On the Continuum of Foundational Validity: Lessons from Eyewitness Science for Latent Fingerprint Examination

Abstract

1. On the Continuum of Foundational Validity: Lessons from Eyewitness Science for Latent Fingerprint Examination

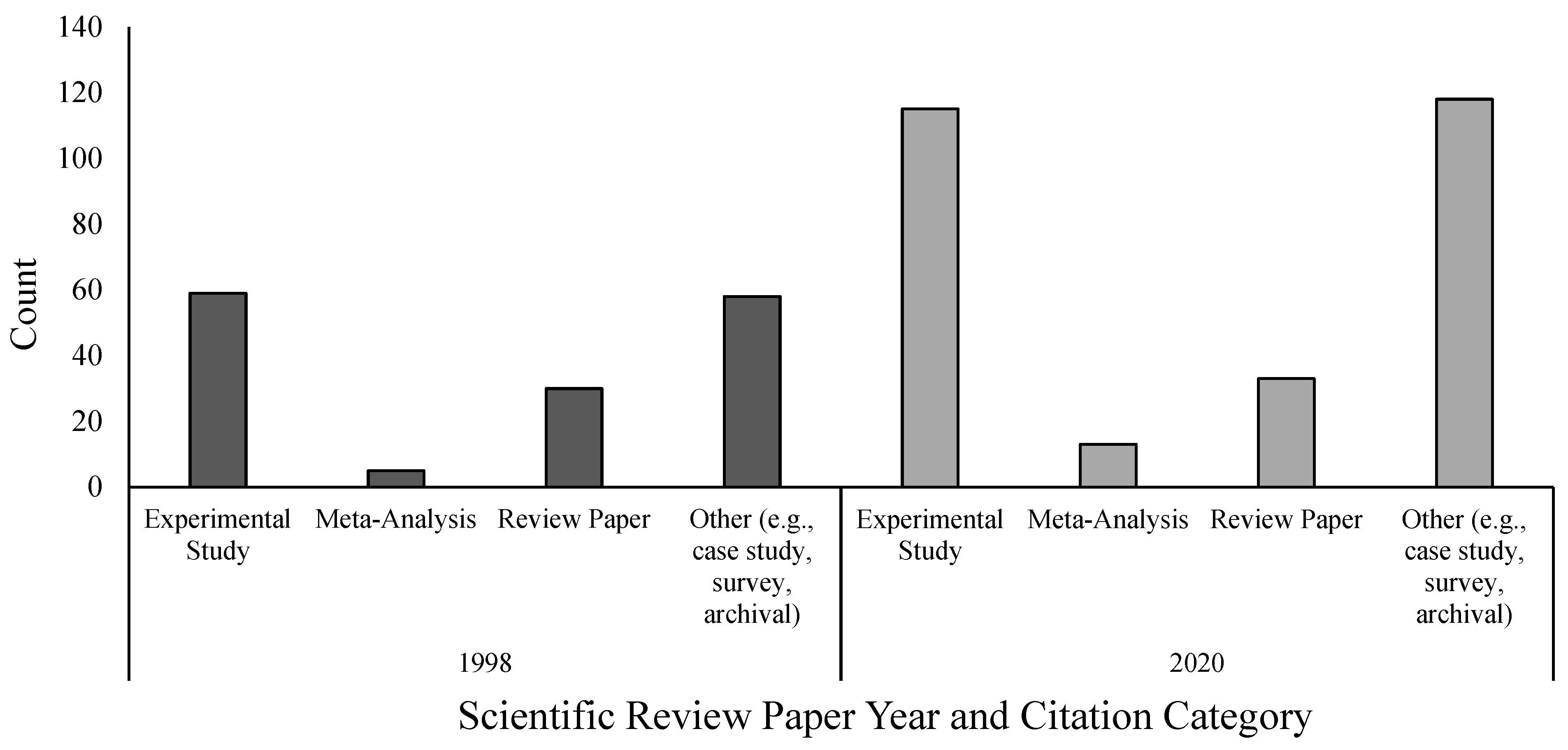

2. Where Does Eyewitness Science Lie on the Foundational Validity Continuum?

3. Where Does Latent Fingerprint Examination Lie on the Foundational Validity Continuum?

- Evaluations of techniques used to lift and process latent fingerprints at crime scenes (e.g., a review by Dhaneshwar et al., 2021);

- Studies examining the use of algorithms or databases to support LPE (e.g., image quality assessment; Varga, 2022);

- Statistical models that quantify the value of any LPE results (Neumann et al., 2015; Swofford et al., 2018);

- Textbooks and training materials that are used to introduce trainees to the field (e.g., Ashbaugh, 1999; Holder et al., 2011).

4. Conclusions

4.1. What Is Known About Latent Fingerprint Examination Is Based on a Nascent Empirical Literature

4.2. Latent Fingerprint Examination Does Not Have a Standardized Methodology

4.3. Lessons from Eyewitness Reform and the Path Forward for Latent Prints

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Black-box studies test forensic examiner performance only—the decision processes and reasoning of the examiners are not evaluated, just the final decisions. PCAST stated that these were studies in which “many examiners are given the same test items and asked to reach conclusions, without information about the ground truth or about the responses of other examiners. The study measures how often examiners reach correct conclusions, erroneous conclusions, and inconclusive results.” (PCAST, 2016, p. 6). PCAST also specified that the materials and procedures should closely resemble casework. |

References

- AAFS Standards Board. (2022). ANSI/ASB best practice recommendation 144: Best practice recommendations for the verification component in friction ridge examination. American Academy of Forensic Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Ashbaugh, D. R. (1999). Quantitative-qualitative friction ridge analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced ridgeology. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Busey, T., Heise, N., Hicklin, R. A., Ulery, B. T., & Buscaglia, J. (2021). Characterizing missed identifications and errors in latent fingerprint comparisons using eye-tracking data. PLoS ONE, 16(5), e0251674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busey, T., Silapiruiti, A., & Vanderkolk, J. (2014). The relation between sensitivity, similar non-matches and database size in fingerprint database searches. Law, Probability, and Risk, 13, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, S. D., & Wells, G. L. (2007). Eyewitness lineups: Is the appearance-change instruction a good idea? Law and Human Behavior, 31(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, J. M., & Ibaviosa, C. M. (2022). Beyond CSI: Calibrating public beliefs about the reliability of forensic science through openness and transparency. Science & Justice, 62(3), 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J., Bennett, E. A., & Sukel, H. L. (1996). Complex scientific testimony: How do jurors make decisions? Law and Human Behavior, 20(4), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, R. J., DeCoster, J., Harris, P. B., Fletcher, L. M., & Brodsky, S. L. (2011). A confidence-credibility model of expert witness persuasion: Mediating effects and implications for trial consultation. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 63(2), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubert v. Merrel Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (1993). 509 U.S. 579.

- de Keijser, J., & Elffers, H. (2012). Understanding of forensic expert reports by judges, defense lawyers and forensic professionals. Psychology, Crime & Law, 18(2), 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaneshwar, R., Kaur, M., & Kaur, M. (2021). An investigation of latent fingerprinting techniques. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Science, 11(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, I. E., & Kukucka, J. (2021). Linear Sequential Unmasking-Expanded (LSU-E): A general approach for improving decision making as well as minimizing noise and bias. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 3, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, H. (2019). Juror comprehension of forensic expert testimony: A literature review and gap analysis. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 1, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 702. (2023). Federal rules of evidence, testimony by expert witnesses, 702. Available online: https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/2025-02/federal-rules-of-evidence-dec-1-2024_0.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Frye v. United States. (1923). 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923).

- Gardner, B. O., Kelley, S., & Neuman, M. (2021). Latent print comparisons and examiner conclusions: A field analysis of case processing in one crime laboratory. Forensic Science International, 319, 110642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, B. L., Liu, A., Kafadar, K., Yaffe, J., & Dodson, C. S. (2021). Factoring the role of eyewitness evidence in the courtroom. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 17(3), 556–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, R. L., Quigley-McBride, A., Bluestine, M. B., & Garrett, B. (2024). Psychological science from research to policy: Eyewitness identifications in Pennsylvania police agencies. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 30(4), 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growns, B., Dunn, J. D., Mattijssen, J. A. T., Quigley-McBride, A., & Towler, A. (2022). Match me if you can: Evidence for a domain-general visual comparison ability. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 29, 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growns, B., & Kukucka, J. (2021). The prevalence effect in fingerprint identification: Match and non-match base-rates impact misses and false alarms. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(3), 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Growns, B., Towler, A., & Martire, K. A. (2023). The novel object-matching test (NOM test): A psychometric measure of visual comparison ability. Behavior Research Methods, 56, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, R. N., & Haber, L. (2014). Experimental results of fingerprint comparisons validity and reliability: A review and critical analysis. Science & Justice, 54(5), 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicklin, R. A., Richetelli, N., Taylor, A., & Buscaglia, J. (2025). Accuracy and reproducibility of latent print decision on comparisons from searches of an automated fingerprint identification system. Forensic Science International, 370, 112457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holder, E. H., Robinson, L. O., & Laub, J. H. (2011). The fingerprint sourcebook (Chapters 9.1–9.26). Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice.

- Horry, R., Memon, A., Wright, D. B., & Milne, R. (2012). Predictors of eyewitness identification decisions from video lineups in England: A field study. Law and Human Behavior, 36(4), 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocence Project. (2025). Eyewitness misidentification. Available online: https://innocenceproject.org/eyewitness-misidentification/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Kassin, S. M., Dror, I. E., & Kukucka, J. (2013). The forensic confirmation bias: Problems, perspectives, and proposed solutions. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassin, S. M., Ellsworth, P. C., & Smith, V. L. (1989). The “general acceptance” of psychological research on eyewitness testimony: A survey of the experts. American Psychologist, 44(8), 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassin, S. M., Tubb, V. A., Hosch, H. M., & Memon, A. (2001). On the “general acceptance” of eyewitness testimony research. A new survey of the experts. The American Psychologist, 56(5), 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, S., Gardner, B. O., Murrie, D. C., Pan, K. D., & Kafadar, K. (2020). How do latent print examiners perceive proficiency testing? An analysis of examiner perceptions, performance, and print quality. Science & Justice, 60(2), 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehler, J. J., & Liu, S. (2021). Fingerprint error rate on close non-matches. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 66(1), 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koertner, A. J., & Swofford, H. J. (2018). Comparison of latent print proficiency tests with latent prints obtain in routine casework using automatic and objective quality metrics. Journal of Forensic Identification, 68(3), 379. [Google Scholar]

- Kukucka, J., & Dror, I. E. (2023). Human factors in forensic science: Psychological causes of bias and error. In D. DeMatteo, & K. C. Scherr (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of psychology and law (pp. 621–642). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenburg, G., Champod, C., & Genessay, T. (2012). Informing the judgments of fingerprint analysts using quality metric and statistical assessment tools. Forensic Science International, 219(1–3), 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenburg, G., Champod, C., & Wertheim, P. (2009). Testing for potential contextual bias effects during the verification stage of the ACE-V methodology when conducting fingerprint comparisons. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 54(3), 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Penrod, S. D. (2022). Three-level meta-analysis of the other-race bias in facial identification. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 36(5), 1106–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K., Wu, D., Ai, L., & Luo, Y. (2021). The influence of close non-match fingerprints similar in delta regions of whorls on fingerprint identification. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 66(4), 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R. C., & Wells, G. L. (1985). Improving eyewitness identifications from lineups: Simultaneous versus sequential lineup presentation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(3), 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R. C., Wells, G. L., & O’Connor, F. J. (1989). Mock-juror belief of accurate and inaccurate eyewitnesses: A replication and extension. Law and Human Behavior, 13(3), 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12(4), 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, E. F., & Greene, E. (1980). Warning: Even memory for faces may be contagious. Law and Human Behavior, 4(4), 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25(12), 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, C. A., & Brigham, J. C. (2001). Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: A meta-analytic review. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7(1), 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, P. F., Arndorfer, A., & Charman, S. D. (2013). Appearance-change instruction effects on eyewitness lineup identification accuracy are not moderated by amount of appearance change. Law and Human Behavior, 37(6), 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council. (2009). Strengthening forensic science in the United States: A path forward. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, C., Champod, C., Yoo, M., Genessay, T., & Langenburg, G. (2015). Quantifying the weight of fingerprint evidence through the spatial relationship, directions and types of minutiae observed on fingermarks. Forensic Science International, 248, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, I., Cerchiai, B., & Stoiloff, S. (2014). Miami-Dade research study for the reliability of the ACE-V process: Accuracy & precision in latent fingerprint examinations [Unpublished Report]. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs.

- President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. (2016). Forensic science in criminal courts: Ensuring scientific validity of feature-comparison methods. Executive Office of the President.

- Quigley-McBride, A., Dror, I. E., Roy, T., Garrett, B. L., & Kukucka, J. (2022). A practical tool for information management in forensic decisions: Using Linear Sequential Unmasking-Expanded (LSU-E) in casework. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 4, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley-McBride, A., & Wells, G. L. (2018). Fillers can help control for contextual bias in forensic comparison tasks. Law and Human Behavior, 42(4), 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley-McBride, A., & Wells, G. L. (2023). Eyewitness confidence and decision time reflect identification accuracy in actual police lineups. Law and Human Behavior, 47(2), 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risinger, D. M., Saks, M. J., Thompson, W. C., & Rosenthal, R. (2002). The Daubert/Kumho implications of observer effects in forensic science: Hidden problems of expectation and suggestion. California Law Review, 90(1), 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurich, N., Albright, T. D., Stout, P., Eudaley, D., Neuman, M., & Hundl, C. (2025). The Hawthorne effect in studies of firearm and toolmark examiners. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 70(4), 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale-Carlisle, T. M., Colloff, M. F., Flowe, H. D., Wells, W., Wixted, J. T., & Mickes, L. (2019). Confidence and response time as indicators of eyewitness identification accuracy in the lab and in the real world. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 8(4), 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale-Carlisle, T. M., Quigley-McBride, A., Teitcher, J. E. F., Crozier, W. E., Dodson, C. S., & Garrett, B. L. (2024). New insights on expert opinion about eyewitness memory research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17456916241234837, advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steblay, N. K., & Wells, G. L. (2020). Assessment of bias in police lineups. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26(4), 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, H. S., Cuellar, M., & Kaye, D. (2019). Reliability and validity of forensic science evidence. Significance, 16(2), 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swofford, H. J., Koertner, A. J., Zemp, F., Ausdemore, M., Liu, A., & Salyards, M. J. (2018). A method for the statistical interpretation of friction ridge skin impression evidence: Method development and validation. Forensic Science International, 287, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swofford, H. J., Lund, S., Iyer, H., Butler, J., Soons, J., Thompson, R., Desiderio, V., Jones, J. P., & Ramotowski, R. (2024). Inconclusive decisions and error rates in forensic science. Forensic Science International: Synergy, 8, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangen, J. M., Thompson, M. B., & McCarthy, D. J. (2011). Identifying fingerprint expertise. Psychological Science, 22(8), 995–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Buscaglia, J., & Roberts, M. A. (2011). Accuracy and reliability of forensic latent fingerprint decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(19), 7733–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Buscaglia, J., & Roberts, M. A. (2012). Repeatability and reproducibility of decisions by latent fingerprint examiners. PLoS ONE, 7(3), e32800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Kiebuzinski, G. I., Roberts, M. A., & Buscaglia, J. (2013). Understanding the sufficiency of information for latent fingerprint value determinations. Forensic Science International, 230(1–3), 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Roberts, M. A., & Buscaglia, J. (2014). Measuring what latent fingerprint examiners consider sufficient information for individualization determinations. PLoS ONE, 9(11), e110179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Roberts, M. A., & Buscaglia, J. (2015). Changes in latent fingerprint examiners’ markup between analysis and comparison. Forensic Science International, 247, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Roberts, M. A., & Buscaglia, J. (2016). Interexaminer variation of minutia markup on latent fingerprints. Forensic Science International, 264, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, B. T., Hicklin, R. A., Roberts, M. A., & Buscaglia, J. (2017). Factors associated with latent fingerprint exclusion determinations. Forensic Science International, 275, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderkolk, J. R. (2011). Chapter 9: Examination process. In E. H. Holder, L. O. Robinson, & J. H. Laub (Eds.), The fingerprint sourcebook (Chapters 9.1–9.26). Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, USA. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/225320.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Varga, D. (2022). No-reference image quality assessment with convolutional neural networks and decision fusion. Applied Sciences, 12(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L. (1978). Applied eyewitness-testimony research: System variables and estimator variables. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(12), 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L. (2020). Psychological science on eyewitness identification and its impact on police practices and policies. American Psychologist, 75(9), 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., Kovera, M. B., Douglass, A. B., Brewer, N., Meissner, C. A., & Wixted, J. T. (2020). Policy and procedure recommendations for the collection and preservation of eyewitness identification evidence. Law and Human Behavior, 44(1), 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., Leippe, M. R., & Ostrom, T. M. (1979a). Guidelines for empirically assessing the fairness of a lineup. Law and Human Behavior, 3(4), 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., Lindsay, R. C. L., & Ferguson, T. J. (1979b). Accuracy, confidence, and juror perceptions in eyewitness identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(4), 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., & Quigley-McBride, A. (2016). Applying eyewitness identification research to the legal system: A glance at where we have been and where we could go. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 5(3), 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., Rydell, S. M., & Seelau, E. P. (1993). The selection of distractors for eyewitness lineups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., Small, M., Penrod, S., Malpass, R. S., Fulero, S. M., & Brimacombe, C. A. E. (1998). Eyewitness identification procedures: Recommendations for lineups and photospreads. Law and Human Behavior, 22(6), 603–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. L., Steblay, N. K., & Dysart, J. E. (2015). Double-blind photo lineups using actual eyewitnesses: An experimental test of a sequential versus simultaneous lineup procedure. Law and Human Behavior, 39(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. M., Harris, C. R., & Wixted, J. T. (2020). Science is not a signal detection problem. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 117(11), 5559–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wixted, J. T., & Wells, G. L. (2017). The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: A new synthesis. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18(1), 10–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Elements of Procedures | Eyewitness Identification | Latent Print Examination |

|---|---|---|

| Crime Scene Data? | Memory of people present during or around the time of a crime event. | Latent fingerprint collected in connection with a crime. |

| Recommended Method? | Fair, double-blind lineup procedure with unbiased instructions. | ACE-V and any local standard operating procedures. |

| Expertise Required? | Yes—but laypersons are a type of face recognition/matching “expert”. | Yes—special training and experience required. |

| Goal? | Link a particular person to a crime event or criminal act. | Link a particular person to a crime event or criminal act. |

| End-Users? | Police, lawyers, people accused of crimes, judges, and jurors. | Police, lawyers, people accused of crimes, judges, and jurors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quigley-McBride, A.; Blackall, T.L. On the Continuum of Foundational Validity: Lessons from Eyewitness Science for Latent Fingerprint Examination. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091145

Quigley-McBride A, Blackall TL. On the Continuum of Foundational Validity: Lessons from Eyewitness Science for Latent Fingerprint Examination. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091145

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuigley-McBride, Adele, and T. L. Blackall. 2025. "On the Continuum of Foundational Validity: Lessons from Eyewitness Science for Latent Fingerprint Examination" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091145

APA StyleQuigley-McBride, A., & Blackall, T. L. (2025). On the Continuum of Foundational Validity: Lessons from Eyewitness Science for Latent Fingerprint Examination. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091145