Music as Fluidum: A Rheological Approach to the Materiality of Sound as Movement Through Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

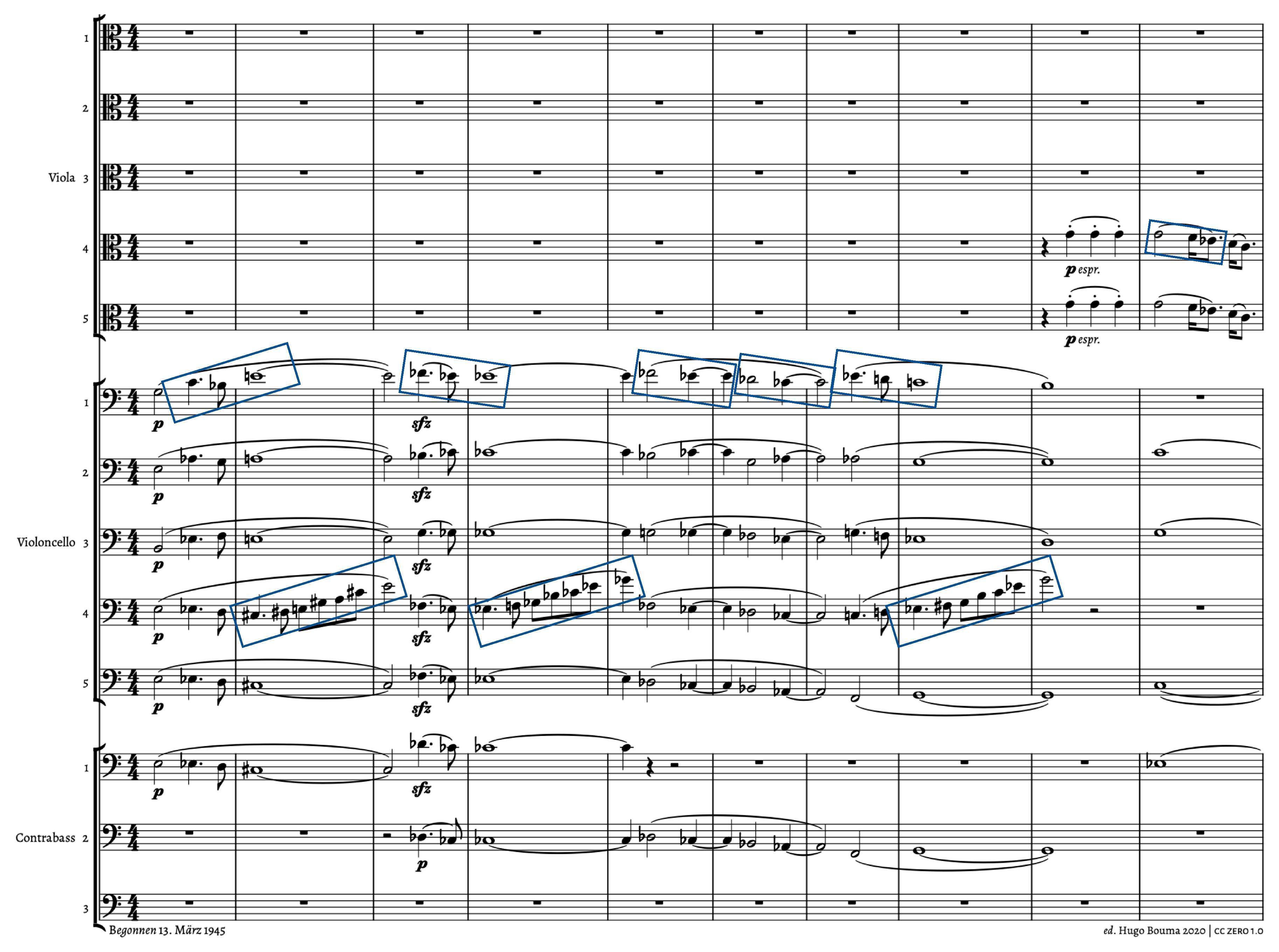

1.1. Back to Basics: Sound Is More than Sound

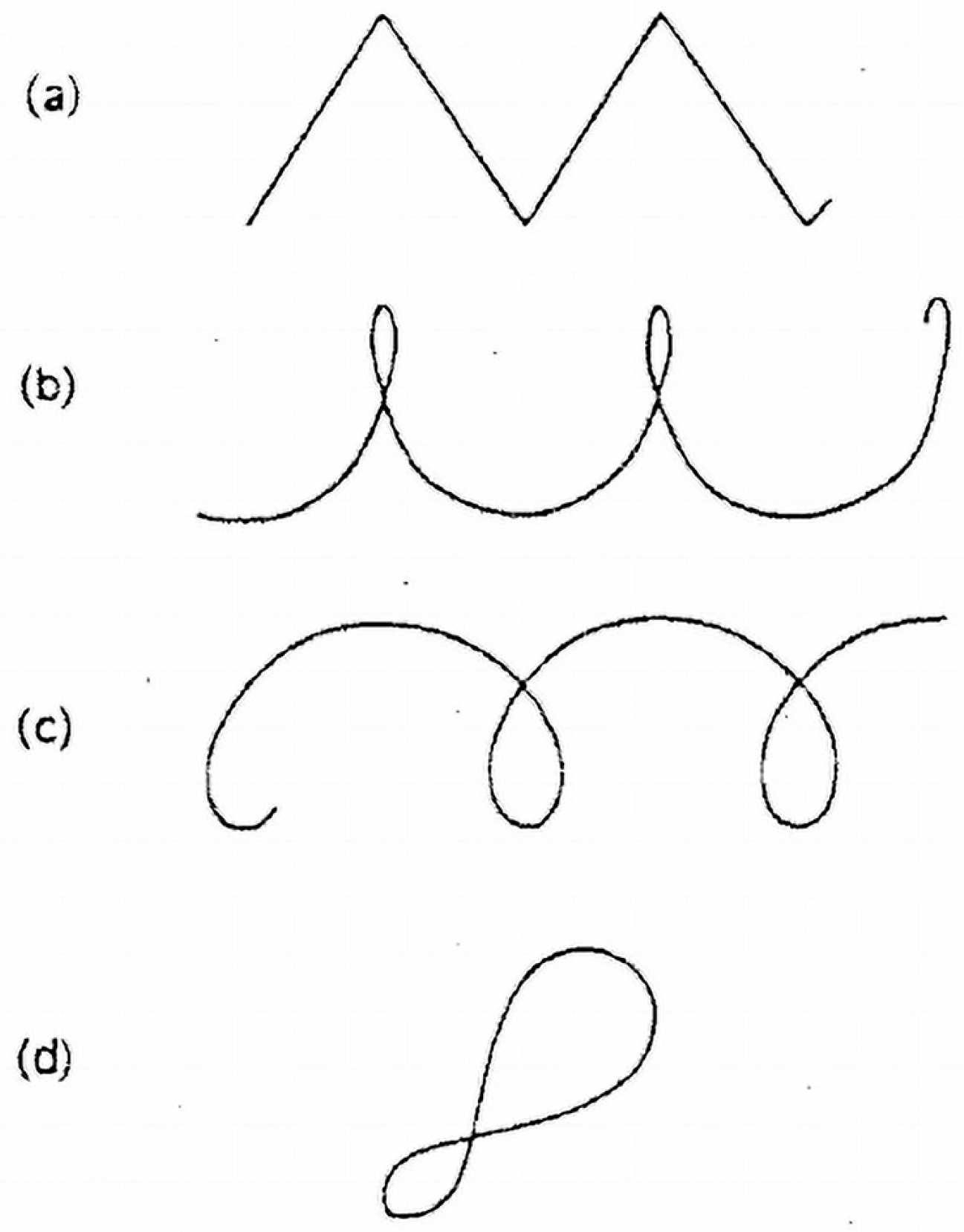

1.2. Music as Movement Through Time

- The expression of the musical experience is not limited to the experience of pure movement; there are even more differentiated expressions that can be expressed by a characteristic movement;

- This differentiated experience is also experienced through the mediation of the acoustic form of this movement;

- The special form of movement forms the bridge from the performer to the listener;

- Just as movement is not only a means of expression but also an essential part of emotional movement, movement in music is not just a means of creation but above all its most fundamental component (Truslit, 1938, p. 51).

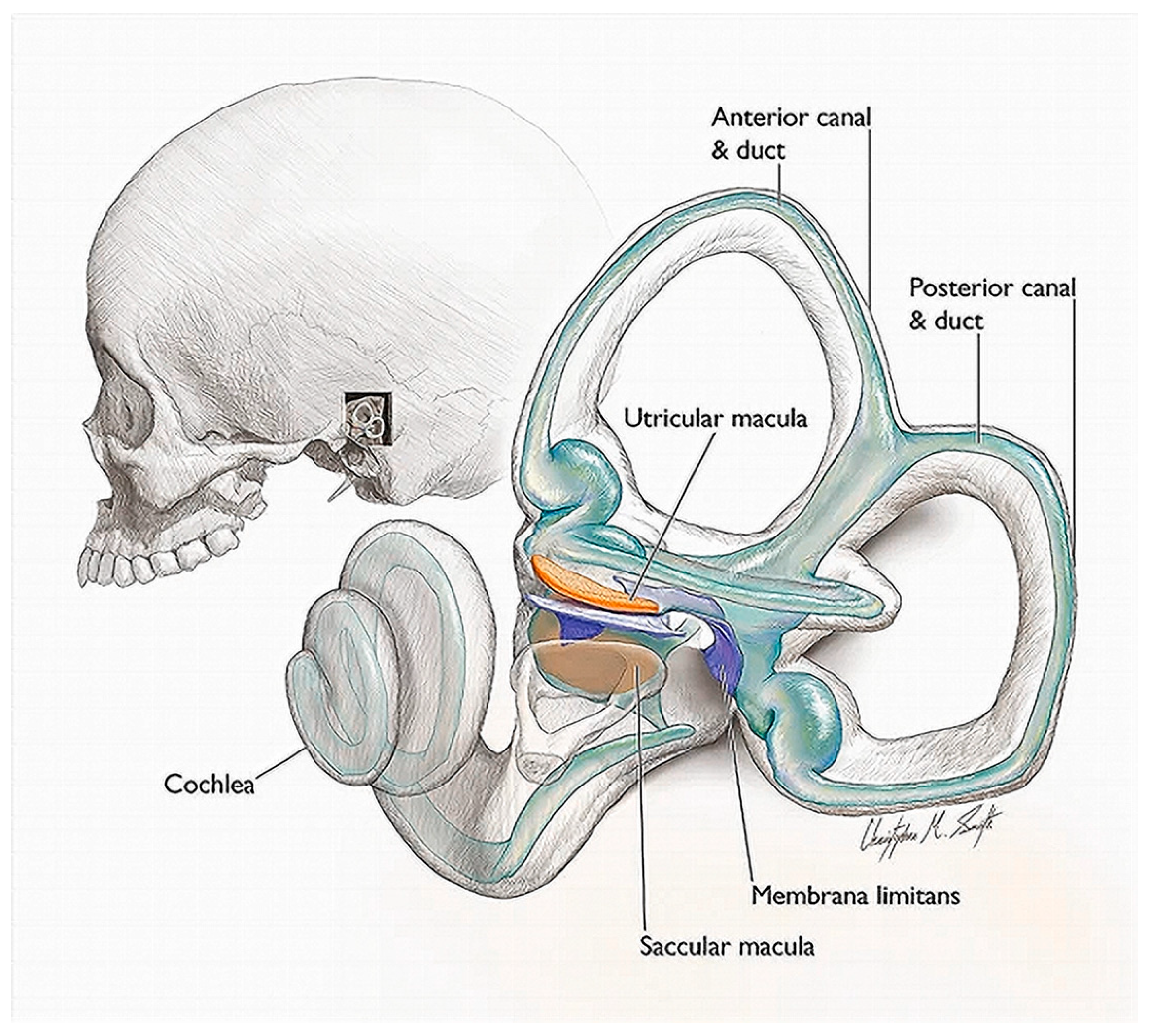

1.3. More on the Vestibular–Motor Coupling and Acoustic Stimulation

2. Music as Inner and Outer Motion: Moving and Being Moved

2.1. Music as Fluidum: Rheology and the Study of Matter That Flows

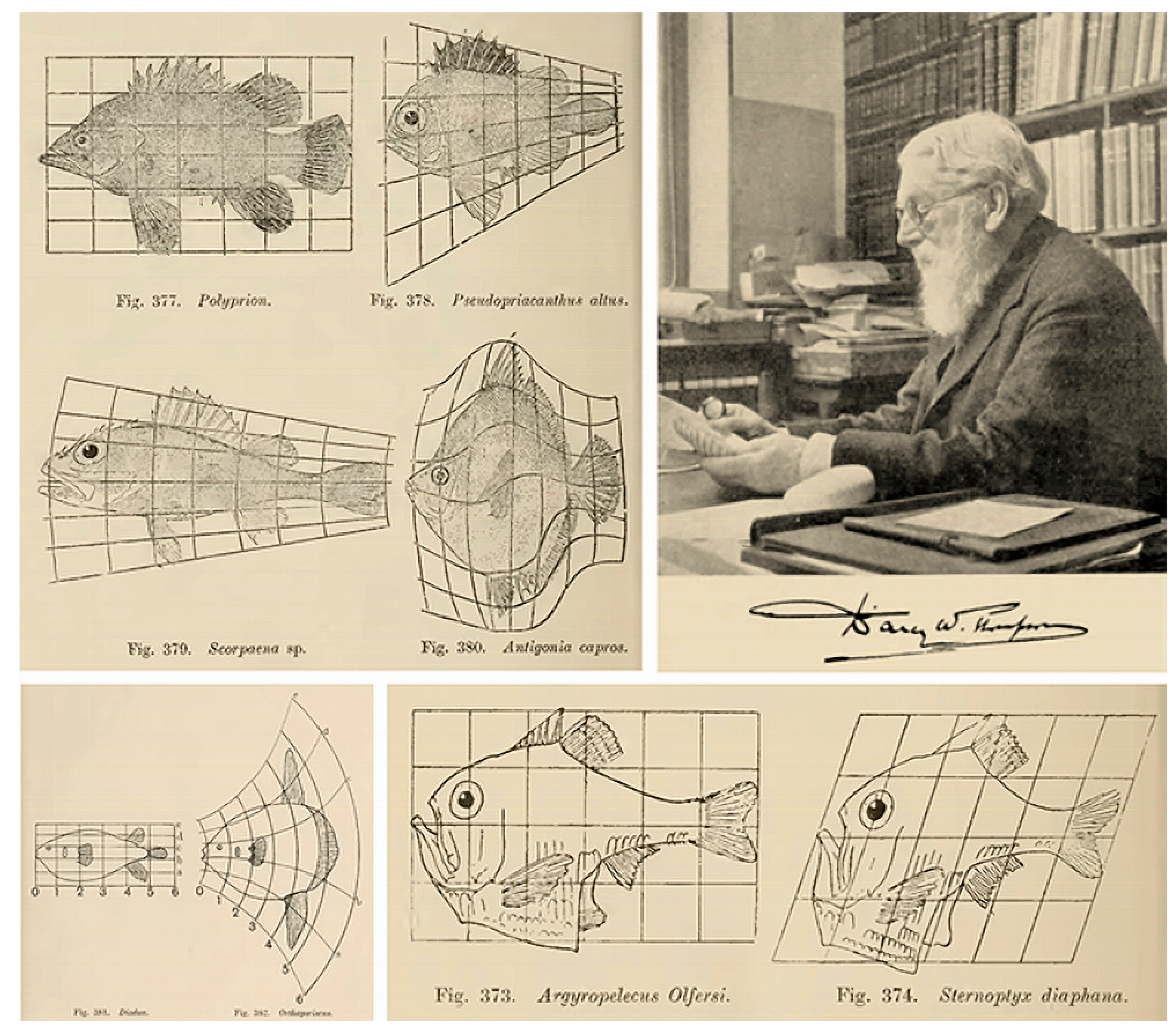

2.2. From Flux to Continuity: Music as an Organism

2.3. The Concept of Organic Form and the Notion of Process

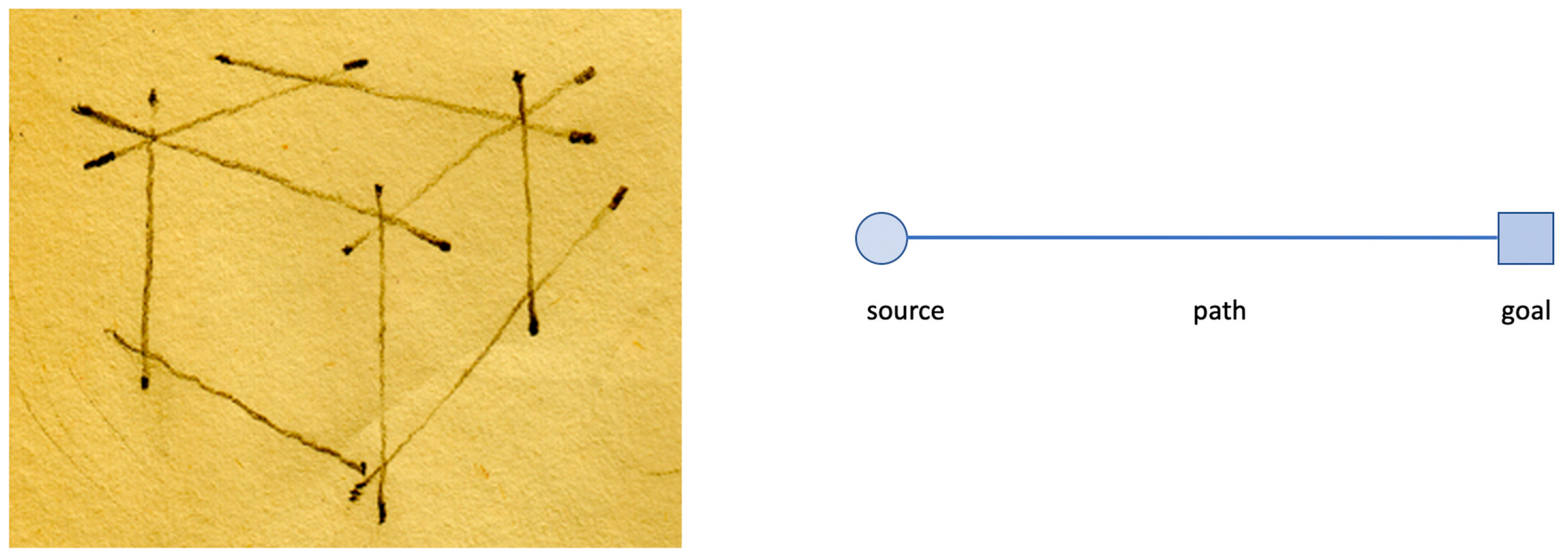

2.4. Phoronomy and the Genetic Definition of Geometric Figures

2.5. Sensorimotor Integration and Ideomotor Simulation

3. Dynamics of Listening

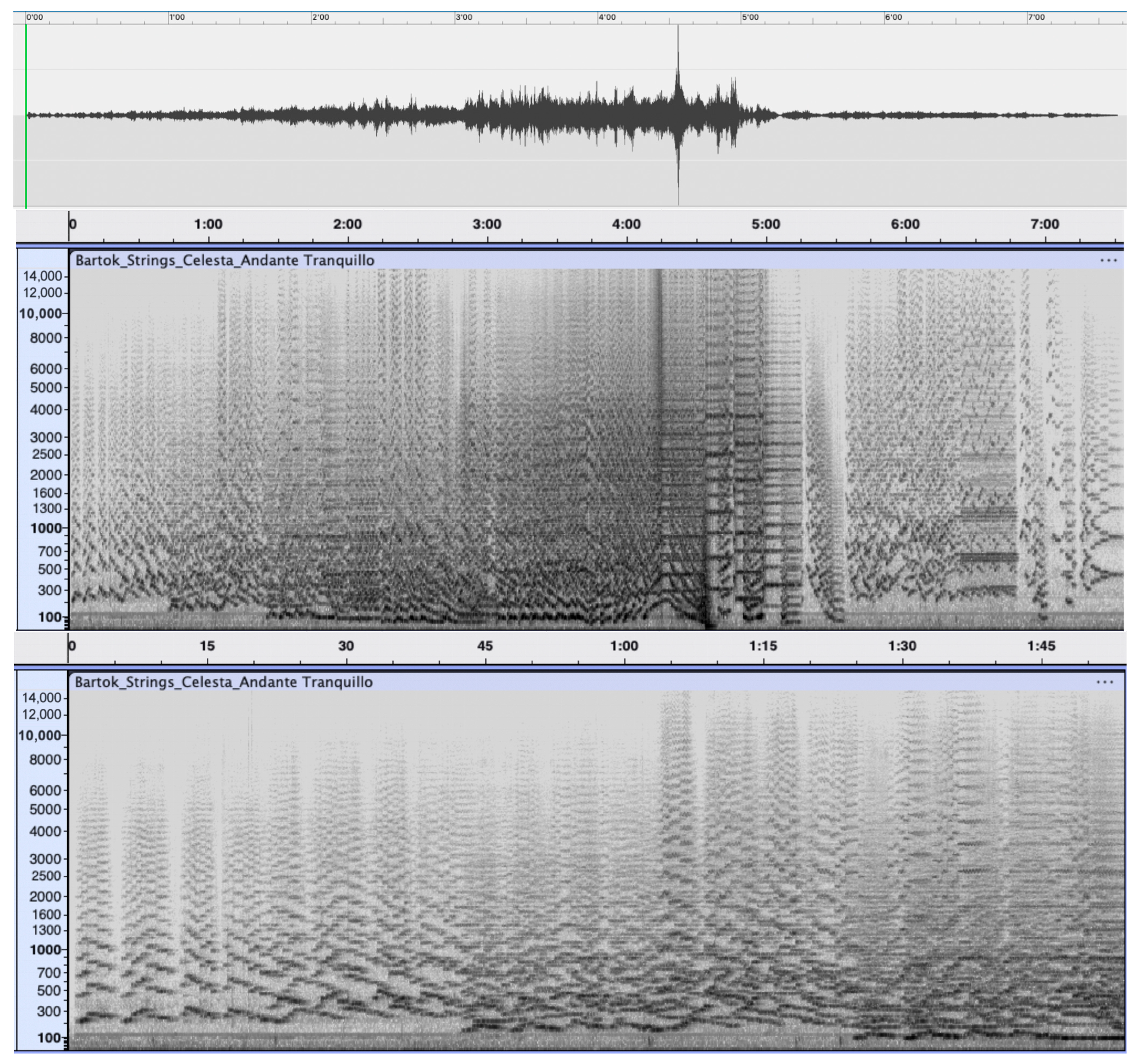

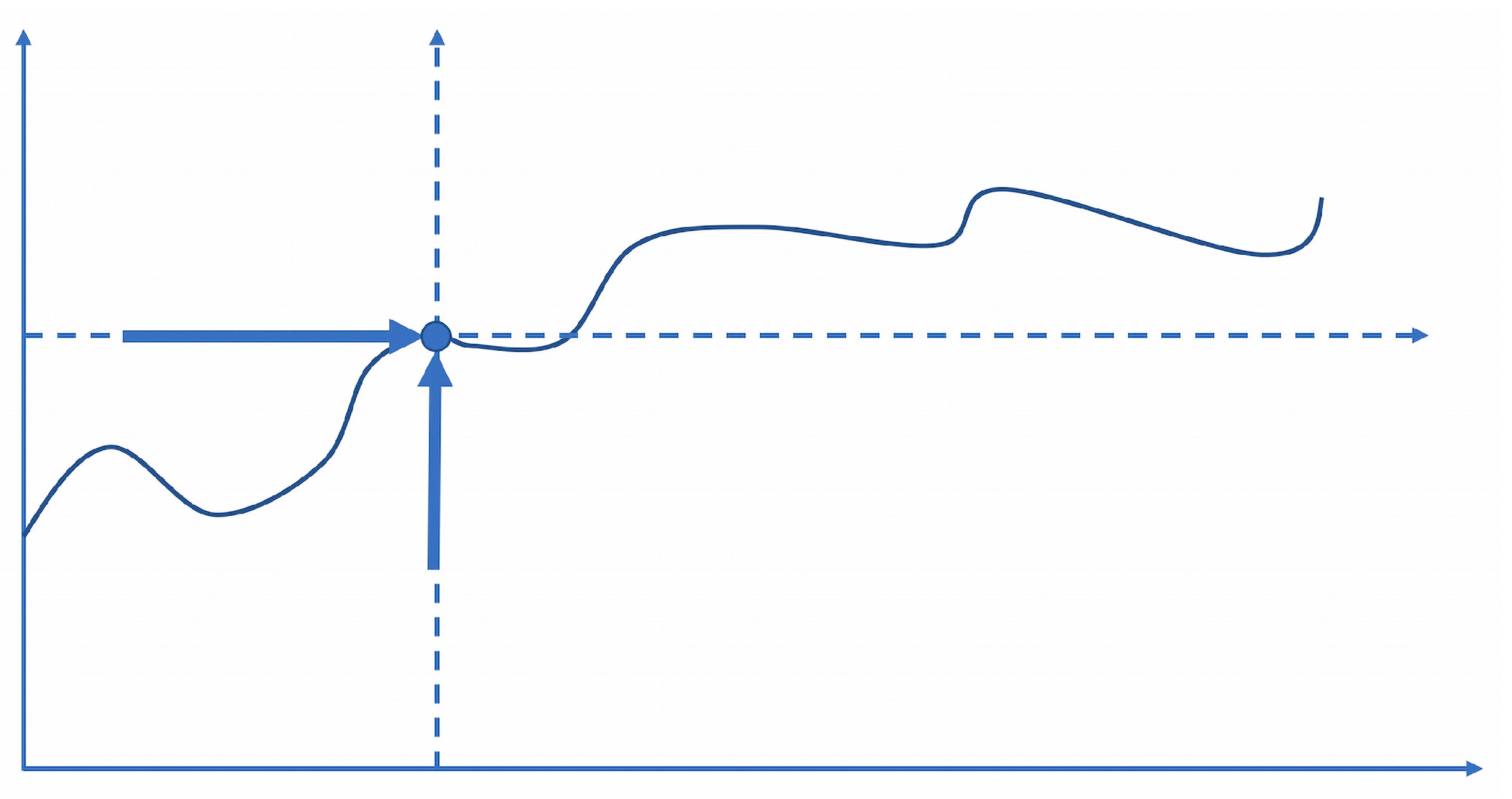

3.1. Music as a Continuous Function of Time

3.2. Sound Tracking and the Consumption of Time

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

- Can all music be conceived as flowing energy? What about percussive sounds and music with an abundance of beats? Is it possible to generalize from music that typically flows organically to other kinds of music?

- What is the relationship between rheological and phenomenological listening?

- How discrete is discrete? Zooming in on the sonorous unfolding shows a transition from a point in time to an event with some temporal unfolding (Δt). The momentary then takes on a rheological signature.

- Is it possible to refine the process of listening by learning to listen as if we listen in slow motion to the actual unfolding? Is this the hallmark of expert listeners and/or top performers? Is this related to the time frame of perception, and is it possible to modify this frame through training and attentional focus? (see for example, Rammsayer & Altenmüller, 2006; Kraus & Chandrasekaran, 2010).

- High-resolution listening is rheological listening. It increases the number of perceived sounding elements to such an extent that the discrete elements transform into a continuous flux.

- How can we translate the flow of sounding events in rheological terms? How can we provide a quantitative description of the sounding flux? Potential parameters are speed, volume, flow, acceleration, resistance, viscosity, elasticity, etc. How can we translate these physical parameters to the realm of music without losing the rigor of scientific definitions?

- Can the river metaphor be operationalized in terms of morphodynamics or hydrodynamics as applied to music as a sounding flux?

- The existing research on beat induction and entrainment should be broadened to encompass also non-rhythmic and non-metric music, even including natural and artificial sounds.

- What is the impact of defining music as vibration in the vestibular response? Does vestibular activation also occur at low levels of sound intensity? Can we conceive of vestibular responses in cases of mere listening without manifest motor behavior?

- How to refine the measurement of the vestibular responses, both in a direct and indirect way. What are future perspectives on using cochlear and vestibular myogenic responses?

- To what extent is the vestibular response able to modulate the sensory input and alter the aesthetic response by the listener? What is the functional significance of the efferent vestibular system compared to the cochlear responses of the inner ear?

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnheim, R. (1969). Visual thinking. Faber and Faber Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, D., & Hallpike, C. (1934). On the function of the saccule. Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 49, 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Assafjew, B. (1976). Die musikalische Form als Prozeß. Neue Musik. [Google Scholar]

- Attneave, F. (1972). The representation of physical space. In A. Melton, & E. Martin (Eds.), Coding processes in human memory (pp. 283–306). Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Attneave, F., & Olson, R. (1971). Pitch as a medium: A new approach to psychophysical scaling. The American Journal of Psychology, 84(2), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baber, C. (2021). Embodying design: An applied science of radical embodied cognition. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Badler, N. (1986). Motion graphics, description and control. In N. Badler, & J. Tsotsos (Eds.), Motion: Representation and Perception, Proceedings of the ACM S/GGRAPH/SIGART. Interdisciplinary workshop on motion: Representation and perception, Toronto, Canada, 1983 (pp. 295–302). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Baggs, E., & Chemero, A. (2021). Radical embodiment in two directions. Synthese, 198(Suppl. 9), 2175–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L. (1999). Perceptual symbols systems. Behaviorial & Brain Sciences, 22, 577–660. [Google Scholar]

- Batstone, P. (1969). Musical Analysis as Phenomenology. Perspectives in New Music, 7(2), 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becking, G. (1928). Der Musikalische Rhythmus als Erkenntnisquelle. Filser. [Google Scholar]

- Bergé, P. (2009). Musical form, forms, formenlehre. Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz, A. (1996). The role of inhibition in the hierarchical gating of executed and imagined movements. Cognitive Brain Research, 3, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthoz, A. (1997). Le sens du movement. Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Bickford, R., Jacobson, J., & Cody, D. (1964). Nature of average evoked potentials to sound and other stimuli in man. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 112, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, E. (1922). Fluidity and plasticity. McGraw-Hill Book Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, E. (1944). The history of the society of rheology from 1924–1944. Available online: https://www.rheology.org/sor/History/Bingham-History_of_SoR_1924-1944.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Bonini, L., Rotunno, C., Arcuri, E., & Gallese, V. (2022). Mirror neurons 30 years later: Implications and applications. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulez, P., Changeux, J.-P., & Manoury, P. (2019). Enchanted neurons. The brain and music. Editions Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Brelet, G. (1949). Le temps musical. Essai d’une esthétique nouvelle de la musique. PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Brelet, G. (1968). L’esthétique du discontinu dans la musique nouvelle. Revue d’Esthétique, 2-3-4, 253–277. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, E. (2013). Music after Deleuze. Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Caplin, W. (2009). What are formal functions? In P. Bergé (Ed.), Musical form, forms, formenlehre (pp. 19–68). Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassirer, E. (1977). Philosophie der symbolischen Formen. Erster teil. Die Sprache. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. (Original work published 1922). [Google Scholar]

- Chemero, T. (2009). Radical embodied cognitive science. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli, L., & Trehub, S. (2019). Dancing to Metallica and Dora: Case study of a 19-month-old. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, M., Sager, R., & Will, U. (2005). In time with the music: The concept of entrainment and its significance for ethnomusicology. European Meetings in Ethnomusicology, 11, 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, T. (1975). Some comparisons between intuitive and scientific descriptions of music. Journal of Music Theory, 19(1), 66–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T. (1983). Music as heard: A study in applied phenomenology. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clynes, M. (1977). Sentics: The touch of emotions. Doubleday Anchor. [Google Scholar]

- Clynes, M. (1983). Expressive microstructure in music, linked to living qualities. In J. Sundberg (Ed.), Studies of music performance (pp. 76–181). Royal Swedish Academy of Music. [Google Scholar]

- Clynes, M. (1986). Music beyond the score. Communication & Cognition, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Clynes, M., & Nettheim, N. (1982). The living quality of music: Neurobiologic patterns of communicating feeling. In M. Clynes (Ed.), Music, mind, and brain: The neuropsychology of music (pp. 47–82). Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, W. (1972). Music and meaning. A theoretical introduction to musical aesthetics. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch, J., Halmagyi, G., & Skuse, N. (1994). Myogenic potentials generated by a click-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 57, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleridge, S. (1914). Shakspeare, a poet generally. In E. E. Rhys (Ed.), Everyman’s library. Coleridge’s essays & lectures on Shakspeare & some other old poets & dramatists (pp. 38–47). Dent & Sons; Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Colerus, E. (1935). Vom Punkt zur vierten Dimension. Geometrie für Jedermann. Paul Zsolnay Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Comte, A. (1998). Cours de philosophie positive; I leçons 1 à 45. Hermann. (Original work published 1830–1842). [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, F. (2013). Towards an enactive account of action: Speaking and joint speaking as exemplary domains. Adaptive Behavior, 21(3), 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins-Sebree, S., Riley, M., & Shockley, K. (Eds.). (2007). Studies in perception and action IX. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Curthoys, I., Grant, J., Pastras, C., Fröhlich, L., & Brown, D. (2021). Similarities and differences between vestibular and cochlear systems—A review of clinical and physiological evidence. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15, 695179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutting, J. (1986). Perceiving and recovering structure from events. In N. Sadler, & J. Tsotsos (Eds.), Motion: Representation and perception, Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH!SIGART interdisciplinary workshop on motion: Representation and perception, Toronto, Canada, 1983 (pp. 264–270). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlhaus, C. (1982). Grundlagen der Musikgeschichte. Laaber-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Danuser, H. (1986–1987). “Energie” als musiktheoretische Kategorie bei Ernst Kurth und Boris Assafjew. Schweitzer Jahrbuch für Musikwissenschaft, 6–7, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy Thompson, W. (1942). On growth and form. Vol. I and II. Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1917). [Google Scholar]

- Defrise, P. (n.d.). Visages de la mathématique. Office de publicité. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2004). A thousand plateaus. Capitalism and schizophrenia. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, A., de Souza, L., Daniel, C., de Oliveira, P., & Pereira, L. (2022). Vestibular system electrophysiology: An analysis of the relationship between hearing and movement. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, 26(2), e272–e277. [Google Scholar]

- de Sélincourt, B. (1920). Music and duration. Music and Letters, 1, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1958). Art as experience. Capricorn Books. (Original work published 1934). [Google Scholar]

- Doraiswamy, D. (2002). The origins of rheology: A short historical excursion. Available online: https://pages.mtu.edu/~fmorriso/cm4650/HistoryOfRheology.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Engel, A. (2010). Directive minds: How dynamics shapes cognition. In J. Stewart, O. Gapenne, & E. Di Paolo (Eds.), Enaction. Toward a new paradigm for cognitive science (pp. 219–243). The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A., Maye, A., Kurthen, M., & König, P. (2013). Where’s the action? The pragmatic turn in cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(5), 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. (1990). Listening to Music. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fatone, G., Clayton, M., & Leante, L. (2011). Imagery, melody and gesture in cross-cultural perspective. In A. Gritten, & E. King (Eds.), New perspectives on music and gesture (pp. 203–220). Ashgate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, J., Epstein, D., & Richards, W. (1992). Force dynamics of tempo change in music. Music Perception, 10, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, L. (1984). Phenomenology as a tool for music analysis. The Musical Quarterly, 70(3), 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. (2013). Kant’s construction of nature: A reading of the metaphysical foundations of natural science. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson, A. (1986). Rhythm in music. In J. Evans, & M. Clynes (Eds.), Rhythm in psychological, linguistic and musical processes (pp. 131–167). Charles C. Thomas. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson, A. (1988). Timing in music performance and its relations to music experience. In J. Sloboda (Ed.), Generative processes in music (pp. 27–51). Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galantucci, B., Fowler, C., & Turvey, M. (2006). The motor theory of speech perception reviewed. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 13(3), 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S., & Zahavi, D. (2008). The phenomenological mind. An introduction to philosophy of mind and cognitive science. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gallese, V., Eagle, M., & Migone, P. (2007). Intentional attunement: Mirror neurons and the neural underpinnings of interpersonal relations. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55, 131–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallese, V., & Goldman, A. (1998). Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mind-reading. Trends in Cognitive Science, 2(2), 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerry, D., Faux, A., & Trainor, L. (2010). Effects of Kindermusik training on infants’ rhythmic enculturation. Developmental Science, 13(3), 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godøy, R. I. (1997). Formalization and epistemology. Scandinavian University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. (1982). Temporal processes in Beethoven’s music. Gordon and Breach. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, T. (1984). Listening as intuiting: A critique of Clifton’s theory of intuitive description. In Theory Only, 7(8), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Valiente, J.-J. (2024). Compositional rheology: Drafting musical flux through fluid mechanics and drawing. Leonardo, 57(5), 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldbrandsen, E. (2015). Playing with transformations: Boulez’s Improvisation III sur Mallarmé. In E. Guldbrandsen, & J. Johnson (Eds.), Transformations of musical modernism (pp. 223–244). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guldbrandsen, E. (2020). Om den psykologiske realiteten av langstrakt musikalsk form: Et musikkfilosofisk forsøk. In Ø. Varkøy, & H. Holm (Eds.), Musikkfilosofiske tekster. Tanker om musikk—Og sprak språk, tolkning, erfaring, tid, klang, stillhet (pp. 191–214). Cappelen Damm Akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Hanslick, E. (1966). Vom musikalisch-Schönen. Breitkopf & Härtel. (Original work published 1854). [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, N. (1953). Ästhetik. de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, G., Friedrich, V., & Martinelli, G. (2014). Projection neurons of the vestibulo-sympathetic reflex pathway. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 522, 2053–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holstein, G., Friedrich, V., & Martinelli, G. (2016). Glutamate and GABA in Vestibulo-sympathetic pathway neurons. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husserl, E. (1950). Cartesianische Meditationen und Pariser Vorträge, Husserliana I. Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (D. Carr, Trans.). Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, D., & Myin, E. (2013). Radicalizing enactivism. Basic minds without content. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ihde, D. (2007). Listening and voice: Phenomenologies of sound. Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, R. (1987). Consciousness and the computational mind. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janmey, P., & Schliwa, M. (2008). Rheology. Current Biology, 18(15), R639–R640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannerod, M. (1994). The representing brain: Neural correlates of motor intention and imagery. Behavioural Brain Sciences, 17, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannerod, M. (1995). Mental imagery in the motor context. Neuropsychologia, 33(11), 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. (2007). The meaning of the body. Aesthetics of human understanding. The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. (1987). Perspectives on musical times. In A. Gabrielson (Ed.), Action and perception in rhythm and music (pp. 153–175.). Royal Swedish Academy of Music. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. (2019). Time will tell: A theory of dynamic attending. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M., & Boltz, M. (1989). Dynamic attending and responding to time. Psychological Review, 96, 459–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T. (1992). Vestibular short latency responses to pulsed linear acceleration in unanesthetized animals. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 82, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, T., & Jones, S. (1999). Short latency compound action potentials from mammalian gravity receptor organs. Hearing Research, 136, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, I. (1900). Metaphysischen Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaft. Kants gesammelte Schriften, Band 4. Königlich Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften. (Original work published 1786). [Google Scholar]

- Kofi Agawu, V. (1991). Playing with signs: A semiotic interpretation of classic music. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, N., & Chandrasekaran, B. (2010). Music training for the development of auditory skills. Nature Reviews/Neuroscience, 11, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, W. (1998). Innere Dynamik und Energetik in Ernst Kurths Musiktheorie. Voraussetzungen, Grundzüge, analytische Perspektiven. Hans Schneider. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, E. (1925). Bruckner (2 vols). Hesse. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, E. (1931). Musikpsychologie. Max Hesses Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortonyi (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (pp. 202–251). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux, J. (2002). Synaptic self: How our brains become who we are. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, D. (1986). Music theory, phenomenology, and modes of perception. Music Perception, 3(4), 327–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. (1952). Constructs in field theory. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Field theory in social science. Selected theoretical papers by Kurt Lewin. Tavistock Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, A., Cooper, F., Shankweiler, D., & Studdert-Kennedy, M. (1967). Perception of speech code. Psychological Review, 74, 431–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, A., & Mattingly, I. (1985). The motor theory of speech perception revised. Cognition, 21, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochhead, J. (1980). Some musical applications of phenomenology. Indiana Theory Review, III(3), 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead, J. (1986). Phenomenological approaches to the analysis of music: Report from Binghamton. Theory and Practice, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Malkin, A., & Isayev, A. (2005). Rheology. Conceps, methods, and applications. ChemTec Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, M. A., Murray, A., Wijesinghe, R., Cullen, K., Tung, V. W., & Camp, A. J. (2015). Efferent vestibular neurons show homogenous discharge output but heterogeneous synaptic input profile in vitro. PLoS ONE, 10, e0139548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzola, M., & Andreatta, M. (2007). Diagrams, gestures and formulae in music. Journal of Mathematics and Music, 1(1), 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Määttänen, P. (2000). Aesthetic experience: A problem in Praxialism. Finnish Journal of Music Education, 5(1–2), 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Meelberg, V. (2021). Thinking/feeling musical narrative. In I. Khannanov, & R. Ruditsa (Eds.), Proceedings of the worldwide music conference 2021 (Vol. 2, pp. 29–40). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mersmann, H. (1926). Angewandte Musikästhetik. Max Hesses Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Metts, B., Kaufman, G., & Perachio, A. (2006). Polysynaptic inputs to vestibular efferent neurons as revealed by viral transneuronal tracing. Experimental Brain Research, 172, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L. (1961). Emotion and meaning in music. University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1956). [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, L. (1973). Explaining music. Essays and explorations. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, C. (1795). Ueber den Geist der Tonkunst mit Rücksicht auf Kants Kritik der ästhetischen Urteilskraft. Schäftrischen Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, C. (1801). Einige Ideen über die ästhetische Natur der Tonkunst. Eunomia. Eine Zeitschrift des 19. Jahrhunderts, I, 254–260, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar-Szakacs, I., & Overy, K. (2006). Music and mirror neurons: From motion to “e”motion. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1(3), 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmour, E. (1990). The analysis and cogniton of basic melodic structures: The implication-realization model. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan, J., & Noë, A. (2001a). A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 939–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, J., & Noë, A. (2001b). What is it like to see: A sensorimotor theory of perceptual experience. Synthese, 129(1), 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, N. (1986). La forme musicale comme processus. IRASM, 17(2), 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overy, K., & Molnar-Szakacs, I. (2009). Being together in time: Musical experience and the mirror neuron system. Music Perception, 26(5), 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillard, J. (1977). La machine organisée et la machine organisante. Revue de L’éducation Physique Belge, 27, 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Paillard, J. (1990). Réactif et Prédictif: Deux modes de gestion de la motricité. In V. Nougier, & J.-P. Bianqui (Eds.), Pratiques sportives et modélisation du geste (pp. 13–56). Université Joseph-Fourier. [Google Scholar]

- Paillard, J. (1994). L’intégration sensori-motrice et idéo-motrice. In M. Richelle, J. Requin, & M. Robert (Eds.), Traité de psychologie expérimentale. 1 (pp. 925–961). Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Parkany, S. (1988). Kurth’s “Bruckner” and the adagio of the seventh symphony. 19th-Century Music, 11(3), 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidou, S. (2022). Effort inference and prediction by acoustic and movement descriptors in interactions with imaginary objects during Dhrupad vocal improvisation. Wearable Technology, 3, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastras, C., Curthoys, I., & Brown, D. (2017). In vivo recording of the vestibular microphonic in mammals. Hearing Research 354, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastras, C., Stefani, S., Camp, A., Curthoys, I., & Brown, D. (2021). Summating potentials from the utricular macula of anaesthetised guinea pigs. Hearing Research, 406, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitot-Cocorda, J. (1985). Morphogenèse du Sens. I. Pour un schématisme de Ia Structure. PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Silver, J., & Trainor, L. J. (2005). Feeling the beat: Movement influences infant rhythm perception. Science, 308, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips-Silver, J., & Trainor, L. J. (2007). Hearing what the body feels: Auditory encoding of rhythmic movement. Cognition, 105, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct. Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, W., & Bridgeman, B. (1996). Handbook of perception and action. Volume 1: Perception. Academic Press, Harcourt Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, W., & Chater, N. (2005). An ideomotor approach to imitation. In S. Hurley (Ed.), Perspectives on imitation: From neuroscience to social science. Vol.1: Mechanisms of imitation and imitation in animals (pp. 141–156). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rammsayer, T., & Altenmüller, E. (2006). Temporal information processing in musicians and nonmusicians. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 24(1), 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, M. (1964). The Deborah number. Physics Today, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, B. H. (1992a). A constraint on the expressive timing of a melodic gesture: Evidence from performance and aesthetic judgment. Music Perception, 10, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, B. H. (1992b). Music as motion: A synopsis of Alexander Truslit’s (1938) “Gestaltung und Bewegung in der Musik” (pp. 265–278). Haskins Laboratories Status Report on Speech Research. SR111/112. [Google Scholar]

- Reti, R. (1961). The thematic process in music. Faber & Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. (2001). Musical imagery between sensory processing and ideomotor simulation. In R. I. Godøy, & H. Jörgensen (Eds.), Musical Imagery (pp. 117–136). Swets & Zeitlinger. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. (2014). Musical sense-making between experience and conceptualisation: The legacy of Peirce, Dewey and James. Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology, 14, 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. (2019). Experience as cognition: Musical sense-making and the ‘in-time/outside-of-time’ dichotomy. Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology, 19, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M. (2021). Musical sense-making. Enaction, experience, and computation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. (2023). A dynamic interactive approach to music listening: The role of entrainment, attunement and resonance. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M., & Eerola, T. (2017). Music and its inductive power: A psychobiological and evolutionary approach to musical emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggle, M. (2009). A simple explanation for vestibular influence on beat perception: No specialized unit needed. Empirical Musicology Review, 4, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G., & Arbib, M. (1998). Language within our grasp. Trends in Neurosciences, 21, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosengren, S., & Colebatch, J. (2018). The contributions of vestibular evoked myogenic potentials and acoustic vestibular stimulation to our understanding of the vestibular system. Frontiers in Neurology, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothfarb, L. (1988). Ernst Kurth as theorist and analyst. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer, E. (1984). Motor theories of cognitive structure: A historical review. In W. Prinz, & A. Sanders (Eds.), Cognition and motor processes. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavio, A., Ryan, K., Moran, N., Van der Schyff, D., & Gallagher, S. (2023). By myself but not alone. Agency, creativity and extended musical historicity. Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 147(2), 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. (1990). Organische Form in der Musik. Stationen eines Begriffs 1795–1850. Bärenreiter. [Google Scholar]

- Schubotz, R. (2007). Prediction of external events with our motor system: Towards a new framework. Trends in Cognitive Science, 11, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubotz, R. I., Friederici, A. D., & von Cramon, D. Y. (2000). Time perception and motor timing: A common cortical and subcortical basis revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, A. (1951). Making music together: A study in social relationship. Social Research, 18(1), 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, A. (1971). Making music together. In Collected works, II (pp. 172–173). Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, A. (1976). Fragments on the phenomenology of music. Music and Man, 2, 5–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruton, R. (1999). The aesthetics of music. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Serafine, M. (1988). Music as cognition. The development of thought in sound. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sessions, R. (1971). The musical experience of composer, performer, listener. Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1950). [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, R. (1981). Psychophysical complementarity. In M. Kubovy, & R. Pomerantz (Eds.), Perceptual organization (pp. 255–341). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, R. (1982a). Geometrical approximations to the structure of musical pitch. Psychological Review, 89(4), 305–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, R. (1982b). Structural representations of musical pitch. In D. Deutsch (Ed.), The psychology of music (pp. 343–390). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheya, A., & Smith, L. B. (2010). Development through sensorimotor coordination. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, E. (1924). Ziele und Wege der Schallanalyse. Zwei Vorträge von E. Sievers. Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Skarda, C. (1979). Alfred Schütz’s phenomenology of music. Journal of Musicological Research, 3(1–2), 75–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smalley, D. (1997). Spectromorphology: Explaining sound-shapes. Organized Sound, 2(2), 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C., Curthoys, I. S., & Laitman, J. (2023). First evidence of the link between internal and external structure of the human inner ear otolith system using 3D morphometric modeling. Scientific Reports, 13, 4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C., Curthoys, I. S., Mukherjee, P., Wong, C., & Laitman, J. (2022). Three-dimensional visualization of the human membranous labyrinth: The membrana limitans and its role in vestibular form. The Anatomical Record, 305, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F. (1976). The experiencing of musical sound: Prelude to a phenomenology of music. Gordon and Breach. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock, A. (2004). On the phenomenology of becoming aware. Continental Philosophy Review, 37, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetson, R. (1905). A motor theory of rhythm and discrete succession. Psychological Review, 12, 250–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoianova, I. (1975). L’énoncé musical. Musique en Jeu, 19, 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stoianova, I. (1976). Narrativisme, téléologie et invariance dans l’œuvre musicale. Musique en Jeu, 25, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, H. (1989). Neural coding of relational invariance in speech: Human language analogs to the barn owl. Psychological Review, 96, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, J. (1932). Is all hearing cochlear? Annals of Otology, Rhinology, & Laryngology, 41, 681–704. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, D. (2017). “As forming becomes form.” Listening, analogizing, and analysis in Kurth’s Bruckner and Musikpsychologie. Journal of Music Theory, 61(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, R. (1972). Stabilité structurelle et morphogénèse. Essai d’une théorie générale des modèles. Benjamin. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, R. (1980). Modèles mathématiques de la morphogénèse. Christian Bourgois. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tichko, P., Kim, J., & Large, E. (2021). Bouncing the network: A dynamical systems model of auditory–vestibular interactions underlying infants’ perception of musical rhythm. Developmental Science, 24, e13103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N. (1992). The dynamics of dynamics: A model of musical expression. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 91, 3540–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N. (1993). Vestibular feedback in music performance. Music Perception, 10, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N. (1994). The auditory primal sketch: A multi-scale model of rhythmic grouping. Journal of New Music Research, 23, 25–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N. (1995). The kinematics of musical expression. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America, 97, 1940–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N. (1999). Motion in music: A neurobiological perspective. Music Perception, 17(1), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N. (2001). Evidence for a behavioral significance of saccular acoustic sensitivity in humans. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N., & Cody, F. (2000). Vestibular responses to loud dance music: A physiological basis of the “rock and roll threshold”? Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 107, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N., Cody, F., & Banks, J. (2000). A saccular origin of frequency tuning in myogenic vestibular evoked potentials?: Implications for human responses to loud sounds. Hearing Research, 141(1–2), 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, N., Lee, C., & O’Boyle, D. (1999). A sensory-motor theory of rhythm, time perception and beat induction. Journal of New Music Research, 28, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, N., & Lee, S. (2015). The sensory-motor theory of rhythm and beat induction 20 years on: A new synthesis and futures perspective. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, J. (2018). On the origins and renaissance of Goethe’s morphology. Herbsttagung «evolving morphology». Elemente der Naturwissenschaft, 108, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, G., & Cody, D. (1971). The averaged inion response evoked by acoustic stimulation: Its relation with the saccule. Annals of Otology, Rhinologye, & Laryngology, 80, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Trainor, L. (2007). Do preferred beat rate and entrainment to the beat have a common origin in movement? Empirical Musicology Review, 2, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, L., Gao, S., Lei, J., Lehtovaara, K., & Harris, L. (2009). The primal role of the vestibular system in determining musical rhythm. Cortex, 45, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, L., & Unrau, A. (2009). Extracting the beat: An experience-dependent complex integration of multisensory information involving multiple levels of the nervous system. Empirical Musicology Review, 4(1), 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truslit, A. (1938). Gestaltung und Bewegung in der Musik. Ein tönendes Buch vom musikalischen Vortrag und seinem bewegungserlebten Gestalten und Hören. Friedrich Vieweg. [Google Scholar]

- Tullio, P. (1929). Das Ohr und die Entstehung der Sprache und Schrift. Urban and Schwarzenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Viviani, P., & Stucchi, N. (1992). Biological movements look uniform. Evidence of motor-perceptual interactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Human Perception and Performance, 18, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory. Foundations, development, applications. Braziller. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, C. (1942). Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature, 150, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddington, C. (1962). The nature of life. Atheneum. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, K. (2010). History of rheology. In P. Lorenzano, H.-J. Rheinberger, E. Ortiz, & C. Delfino Galles (Eds.), History and philosophy of science and technology. Volume III. Encyclopedia of life support systems (pp. 91–106). Eola Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A. (1957). Process and reality. An essay in cosmology. Macmillan. (Original work published 1929). [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H., & Nottebohm, F. (1985). Auditory responses in avian vocal motor neurons: A motor theory for song perception in birds. Science, 229, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. (2018). What is rheology? Eyer, 32, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfram, S. (2018). Are All Fish the Same Shape If You Stretch Them? The Victorian Tale of On Growth and Form. Math Intelligencer, 40, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reybrouck, M. Music as Fluidum: A Rheological Approach to the Materiality of Sound as Movement Through Time. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081118

Reybrouck M. Music as Fluidum: A Rheological Approach to the Materiality of Sound as Movement Through Time. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081118

Chicago/Turabian StyleReybrouck, Mark. 2025. "Music as Fluidum: A Rheological Approach to the Materiality of Sound as Movement Through Time" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081118

APA StyleReybrouck, M. (2025). Music as Fluidum: A Rheological Approach to the Materiality of Sound as Movement Through Time. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081118