Violence Against Nurses: Personal and Institutional Coping Strategies—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Information and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Original Selection of Studies

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment Methodology

2.6. Analysis and Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Included Studies

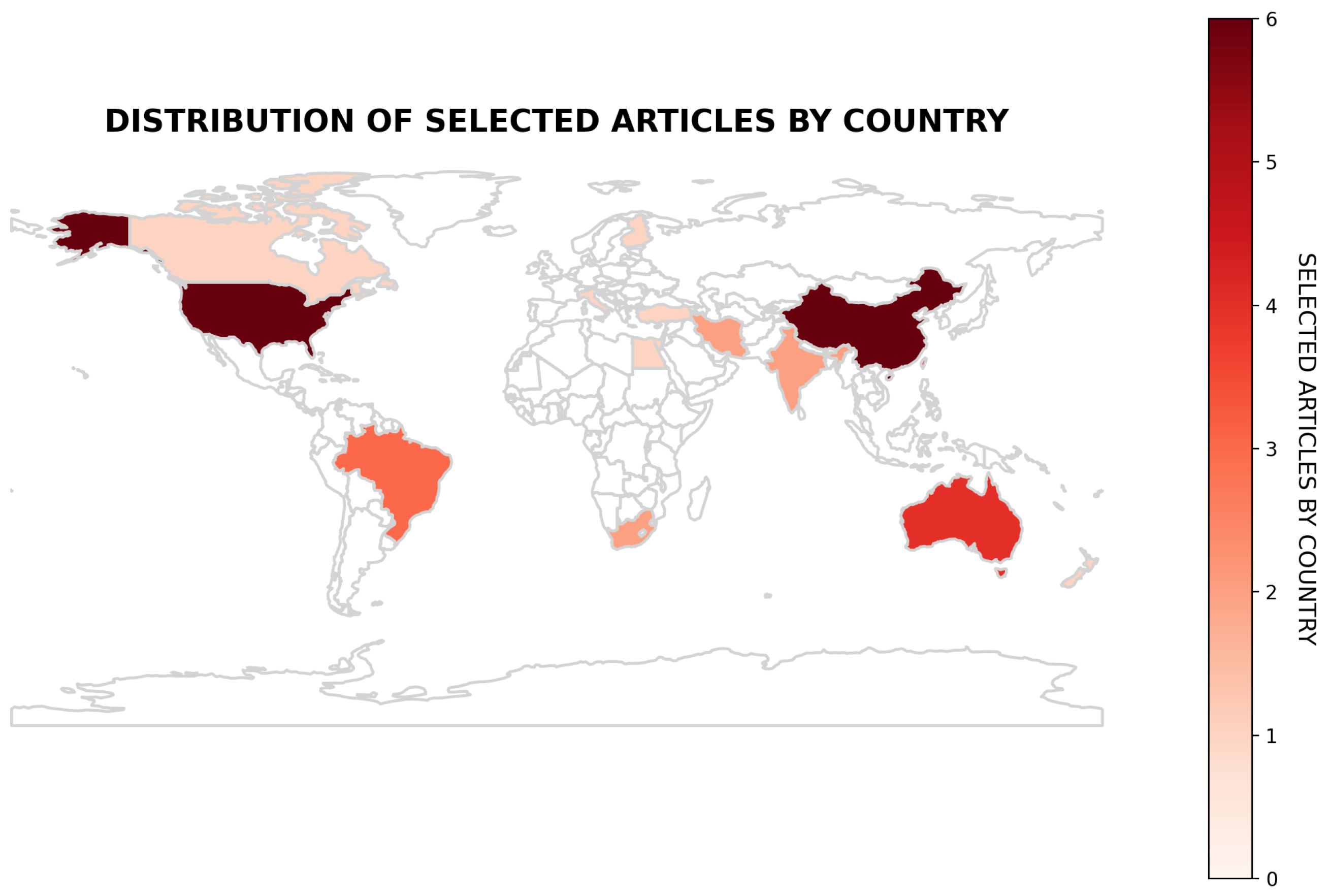

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Assessment of Methodological Quality

3.4. Action Strategies Perceived by Nurses

3.4.1. Before the Event of Workplace Violence

3.4.2. During the Event of Workplace Violence

3.4.3. After the Event of Violence in the Workplace

3.4.4. Organizational and Institutional Strategies Against Workplace Violence

3.4.5. Personal and Peer Support Strategies

3.5. Applied Implementation Strategies

3.5.1. Simulation and Training

3.5.2. Technological Intervention Tools

3.5.3. Structured Models of Prevention and Response

3.6. Practical Implications and Recommendations

4. Discussion

4.1. Action Strategies as Perceived by Nurses

4.2. Practical Implementation Strategy

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEBM | Center for Evidence-Based Management |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Agu, A., Azuogu, B., Una, A., Ituma, B., Eze, I., Onwe, F., Oka, O., Igwe-Okomiso, D., Agbo, U., Ewah, R., & Uneke, J. (2023). Management staff’s perspectives on intervention strategies for workplace violence prevention in a tertiary health facility in Nigeria: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11(1), 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadi, M. (2021). Workplace violence in nursing: A concept analysis. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakes-Denman, L., Mansfield, Y., & Meehan, T. (2021). Supporting mental health staff following exposure to occupational violence—Staff perceptions of ‘peer’ support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekelepi, N., & Martin, P. (2022). Experience of violence, coping and support for nurses working in acute psychiatric wards. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blando, J. D., O’Hagan, E., Casteel, C., Nocera, M., & Peek-Asa, C. (2013). Impact of hospital security programmes and workplace aggression on nurses’ perceptions of safety. Journal of Nursing Management, 21(3), 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, M., Trindade, L., Cezar-Vaz, M., & Monteiro, M. (2021). Workplace violence: Legislation, public policies and the possibility of advances for health workers. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 74(1), 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkoski, V., Farshait, N., Yoon, J., Clancy, P. V., Fernandes, K., Howell, M. R., Solomon, S., Orrico, M. E., & Collins, B. E. (2019). Violence prevention: Technology-enabled therapeutic intervention. Nursing Leadership, 32(SP), 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabilan, C. J., Eley, R., Snoswell, C. L., & Johnston, A. N. B. (2022). What can we do about occupational violence in emergency departments? A survey of emergency staff. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(6), 1386–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Wu, S., Wang, H., Zhao, X., Ying, Y., Zhang, Y., & Tang, Z. (2023). The effectiveness of a workplace violence prevention strategy based on situational prevention theory for nurses in managing violent situations: A quasi-experximental study. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, K., Araujo, P., Santos, F., Oliveira, P., Silva, J., Santos, K., Viana, A., & Fortuna, C. (2023). Violence in the nursing workplace in the context of primary health care: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(17), 6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEBM. (2020). Critical appraisal questionnaires. Center for Evidence-Based Management. Available online: https://cebma.org/resources/tools/critical-appraisal-questionnaires/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Chang, Y. C., Hsu, M. C., & Ouyang, W. C. (2022). Effects of integrated workplace violence management intervention on occupational coping self-efficacy, goal commitment, attitudes, and confidence in emergency department nurses: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, D., & Henry, M. (2017). Workplace violence and perceptions of safety among emergency department staff members: Experiences, expectations, tolerance, reporting, and recommendations. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 24(2), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashzadeh, A., Rahmani, A., Hassankhani, H., Boyle, M., Mohammadi, E., & Campbell, S. (2019). Iranian pre-hospital emergency care nurses’ strategies to manage workplace violence: A descriptive qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(6), 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dafny, H. A., Beccaria, G., & Muller, A. (2022). Australian nurses’ perceptions about workplace violence management, strategies and support services. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(6), 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, K., Ravishankar, V., Mehta, N., Ahluwalia, T., Blanchard, J., Smith, J., & Douglass, K. (2020). A qualitative study of workplace violence among healthcare providers in emergency departments in India. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(33), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, M., Schoenfisch, A., Wadsworth, B., & Foresman-Capuzzi, J. (2019). impact of behavior management training on nurses’ confidence in managing patient aggression. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(2), 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ettorre, G., Pellicani, V., Mazzotta, M., & Vullo, A. (2018). Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in emergency departments. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 89(4), 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmerling, S. A., McGarvey, J., & Burdette, K. (2024). Evaluating a workplace violence management program and nurses’ confidence in coping with patient aggression. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 54(3), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S., An, W., Zeng, L., Liu, J., Tang, S., Chen, J., & Huang, H. (2022). Rethinking “zero tolerance”: A moderated mediation model of mental resilience and coping strategies in workplace violence and nurses’ mental health. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 54(4), 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórido, H. G., Duarte, S., Floresta, W., Marins, A., Broca, P., & Moraes, J. (2020). Nurse’s management of workplace violence situations in the family health strategy. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem, 29(1), 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gab Allah, A. R., Elshrief, H. A., & Ageiz, M. H. (2020). Developing Strategy: A guide for nurse managers to manage nursing staff’s work-related problems. Asian Nursing Research (Korean Society of Nursing Science), 14(3), 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacki-Smith, J., Juarez, A., Boyett, L., Homeyer, C., Robinson, L., & MacLean, S. (2009). Violence against nurses working in US emergency departments. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(7–8), 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C. Y., Chen, L. C., Lin, C. C., Goopy, S., & Lee, H. L. (2021). How emergency nurses develop resilience in the context of workplace violence: A grounded theory study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 53(5), 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N., Jeong, S., & Smith, T. (2021). Negative workplace behavior and coping strategies among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 23(1), 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, S. (2022). Changing attitudes about workplace violence: Improving safety in an acute care environment. Journal of Healthcare Risk Management, 42(2), 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F., Chen, Y.-M., Chen, S.-L., & Wang, H.-H. (2023). Understanding the workplace-violence-related perceptions and coping strategies of nurses in emergency rooms. The Journal of Nursing Research, 31(6), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F., Huang, I.-C., Liu, Y., Chen, W.-L., Lee, Y.-W., & Hsu, H.-T. (2020). The effects of biofeedback training and smartphone-delivered biofeedback training on resilience, occupational stress, and depressive symptoms among abused psychiatric nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikpae, E., & Buowari, D. (2023). Characteristics of workplace violence on doctors and nurses at the accident and emergency department in a southern state of Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal, 64(3), 398–407. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, S., & Brunero, S. (2018). The effect of a workplace violence training program for generalist nurses in the acute hospital setting: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Education Today, 68, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L., Guo, N., Qu, J., Ruan, C., & Wang, L. (2024). Effect, feasibility, and acceptability of a Comprehensive Active Resilience Education (CARE) program in emergency nurses exposed to workplace violence: A quasi-experimental, mixed-methods study. Nurse Education Today, 139, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z. Y., Idris, D. R., Abdullah, H. M. A. L., & Omar, H. R. (2023). Violence toward staff in the inpatient psychiatric setting: Nurses’ perspectives: A qualitative study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 46, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J., Gan, Y., Jiang, H., Li, L., Dwyer, R., Lu, K., Yan, S., Sampson, O., Xu, H., Wang, C., Zhu, Y., Chang, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, T., Chen, Y., Song, F., & Lu, Z. (2019). Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 76(12), 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, L., Kaczorowski, K., White, M., Dickens, G., & McDermid, F. (2024). Medical and surgical nurses’ experiences of modifying and implementing contextually suitable Safewards interventions into medical and surgical hospital wards. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 80(11), 4639–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I., Moloney, W., Jacobs, S., & Anderson, N. (2024). Support mechanisms that enable emergency nurses to cope with aggression and violence: Perspectives from New Zealand nurses. Australas Emerg Care, 27(2), 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkola, R., Huhtala, H., & Paavilainen, E. (2019). Development of a coping model for work-related fear among staff working in the emergency department in Finland—Study for nursing and medical staff. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(3), 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, J., Huang, H., Hung, S., Chang, C., Hsu, Y., Tzeng, Y., Huang, H., & Hsu, T. (2019). Using simulation training to promote nurses’ effective handling of workplace violence: A quasi-experimental study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, B., Nikathil, S., Gocentas, R., Symons, E., O’Reilly, G., & Olaussen, A. (2018). Security interventions for workplace violence in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia: EMA, 30(6), 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, G., & Kowal, C. (2024). Patient and visitor verbal aggression toward frontline health-care workers: A qualitative study of experience and potential solutions. Journal of Aggression, 16(2), 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikathil, S., Olaussen, A., Gocentas, R. A., Symons, E., & Mitra, B. (2017). Review article: Workplace violence in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta analysis. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 29(3), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkadimeng, M., Engelbrecht, A., & Rajan, S. (2024). Workplace violence in three public sector emergency departments, Gauteng, South Africa: A cross-sectional survey. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14(4), 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztaş, İ., Yava, A., & Koyuncu, A. (2023). Exposure of emergency nurses to workplace violence and their coping strategies: A cross-sectional design. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 49(3), 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poore, J., Chassity, L., McKibban, L., Harbert, Z., & Schroedle, K. (2024). Using simulated patients to teach de-escalation during registered nurses’ onboarding. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 94(1), 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. (2020). PRISMA 2020 checklist. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-checklist (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Quigley, E., Schwoebel, A., Ruggiero, J., Inacker, P., McEvoy, T., & Hollister, S. (2021). Addressing workplace violence and aggression in health care settings: One unit’s journey. Nurse Leader, 19(1), 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, F., Jahangiri, M., Bagherifard, F., Banaee, S., & Farhadi, P. (2020). Strategies for controlling violence against health care workers: Application of fuzzy analytical hierarchy process and fuzzy additive ratio assessment. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(4), 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, D. (2023). Violence against healthcare workers. Cuadernos Médico Sociales, 63(2), 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, L., Sak-Dankosky, N., & Czarkowska-Pączek, B. (2020). Bullying in nursing evaluated by the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(6), 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sé, A., Machado, W., & Gonçalves, R. (2021). Preventive strategies against violence at work from the per-spective of pre-hospital care nurses. Revista de Pesquisa Cuidado é Fundamental Online, 13(1), 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Ranjan, P., Agrawal, R., Kaur, T., Upadhyay, A. D., Nayer, J., Chakrawarty, B., Sarkar, S., Joshi, M., Kaur, T. P., Mohan, A., Chakrawarty, A., & Kumar, K. R. (2023). Workplace violence in healthcare settings: A cross-sectional survey among healthcare workers of North India. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 27(4), 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. R., Palazzo, S. J., Grubb, P. L., & Gillespie, G. L. (2020). Standing up against workplace bullying behavior: Recommendations from newly licensed nurses. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 10(7), 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, A. R., Harris, R., Scott, S. D., & Vogelsmeier, A. (2020). An evaluation of nurses’ perception and confidence after implementing a workplace aggression and violence prevention training program. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(4), 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2023). Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Van Haastrecht, M., Sarhan, I., Yigit Ozkan, B., Brinkhuis, M., & Spruit, M. (2021). SYMBALS: A systematic review methodology blending active learning and snowballing. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 6(1), 685591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). New WHO/ILO guide URGES greater safeguards to protect health workers. Available online: https://dev-cms.who.int/news/item/21-02-2022-new-who-ilo-guide-urges-greater-safeguards-to-protect-health-workers (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Xiao, Y., Chen, T. T., Zhu, S. Y., Zong, L., Du, N., Li, C. Y., Cheng, H. F., Zhou, Q., Luo, L. S., & Jia, J. (2022). Workplace violence against Chinese health professionals 2013-2021: A study of national criminal judgment documents. Frontiers in Public Health, 19(10), 1030035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J., Xiao, A., Wang, C., Xia, Z., Yu, L., Li, S., Lin, J., Liao, Y., Xu, Y., & Zhang, Y. L. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of a CRSCE-based de-escalation training program among psychiatric nurses: A study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Services Research, 20(642), 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, W., Siddiqui, E., Ejaz, K., Shehzad, M., Khan, U., Jamali, S., & Razzak, J. (2013). Health care personnel and workplace violence in the emergency departments of a volatile metropolis: Results from Karachi, Pakistan. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 45(5), 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Cai, J., Qin, Z., Wang, H., & Hu, X. (2023). Evaluating the impact of an information-based education and training platform on the incidence, severity, and coping resources status of workplace violence among nurses: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Nursing, 22(446), 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S., Liu, H., Ma, H., Jiao, M., Li, Y., Hao, Y., Sun, Y., Gao, L., Hong, S., Kang, Z., Wu, Q., & Qiao, H. (2015). Coping with Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: Social Support and Strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(11), 14429–14444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Workplace Violence AND | Coping Strategies AND | Nursing |

|---|---|---|

| Mobbing | Coping | Nurses |

| Bullying | Strategies | Health workers |

| Patient and visitor violence | ||

| Violence against healthcare workers |

| Authors, Country, Year | Aim | Methodology | Interventions | Methodological Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse-perceived strategies | ||||

| Fan S, et al., 2021. China | To assess the impact of violence on nurses’ mental health and its related variation in resilience and coping strategies | Cross-sectional study | Questionnaire | Good quality |

| Hsieh H, Chen Y, Chen S, Wang H., 2023 Taiwan | Understanding the perceptions of nurses who have been victims of violence in work settings and their coping strategies | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Han C, Chen L, Lin C, Goopy S, Lee H., 2024 Taiwan | Understanding how emergency nurses develop resilience in the context of workplace violence | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Dadashzadeh A, Rahmani A, Hassankhani H., 2019 Ira | To explore the experiences of Iranian nurses working in pre-hospital emergencies and strategies for coping with violence | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Rajabi F, Jahangiri M, Bagherifard F, Banaee S., 2000 Iran, 2020. | Addressing the problem of occupational violence in health care settings | Qualitative study | Interviews with guiding dialogue questions | Good quality |

| Gab Allah A, Elshrief H, Ageiz M., 2020 Egypt | Evaluating nursing work-related problems as perceived by managers and developing strategies for decision making | Cross-sectional study | Questionnaire, Delphi technique, and interview | Satisfactory quality |

| Singh A, Ranjan P, Agrawal R, Kaur T, Upadhyay A., 2023. India. | Assessing the problem of violence against healthcare workers in healthcare settings | Cross-sectional study | Questionnaire | Good quality |

| Davey K, et al., 2020 India | To gain a better understanding of issues surrounding violence against healthcare providers in Indian EDs | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Lim, Z., 2023 Brunei Darussalam | Identify and explore the impact of violence on mental health nurses and discuss nurses’ coping mechanisms | Qualitative study | Electronic interview | Good quality |

| Öztaş İ, Yava A, Koyuncu, A., 2023 Turkey. | Determine emergency nurses’ exposure to workplace violence by patients and their relatives and the nurses’ use of coping behaviors/methods | Cross-sectional study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Smith C, Palazzo S, Grubb P, Gillespie G., 2020 United State. | To explore strategies suggested by new graduate nurses to prevent and intervene during incidents of violence in work settings | Qualitative study | Interviews with guiding dialogue questions | Good quality |

| Myers G, Kowal C., 2023 United States | Explore encounters with verbal aggression and solutions offered by nurses | Qualitative study | Surveys and interviews | Good quality |

| Bekelepi N, Martin P., 2022 South Africa | To explore and describe the experiences of nurse victims of violence, as well as strategies and the support received | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Agu A, Azuogu B, Una A, Ituma B, Eze I, Onwe F, Oka O., 2023 Africa | To uncover managerial perspectives on intervention strategies for violence in the workplace and tertiary health prevention | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Bakes L, Mansfield Y, Meechan T., 2021 Australia | Understand staff perceptions of peer support after incidents of violence | Qualitative study | Structured interviews | Satisfactory quality |

| Dafny H, Beccaria G, Muller A., 2022 Australia | To determine nurses’ perceptions of management, strategies, and support services for violence in work settings | Qualitative study | Surveys with closed and open-ended questions | Good quality |

| Cabilan C, 2022 Australia | To explore and collate solutions for occupational violence from emergency department (ED) staff | Qualitative study | Electronic survey | Good quality |

| Martins, Moloney, Jacobs, y Anderson, 2023 New Zealand | Provide evidence to support nurses affected by workplace aggression and violence | Mixed methods | Lickert-type survey and semi-structured interview | Good quality |

| Sé A, Machado W, Gonçalves R., 2021 Brazil | Identify strategies to prevent violence in pre-hospital services | Mixed methods | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Carvalho K, Araujo P, Santos F, Oliveira P, Silva J, Santos K., 2023 Brazil | To analyze violence in work environments among nurses in the context of primary care | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Florido H, Duarte S, Floresta W, Fonseca A, Broca A., 2020 Brazil | To identify situations of violence in the work routine of health professionals and describe coping strategies | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

| Practical implementation strategies | ||||

| Ming, J, Huang H, Hung S, Chang C. Hsu Y., 2019 China | Effectiveness of situational simulation training with respect to nurses’ self-concept and self-confidence to cope with violence in work settings | Quasi-experimental study | Simulation and application of questionnaires in focus groups | Satisfactory quality |

| Ye J, et al., 2020 China | To evaluate the effectiveness of a training program on de-escalation techniques for nurses working in psychiatric units | Randomized controlled trial | Training in the application of de-escalation techniques | Good quality |

| Cai J, et al, 2023 China | To formulate a step-by-step approach to violence prevention strategies in work settings under the guidance of situational prevention theory and elements drawn from nurses | Quasi-experimental study | Application of strategies through classroom classes and simulation | Satisfactory quality |

| Zhang Y, Cai J, Qin Z, Wang H, Hu X., 2023 China | To investigate the impact of a digital platform on the incidence, severity, and coping with violence for nurses | Quasi-experimental study | Education and training platform | Good quality |

| Liao L, et al., 2024 China | Test the effect, feasibility, and acceptability of the Comprehensive Active Resilience Education (CARE) program in improving the resilience of emergency nurses exposed to workplace violence | Quasi-experimental study | Education and training platform | Good quality |

| Hsieh H, Huang I, Liu Y, Chen W, Lee Y, Hsu H., 2020 Taiwan | Compare the effectiveness of a biofeedback training phone (SDBT) and biofeedback training application among nurses who have experienced workplace violence by patients | Quasi-experimental, pre–post-test study | Tool for BT training and SDBT training. | Satisfactory quality |

| Chang Y. Hsu M. Ouyang W., 2022 Taiwan | To evaluate the effects of a novel integrated patient and visitor violence prevention and management training program | Quasi-experimental | 12-session training | Good quality |

| Hendrickson S., 2022 United States | Explore one hospital’s journey to understand the implementation of mitigation strategies against violence in work settings | Implementation and follow-up strategy | Development, implementation, and training on strategies against workplace violence | Good quality |

| de la Fuente, M., et al., 2019 United States | Evaluate the impact of behavior management training on nurses’ confidence in managing aggressive patients | Quasi-experimental, pre–post-test study | Training in behavior management | Good quality |

| Poore J, Mays C, McKibban L, Harbert Z, Schroedle K., 2024 United States. | Explore the development and implementation of de-escalation training for nurses entering work settings | Simulation with qualitative and quantitative approaches to research | Conflict de-escalation simulation | Good quality |

| Quigley, E, et al., 2021 United States | Development of standardized strategies to enhance the professional advancement and safety of healthcare workers | Implementation and follow-up strategy | Development, implementation, and training on strategies | Good quality |

| Luck L, Kaczorowski K, White M, Dickens G, McDermid F., 2023 Australia | Explore the experiences of nurses in implementing and modifying “safewards” (conflict mitigation) interventions | Participatory action research | Conflict mitigation interventions | Good quality |

| Mikkola R, Huhtala H, Paavilainen E., 2019 Finland | To develop a model of work-related fear coping in emergency department staff with a focus on medical and nursing staff | Cross-sectional study | Survey application | Good quality |

| Burkoski V, Farshait N, Yoon J, Clancy P, Fernandes K, Howell M., 2019 Canada | To explore nurses’ experiences with implementing technology-based violence prevention interventions | Qualitative study | Semi-structured interviews | Good quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-González, G.; Rebolledo-Ríos, D.; Osorio-Spuler, X.; Rudner, N.; Peña-Barra, C. Violence Against Nurses: Personal and Institutional Coping Strategies—A Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091166

González-González G, Rebolledo-Ríos D, Osorio-Spuler X, Rudner N, Peña-Barra C. Violence Against Nurses: Personal and Institutional Coping Strategies—A Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091166

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-González, Greys, Darling Rebolledo-Ríos, Ximena Osorio-Spuler, Nancy Rudner, and Constanza Peña-Barra. 2025. "Violence Against Nurses: Personal and Institutional Coping Strategies—A Scoping Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091166

APA StyleGonzález-González, G., Rebolledo-Ríos, D., Osorio-Spuler, X., Rudner, N., & Peña-Barra, C. (2025). Violence Against Nurses: Personal and Institutional Coping Strategies—A Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091166