Comparing Gender Differences in Willingness to Accept Same- and Other-Sex Dyadic and Multi-Person Sexual Offers: An Examination of the Backlash Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Threesome Participation and the SDS

1.2. Sex, Gender, and the Backlash Effect

1.3. Stigma and Backlash in Same-Sex Sexual Behaviors

1.4. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures and Materials

2.2.1. Experimental Vignettes

2.2.2. Sexual Willingness Scale (SWS)

2.2.3. Anticipated Sexual Stigma Scale (ASSS)

2.2.4. Demographics

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Screening and Cleaning

3. Results

3.1. Anticipated Stigma

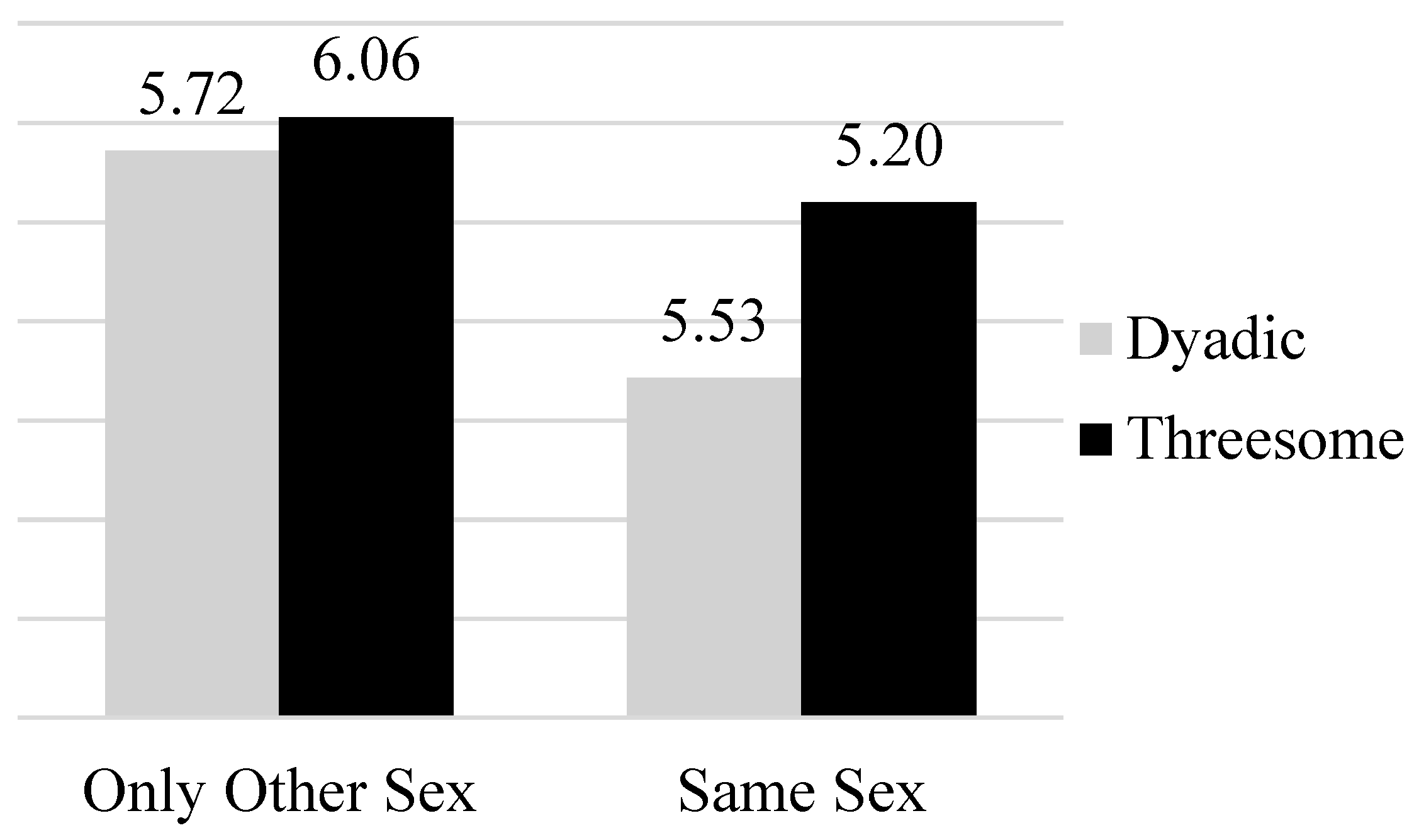

3.2. Willingness to Accept the Sexual Offer

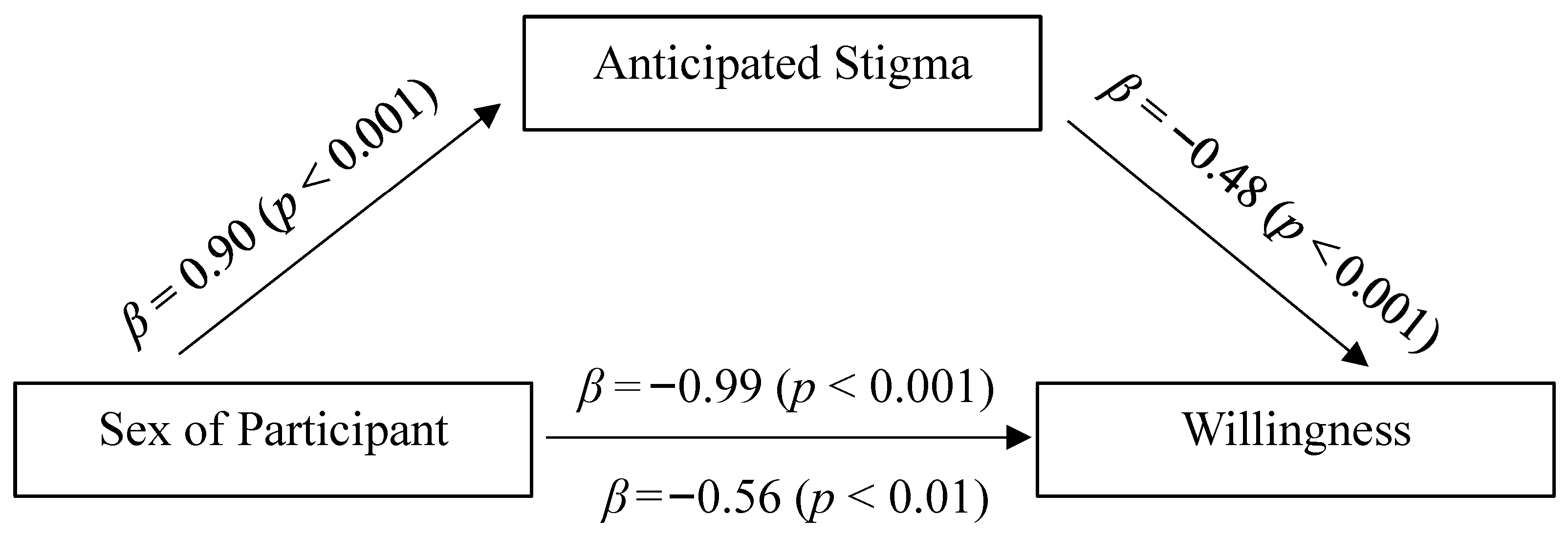

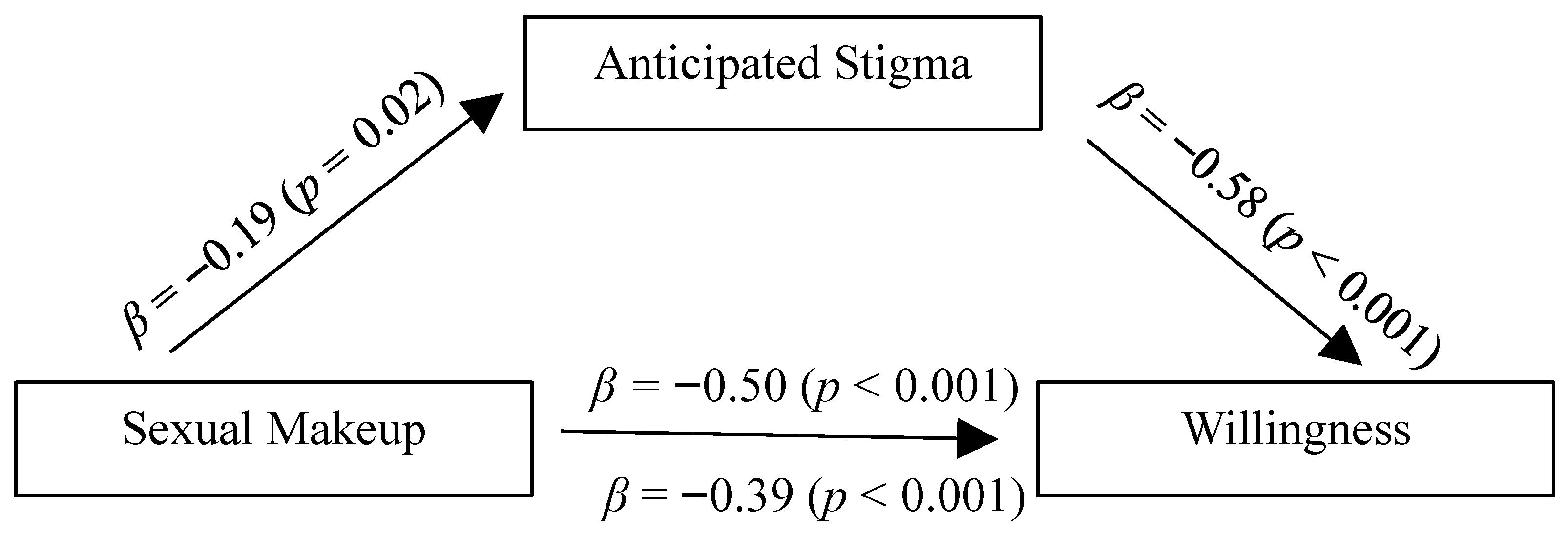

3.3. The Mediating Role of Anticipated Stigma

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amanatullah, E. T., & Morris, M. W. (2010). Negotiating gender roles: Gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. (2005). Orthodox and inclusive masculinity: Competing masculinities among heterosexual men in a feminized terrain. Sociological Perspectives, 48(3), 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. (2011). The rise and fall of western homohysteria. Journal of Feminist Scholarship, 1(1), 80–94. Available online: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol1/iss1/16 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Armstrong, E. A., England, P., & Fogarty, A. C. K. (2012). Accounting for women’s orgasm and sexual enjoyment in college hookups and relationships. American Sociological Review, 77(3), 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 347–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinsoli, M. L., Suppes, A., & Napier, J. L. (2020). Predictors of attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in 23 countries. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(5), 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, I., Peter, J., & van Oosten, J. M. F. (2016). Liking a sexual character affects willingness to have casual sex: The moderating role of relationship status and status satisfaction. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 28(2), 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L., Lucas, K. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2004). “The ball was always in his court”: An exploratory analysis of relationship scripts, sexual scripts, and condom use among African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(1), 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescoll, V. L., Okimoto, T. G., & Vial, A. C. (2018). You’ve come a long way… maybe: How moral emotions trigger backlash against women leaders. Journal of Social Issues, 74(1), 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, H., & Hoffman, A. (2018). ‘Straight with a pinch of bi’: The construction of heterosexuality as an elastic category among adult US men. Sexualities, 21(1–2), 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B., & Katayama, M. (1996). Assessment of sexual orientation in lesbian/gay/bisexual studies. Journal of Homosexuality, 30(4), 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., & Moors, A. C. (2013). Backlash from the bedroom: Stigma mediates gender differences in acceptance of casual sex offers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(3), 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L. M. (2008). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, M. L., Decker, M., & Littleton, H. L. (2024). The sexual scripts of transgender and gender diverse emerging adults: A thematic analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 48(2), 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, P., & Bearak, J. (2014). The sexual double standard and gender differences in attitudes toward casual sex among US university students. Demographic Research, 30, 1327–1338. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26348237 (accessed on 2 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fahs, B. (2014). Compulsory bisexuality?: The challenges of modern sexual fluidity. In Bisexuality and queer theory (pp. 239–257). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Finger, M. S., & Rand, K. L. (2003). Addressing validity concerns in clinical psychology research. In Handbook of research methods in clinical psychology (pp. 13–30). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, H., & Kitzinger, C. (2001). Reformulating sexual script theory: Developing a discursive psychology of sexual negotiation. Theory & Psychology, 11(2), 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Marugán, E. M., Felipe Castaño, M. E., Marugán de Miguelsanz, M., & Martín Antón, L. J. (2021). Are women still judged by their sexual behaviour? Prevalence and problems linked to sexual double standard amongst university students. Sexuality & Culture, 25(6), 1927–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Berrocal, C., Moyano, N., Álvarez-Muelas, A., & Sierra, J. C. (2022). Sexual double standard: A gender-based prejudice referring to sexual freedom and sexual shyness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1006675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmers, B. R., Harbke, C. R., & Herbstrith, J. C. (2018). Sexual willingness with same-and other-sex prospective partners: Experimental evidence from the bar scene. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158(1), 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensums, M., Overbeek, G., & Jorgensen, T. D. (2020). Not one sexual double standard but two? Adolescents’ attitudes about appropriate sexual behavior. Youth & Society, 54(1), 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly, 66(1), 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “Homophobia”: Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 1(2), 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T. (2011). Circuits of power, circuits of pleasure: Sexual scripting in gay men’s bottom narratives. Sexualities, 14(2), 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, V., Valsecchi, G., Berent, J., Borinca, I., & Falomir-Pichastor, J. M. (2021). The impact of masculinity beliefs and political ideologies on men’s backlash against non-traditional men: The moderating role of perceived men’s feminization. International Review of Social Psychology, 34, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K., & Marks, M. J. (2009). Common vs. uncommon sexual acts: Evidence for the sexual double standard. Sex Roles, 60, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, M. S. (1994). Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. In H. Brod, & M. Kaufman (Eds.), Theorizing masculinities (pp. 119–141). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, V., Imhoff, R., Reininger, K. M., & Briken, P. (2019). Perceptions of sexual script deviation in women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreager, D. A., Staff, J., Gauthier, R., Lefkowitz, E. S., & Feinberg, M. E. (2016). The double standard at sexual debut: Gender, sexual behavior and adolescent peer acceptance. Sex Roles, 75(7), 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, M. J., & Fraley, R. C. (2005). The sexual double standard: Fact or fiction? Sex Roles, 52, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsick, J. L., Kruk, M., Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., & Ziegler, A. (2021). Gender similarities and differences in casual sex acceptance among lesbian women and gay men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(3), 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, M., & Anderson, E. (2014). The influence of declining homophobia on men’s gender in the United States: An argument for the study of homohysteria. Sex Roles, 71, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R. (1994). Openness to Experience: Expanding the boundaries of Factor V. European Journal of Personality, 8(4), 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhausen, R. R., & Herold, E. S. (2002). Reconceptualizing the sexual double standard. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 13(2), 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., & Kray, L. J. (2022). The mitigating effect of desiring status on social backlash against ambitious women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 102, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, T. D., & Manago, B. (2018). Precarious sexuality: How men and women are differentially categorized for similar sexual behavior. American Sociological Review, 83(2), 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Johnson, E. R. (2016). Backlash against male elementary educators. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(7), 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11(2), 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). Disruptions in women’s self-promotion: The backlash avoidance model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(2), 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, L. J., Hagerman, C., Gnoleba, M. A., Erchull, M. J., Liss, M., Miles-McLean, H., & Robertson, C. M. (2015). Exploring perceptions of slut-shaming on Facebook: Evidence for a reverse sexual double standard. Gender Issues, 32, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, C. J. (2007). Dude, you’re a fag: Masculinity and sexuality in high school. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, G. E., Ward, D. B., & Brown, T. B. (2013). Relationship scripts: How young women develop and maintain same-sex romantic relationships. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9(2), 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reback, C. J., & Larkins, S. (2010). Maintaining a heterosexual identity: Sexual meanings among a sample of heterosexually identified men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, G. S. (1984). Thinking sex: Notes for a radical theory of politics of sexuality. In C. S. Vance (Ed.), Pleasure and danger: Exploring female sexuality (pp. 267–319). Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoats, R. (2020). Understanding threesomes: Gender, sex, and consensual non-monogamy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Scoats, R., Anderson, E., & White, A. J. (2021). Exploring gay men’s threesomes: Normalization, Concerns, and sexual opportunities. Journal of Bodies, Sexualities, and Masculinities, 2(2), 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoats, R., Joseph, L. J., & Anderson, E. (2018). ‘I don’t mind watching him cum’: Heterosexual men, threesomes, and the erosion of the one-time rule of homosexuality. Sexualities, 21(1–2), 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1984). Sexual scripts. Society, 22, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A. E., & Byers, E. S. (2021). An experimental investigation of variations in judgments of hypothetical males and females initiating mixed-gender threesomes: An application of sexual script theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A. E., Hart, J., Stefaniak, S., & Harvey, C. (2018). Exploring heterosexual adults’ endorsement of the sexual double standard among initiators of consensually nonmonogamous relationship behaviors. Sex Roles, 79, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A. E., Harvey, C. A., Haus, K. R., & Karst, A. (2020). An investigation of the implicit endorsement of the sexual double standard among US young adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A. E., Osborn, M., Gooch, K., & Ravet, M. (2022). An empirical investigation of variations in outcomes associated with heterosexual adults’ most recent mixed-sex threesome experience. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(6), 3021–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M., & Friese, M. (2024). Sexual (Double) Standards revisited: Similarities and differences in the societal evaluation of male and female sexuality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 16(5), 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wignall, L. (2022). Kinky in the digital age: Gay men’s subcultures and social identities. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2016). The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women’s implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 142(2), 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthen, M. G. (2013). An argument for separate analyses of attitudes toward lesbian, gay, bisexual men, bisexual women, MtF and FtM transgender individuals. Sex Roles, 68, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E. R., & Perry, B. L. (2006). Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. In Current issues in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health (pp. 81–110). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Anticipated Stigma M (SD) | Willingness M (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Participant | Other-Sex | Dyadic (N = 72) | 3.00 (1.05) | 5.44 (0.99) |

| MST (N = 76) | 3.03 (0.91) | 5.73 (0.92) | ||

| Same-Sex | Dyadic (N = 43) | 3.95 (1.18) | 3.71 (1.34) | |

| MST (N = 151) | 3.18 (0.98) | 5.06 (1.24) | ||

| Female Participant | Other-Sex | Dyadic (N = 41) | 4.25 (1.22) | 3.87 (1.23) |

| MST (N = 45) | 4.25 (1.28) | 3.86 (1.65) | ||

| Same-Sex | Dyadic (N = 37) | 4.48 (1.05) | 3.34 (1.43) | |

| MST (N = 75) | 4.21 (1.01) | 3.27 (1.31) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, A.E.; Bensen, L.; Scoats, R. Comparing Gender Differences in Willingness to Accept Same- and Other-Sex Dyadic and Multi-Person Sexual Offers: An Examination of the Backlash Effect. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081128

Thompson AE, Bensen L, Scoats R. Comparing Gender Differences in Willingness to Accept Same- and Other-Sex Dyadic and Multi-Person Sexual Offers: An Examination of the Backlash Effect. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081128

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Ashley E., Lizzy Bensen, and Ryan Scoats. 2025. "Comparing Gender Differences in Willingness to Accept Same- and Other-Sex Dyadic and Multi-Person Sexual Offers: An Examination of the Backlash Effect" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081128

APA StyleThompson, A. E., Bensen, L., & Scoats, R. (2025). Comparing Gender Differences in Willingness to Accept Same- and Other-Sex Dyadic and Multi-Person Sexual Offers: An Examination of the Backlash Effect. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081128