., Zhao, C., & Shen, Y. (2000). Longitudinal study of earthquake-related PTSD in a randomly selected community sample in north China. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The ptsd checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). Available online: http://www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Wojcik, K. D., Cox, D. W., Kealy, D., Grau, P. P., Wetterneck, C. T., & Zumbo, B. (2022). Maladaptive schemas and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity: Investigating the mediating role of posttraumatic negative self-appraisals among patients in a partial hospitalization program. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 31, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y., Yu, H., Yao, Y., Peng, K., Wang, Y., & Chen, R. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder and the role of resilience, social support, anxiety and depression after the Jiuzhaigou earthquake: A structural equation model. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J., Klosko, J., & Weishaar, M. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

| Feature | Patient Group (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Marital status Married | 88 | 69 |

| Gender Female | 89 | 70 |

| Occupational Status: Employed | 106 | 83 |

| The presence of comorbid medical disorder, Yes | 29 | 23 |

| Psychiatric disorder history before the earthquake, Yes | 34 | 22 |

| Admission to psychiatric outpatient clinic after the earthquake Yes | 22 | 17 |

| Damage level of the survivors’ house | ||

| No damage | 58 | 37 |

| Low damaged | 42 | 27 |

| Moderately damaged | 9 | 6 |

| Highly damaged or destroyed | 17 | 11 |

| Place to stay in the first month after the earthquake | ||

| Former home | 24 | 19 |

| With relatives/friends | 66 | 52 |

| Relocated to another house | 14 | 11 |

| Tent/container | 7 | 6 |

| Facilities provided by the government/other support organization | 14 | 11 |

| Hospital | 2 | 2 |

| Survivors who have a relative or special others who lost their home, Yes | 70 | 56 |

| Survivors who had to relocate the city they lived before | 37 | 29 |

| Place of stay for the last 3 months | ||

| Former home | 91 | 72 |

| Relocate and living to another house | 18 | 14 |

| With relatives/another house (no private house) | 14 | 11 |

| Container/tent cities | 4 | 3 |

| Survivors who have a death relative or special others due to earthquake Yes | 38 | 30 |

| Total score of more than 17 on BDI | 45 | 35 |

| Total score of more than 16 on BAI | 59 | 47 |

| Total score of more than 48 on PCL-5 | 43 | 34 |

| Continuous Variables | ||

| Age (years) | 35.97 ± 9.04 | |

| Time duration between earthquake and the assessment procedure | 188.92 ± 13.46 | |

| Education years | 16.24 ± 3.03 | |

| Survivor Guilt Score | 4.20 ± 2.24 | |

| Beck Anxiety Scale (BAI) | 17.02 ± 13.49 | |

| PTSD Symptom Control Checklist (PCL-5) | 38.48 ± 20.41 | |

| PCL-5 Intrusion subdimensions score | 10.38 ± 5.41 | |

| Avoidance subdimensions score | 3.85 ± 2.19 | |

| Negative Alterations in Cognition and Mood Intrusion subdimensions score | 13.24 ± 7.43 | |

| Arousal and Reactivity subdimensions score | 13.00 ± 7.43 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PCL5 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Emotional Deprivation sch. | −0.046 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 3. Failure schema | 0.008 | 0.355 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 4. Pessimism | 0.463 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.366 ** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 5. Social Isolation/Insecurity | 0.174 | 0.519 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.547 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 6. Emotional İnhibition | 0.035 | 0.397 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.464 ** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 7. Admiration Seeking | 0.104 | 0.303 ** | 0.257 * | 0.399 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.272 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 8. Enmeshment/Dependency | 0.195 | 0.400 ** | 0.705 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.290 ** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 9. Insufficient Self-Control | 0.186 | 0.265 * | 0.176 | 0.339 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.315 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.167 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 10. Self-Sacrifice | 0.150 | 0.249 * | 0.199 | 0.265 * | 0.237 * | 0.263 * | 0.437 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.242 * | 1.000 | |||||

| 11. Abandonment | 0.142 | 0.531 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.454 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| 12. Self Punitiveness | 0.124 | 0.267 * | 0.164 | 0.469 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.243 * | 0.498 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.379 ** | 1.000 | |||

| 13. Defectiveness | 0.060 | 0.532 ** | 0.661 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.235 * | 0.587 ** | 0.176 | 0.100 | 0.533 ** | 0.195 | 1.000 | ||

| 14. Unrelenting Standards | 0.071 | 0.242 * | 0.132 | 0.455 ** | 0.391 ** | 0.255 * | 0.400 ** | 0.161 | 0.349 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.192 | 0.437 ** | 0.228 * | 1.000 | |

| 15. Vulnerability | 0.169 | 0.572 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.645 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.310 ** | 1.000 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Survivor Guilt | ||||||||||

| 2. PCL5 Intrusion Subscale | 0.481 ** | |||||||||

| 3. PCL5 Negative Alterations | 0.480 ** | 0.898 ** | ||||||||

| 4. PCL5 Avoidance | 0.587 ** | 0.796 ** | 0.805 ** | |||||||

| 5. PCL5 Arousal Alterations | 0.508 ** | 0.793 ** | 0.823 ** | 0.872 ** | ||||||

| 6. PCL5-Total Score | 0.561 ** | 0.914 ** | 0.910 ** | 0.950 ** | 0.943 ** | |||||

| 7. BAI-Total Score | 0.460 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.602 ** | 0.582 ** | 0.599 ** | ||||

| 8. BDI-Total Score | 0.513 ** | 0.541 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.466 ** | 0.552 ** | 0.573 ** | 0.669 ** | |||

| 9. Age | −0.195 * | −0.243 ** | −0.076 | −0.270 ** | −0.094 | −0.153 | −0.098 | −0.101 | ||

| 10. Time duration after earthquake | −0.129 | 0.047 | −0.010 | 0.103 | 0.029 | 00.30 | 0.078 | 0.002 | 0.039 | |

| 11. Education years | 0.022 | −0.141 | −0.027 | −0.151 | −0.121 | −0.105 | −0.160 | −0.075 | 0.065 | −0.024 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Survivor guilt | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Emotional Deprivation | 0.044 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 3. Failure | 0.298 * | 0.355 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 4. Pessimism | 0.328 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.366 ** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 5. Social Isolation/Insecurity | 0.233 * | 0.519 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.547 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 6. Emotional İnhibition | 0.213 | 0.397 ** | 0.459 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.464 ** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 7. Admiration Seeking | 0.221 | 0.303 ** | 0.257 * | 0.399 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.272 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 8. Enmeshment/Dependency | 0.337 ** | 0.400 ** | 0.705 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.508 ** | 0.290 ** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 9. Insufficient Self-Control | 0.060 | 0.265 * | 0.176 | 0.339 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.315 ** | 0.438 ** | 0.167 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 10. Self-Sacrifice | 0.118 | 0.249 * | 0.199 | 0.265 * | 0.237 * | 0.263 * | 0.437 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.242 * | 1.000 | |||||

| 11. Abandonment | 0.286 * | 0.531 ** | 0.557 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.585 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.536 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.454 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| 12. Self-Punitiveness | 0.064 | 0.267 * | 0.164 | 0.469 ** | 0.516 ** | 0.433 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.243 * | 0.498 ** | 0.551 ** | 0.379 ** | 1.000 | |||

| 13. Defectiveness | 0.244 * | 0.532 ** | 0.661 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.235 * | 0.587 ** | 0.176 | 0.100 | 0.533 ** | 0.195 | 1.000 | ||

| 14.Unrelenting standards | 0.033 | 0.242 * | 0.132 | 0.455 ** | 0.391 ** | 0.255 * | 0.400 ** | 0.161 | 0.349 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.192 | 0.437 ** | 0.228 * | 1.000 | |

| 15. Vulnerability | 0.103 | 0.572 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.561 ** | 0.645 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.574 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.461 ** | 0.310 ** | 1.000 |

| Survivor Guilt Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | MR | Sum of Ranks | ||

| Damage level of home | ||||

| Participants group whose house had low or no damage, | 99 | 56.98 | 5641.00 | |

| Participant group whose house had moderately or more severe damage | 26 | 85.92 | 2234.00 | |

| Statistics | U = 691.000, Z = −4.149, p = 0.000 | |||

| Place of stay for the last 3 months | ||||

| The participants who are continuing to stay at former home before earthquake | 91 | 56.38 | 5131.00 | |

| Other places | 34 | 80.71 | 2744.00 | |

| Statistics | U = 945.000, Z = −3.823, p = 0.000 | |||

| Survivors who have at least one death of a relative or special others due to earthquake | ||||

| Who have a death of a relative or special others | 37 | 76.20 | 2819.50 | |

| Who have no death of a relative or special others due to earthquake | 88 | 57.45 | 5055.50 | |

| Statistics | U = 1139.500, Z = −3.024, p = 0.002 | |||

| Survivors whose home was destroyed due to earthquake | ||||

| Participants whose home was destroyed due to earthquake | 10 | 93.35 | 933.50 | |

| Other participants | 114 | 59.79 | 6816.50 | |

| Statistics | U = 261.500, Z = −3.252, p = 0.001 | |||

| Survivors whose relatives/friends’ home was destroyed in the earthquake | ||||

| Participants whose relatives/friends’ home was destroyed due to earthquake | 69 | 71.36 | 4924.00 | |

| Other participants | 56 | 52.70 | 2951.00 | |

| Statistics | U = 1355.000, Z = −3.279, p = 0.001 | |||

| Survivors who had to relocate from the city they lived before | ||||

| Participants who had to relocate from their city | 36 | 76.38 | 2749.50 | |

| Others | 89 | 57.59 | 5125.50 | |

| Statistic | U = 1120.500, Z = −3.005, p = 0.003 | |||

| Place to stay in the first month after the earthquake | ||||

| The survivors who stayed to continue at former home and who stayed in their relatives’ or friends’ home | 89 | 59.49 | 5294.50 | |

| The survivors who had to relocate to another house and who stayed in facilities provided by the government/other support organizations, containers, tents, or hospitals | 34 | 68.57 | 2331.50 | |

| Statistics | U = 1289.500, Z = −1.458, p = 0.145 | |||

| Existence of anxiety disorder | ||||

| BAI score was lower than cut off level (no anxiety disorder) | 66 | 51.48 | 3398.00 | |

| BAI score was higher than cut off level (existence of anxiety disorder) | 59 | 75.88 | 4477.00 | |

| Statistics | U = 1187.000, Z = −4.302, p = 0.000 | |||

| Existence of Depression | ||||

| BDI score was lower than cut off level (no depression) | 80 | 53.66 | 4292.50 | |

| BDI score was higher than cut off level (existence of depression) | 45 | 79.61 | 3582.50 | |

| Statistics | U = 1052.500, Z = −4.400, p = 0.000 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 88 | 64.76 | 5699.00 | |

| Male | 37 | 58.81 | 2176.00 | |

| Statistics | U = 1473.000, Z = −0.959, p = 0.337 | |||

| Psychiatric disorder history before the earthquake | ||||

| Yes | 34 | 64.26 | 2185.00 | |

| No | 91 | 62.53 | 5690.00 | |

| Statistics | U = 1504.00, Z = −0.273, p = 0.785 | |||

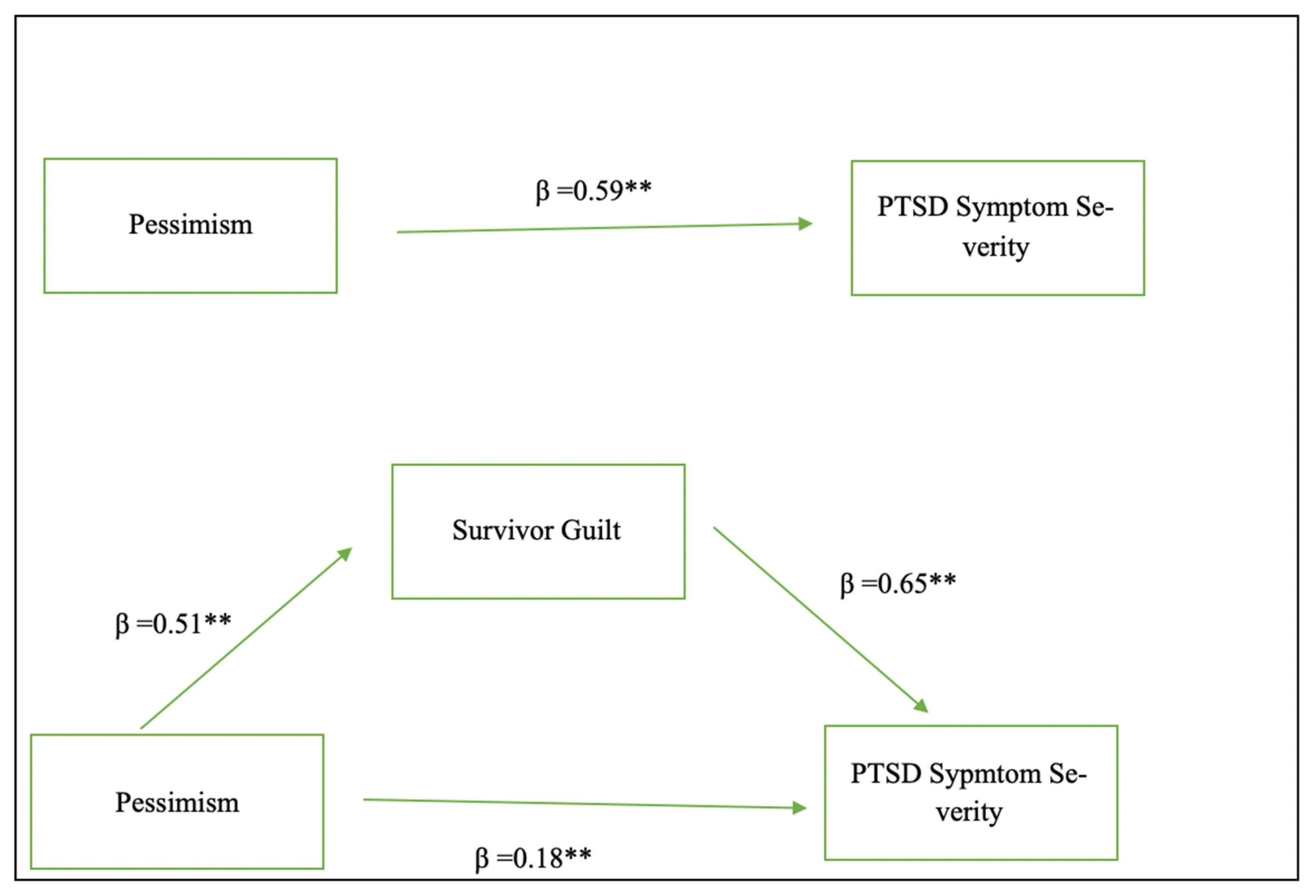

| Effect | Pathway | Standardized Beta | Standard Error | Confidence Interval (95%) | F Value, t Value, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Pessimism → PTSD | 0.59 | 0.25 | 1.53–2.52 | F(1,123) = 66.01, t = 8.12, p = 0.00 |

| İndirect | Pessimism → Survivor guilt → PTSD | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.10–0.26 | F(2,122) = 49.06 p = 0.00 |

| Direct | Pessimism → PTSD | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.87–1.94 | t = 5.24, p = 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kızılpınar, S.Ç.; Kılıç-Demir, B. Survivor Guilt as a Mediator Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Pessimism Schema After Türkiye-Syria Earthquake. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091199

Kızılpınar SÇ, Kılıç-Demir B. Survivor Guilt as a Mediator Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Pessimism Schema After Türkiye-Syria Earthquake. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091199

Chicago/Turabian StyleKızılpınar, Selma Çilem, and Barış Kılıç-Demir. 2025. "Survivor Guilt as a Mediator Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Pessimism Schema After Türkiye-Syria Earthquake" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091199

APA StyleKızılpınar, S. Ç., & Kılıç-Demir, B. (2025). Survivor Guilt as a Mediator Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Pessimism Schema After Türkiye-Syria Earthquake. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1199. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091199