The Impact of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior Among Undergraduates: The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cyber-Ostracism and Its Impact

1.2. The Role of Bystanders in Cyber-Ostracism

1.3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

1.3.1. Cyber-Ostracism and Bystanders’ Helping Behavior

1.3.2. Rejection Sensitivity as a Moderator

1.4. Overview of the Present Research

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Participants and Design

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Manipulation of Cyber-Ostracism

2.2.2. Manipulation Checks of Cyber-Ostracism

2.2.3. Measurement of Rejection Sensitivity

2.2.4. Measurement of Bystanders’ Helping Behavior

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Results and Discussions

2.5.1. Statistical Descriptions and Correlations

2.5.2. Manipulation Checks

2.5.3. The Effect of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior

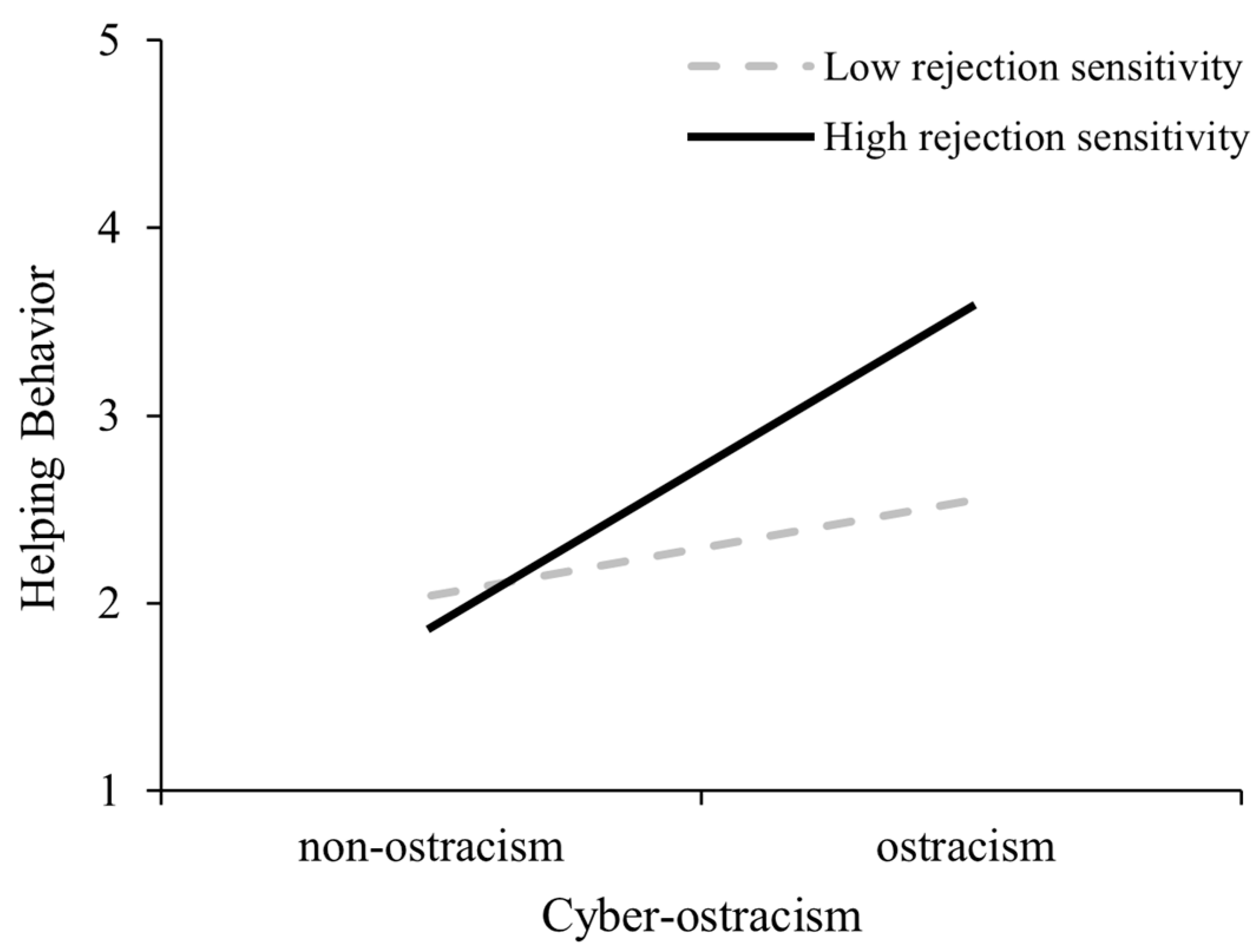

2.5.4. The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Participants and Design

3.2. Materials

3.2.1. Manipulation of Cyber-Ostracism

3.2.2. Manipulation Checks of Cyber-Ostracism

3.2.3. Measurement of Rejection Sensitivity

3.2.4. Measurement of Bystanders’ Helping Behavior

3.3. Procedures

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3.5. Results and Discussions

3.5.1. Statistical Descriptions and Correlations

3.5.2. Manipulation Checks

3.5.3. The Effect of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior

3.5.4. The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings and Contributions

4.1.1. Cyber-Ostracism Triggers Bystander Helping

4.1.2. The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bastiaensens, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2014). Cyberbullying on social network sites. An experimental study into bystanders’ behavioural intentions to help the victim or reinforce the bully. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, K. R., Gyurak, A., Ayduk, Ö., Downey, G., Garner, M. J., Mogg, K., Bradley, B. P., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Rejection sensitivity and disruption of attention by social threat cues. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, M. J., Chen, Z., Poon, K. T., Benfield, J. A., & Ng, H. K. (2018). Ostracized but why? Effects of attributions and empathy on connecting with the socially excluded. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0201183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondü, R., & Richter, P. (2016). Linking forms and functions of aggression in adults to justice and rejection sensitivity. Psychology of Violence, 6(2), 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, C. M., & Lutz, S. (2025). Coping with online versus offline exclusion: Ostracism context affects individuals’ coping intentions. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 18, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). (2023). The 51st statistical report on China’s Internet development. Available online: https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202307/P020230707514088128694.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Cialdini, R. B., Brown, S. L., Lewis, B. P., Luce, C., & Neuberg, S. L. (1997). Reinterpreting the empathy-altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, F., & Song, Y. (2017). Gratitude and college students’ helping behaviors: Mediating effect of empathy and its gender difference. Psychological Development and Education, 33(3), 289–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H., Zhu, L., Wei, H., Geng, J., Huang, F., & Lei, L. (2022). The relationship between cyber-ostracism and adolescents’ non-suicidal self-injury: Mediating roles of depression and experiential avoidance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Fu, R., Ooi, L. L., Coplan, R. J., Zheng, Q., & Deng, X. (2020). Relations between different components of rejection sensitivity and adjustment in Chinese children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 67, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, A. P. G., Marques, L. M., Lapenta, O. M., Asthana, M. K., Amodio, D., & Boggio, P. S. (2017). Ostracism via virtual chat room—Effects on basic needs, anger and pain. PLoS ONE, 12(9), e0184215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175−191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiset, J., Al Hajj, R., & Vongas, J. G. (2017). Workplace ostracism seen through the lens of power. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbava, S., Machackova, H., & Dedkova, L. (2021). Cyberostracism: Emotional and behavioral consequences in social media inter-actions. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal, 29(67), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F., Huang, J., Liu, T., & Gu, L. (2022). The moderation of bystanders’ social responsibility on their third-party punishment of intergroup vicarious exclusion. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 20(3), 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Zhang, P., Liao, J., & Wu, F. (2020). Social exclusion and green consumption: A costly signaling approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 535489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatun, O., & Demirci, İ. (2022). Developing the Cyberostracism Scale and examining its psychometric characteristics. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(2), 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X., Chu, X., Liu, Q., Zhou, Z., & Fan, C. (2019). Bystander behavior in cyberbullying. Advances in Psychological Science, 27(7), 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T., Wu, Y., Zhang, L., & Jia, Y. (2024). Cyber ostracism and online aggressive behavior among college students: The longitudinal moderating role of moral disengagement. Chinese Journal of Psychological Science, 47(6), 1373–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: Analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, J. I. (2008). From social projection to social behaviour. European Review of Social Psychology, 18(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y., Zhang, C., Niu, G., Tong, Y., Tian, Y., & Zhou, Z. (2018). The association between cyber-ostracism and depression: A moderated mediation model. Chinese Journal of Psychological Science, 41(1), 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S. R., Ayduk, O., & Downey, G. (2001). The role of rejection sensitivity in people’s relationships with significant others and valued social groups. In M. R. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection (pp. 251–289). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. (2007). A relative study of rejection sensitivity [Master’s thesis, Jiangxi Normal University]. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y., Liu, Y., & Cao, G. (2023). Effect of rejection sensitivity on aggressive behavior in college students: A moderated mediation model. China Journal of Health Psychology, 31(3), 474–480. [Google Scholar]

- London, B., Macdonald, J., & Inman, E. (2020). Invited reflection: Rejection sensitivity as a social-cognitive model of minority stress. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, S. (2022). Why don’t you answer me?! Exploring the effects of (repeated exposure to) ostracism via messengers on users’ fundamental needs, well-being, and coping motivation. Media Psychology, 26(2), 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, S., & Schneider, F. M. (2021). Is receiving dislikes in social media still better than being ignored? The effects of ostracism and rejection on need threat and coping responses online. Media Psychology, 24(6), 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M., Xiong, Y., Wang, H., Yang, L., Chen, J., & Ren, P. (2024). Why rejection sensitivity leads to adolescents’ loneliness: Differential exposure, reactivity, and exposure-reactivity models. Journal of Adolescence, 97(1), 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, C. L., Morelli, S. A., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2011). An fMRI investigation of empathy for ‘social pain’ and subsequent prosocial behavior. NeuroImage, 55(1), 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, G. F., Zhou, Z. K., Sun, X. J., Yu, F., Xie, X. C., Liu, Q. Q., & Lian, S. L. (2018). Cyber-ostracism and its relation to depression among Chinese adolescents: The moderating role of optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgren, L. F., Banas, K., & MacDonald, G. (2011). Empathy gaps for social pain: Why people underestimate the pain of social suffering. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(1), 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolini, D., Pagliaro, S., Alparone, F. R., Marotta, F., & van Beest, I. (2017). On vicarious ostracism: Examining the mediators of observers’ reactions towards the target and the sources of ostracism. Social Influence, 12(4), 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsnik, C., & Vorauer, J. D. (2020). Do dominant group members have different emotional responses to observing dominant-on-dominant versus dominant-on-disadvantaged ostracism? Some evidence for heightened reactivity to potentially discriminatory ingroup behavior. PLOS ONE, 15(6), e0234540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, K. T., Jiang, Y., & Teng, F. (2020). Putting oneself in someone’s shoes: The effect of observing ostracism on physical pain, social pain, negative emotion, and self-regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 166, 110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., Sun, Q., & Shao, A. (2025). The antecedent mechanism of cyber-ostracism based on qualitative analysis. Psychology: Techniques and Applications, 13(1), 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rudert, S. C., Ruf, S., & Greifeneder, R. (2020). Whom to punish? How observers sanction norm-violating behavior in ostracism situations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(2), 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudert, S. C., Sutter, D., Corrodi, V. C., & Greifeneder, R. (2018). Who’s to blame? Dissimilarity as a cue in moral judgments of observed ostracism episodes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(1), 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, F. M., Zwillich, B., Bindl, M. J., Hopp, F. R., Reich, S., & Vorderer, P. (2017). Social media ostracism: The effects of being excluded online. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C., Dai, C., Ma, H., & Zhao, X. (2023). The influence of cyber-ostracism on university students’ online deviant behaviors: Moderated mediation effect. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 29(2), 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L., Sun, P., Shi, J., Ye, H., & Tao, J. (2025). The effect of cyber-Ostracism on social anxiety among undergraduates: The mediating effects of rejection sensitivity and rumination. Behavioral Science, 15(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stukas, A. A., & Clary, E. G. (2012). Altruism and helping behavior. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (2nd ed., pp. 100–107). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q., Molenmaker, W., Liu, Y., & van Dijk, E. (2025). The effects of social exclusion on distributive fairness judgments and cooperative behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 64(2), 12810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Tong, Y., & Fan, C. (2017). Social exclusion and cyberostracism on depression: The mediating role of self-control. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 15(2), 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y., Hommel, B., & Ma, K. (2023). Vicarious ostracism reduces observers’ sense of agency. Consciousness and Cognition, 110, 103492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J., & Nesdale, D. (2012). Rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and loneliness in young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(8), 1984–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselmann, E. D., Wirth, J. H., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Williams, K. D. (2013). When do we ostracize. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(1), 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K. D. (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 41, pp. 279–314). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J., & Kuo, F. (2024). The effects of cyber-ostracism on college students’ aggressive behavior: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1393876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., & Zou, Y. (2020). Can we really empathize? The influence of vicarious ostracism on individuals and its theoretical explanation. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(9), 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Hu, N., Ding, X., & Li, J. (2021). The relationship between rejection sensitivity and borderline personality features: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 29(7), 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Li, X., Tian, L., & Huebner, E. S. (2020). Longitudinal association between low self-esteem and depression in early adolescents: The role of rejection sensitivity and loneliness. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 93(1), 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y., Yan, Y., & Zhang, D. (2025). The effects of observed ostracism on social avoidance: The role of fear of negative evaluation and rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 238, 113080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y., Wang, Y., Yang, X., & Jiang, R. (2022). Observed ostracism and compensatory behavior: A moderated mediation model of empathy and observer justice sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 198, 111829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cyber-Ostracism Group | Ostracism (N = 138) | Non-Ostracism (N = 138) | Total (N = 276) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | Median | M ± SD | Median | M ± SD | Median | |

| Rejection sensitivity | 56.48 ± 7.00 | 56.00 | 57.75 ± 8.56 | 57.00 | 57.12 ± 7.84 | 56.00 |

| Manipulation check scores | 2.71 ± 0.75 | 2.67 | 1.60 ± 0.62 | 1.67 | 2.16 ± 0.88 | 2.00 |

| Helping behavior | 3.08 ± 0.86 | 3.00 | 2.17 ± 0.94 | 2.00 | 2.62 ± 1.01 | 2.67 |

| Age | 19.74 ± 1.39 | 19.00 | 19.70 ± 1.53 | 19.00 | 19.72 ± 1.46 | 19.00 |

| Daily internet usage (hour) | 7.91 ± 2.98 | 8.00 | 7.30 ± 2.69 | 8.00 | 7.61 ± 2.85 | 8.00 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rejection sensitivity | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Cyber-ostracism | −0.02 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Manipulation check scores | 0.01 | 0.63 *** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Helping behavior | 0.07 | 0.45 *** | 0.55 *** | 1 | |||

| 5. Gender | 0.18 ** | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.004 | 1 | ||

| 6. Age | −0.13 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 1 | |

| 7. Daily internet usage (hour) | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.09 | 1 |

| Cyber-Ostracism Group | Ostracism (N = 129) | Non-Ostracism (N = 129) | Total (N = 258) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | Median | M ± SD | Median | M ± SD | Median | |

| Rejection sensitivity | 57.43 ± 9.27 | 60.00 | 57.96 ± 9.23 | 59.00 | 57.70 ± 9.24 | 60.00 |

| Manipulation check scores | 2.96 ± 0.80 | 3.00 | 1.67 ± 0.69 | 1.67 | 2.32 ± 0.99 | 2.00 |

| Helping behavior | 3.48 ± 1.66 | 3.00 | 2.64 ± 1.54 | 2.00 | 3.06 ± 1.65 | 3.00 |

| Age | 19.82 ± 1.49 | 19.00 | 20.02 ± 1.79 | 20.00 | 19.92 ± 1.64 | 19.00 |

| Daily internet usage (hour) | 7.50 ± 2.86 | 8.00 | 7.36 ± 2.92 | 8.00 | 7.43 ± 2.89 | 8.00 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rejection sensitivity | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Cyber-ostracism | −0.02 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Manipulation check scores | 0.24 *** | 0.67 *** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Helping behavior | 0.36 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.35 *** | 1 | |||

| 5. Gender | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 1 | ||

| 6. Age | −0.17 ** | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 1 | |

| 7. Daily internet usage (hour) | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Q.; Su, S.; Lai, S.; Ding, X.; Guo, S. The Impact of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior Among Undergraduates: The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081120

Sun Q, Su S, Lai S, Ding X, Guo S. The Impact of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior Among Undergraduates: The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081120

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Qian, Shuchang Su, Shuting Lai, Xi Ding, and Shaoyang Guo. 2025. "The Impact of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior Among Undergraduates: The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081120

APA StyleSun, Q., Su, S., Lai, S., Ding, X., & Guo, S. (2025). The Impact of Cyber-Ostracism on Bystanders’ Helping Behavior Among Undergraduates: The Moderating Role of Rejection Sensitivity. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1120. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081120