When Expertise Goes Undercover: Exploring the Impact of Perceived Overqualification on Knowledge Hiding and the Mediating Role of Future Work Self-Salience

Abstract

1. Introduction

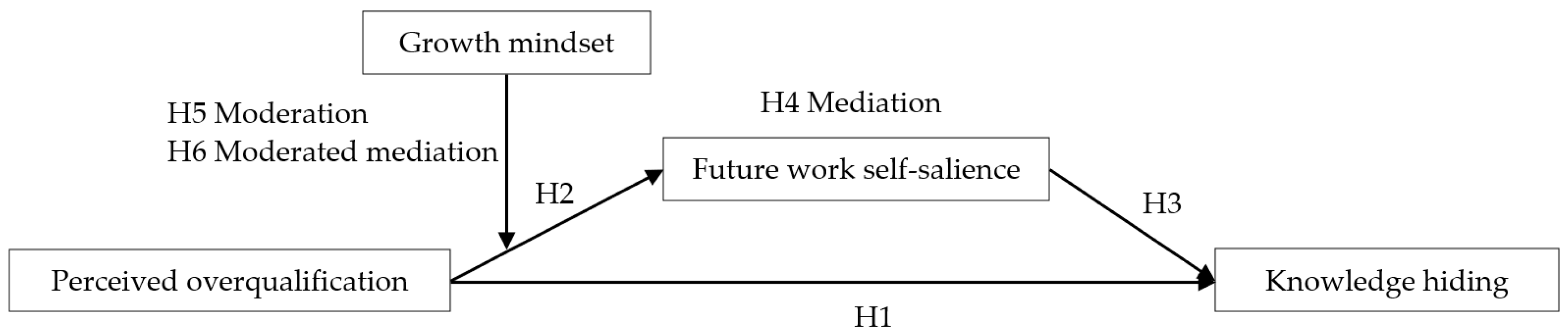

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Perceived Overqualification and Knowledge Hiding

2.2. The Mediating Effect of Future Work Self-Salience

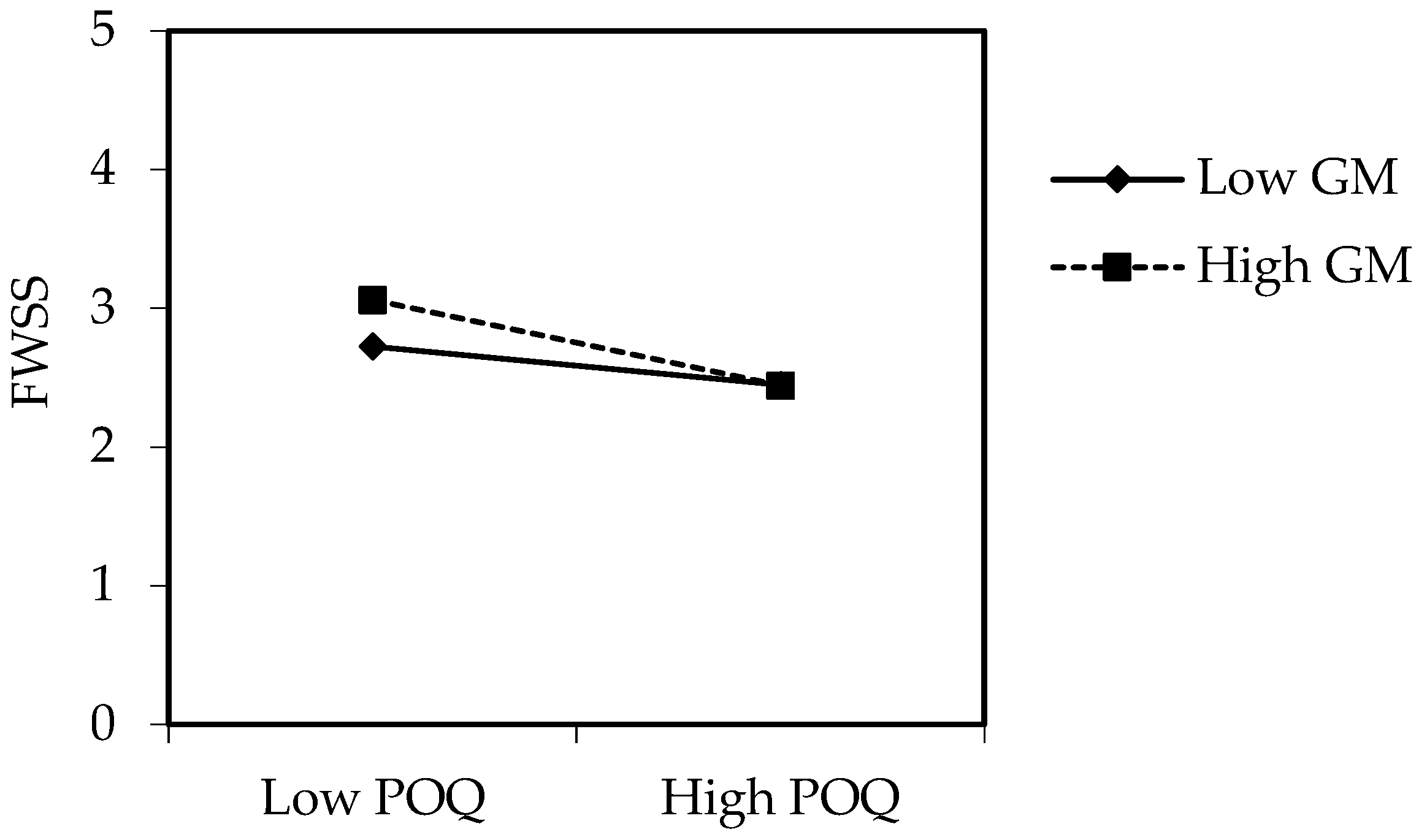

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Growth Mindset

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Perceived Overqualification (Time 1)

3.2.2. Growth Mindset (Time 1)

3.2.3. Future Work Self-Salience (Time 2)

3.2.4. Knowledge Hiding (Time 3)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Perceived overqualification (Johnson & Johnson, 1997) |

| 1. My work experience is more than necessary to do my present job (我的工作经验对我现在的工作来说绰绰有余) 2. My talents are not fully utilized on my job (我现在的工作并不能充分发挥我所有的才能) 3. My formal education overqualifies me for my present job (我的教育水平高于目前工作的要求) 4. Based on my skills, I am overqualified for the job I hold (我所拥有的工作技能高于这份工作的要求) |

| Future work self-salience (Strauss et al., 2012) |

| 1. I am very clear about who and what I want to become in my future work (我非常清楚自己在未来工作中想成为什么样的人) 2. This future is very easy for me to imagine (这一未来对我来说非常容易想象) 3. What type of future I want in relation to my work is very clear in my mind (我对自己在工作方面想要的未来非常清晰) 4. I can easily imagine my future work self (我很容易想象出未来工作中的自己) 5. The mental picture of this future is very clear (我脑海里对这个未来的画面非常清晰) |

| Growth mindset (Dweck et al., 1995) |

| 1. Everyone, no matter who they are, can significantly change their basic characteristics (无论是谁,每个人都可以显著地改变自己的基本特质) 2. No matter what kind of person someone is, they can always change very much (无论现在是什么样的人,人们总是可以有很大的改变) 3. All people can change even their most basic qualities (所有人都可以改变,即使是他们最基础的特质) 4. People can always substantially change the kind of person they are (人们总是可以极大地改变他们的特征特质) 5. As much as I hate to admit it, you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. People can’t really change their deepest attributes Reversed (虽然我不愿承认,但本性难移,人们无法真正改变他们最深层的特质) 6. Everyone is a certain kind of person, and there is not much that can be done to really change that Reversed (每个人都有其固有特质,很难真正去改变它) 7. The kind of person someone is, is something very basic about them and it can’t be changed very much Reversed (一个人的特质是他们最根本的东西,很难有大的改变) 8. People can do things differently, but the important parts of who they are can’t really be changed Reversed (人们可以有着不同的做事方式,但他们的核心特质很难改变) |

| Knowledge hiding (Connelly et al., 2012) |

| 1. Agreed to help him/her but never really intended to (同意帮助他/她,但却从来没有打算真的帮忙) 2. Agreed to help him/her but instead gave him/her information different from what s/he wanted (同意帮助他/她,但提供的信息不是他/她想要的) 3. Told him/her that I would help him/her out later but stalled as much as possible (告诉他/她我稍后会帮助他/她,但是能拖一时是一时) 4. Offered him/her some other information instead of what he/she really wanted (给他/她提供一些其他信息,而不是他/她真的想要的信息) 5. Pretended that I did not know the information (假装我不知道那些信息) 6. Said that I did not know, even though I did (即使我知道那些信息,我也会告诉他/她我不知道) 7. Pretended I did not know what s/he was talking about (假装我不知道他/她在说什么) 8. Said that I was not very knowledgeable about the topic (告诉他/她我对这个话题也不是很了解) 9. Explained that I would like to tell him/her, but was not supposed to (解释说我想要告诉他/她,但我不应该这样做) 10. Explained that the information is confidential and only available to people on a particular project (解释说这一信息是机密信息,只有属于这个特定项目的人才能知道) 11. Told him/her that my boss would not let anyone share this knowledge (告诉他/她我的领导不希望让其他人知道这信息) 12. Said that I would not answer his/her questions (告诉他/她我不能回答他/她的问题) |

References

- Anand, A., Offergelt, F., & Anand, P. (2022). Knowledge hiding—A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(6), 1438–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B. (2000). Role transitions in organizational life: An identity-based perspective. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., Grant, A. M., Kurkoski, J., & Welle, B. (2023). Getting unstuck: The effects of growth mindsets about the self and job on happiness at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(1), 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogilović, S., Černe, M., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017). Hiding behind a mask? Cultural intelligence, knowledge hiding, and individual and team creativity. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(5), 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z., Guan, Y., Li, H., Shi, W., Guo, K., Liu, Y., Li, Q., Han, X., Jiang, P., Fang, Z., & Hua, H. (2015). Self-esteem and proactive personality as predictors of future work self and career adaptability: An examination of mediating and moderating processes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B., Zhou, X., Guo, G., & Yang, K. (2020). Perceived overqualification and cyberloafing: A moderated-mediation model based on equity theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 164(3), 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C. E., Erne, M., Dysvik, A., & Kerlavaj, M. (2019). Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R. (2008). 4 person–environment fit in organizations: An assessment of theoretical progress. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 167–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A. N., Dagher, G. K., Lythreatis, S., & Azakir, M. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding: The roles of HR practices, organizational support for creativity, creativity, innovative work behavior, and task performance. Journal of Business Research, 140, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2021). Overqualification at work: A review and synthesis of the literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., Karaeminogullari, A., Bauer, T. N., & Ellis, A. M. (2020). Perceived overqualification at work: Implications for extra-role behaviors and advice network centrality. Journal of Management, 46(4), 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y., Zhuang, M., Cai, Z., Ding, Y., Wang, Y., Huang, Z., & Lai, X. (2017). Modeling dynamics in career construction: Reciprocal relationship between future work self and career exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 101, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Mao, J. Y., Huang, Q., & Zhang, G. (2022). Polishing followers’ future work selves! The critical roles of leader future orientation and vision communication. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 137, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Gabriel, M., & Patel, V. (2015). Amos covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Social Science Electronic Publishing, 13(2), 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. J., & Stieha, V. (2020). Growth mindset for human resource development: A scoping review of the literature with recommended interventions. Human Resource Development Review, 19(3), 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, B., Manapragada, A., & Viswesvaran, C. (2017). Who thinks they’re a big fish in a small pond and why does it matter? A meta-analysis of perceived overqualification. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102(10), 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G., & Li, W. (2024). The Paradox of excess: How perceived overqualification shapes innovative behavior through self-concept. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17487–17499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, P. A., Keating, L. A., & Ashford, S. J. (2020). How being in learning mode may enable a sustainable career across the lifespan. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S., De Clercq, D., & Fatima, T. (2020). Organizational injustice and knowledge hiding: The roles of organizational dis-identification and benevolence. Management Decision, 59(2), 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G. J., & Johnson, W. R. (1997). Perceived overqualification, emotional support, and health. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27(21), 1906–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J., Saeed, I., Fayaz, M., Zada, M., & Jan, D. (2023). Perceived overqualification? Examining its nexus with cyberloafing and knowledge hiding behavior: Harmonious passion as a moderator. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(2), 460–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. J., Park, J., Sohn, Y. W., & Lim, J. I. (2021). Perceived overqualification, boredom, and extra-role behaviors: Testing a moderated mediation model. Journal of Career Development, 48(4), 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., & Guay, R. P. (2011). Person–environment fit. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology: Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (Vol. 3). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. S., Liao, H., & Han, Y. (2021). I despise but also envy you: A dyadic investigation of perceived overqualification, perceived relative qualification, and knowledge hiding. Personnel Psychology, 75(1), 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H., Tian, J., & Cheng, B. (2024). Facilitation or hindrance: The contingent effect of organizational artificial intelligence adoption on proactive career behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 152, 108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Luksyte, A., Zhou, L. E., Shi, J., & Wang, M. O. (2015). Overqualification and counterproductive work behaviors: Examining a moderated mediation model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luksyte, A., Bauer, T. N., Debus, M. E., Erdogan, B., & Wu, C. H. (2022). Perceived overqualification and collectivism orientation: Implications for work and nonwork outcomes. Journal of Management, 48(2), 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B., & Zhang, J. (2022). Are overqualified individuals hiding knowledge: The mediating role of negative emotion state. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(3), 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D. C., & Parfyonova, N. M. (2013). Perceived overqualification and withdrawal behaviors: Examining the roles of job attitudes and work values. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(3), 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offergelt, F., & Venz, L. (2023). The joint effects of supervisor knowledge hiding, abusive supervision, and employee political skill on employee knowledge hiding behaviors. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(5), 1209–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W., Zhang, Q., Teo, T. S. H., & Lim, V. K. G. (2018). The dark triad and knowledge hiding. International Journal of Information Management, 42, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V., & Mohiya, M. (2021). Share or hide? Investigating positive and negative employee intentions and organizational support in the context of knowledge sharing and hiding. Journal of Business Research, 129(4), 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, X., Zhang, G., Tse, C. S., Feng, J., & Fan, W. (2022). When does daily job performance motivate learning behavior? The stimulation of high turnover rate. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(5), 1368–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W., Dong, X., & Liu, C. (2025). The impact of perceived overqualification on workplace procrastination: The role of public service motivation and perceived prosocial impact. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. J. (2017). Mismatch: How many workers with a bachelor’s degree are overqualified for their jobs? Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/mismatch-how-many-workers-bachelors-degree-are-overqualified-their-jobs (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Sales, A., Mansur, J., & Roth, S. (2023). Fit for functional differentiation: New directions for personnel management and organizational change bridging the fit theory and social systems theory. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 36(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2016). Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, I., Kalyar, M. N., Ahmad, B., & Pierscieniak, A. (2023). Moral exclusion in hospitality: Testing a moderated mediation model of the relationship between perceived overqualification and knowledge-hiding behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality, 35(30), 1759–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, K., & Kelly, C. (2016). An identity-based perspective on proactivity: Future work selves and beyond. In S. K. Parker, & U. K. Bindl (Eds.), Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organizations (pp. 330–354). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, B. J., & Blankemeyer, M. (2015). Future work self and career adaptability in the prediction of proactive career behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevelde, K., Baillien, E., & Notelaers, G. (2020). Person-environment fit as a parsimonious framework to explain workplace bullying. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(5), 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venz, L., & Nesher Shoshan, H. (2022). Be smart, play dumb? A transactional perspective on day-specific knowledge hiding, interpersonal conflict, and psychological strain. Human Relations, 75(1), 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Vázquez, G., Castro-Casal, C., & Álvarez-Pérez, D. (2023). Person–organization fit and helping behavior: How and when this relationship occurs. Current Psychology, 42(5), 3701–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J., & Strauss, K. (2024). How future work self salience shapes the effects of interacting with artificial intelligence. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 155, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M., & Wilson, T. D. (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125(5), 617–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z., Zhou, X., Wang, Q., & Liu, J. (2023). How perceived overqualification influences knowledge hiding from the relational perspective: The moderating role of perceived overqualification differentiation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(6), 1720–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. J., Law, K. S., & Lin, B. (2016). You think you are big fish in a small pond? Perceived overqualification, goal orientations, and proactivity at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Liao, J., Yan, Y., & Guo, Y. (2014). Newcomers’ future work selves, perceived supervisor support, and proactive socialization in Chinese organizations. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(9), 1457–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S., & Ma, C. (2023). Too smart to work hard? Investigating why overqualified employees engage in time theft behaviors. Human Resource Management, 62(6), 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POQ, FWSS, KH, GM | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| POQ, FWSS + KH, GM | 3.44 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| POQ + FWSS + KH, GM | 5.10 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.77 | 0.75 |

| POQ + FWSS + KH + GM | 10.55 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.42 |

| Construct | Estimate | SE | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POQ | ||||

| 1 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.91 |

| 2 | 0.73 | 0.02 | ||

| 3 | 0.78 | 0.03 | ||

| 4 | 0.77 | 0.02 | ||

| FWSS | ||||

| 1 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.92 |

| 2 | 0.76 | 0.02 | ||

| 3 | 0.71 | 0.02 | ||

| 4 | 0.77 | 0.02 | ||

| 5 | 0.80 | 0.02 | ||

| KH | ||||

| 1 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.96 |

| 2 | 0.73 | 0.03 | ||

| 3 | 0.75 | 0.03 | ||

| 4 | 0.73 | 0.02 | ||

| 5 | 0.75 | 0.02 | ||

| 6 | 0.76 | 0.02 | ||

| 7 | 0.70 | 0.03 | ||

| 8 | 0.73 | 0.03 | ||

| 9 | 0.73 | 0.03 | ||

| 10 | 0.75 | 0.02 | ||

| 11 | 0.70 | 0.03 | ||

| 12 | 0.69 | 0.03 | ||

| GM | ||||

| 1 | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.95 |

| 2 | 0.78 | 0.02 | ||

| 3 | 0.78 | 0.02 | ||

| 4 | 0.69 | 0.02 | ||

| 5 | 0.76 | 0.02 | ||

| 6 | 0.74 | 0.02 | ||

| 7 | 0.80 | 0.02 | ||

| 8 | 0.81 | 0.02 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 1.48 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| 2 Age | 33.72 | 5.66 | −0.07 | |||||||

| 3 Education | 3.18 | 0.65 | 0.004 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 4 Tenure | 8.24 | 4.64 | −0.001 | 0.64 *** | −0.07 | |||||

| 5 POQ | 3.14 | 0.89 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.06 | (0.85) | |||

| 6 FWSS | 2.90 | 0.77 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.004 | −0.26 *** | (0.87) | ||

| 7 KH | 2.91 | 0.54 | 0.02 | −0.001 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.29 *** | −0.28 *** | (0.93) | |

| 8 GM | 3.24 | 0.85 | 0.02 | −0.001 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.11 * | −0.01 | (0.92) |

| KH | FWSS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender | 0.02(0.05) | 0.001(0.05) | −0.13(0.07) | −0.12(0.07) | −0.11(0.07) |

| Age | 0.001(0.01) | 0.003(0.01) | 0.01(0.01) | 0.01(0.01) | 0.01(0.01) |

| Education | 0.03(0.04) | 0.03(0.04) | 0.06(0.05) | 0.07(0.05) | 0.07(0.05) |

| Tenure | −0.001(0.01) | −0.001(0.01) | −0.01(0.01) | −0.01(0.01) | −0.01(0.01) |

| Predictor variables | |||||

| POQ | 0.14(0.03) *** | −0.23(0.04) *** | −0.11(0.13) | ||

| GM | −0.001(0.03) | 0.12(0.04) ** | 0.45(0.13) ** | ||

| FWSS | −0.15(0.03) *** | ||||

| Interaction | |||||

| POQ × GM | −0.11(0.04) ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| F | 0.24 | 23.02 *** | 1.46 | 21.90 *** | 7.25 ** |

| POQ→FWSS→KH | ||

| Mediation of FWSS | Effect (SE) | 95%CI |

| Direct effect | 0.14 (0.03) | [0.09, 0.20] |

| Indirect effect | 0.04 (0.01) | [0.02, 0.06] |

| POQ→FWSS | ||

| Moderation of GM | Effect (SE) | 95%CI |

| Low GM | −0.16 (0.05) | [−0.25, −0.06] |

| High GM | −0.35 (0.08) | [−0.50, −0.20] |

| POQ→FWSS→KH | ||

| Moderated mediation | Effect (SE) | 95%CI |

| Low GM | 0.02 (0.01) | [0.01, 0.04] |

| High GM | 0.05 (0.02) | [0.03, 0.09] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, H. When Expertise Goes Undercover: Exploring the Impact of Perceived Overqualification on Knowledge Hiding and the Mediating Role of Future Work Self-Salience. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081134

Ren X, Wu D, Zhang Q, Lin H. When Expertise Goes Undercover: Exploring the Impact of Perceived Overqualification on Knowledge Hiding and the Mediating Role of Future Work Self-Salience. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081134

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Xiaoyun, Di Wu, Qian Zhang, and Haitianyu Lin. 2025. "When Expertise Goes Undercover: Exploring the Impact of Perceived Overqualification on Knowledge Hiding and the Mediating Role of Future Work Self-Salience" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081134

APA StyleRen, X., Wu, D., Zhang, Q., & Lin, H. (2025). When Expertise Goes Undercover: Exploring the Impact of Perceived Overqualification on Knowledge Hiding and the Mediating Role of Future Work Self-Salience. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081134