Longitudinal Links Between Perceived Family Support, Self-Efficacy, and Growth Mindset of Intelligence Among Chinese Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived Family Support and the Growth Mindset of Intelligence

1.2. Role of Self-Efficacy in Linking Perceived Family Support to Growth Mindset

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Perceived Family Support

2.3.2. Self-Efficacy

2.3.3. Growth Mindset

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among the Main Variables

3.2. Cross-Lagged Model of the Link Between Perceived Family Support and Growth Mindset

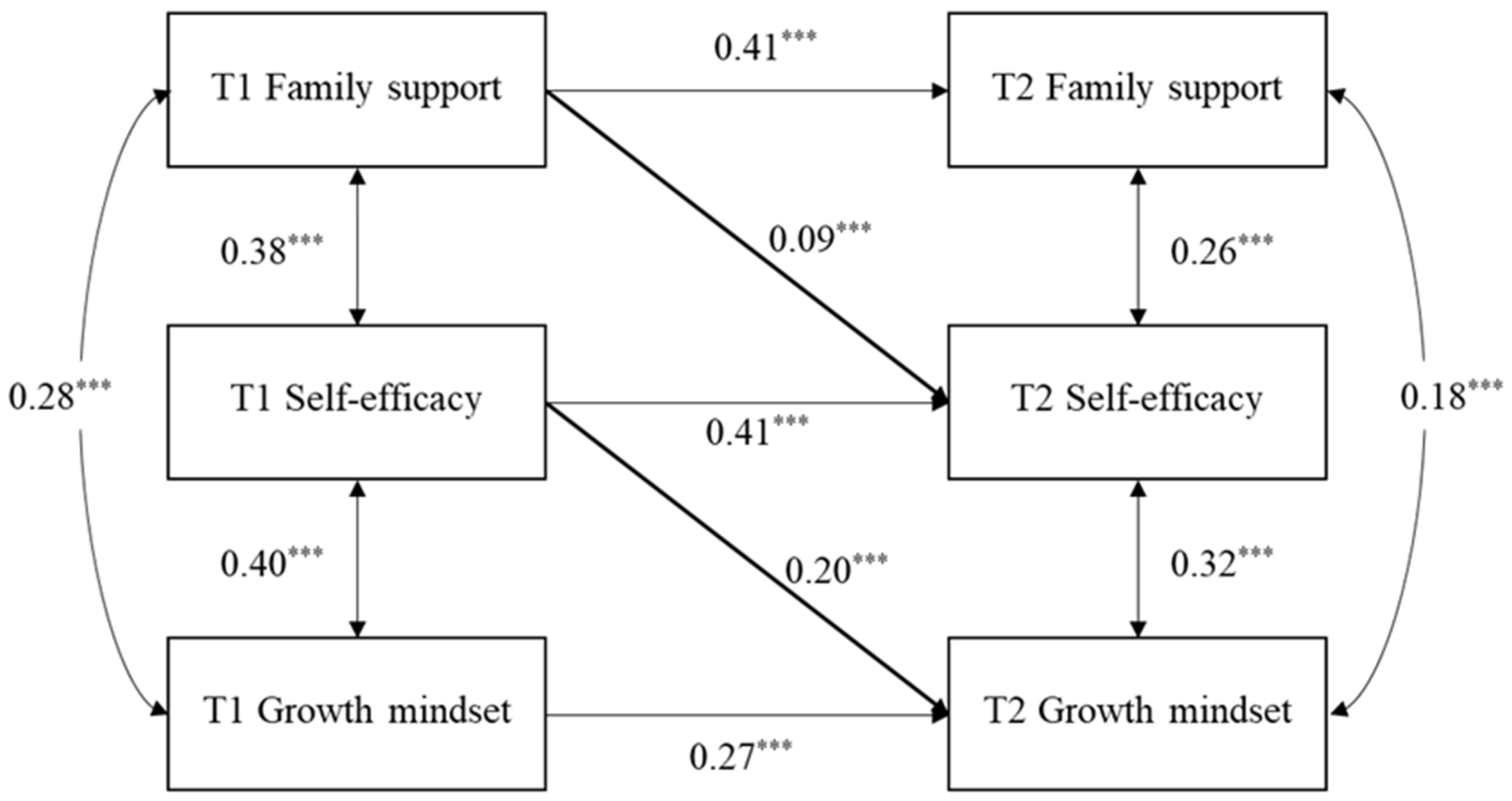

3.3. Mediation Model for T2 Growth Mindset

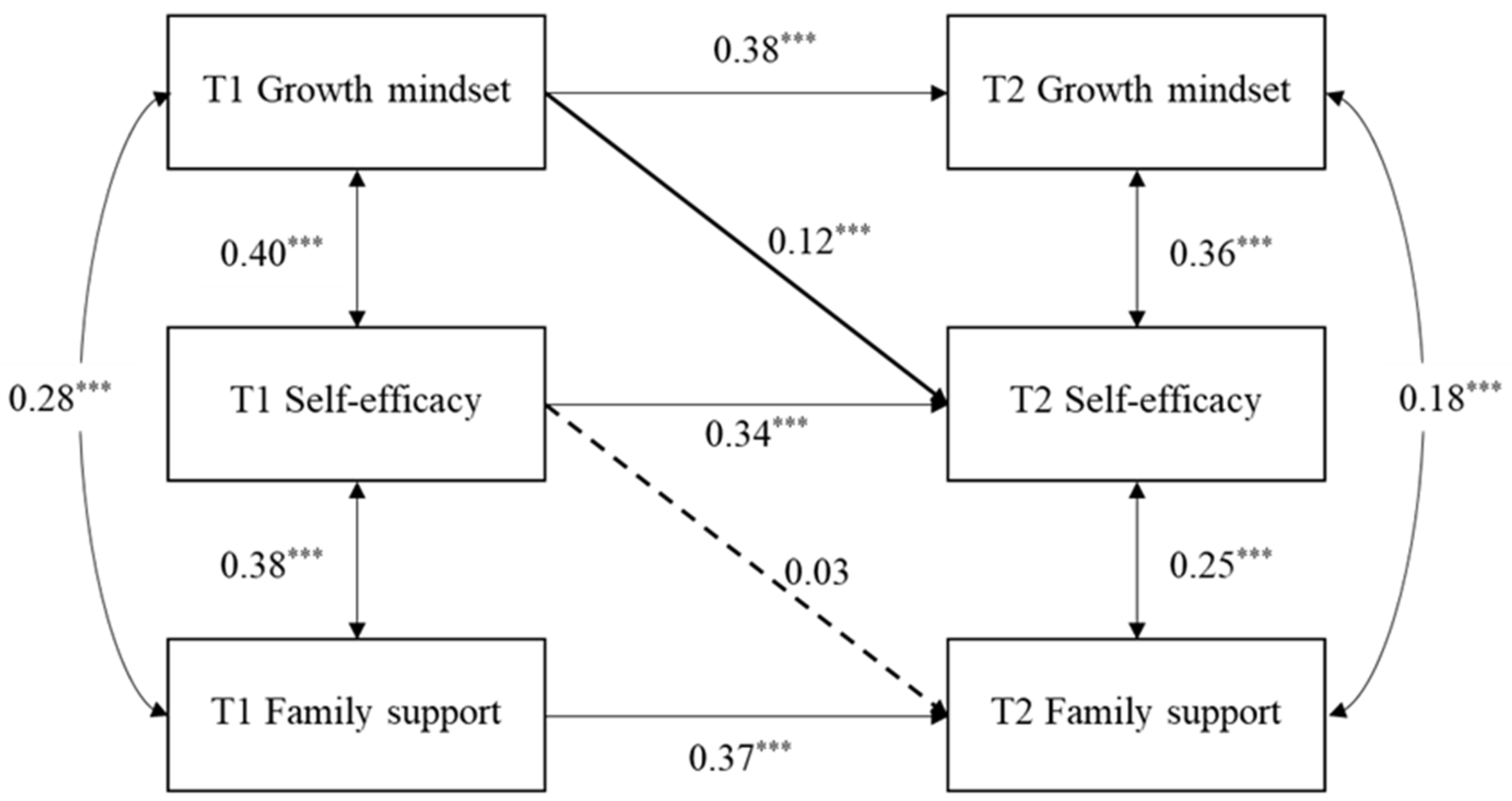

3.4. Mediation Model for T2 Perceived Family Support

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items

- The four items that measure Perceived Family Support for children:

- 1.

- My family really tries to help me.

- 2.

- I get the emotional help and support I need from my family.

- 3.

- I can talk about my problems with my family.

- 4.

- My family is willing to help me make decisions.

- The ten items measure Self-efficacy for children:

- 1.

- I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough.

- 2.

- if someone opposes me, I can find means and ways to get what I want.

- 3.

- it is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals.

- 4.

- I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events.

- 5.

- Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations.

- 6.

- I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort.

- 7.

- I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities.

- 8.

- When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions.

- 9.

- If I am in trouble, I can usually think of something to do.

- 10.

- No matter what comes my way, I am usually able to handle it.

- The three items that measure Growth Mindset for children:

- 1.

- You have a certain amount of intelligence, and you can’t really do much to change it.

- 2.

- Your intelligence is something about you that you can’t change very much.

- 3.

- You can learn new things, but you can’t really change your basic intelligence.

References

- Altikulaç, S., Janssen, T. W. P., Yu, J., Nieuwenhuis, S., & Van Atteveldt, N. M. (2024). Mindset profiles of secondary school students: Associations with academic achievement, motivation and school burnout symptoms. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 738–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asici, E., Katmer, A. N., & Agca, M. A. (2024). Linking perceived family and peer support to hope in Syrian refugee adolescents: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 42, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1(4), 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67(3), 1206–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, M. M., Wu, J., Xiong, Y., Oh, D. D., Cimpian, A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2022). Parents’ responses to children’s math performance in early elementary school: Links with parents’ math beliefs and children’s math adjustment. Child Development, 93(6), e639–e655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begen, F. M., & Turner-Cobb, J. M. (2015). Benefits of belonging: Experimental manipulation of social inclusion to enhance psychological and physiological health parameters. Psychol Health, 30(5), 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R. H. (2024). Home environment. In W. Troop-Gordon, & E. W. Neblett (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (2nd ed., pp. 201–211). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments in nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. L. W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2010). Parent–child attachment and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A review of empirical findings and future directions. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2004). General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Zhang, Y., & Tang, Y. (2024). The relationship between school climate and growth mindset of junior middle school students: A mediating model of perceived social support and positive personality. Current Psychology, 43(5), 4142–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkelmann, I., & Buff, A. (2016). Children’s and parents’ perceptions of parental support and their effects on children’s achievement motivation and achievement in mathematics. A longitudinal predictive mediation model. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). The journey to children’s mindsets—And beyond. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C.-Y., & Hong, Y.-Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M. W., Long, L. J., & Phillips, C. A. (2020). Hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analytic review of the protective effects of positive expectancies. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(3), 329–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, C., & Jose, P. E. (2024). Relationships between family connectedness and stress-triggering problems among adolescents: Potential mediating role of coping strategies. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 52(2), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W. S., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 65(1), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecht, C. A., Yeager, D. S., Dweck, C. S., & Murphy, M. C. (2021). Beliefs, affordances, and adolescent development: Lessons from a decade of growth mindset interventions. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 61, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerde, J. A., & Hemphill, S. A. (2018). Examination of associations between informal help-seeking behavior, social support, and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 47, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T., & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. (2016). Achievement goals and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 19, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huver, R. M. E., Otten, R., de Vries, H., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2010). Personality and parenting style in parents of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 33(3), 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M. H. (2023). A bioecological perspective on mindset. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 73, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & Wang, F. M. (2025). The rich get richer: Socioeconomic advantage amplifies the role of growth mindsets in learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleppang, A. L., Steigen, A. M., & Finbråten, H. S. (2023). Explaining variance in self-efficacy among adolescents: The association between mastery experiences, social support, and self-efficacy. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarraju, M., & Nadler, D. (2013). Self-efficacy and academic achievement: Why do implicit beliefs, goals, and effort regulation matter? Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, Y., Nelemans, S. A., Bosmans, G., van den Noortgate, W., Van Leeuwen, K., & Goossens, L. (2023). Perceived parental support and psychological control, DNA methylation, and loneliness: Longitudinal associations across early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52, 1995–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X., Ma, C., & Radin, R. (2019). Parental autonomy support and psychological well-being in Tibetan and Han emerging adults: A serial multiple mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. J., & Mendoza, N. B. (2025). Does parental support amplify growth mindset predictions for student achievement and persistence? Cross-cultural findings from 76 countries/regions. Social Psychology of Education, 28(1), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2003). U.S and Chinese cultural beliefs about learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2005). Mind or virtue: Western and Chinese beliefs about learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(4), 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Sang, B., Liu, J., Gong, S., & Ding, X. (2019). Parental support and homework emotions in Chinese children: Mediating roles of homework self-efficacy and emotion regulation strategies. Educational Psychology, 39(5), 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B., Zhou, H., Liu, C., Guo, X., Liu, J., Jiang, K., Liu, Z., & Luo, L. (2018). The relationship between parental involvement and children’s self-efficacy profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(11), 3730–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, E. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2010). Ability mindsets influence the quality of mothers’ involvement in children’s learning: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, F. F.-Y., & Wei, J. (2020). Delving into the minds of Chinese parents: What beliefs motivate their learning-related practices? Child Development Perspectives, 14(1), 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcel, T. L., & Bixby, M. S. (2016). The ties that bind: Social capital, families, and children’s well-being. Child Development Perspectives, 10(2), 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D., Tsukayama, E., Yu, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2020). The development of grit and growth mindset during adolescence. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 198, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluektova, O., Kappas, A., & Smith, C. A. (2023). Using Bandura’s self-efficacy theory to explain individual differences in the appraisal of problem-focused coping potential. Emotion Review, 15(4), 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B., Grüning, D. J., & Lechner, C. M. (2024). Measuring growth mindset: Validation of a three-item and a single-item scale in adolescents and adults. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 40(1), 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, M., Hanselman, P., Solli, I. F., Dweck, C. S., Ludvigsen, S., Bettinger, E., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Walton, G., Duckworth, A., & Yeager, D. S. (2021). How can we inspire nations of learners? An investigation of growth mindset and challenge-seeking in two countries. American Psychologist, 76(5), 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, S. E. (1988). Social support: Implications for counselling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 11, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., Mueller, J., & Greenglass, E. (1999). Assessment of perceived general self-efficacy on the internet: Data collection in cyberspace. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 12(2), 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Nancekivell, S., Gelman, S. A., & Shah, P. (2021). Growth mindset and academic outcomes: A comparison of US and Chinese students. NPJ Science of Learning, 6(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 751–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Egmond, M. C., Kühnen, U., & Li, J. (2013). Mind and virtue: The meaning of learning, a matter of culture? Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 2(3), 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, A. C., Patall, E. A., Fong, C. J., Corrigan, A. S., & Pine, L. (2016). Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 605–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestad, L., & Bru, E. (2024). Teachers’ support for growth mindset and its links with students’ growth mindset, academic engagement, and achievements in lower secondary school. Social Psychology of Education, 27(4), 1431–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). Seed and soil: Psychological affordances in contexts help to explain where wise interventions succeed or fail. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(3), 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Ng, F. F.-Y. (2012). Chinese students’ implicit theories of intelligence and school performance: Implications for their approach to schoolwork. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(8), 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Wang, Y. (2024). The impact of perceived social support on e-learning engagement among college students: Serial mediation of growth mindset and subjective well-being. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(4), 4163–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Sun, X. (2025). Growth mindset in Chinese culture: A meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 28(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., Carroll, J. M., Buontempo, J., Cimpian, A., Woody, S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Murray, J., Mhatre, P., Kersting, N., Hulleman, C., Kudym, M., Murphy, M., Duckworth, A. L., Walton, G. M., & Dweck, C. S. (2022). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth-mindset intervention does and doesn’t work. Psychological Science, 33(1), 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 267–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, L., Brouwer, J., Jansen, E., Crayen, C., & Hannover, B. (2018). Academic self-efficacy, growth mindsets, and university students’ integration in academic and social support networks. Learning and Individual Differences, 62, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Jiang, Y., Ming, H., Ren, Y., Wang, L., & Huang, S. (2020). Family socio-economic status and children’s academic achievement: The different roles of parental academic involvement and subjective social mobility. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F., & Yang, R. (2025). Parental expectations and adolescents’ happiness: The role of self-efficacy and connectedness. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T., Park, D., Ungar, L. H., Tsukayama, E., Luo, L., & Duckworth, A. L. (2022). The development of grit and growth mindset in Chinese children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 221, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived family support (T1) | 5.05 | 1.44 | — | ||||||

| 2. Self-efficacy (T1) | 2.64 | 0.56 | 0.38 *** | — | |||||

| 3. Growth mindset (T1) | 4.04 | 1.16 | 0.28 *** | 0.41 *** | — | ||||

| 4. Perceived family support (T2) | 5.12 | 1.49 | 0.42 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.20 *** | — | |||

| 5. Self-efficacy (T2) | 2.68 | 0.61 | 0.28 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.39 *** | — | ||

| 6. Growth mindset (T2) | 3.87 | 1.21 | 0.23 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.53 *** | — | |

| 7. Gender | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | — |

| 8. Age (T1) | 10.76 | 0.93 | −0.01 | −0.004 | −0.08 *** | −0.01 | −0.06 ** | −0.08 *** | −0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, W.; Zhang, F. Longitudinal Links Between Perceived Family Support, Self-Efficacy, and Growth Mindset of Intelligence Among Chinese Children. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091182

Peng W, Zhang F. Longitudinal Links Between Perceived Family Support, Self-Efficacy, and Growth Mindset of Intelligence Among Chinese Children. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091182

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Wei, and Feng Zhang. 2025. "Longitudinal Links Between Perceived Family Support, Self-Efficacy, and Growth Mindset of Intelligence Among Chinese Children" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091182

APA StylePeng, W., & Zhang, F. (2025). Longitudinal Links Between Perceived Family Support, Self-Efficacy, and Growth Mindset of Intelligence Among Chinese Children. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1182. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091182