The Effectiveness of Compassion Focused Therapy for the Three Flows of Compassion, Self-Criticism, and Shame in Clinical Populations: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Previous Reviews and Current Gaps

1.2. Aims

- The three flows of compassion (self-compassion and interpersonal compassion: compassion from others, and compassion to others);

- Self-criticism;

- Shame (internal and external).

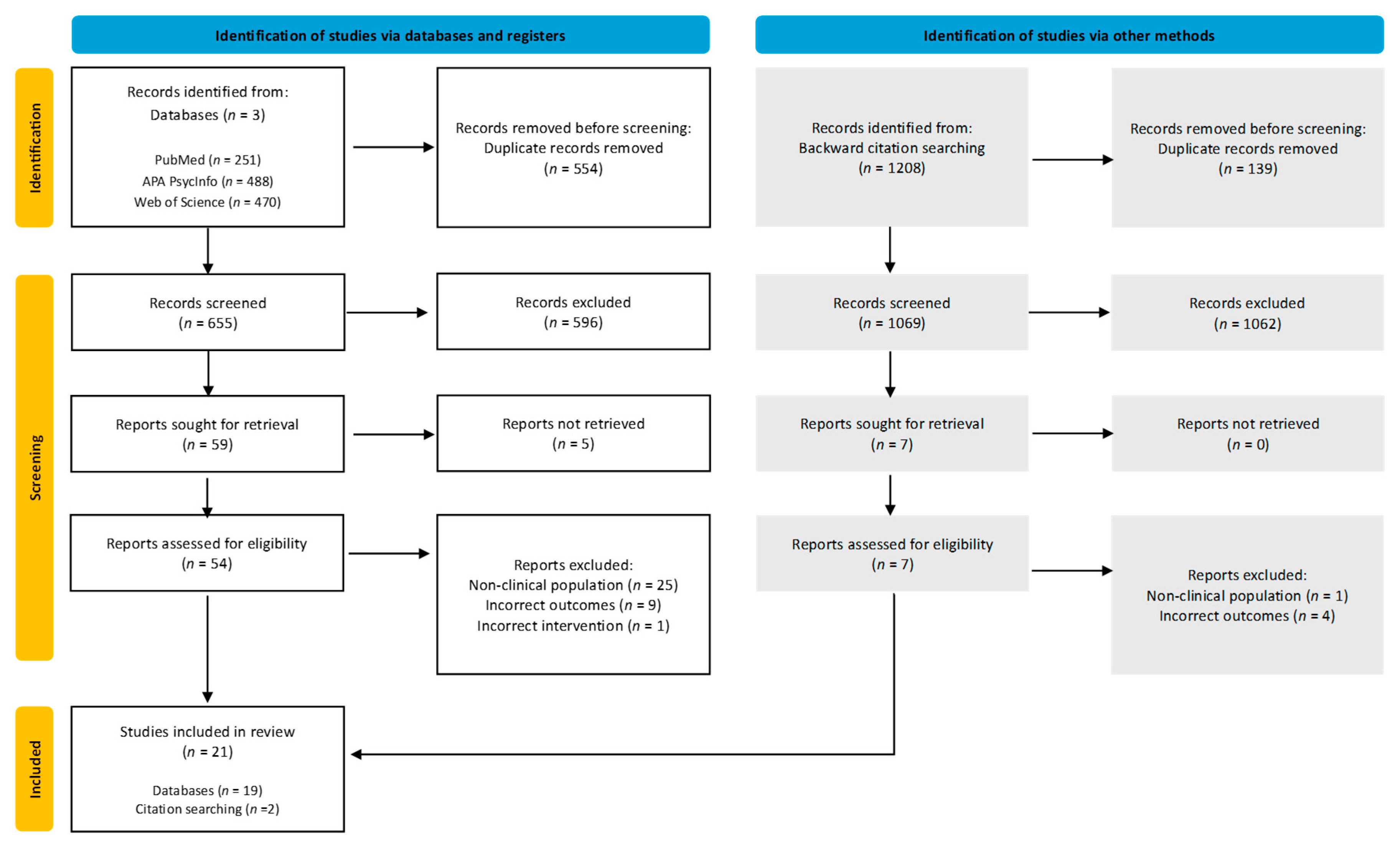

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- -

- Adult clinical populations (≥18 years)

- -

- CFT interventions following Gilbert’s model

- -

- Quantitative measures of compassion flows, self-criticism, or shame

- -

- Any study design except single case studies

- -

- Published and unpublished studies to reduce publication bias

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Intervention Characteristics

3.3. Quality Appraisal

3.3.1. Risk of Bias Within Studies

3.3.2. Risk of Bias Across Studies

3.4. Results Overview

3.4.1. Primary Outcomes

Compassion Flows

Self-Criticism

Shame

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary Findings

4.2. Appraisal of Included Evidence

4.3. Appraisal of Review Processes

4.4. Implications

4.4.1. Practice

4.4.2. Research

4.4.3. Policy

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altavilla, A., & Strudwick, A. (2022). Age inclusive compassion-focused therapy: A Pilot group evaluation. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 15, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo, S., Stiles, C. R., Hagen, N. A., Biondo, P. D., & Cummings, G. G. (2010). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arntz, A., van den Hoorn, M., Cornelis, J., Verheul, R., van den Bosch, W. M. C., & de Bie, A. J. H. T. (2003). Reliability and validity of the borderline personality disorder severity index. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K., Tsuchiya, M., Okamoto, Y., Ohtani, T., Sensui, T., Masuyama, A., Isato, A., Shoji, M., Shiraishi, T., Shimizu, E., Irons, C., & Gilbert, P. (2022). Benefits of group compassion-focused therapy for treatment-resistant depression: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(13), 903842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfield, E., Chan, C., & Lee, D. (2021). Building “a compassionate armour”: The journey to develop strength and self-compassion in a group treatment for complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Beck, J. S., & Newman, C. F. (1993). Hopelessness, depression, suicidal ideation, and clinical diagnosis of depression. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 23(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Beckham, G. (2016, February 3). Cohen’s d and hedges’ g excel calculator. GeorgeBeckham.com (original site no longer available). Available online: https://medinterholguin2023.sld.cu/index.php/medintern/2023/paper/downloadSuppFile/33/3 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Behrouzian, F., Boostani, H., Mousavi Asl, E., Sadrizadeh, N., & Nemati Jole Karan, S. (2024). The effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on patients with bipolar disorder, a randomized clinical trial. Galen Medical Journal, 13, e3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, K., Håkanson, A., Salomonsson, E., & Johansson, I. (2015). Compassion focused therapy to counteract shame, self-criticism and isolation. A replicated single case experimental study for individuals with social anxiety. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 45(2), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braehler, C., Harper, J., & Gilbert, P. (2013). Compassion focused group therapy for recovery after psychosis. In C. Steel (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Evidence-based interventions and future directions (pp. 236–266). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Callow, T. J., Moffitt, R. L., & Neumann, D. L. (2021). External shame and its association with depression and anxiety: The moderating role of self-compassion. Australian Psychologist, 56(1), 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapton, N. E., Williams, J., Griffith, G. M., & Jones, R. S. (2018). “Finding the person you really are … on the inside”: Compassion focused therapy for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(2), 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routeledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D. R. (1996). Empirical studies of shame and guilt: The Internalized Shame Scale. In D. L. Nathanson (Ed.), Knowing feeling: Affect, script, and psychotherapy (pp. 132–165). W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J. J., Dinnes, J., D’Amico, R., Sowden, A. J., Sakarovitch, C., Song, F., Petticrew, M., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment, 7(27), 1–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwan, K., Gamble, C., Williamson, P. R., & Kirkham, J. J. (2013). Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias—An updated review. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e66844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, C., Mellor-Clark, J., Margison, F., Barkham, M., Audin, K., Connell, J., & McGrath, G. (2000). CORE: Clinical outcomes in routine evaluation. Journal of Mental Health, 9(3), 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C., Moura-Ramos, M., Matos, M., & Galhardo, A. (2022). A new measure to assess external and internal shame: Development, factor structure and psychometric properties of the external and internal shame scale. Current Psychology, 41(4), 1892–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M. B., & Gibbon, M. (2004). The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID-I) and the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II disorders (SCID-II). In M. J. Hilsenroth, & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment (Vol. 2. Personality assessment, pp. 134–143). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders, clinician version (SCID-CV). American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J., Cattani, K., & Burlingame, G. M. (2021). Compassion focused therapy in a university counseling and psychological services center: A feasibility trial of a new standardized group manual. Psychotherapy Research, 31(4), 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharraee, B., Zahedi Tajrishi, K., Ramezani Farani, A., Bolhari, J., & Farahani, H. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of compassion focused therapy for social anxiety disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 12(4), 80945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 7(3), 174–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2001). Evolution and social anxiety. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(4), 723–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (2015). The evolution and social dynamics of compassion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. (2017). Compassion focused group therapy for college counseling centers. Compassionate Mind Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P. (2020). Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P., Basran, J. K., Raven, J., Gilbert, H., Petrocchi, N., Cheli, S., Rayner, A., Hayes, A., Lucre, K., Minou, P., Giles, D., Byrne, F., Newton, E., & McEwan, K. (2022). Compassion focused group therapy for people with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder: A feasibility study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 841932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., Ceresatto, L., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P., & Choden. (2013). Mindful compassion: Using the power of mindfulness and compassion to transform our lives. Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P., Clark, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N. V., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticising and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2004). A pilot exploration of the use of compassionate images in a group of self-critical people. Memory, 12(4), 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P., Kirby, J., & Petrocchi, N. in press. Compassion focused therapy: Group therapy guidance. Routledge.

- Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P., & Simos, G. (Eds.). (2022). Compassion focused therapy: Clinical practice and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., Hill, C. L., Heninger, G. R., & Charney, D. S. (1989). The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, K., Gilbert, P., & Allan, S. (1994). An exploration of shame measures—I: The other as shamer scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 17(5), 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodin, J., Clark, J. L., Kolts, R., & Lovejoy, T. I. (2019). Compassion focused therapy for anger: A pilot study of a group intervention for veterans with PTSD. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 13, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L. V. (1981). Distribution theory for glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational Statistics, 6(2), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L. V., Pustejovsky, J. E., & Shadish, W. R. (2012). A standardized mean difference effect size for single case designs. Research Synthesis Methods, 3(3), 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriot-Maitland, C., Vidal, J. B., Ball, S., & Irons, C. (2014). A compassionate-focused therapy group approach for acute inpatients: Feasibility, initial pilot outcome data, and recommendations. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, M., Schlander, C., Farver-Vestergaard, I., Lundorff, M., Wellnitz, K. B., Komischke-Konnerup, K. B., & O’Connor, M. (2022). Group-based compassion-focused therapy for prolonged grief symptoms in adults—Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Research, 314, 114683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, L., Cleghorn, A., McEwan, K., & Gilbert, P. (2012). An exploration of group-based compassion focused therapy for a heterogeneous range of clients presenting to a community mental health team. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 5(4), 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J. N., & Gilbert, P. (2019). Commentary regarding Wilson et al. (2018) “Effectiveness of ‘self-compassion’ related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” All is not as it seems. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A Meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolts, R. L. (2015). True strength: A compassion focused therapy approach for working with anger. Available online: https://contextualconsulting.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/True-Strength-Manual-Anger-2016.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laithwaite, H., O’Hanlon, M., Collins, P., Doyle, P., Abraham, L., Porter, S., & Gumley, A. (2009). Recovery after psychosis (RAP): A compassion focused programme for individuals residing in high security settings. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(5), 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, M. J., Gregersen, A. T., & Burlingame, G. M. (2004). The outcome questionnaire-45. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults (3rd ed., pp. 191–234). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, V. A., & Lee, D. (2014). An exploration of people’s experiences of compassion-focused therapy for trauma, using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(6), 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic Benefits of compassion-focused therapy: An Early Systematic Review. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., & James, S. (2012). The Compassionate mind approach to recovering from trauma (1st ed.). Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D., Scragg, P., & Turner, S. (2001). The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: A clinical model of shame-based and guilt-based PTSD. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74(4), 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucre, K. M., & Corten, N. (2013). An exploration of group compassion-focused therapy for personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(4), 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L., Steindl, S. R., & Bambling, M. (2022). Compassion focused group therapy for adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: A preliminary investigation. Mindfulness, 13, 1144–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, J., Tsivos, Z., Woodward, S., Fraser, J., & Hartwell, R. (2018). Compassion focused therapy groups: Evidence from routine clinical practice. Behaviour Change, 35(3), 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, L. A., Wan, M. W., Smith, D. M., & Wittkowski, A. (2023). The effectiveness of compassion focused therapy with clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 326, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naismith, I., Ripoll, K., & Pardo, V. M. (2021). Group compassion-based therapy for female survivors of intimate-partner violence and gender-based violence: A pilot study. Journal of Family Violence, 36, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbala, F., Borjali, A., Ahmadian-Attari, M. M., & Noorbala, A. A. (2013). Effectiveness of compassionate mind training on depression, anxiety, and self-criticism in a group of Iranian depressed patients. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 8(3), 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Otsubo, T., Tanaka, K., Koda, R., Shinoda, J., Sano, N., Tanaka, S., Aoyama, H., Mimura, M., & Kamijima, K. (2005). Reliability and validity of Japanese version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 59(5), 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & McGuinness, L. A. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocchi, N., Cosentino, T., Pellegrini, V., Femia, G., D’Innocenzo, A., & Mancini, F. (2021). Compassion-focused group therapy for treatment-resistant OCD: Initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 594277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, S. M., de Jong, A., Trompetter, H., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Chakhssi, F. (2024). Effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy for self-criticism in patients with personality disorders: A multiple baseline case series study. Personality and Mental Health, 18(1), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pol, S. M., Pots, W. T. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2020). Compassion-focused therapy: Group protocol. University of Twente. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H. G., Horowitz, M. J., Jacobs, S. C., Parkes, C. M., Aslan, M., Goodkin, K., Raphael, B., Marwit, S. J., Wortman, C., Neimeyer, R. A., Bonanno, G., Block, S. D., Kissane, D., Boelen, P., Maercker, A., Litz, B. T., Johnson, J. G., First, M. B., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2009). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine, 6(8), e1000121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogier, G., Muzi, S., Morganti, W., & Pace, C. S. (2023). Self-criticism and attachment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 214, 112359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R. (1994). Science and ethics in conducting, analyzing, and reporting psychological research. Psychological Science, 5(3), 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santor, D. A., Zuroff, D. C., Mongrain, M., & Fielding, A. (1997). Validating the mcgill revision of the depressive experiences questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69(1), 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, Y., Mohagheghi, H., & Petrocchi, N. (2021). A preliminary investigation on the effectiveness of compassionate mind training for students with major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 12, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessions, L., Pipkin, A., Smith, A., & Shearn, C. (2023). Compassion and gender diversity: Evaluation of an online compassion-focused therapy group in a gender service. Psychology & Sexuality, 14(3), 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, J., & Griffiths, C. (2021). An evaluation of compassion-focused therapy within adult mental health inpatient settings. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(3), 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B. H., Ciliska, D., Dobbins, M., & Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(3), 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). The levels of self-criticism scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderheiden, E., & Mayer, C. H. (Eds.). (2024). Gender-specific facets of shame: Exploring a resource within and between cultures. In Shame and gender in transcultural contexts. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakelin, K. E., Perman, G., & Simonds, L. M. (2021). Effectiveness of self-compassion related interventions for reducing self-criticism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W., Marx, B. P., Friedman, M. J., & Schnurr, P. P. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in DSM-5: New criteria, new measures, and implications for assessment. Psychological Injury and Law, 7(2), 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The impact of event scale—Revised. In J. P. Wilson, & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 399–411). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welford, M. (2012). The compassionate mind approach to building your self-confidence using compassion focused therapy. Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A. C., Mackintosh, K., Power, K., & Chan, S. W. Y. (2018). Effectiveness of self-compassion related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10(6), 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICOS | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

| Non-clinical populations. This includes

|

| Intervention | Group or individual CFT derived from Paul Gilbert (2009, 2014, 2020), including psychoeducation (for example, the tricky brain, three regulatory systems, fear of compassion, and the role of shame and self-criticism) and exercises (for example, soothing rhythm breathing, mindful attention, and compassionate letter writing and/or imagery). | Any other interventions that do not constitute as CFT or do not cover the key components of the model, including other compassion-based interventions (for example, Neff’s mindful self-compassion, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and compassion cultivation training). |

| Comparison |

| |

| Outcome | Pre- and post-intervention outcomes for:

|

|

| Study Design |

|

|

| Effectiveness | Very Small | Small | Medium | Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988) | <0.20 | 0.20 | 0.50 | ≥0.80 |

| Hedges’ g (Cohen, 1988) | 0.20 | 0.50 | ≥0.80 | |

| Rosenthal’s r (Rosenthal, 1994) | 0.10 | 0.30 | ≥0.50 |

| First Author | Clinical Group | Sample Size | Sample Details | Intervention (Reference) | Comparator/Control Group | Individual or Group Delivery | Session Number, Duration in Hours (h), and Frequency | Facilitator(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | (Diagnostic Tool) | Study Diagnostic Interview (Yes/No); Diagnosis Date; Diagnostic Evidence | Included Sample | Retention Rate (%) | Age (M, SD, Range) Gender (% Female, % Male) | Facilitator Training | ||||

| Altavilla and Strudwick (2022) UK | Depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and psychosis, recruited from an NHS secondary mental health setting. (NR cut-offs on CORE-OM, DASS-21) | No; Unspecified; Medical records. | 23 | 22/23 (95.65%) | NR, NR, 32–89 NR, NR | CFT (Gilbert, 2009, 2010; Lee & James, 2012; Welford, 2012) | N/A | Group (Four cohorts with 6–10 people) | 20, 2.5 h, weekly | Two clinical psychologists. Clinical work with CFT. |

| Asano et al. (2022) Japan | Treatment- resistant depression, recruited from the community. (≥20 on the BDI) | Yes; Unspecified; The Japanese M.I.N.I | 17 CFT: n = 10 TAU: n = 7 | Total: 17/18 (94.44%) CFT: 9/10 (90.00%) TAU: 7/7 (100.00%) | CFT: 39.80, 11.22, 24–56 80.00%, 20.00% TAU: 40.00, 11.46, 26–55 85.00%, 15.00% | CFT (Judge et al., 2012) | TAU | Group | 12, 1.5 h, weekly | One clinical psychologist, one industrial counsellor. 1/2 facilitators attended 3-day CFT workshop. Both CBT trained and supervised by PG. |

| Behrouzian et al. (2024) Iran | Bipolar disorder, recruited from a psychiatric clinic. | Yes; Unspecified; Bipolar disorder diagnosed by an expert clinician using the SCID-I | 26 CFT: n = 13 TAU: n = 13 | Total: 26/31 (86.66%) CFT: 13/16 (81.25%) TAU: 13/15 (86.66%) | CFT: 29.15, 6.44, NR 84.62%, 15.38% TAU: 28.46, 5.86, NR 76.92%, 23.08% | CFT (Gilbert, 2010, 2014; Gharraee et al., 2018) | TAU | Individual | 10, NR, weekly | NR NR |

| Clapton et al. (2018) UK | Depression and anxiety, recruited from an NHS Intellectual Disabilities service. (NR diagnostic tools) | No; Unspecified; Medical records. | 7 | 6/7 85.71% | 38.5, 15.6, NR 66.70%, 33.30% | CFT (Gilbert, 2010, 2014; Gilbert & Irons, 2004; Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Heriot-Maitland et al., 2014) | N/A | Group (Two cohorts with three people) | 6, 1.5 h, weekly | Two clinical psychologists, one trainee clinical psychologist. Lead facilitators with three years of CFT experience and supervision by PG. |

| Fox et al. (2021) USA | Distress at a clinical level, recruited from university counselling services. (≥64 on the OQ-45) | No; Unspecified; Unspecified. | 91 | 45/91 49.45% | 22.70, NR, 18–29 Among 75 participants who completed pre-treatment measures: 73.50%, 26.50%. | CFT (Gilbert, 2009, 2017; Gilbert & Choden, 2013). | N/A | Group (Eight cohorts of 7–14 people) One individual consolidation session every three weeks | 12, 2 h, weekly | Five clinical psychologists. 3/5 facilitators trained and supervised by PG. |

| Gharraee et al. (2018) Iran | Social anxiety disorder, recruited from clinical settings. (LSAS pre-treatment mean 74.1 and 73.1 for CFT and waitlist, respectively) | Yes; 2017–2018; SCID-I/CV conducted by two assessors (psychiatrist and clinical psychologist). | 34 CFT: n = 17 Waitlist: n = 17 | Total: 32/34 94.12% CFT: 17/17 100.00% Waitlist: 15/17 88.24% | CFT: 22.7, 4.58, NR 47.10%, 52.90% Waitlist: 22.00, 4.39, NR 47.10%, 52.90% | CFT for social anxiety disorder (Boersma et al., 2015, social anxiety protocol informed by Gilbert, 2010, 2014; Gilbert & Procter, 2006). | Waitlist | Individual | 12, 1 h, weekly | One clinical psychologist. Protocol adherence was assessed by an independent and anonymous clinical psychologist for 20% of sessions. |

| Gilbert et al. (2022) UK | Bipolar disorder, recruited from a specialist NHS Bipolar Service. | No; Unspecified; Medical records. | 13 | 6/13 46.15% | NR, NR, 31–60 40.00%, 60.00% | CFT (Gilbert, 2001, 2010) | N/A | Group | 25, NR, ~weekly | Two clinical psychologists. Trained and supervised by PG. |

| Gilbert and Procter (2006) UK | Personality disorder, recruited from an NHS Day Centre. (HADS anxiety and depression in clinical range) | No; Unspecified; Psychiatric diagnosis diagnosed a psychiatrist. | 9 | 6/9 66.67% | 45.20, 5.54, 39–51 66.60%, 33.30% | CFT (Gilbert & Irons, 2004) | N/A | Group | 12, 2 h, weekly | Facilitated by PG and a cognitive therapist. |

| Grodin et al. (2019) USA | PTSD, recruited from a specialist outpatient clinic. (≥31 on PCL-5) | No; Unspecified; Psychiatric diagnosis. | 22 | 16/22 72.73% | 52.60, 12.90, NR 4.00%, 96.00% | CFT (Kolts, 2015) | N/A | Group | 12, NR, NR | Four clinical psychologists (two facilitators in each group). Trained and supervised by RK. |

| Johannsen et al. (2022) Denmark | Prolonged grief disorder, recruited from a bereavement study. (≥25 on the PG-13) | No; Unspecified; Diagnostic tool. | Total: n = 82 CFT: n = 42 Waitlist: n = 40 | Total: 61/82 74.39% CFT: 26/42 61.90% Waitlist: 35/42 83.33% | Total: 60.50, 13.40, 23–83 67.10%, 32.90% CFT: 61.40, 13.60, NR 71.40%, 28.60% Waitlist: 59.50, 13.80, NR 62.5%, 37.5% | CFT adapted for prolonged grief. (Gilbert, 2009, 2014) | Waitlist | Group | 8, 2.25 h, weekly | Three clinical psychologists. Trained and supervised by PG. |

| Judge et al. (2012) UK | Transdiagnostic, recruited from NHS Community Mental Health Teams. (≥17 on the BDI) | No; Unspecified; Medical records. | 42 | 36/42 completed sessions: 85.71%. 27/42 completed measures: 64.29%. | 40.90, 8.80, 22–56 59.30%, 40.70% | CFT (Gilbert, 2009) | N/A | Group (Seven cohorts of ~five people) | 12–14, 2.25 h, weekly | NR Trained and supervised by PG. |

| Laithwaite et al. (2009) UK | Schizophrenia, Schizo-affective or bipolar affective disorder, recruited from a maximum- secure hospital. (NR) | No; Unspecified; Unspecified. | 19 | 18/19 94.74% | 36.90, 9.10, NR 0.00%, 100.00% | CFT (Gilbert, 2001) | N/A | Group (Three cohorts) | 20, NR, twice weekly | Two clinical psychologists, one advanced practitioner, one trainee clinical psychologist, and two assistant psychologists. NR |

| Lucre and Corten (2013) UK | Personality disorder, recruited from a specialist NHS Personality Disorder Service. | Yes; 2010; International PD examination completed by an NHS Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapist. | 10 | 8/10 80.00% | NR, NR, 18–54 77.70%, 22.20% | CFT (Gilbert, 2001) | N/A | Group | 16, NR, NR | Two psychotherapists. Trained and supervised by PG. |

| McLean et al. (2022) Australia | Transdiagnostic, recruited from specialist Sexual Assault services. (≥31 on PCL-5 or ≥10 and ≥8 on DASS-21 on depression and anxiety subscales, respectively). | No; No; Unspecified. | 36 | Pre to post-CFT: 30/36 83.33% Pre to follow-up: 25/36 69.44% | 41.10, 13.30, 18–65 100.00%, 0.00% | CFT (Lee & James, 2012; Gilbert, 2009, 2015) | N/A | Group (Four cohorts of 7–11 people) | 12, 2 h, weekly | One psychologist, one counsellor. Psychologist had 20 years’ clinical experience working with survivors of interpersonal trauma; trained and supervised by PG. |

| McManus et al. (2018) UK | Transdiagnostic, recruited from NHS Community Mental Health Teams. NR | No; Unspecified; Medical records. | 27 | 13/27 48.15% | 43, NR, 23–67 46.20%, 53.80% | CFT (Braehler et al., 2013; Gilbert, 2010; Welford, 2012) | N/A | Group (Four cohorts) One individual session (week 5) | 16, 2 h, weekly | Two facilitators per group: either clinical psychologists or trainee clinical psychologists. NR |

| Naismith et al. (2021) Colombia | Transdiagnostic, recruited from non-governmental organisations for low-income women. (either ≥34 on IES-R, or ≥10 on PHQ-9, or ≥8 on GAD-7). | No; Unspecified; Unspecified. | 41 | 10/41 24.39% | 37.80, 11.70, 19–52 100.00%, 0.00% | CFT (Gilbert, 2014) | N/A | Group | 5, 2.25 h, weekly | One clinical psychologist, one marriage and family therapist. NR |

| Noorbala et al. (2013) Iran | Depression, recruited from a psychiatric clinic. (≥20 on BDI) | Yes; Unspecified; Psychiatrist diagnosed major depressive disorder according to DSM-IV criteria. | Total: n = 22 CFT: n = 11 Waitlist: n = 11 | Total: 19/22 86.36% CFT: 9/11 81.82% Waitlist: 10/11 90.91% | 28.20, NR, 20–40 100.00%, 0.00% | CFT (Gilbert, 2005) | Waitlist | Group | 12, 2 h, twice weekly | NR NR |

| Petrocchi et al. (2021) Italy | Obsessive compulsive disorder, recruited from an anxiety and mood disorders unit. (≥14 on Y-BOCS) | Yes; Unspecified; OCD diagnosed by an expert clinician using the SCID-I | 8 | 8/8 100.00% | NR, NR, 34–41 50.00%, 50.00% | CFT (Gilbert & Choden, 2013) | N/A | Group | 8, 2 h, weekly | Two psychotherapists. One with 8 years of training with PG, one with five years of training in CFT. |

| Pol et al. (2024) The Netherlands | Personality disorder, recruited from a day-hospital. (≥14.93 on BPDSI-IV) | No; Unspecified; Unspecified | 12 | 9/12 75.00% | 39.30, 44.30, NR 100.00%, 0.00% | CFT (Gilbert et al., in press; Pol et al., 2020) | N/A | Group | 12, NR, weekly | One clinical psychologist. Basic and advanced training in CFT with PG. |

| Savari et al. (2021) Iran | Major depressive disorder, recruited from recruited from university counselling services. (≥20 on BDI) | Yes; NR; SCID-I | Total: 30 CFT: 15 Waitlist: 15 | Total: 30/30 100.00% CFT: 15/15 100.00% Waitlist: 15/15 100.00% | 24.30, 2.16, 21–29 100.00%, 0.00% | CFT (Gilbert, 2010; Gilbert & Choden, 2013) | N/A | Group | 8, 1.5 h, twice weekly for 4 weeks | Senior author. Attended CFT training with PG. |

| Stroud and Griffiths (2021) UK | Transdiagnostic, recruited from an inpatient mental health setting. (≥10 on CORE-OM) | No; Unspecified; Unspecified. | Total: n = 32 CFT: n = 19 TAU: n = 13 | NR | NR, NR, 18–60 59.40%, 40.60% | TAU & CFT (Gilbert, year unspecified) | TAU | Group (open format) | 6, 1 h, daily (Repeated cyclically every week over 4-months) | NR NR |

| First Author | Design | Outcome Measures | Timepoints | Main Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | (Measuring Tools) | (Reported p, ES (d), and Calculated g) | ||

| Altavilla and Strudwick (2022) UK | Mixed methods (Cohort: One group pre + post, and qualitative interviews) | Self-compassion (SCS) | Pre-intervention, Session 20, 3-month follow-up | a Significant increase in self-compassion (SCS) post-intervention (p = 0.008) |

| Asano et al. (2022) Japan | RCT (CFT vs. TAU) | Self-compassion (CEAS) Compassion from others (CEAS) Compassion to others (CEAS) | Pre-intervention, post-intervention | Change in self-compassion (CEAS) post-intervention (d = 1.08 L, g = 1.13 L) compared to TAU. Change in compassion from others (CEAS) post-intervention (d = 0.61 M, g = 0.66 M) compared to TAU. Change in compassion to others (CEAS) post-intervention (d = 0.14 VS, g = 0.15 VS) compared to TAU. |

| Behrouzian et al. (2024) Iran | RCT (CFT vs. TAU) | Self-compassion (SCS-SF) Self-criticism (SCRS) | Pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 2-month follow-up | No significant change in self-compassion (SCS-SF) post-intervention compared to TAU (p = 0.49, d = 0.50 M, g = 0.48 S). Significant decrease in self-criticism (SCRS) post-intervention compared to TAU (p < 0.001, d = −1.60 L, g = −1.55 L). |

| Clapton et al. (2018) UK | Mixed methods (Cohort: One group pre + post, and qualitative interviews) | Self-compassion (SCS-SF) Self-criticism (SCS-SF) | Pre-intervention, 2–4 weeks post-intervention | No significant change in self-compassion (SCS-SF) post-intervention (p = 0.674, d = 0.25 S, g = 0.23 S). Significant decrease in self-criticism (SCS-SF) post-intervention (p = 0.027, d = −2.04 L, g = −1.88 L). |

| Fox et al. (2021) USA | Cohort: One group pre + post | Self-compassion (CEAS) Compassion from others (CEAS) Compassion to others (CEAS) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) Self-criticism (DEQ) | Pre-intervention, session 6, post-intervention (session 12+) | Significant increase in self-compassion (CEAS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 0.75 M, g = 0.67 M). Significant increase in compassion from others (CEAS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 0.26 S, g = 0.26 S). No significant change in compassion to others (CEAS) post-intervention (p = 0.19, d = −0.08 VS, g = −0.08 VS). Significant decrease in inadequate self and hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −0.71 M, g = −0.70 M, and p < 0.001, d = −0.34 S, g = −0.33 S, respectively). Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 0.40 S, g = 0.40 S). Significant decrease in self-criticism (DEQ) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −0.50 M, g = −0.50 M). |

| Gharraee et al. (2018) Iran | RCT (CFT vs. Waitlist) | Self-compassion (SCS) Self-criticism (LOSC) | Pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 2-month follow-up | Significant increase in self-compassion (SSC) compared to waitlist control at post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 1.99 L, g = 1.94 L), which was maintained at follow-up (p = 0.39, d = −0.37 S, g = −0.36 S). Significant decrease in self-criticism (LOSC) compared to waitlist control at post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −1.91 L, g = −1.86 L), which further increased at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = 0.26 S, g = 0.25 S). |

| Gilbert et al. (2022) UK | Mixed methods (Cohort: One group pre + post, and qualitative interviews) | Self-compassion (CEAS) Compassion from others (CEAS) Compassion to others (CEAS) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) | Pre-intervention, 12 weeks, 32 weeks, and post-intervention (45 weeks) | An overall improvement in self-compassion and compassion from others (CEAS) were reported from baseline to 45 weeks (6 out of 6 participants improved, d = 1.29 L, g = 1.19 L, and 4 out of 6 participants improved, d = 0.39 S, g = 0.36 S, respectively). No overall improvement in compassion to others (CEAS) was reported from baseline to 45 weeks (3 out of 6 participants improved, d = −0.38 S, g = −0.35 S). An overall improvement in inadequate self, hated self, and reassured self (FSCRS) were reported from baseline to 45 weeks (6 out of 6 participants improved, d = −1.21 L, g = −1.11 L, 2 out of 6 participants improved, d = −0.21 S, g = −0.19 VS, and 5 out of 6 improved, d = 0.61 M, g = 0.56 M, respectively). |

| Gilbert and Procter (2006) UK | Cohort: One group pre + post | Self-compassion (Weekly Interval Contingent Diary Measuring Self-attacking and Self-soothing) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) External shame (OAS) | Pre-intervention (beginning of week 1), post-intervention (end of week 12) | Significant increase in self-compassion (Diary) post-intervention (p = 0.030, d = 4.49 L, g = 4.14 L). No significant change in inadequate self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.070, d = −2.73 L, g = −2.52 L). Significant decrease in hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.030, d = −2.04 L, g = −1.88 L). Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.030, d = 1.86 L, g = 1.71 L). Significant decrease in external shame (OAS) post-intervention (p = 0.030, d = −0.82 L, g = −0.75 M). |

| Grodin et al. (2019) USA | Cohort: One group pre + post (pilot study) | Self-compassion (SCS) | Pre- and post-intervention | No significant change in self-compassion (SCS) post-intervention (p = 0.34, d = 0.17 VS, g = 0.11 VS). |

| Johannsen et al. (2022) Denmark | RCT (CFT vs. Waitlist) | Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) | Pre-intervention, post-intervention, 3-month and 6-month follow-up | No significant change in inadequate self and hated self (FSCRS) compared to waitlist post-intervention (p = 0.24, d = −0.44 S, g = −0.43 S and p = 0.15, d = −0.08 VS, g = −0.08 VS, respectively). Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) compared to waitlist post-intervention (p = 0.001, d = 0.43 S, g = 0.43 S). |

| Judge et al. (2012) UK | Cohort: One group pre + post | Self-compassion (Weekly Interval Contingent Diary Measuring Self-attacking and Self-soothing) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) Internal shame (ISS) External shame (OAS) | Pre- and post-intervention | Significant increase in self-compassion (Diary) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 1.17 L, g = 1.15 L). Significant decrease in inadequate self and hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −1.35 L, g = −1.33 L and p < 0.001, d = −0.90 L, g = −0.88 L, respectively). Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 0.93 L, g = 0.91 L). Significant decrease in internal shame (ISS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −1.30 L, g = −1.28 L). Significant decrease in external shame (OAS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −0.55 M, g = −0.54 M). |

| Laithwaite et al. (2009) UK | Cohort: One group pre + post | Self-compassion (SCS) External shame (OAS) | Pre-intervention, mid-group (5 weeks), post-intervention, 6-week follow-up | a No significant change in self-compassion (SCS) post-intervention (p = 0.180, r = 0.22 S). a Significant decrease in external shame (OAS) post-intervention (p = 0.040, r = 0.04 <S). |

| Lucre and Corten (2013) UK | Mixed methods (Cohort: One group pre + post, and qualitative interviews) | Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) External shame (OAS) | Pre- and post-intervention (16 weeks), 1-year follow-up | a No significant change in inadequate self (FSCRS) at follow-up (p = 0.062). a Significant decrease in hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention, which was maintained at follow-up (p < 0.001). a Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention, which was maintained at follow-up (p < 0.001). a Significant decrease in external shame (OAS) post-intervention, which further decreased at follow-up (p = 0.011). |

| McLean et al. (2022) Australia | Cohort: One group pre + post | Self-compassion (CEAS) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) Global shame (EISS) External shame (OAS) | Pre-intervention (2 weeks pre-group), post-intervention (12 weeks), 3-month follow-up | Significant increase in self-compassion (CEAS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 1.82 L, g = 1.79 L) and at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = 1.57 L, g = 1.55 L). Significant decrease in inadequate self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −1.59 L, g = −1.56 L) and at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = −1.73 L, g = −1.70 L). Significant decrease in hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −0.98 L, g = −0.97 L) and at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = −0.94 L, g = −0.92 L). Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = 1.20 L, g = 1.18 L) and at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = 1.11 L, g = 1.09 L). Significant decrease in global shame (EISS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −1.70 L, g = −1.67 L) at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = −1.35 L, g = −1.32 L). Significant decrease in external shame (OAS) post-intervention (p < 0.001, d = −1.24 L, g = −1.22 L) and at follow-up (p < 0.001, d = −0.77 M, g = −0.75 M). |

| McManus et al. (2018) UK | Mixed methods (Cohort: One group pre + post, and qualitative interviews) | Self-compassion (SCS) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) External shame (OAS) | Pre- and post-intervention (week 16) | a Significant increase in self-compassion (SCS) post-intervention (p = 0.010). a Significant decrease in inadequate self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.030). a Significant decrease in hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.020). a No significant change in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.070). a Significant decrease in external shame (OAS) post-intervention (p = 0.010). |

| Naismith et al. (2021) Colombia | Cohort: One group pre + post | Self-criticism (Inadequate Self, Hated Self; FSCRS) | Pre- (5 weeks before intervention) and post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up | b Inadequate self (FSCRS) reliably improved for 5 out of 10 participants post-intervention, and 5 out of 9 participants at follow-up. b Hated self (FSCRS) reliably improved for 4 out of 5 participants, and 3 out of 5 participants at follow-up (5 scored under 6 pre-intervention and were excluded). |

| Noorbala et al. (2013) Iran | Case controlled clinical trial (CFT vs. Waitlist) | Self-criticism (Comparative and Internalised; LOSC) | Pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 2-month follow-up | a No significant change in comparative self-criticism (LOSC) post-intervention (p = 0.491) or at follow-up (p = 0.108). a No significant change in internalised self-criticism (LOSC) post-intervention (p = 0.491) or at follow-up (p = 0.272). |

| Petrocchi et al. (2021) Italy | Multiple baseline design | Self-compassion (Common Humanity; SCS) Self-criticism (Inadequate Self & Reassured Self; FSCRS) | Baseline, pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 1-month follow-up | No significant change in self-compassion (Common Humanity; SCS) post-intervention (p = 0.11, g = 0.49 S) and at follow-up (p = 0.230, g = 0.57 M). Significant decrease in inadequate self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.030, g = −0.29 S), which was not maintained at follow-up (p = 0.110, g = −0.63 M). Significant increase in reassured-self (FSCRS) post-intervention (p = 0.040, g = 0.35 S), which was not maintained at follow-up (p = 0.100, g = 0.32 S). |

| Pol et al. (2024) The Netherlands | Multiple baseline design | Self-compassion (SCS-SF) Self-criticism (FSCRS) | Baseline, pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 6-week follow-up | b Self-compassion (SCS-SF) reliably improved for 3 out of 9 participants post-intervention and 5 out of 9 at follow-up. 5 out of 9 participants and 4 out of 9 participants showed no change post-intervention and at follow-up, respectively. b Self-criticism (FSCRS) reliably improved for 6 out of 9 participants post-intervention and at follow-up. 3 out of 9 participants showed no change. |

| Savari et al. (2021) Iran | RCT (CFT vs. Waitlist) | Self-compassion (SCS-SF) Self-criticism (FSCRS; Inadequate Self, Hated Self, & Reassured Self) | Pre- and post-intervention | Significant increase in self-compassion (SCS-SF) post-intervention compared to waitlist (p = 0.010, d = 0.75 M, g = 0.73 M). No significant change in inadequate self (FSCRS) post-intervention compared to waitlist. Significant decrease in hated self (FSCRS) post-intervention compared to waitlist (p = 0.030, d = −1.00 L, g = −0.97 L). Significant increase in reassured self (FSCRS) post-intervention compared to waitlist (p < 0.001, d = 1.20 L, g = 1.17 L). |

| Stroud and Griffiths (2021) UK | Cohort analytic (Two group: CFT vs. TAU pre + post) | Self-compassion (VAS) Compassion to Others (VAS) | Pre-, every session, and post-intervention | a Significant increase in self-compassion (VAS) across all sessions compared to TAU (p < 0.001, d = 0.24 S). a Significant increase in compassion to others (VAS) across all sessions compared to TAU (p < 0.001, d = 0.18 VS). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, N.; Ashcroft, K. The Effectiveness of Compassion Focused Therapy for the Three Flows of Compassion, Self-Criticism, and Shame in Clinical Populations: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081031

Brown N, Ashcroft K. The Effectiveness of Compassion Focused Therapy for the Three Flows of Compassion, Self-Criticism, and Shame in Clinical Populations: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081031

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Naomi, and Katie Ashcroft. 2025. "The Effectiveness of Compassion Focused Therapy for the Three Flows of Compassion, Self-Criticism, and Shame in Clinical Populations: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081031

APA StyleBrown, N., & Ashcroft, K. (2025). The Effectiveness of Compassion Focused Therapy for the Three Flows of Compassion, Self-Criticism, and Shame in Clinical Populations: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081031