Verification of the Impact of Sports Event Service Quality and Host Destination Image on Sports Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions Through Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sport Events (Participation and Spectatorship) and Subjective Well-Being

2.2. Event Service Quality

2.3. Host Destination Image

2.4. Satisfaction

2.5. Behavioral Intentions

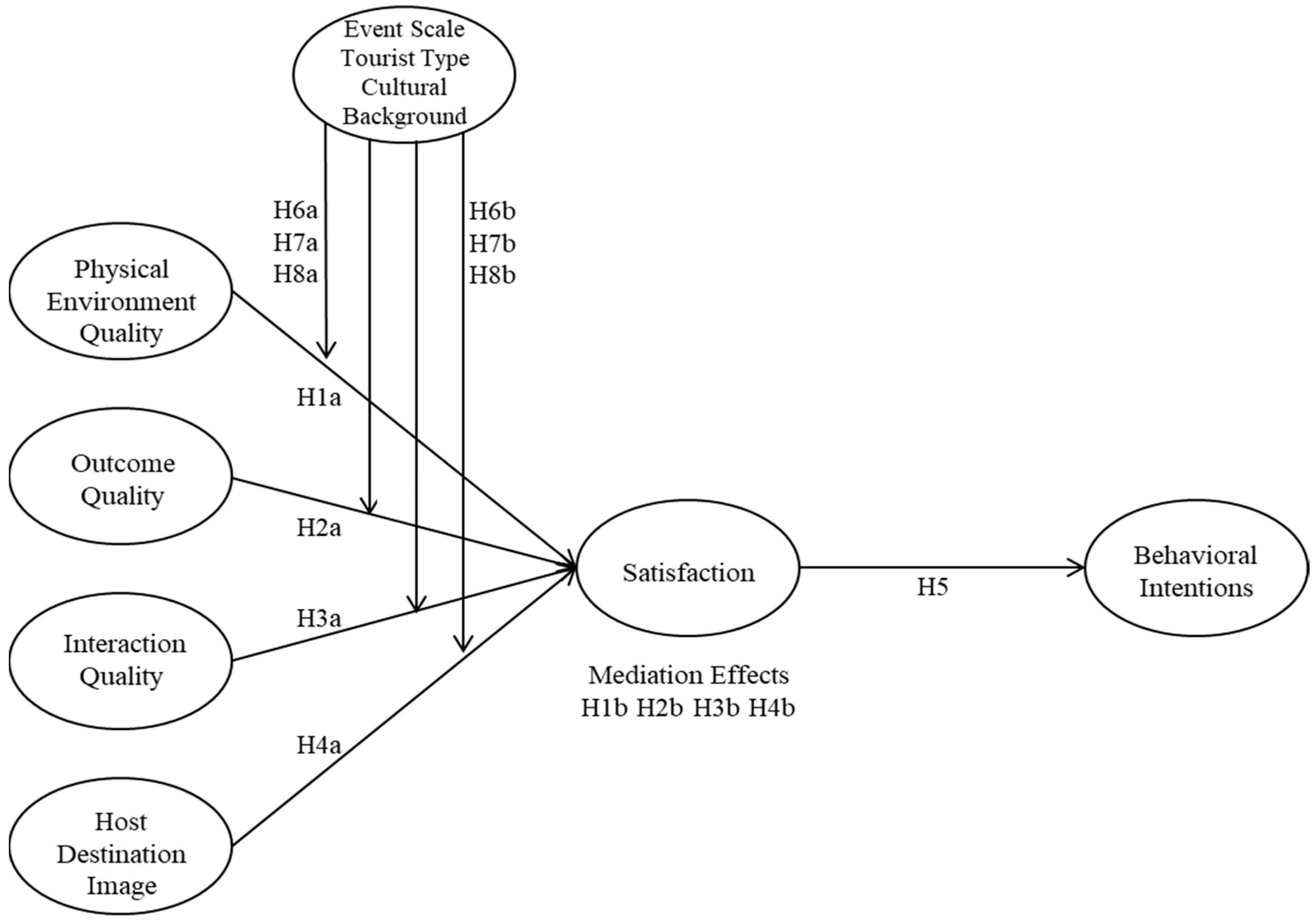

2.6. Structural Relationships Between Event Service Quality, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions

2.7. Structural Relationships Between Host Destination Image, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions

2.8. Moderating Effects of Event Scale (Large Scale/Small Scale), Tourist Type (Spectator/Athlete), and Cultural Context (Eastern/Western)

3. Methods

3.1. Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling (MASEM)

3.2. Data Sources

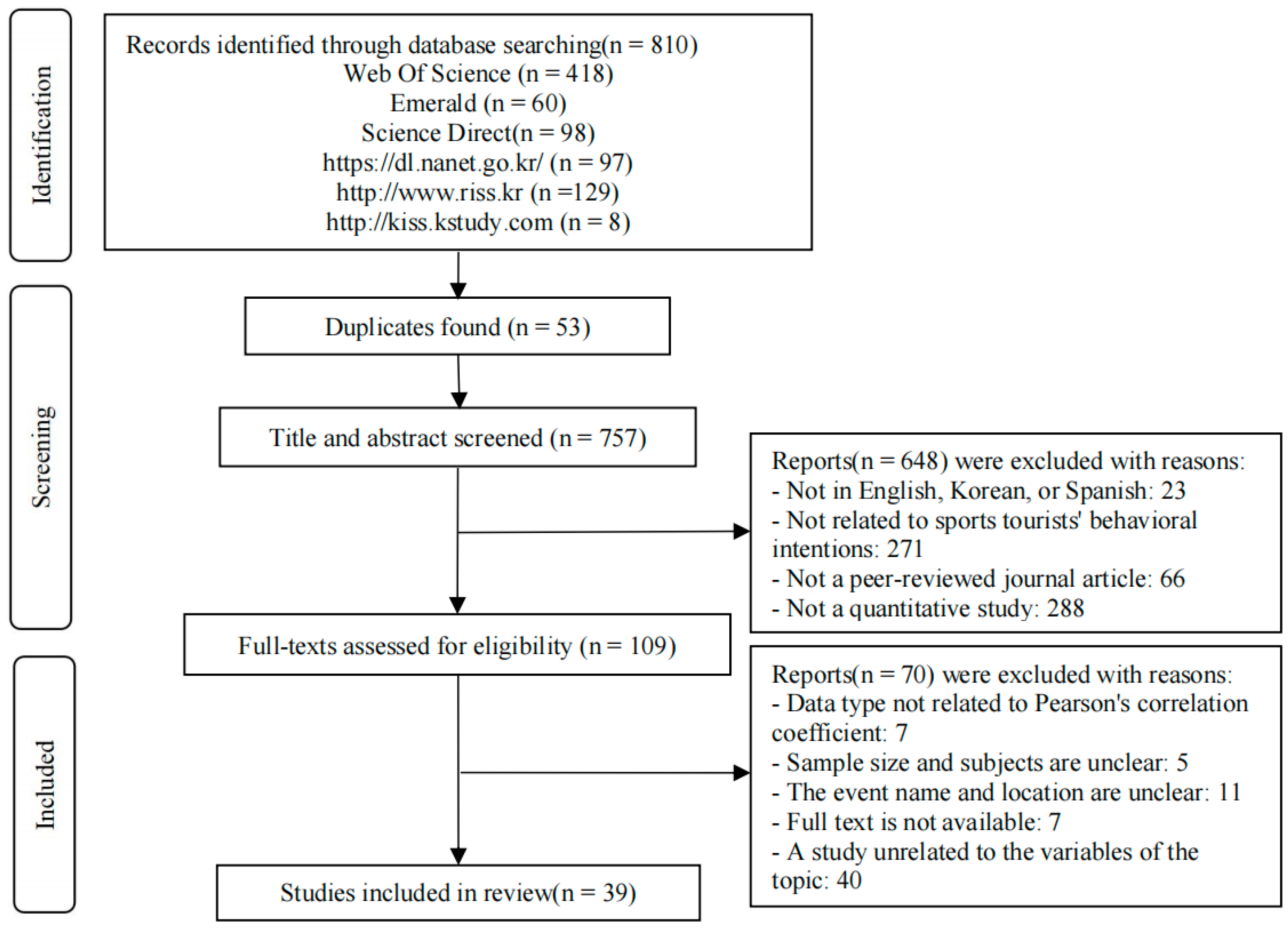

3.3. Literature Selection

3.4. Information Coding

3.5. Publication Bias and Heterogeneity Test

3.6. Mediation and Moderation Effects

4. Results

4.1. Meta-Analysis Results

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis Results

4.3. Mediating Effects of Satisfaction

4.4. Moderating Effects of Sports Event Scale, Tourist Type, and Cultural Context

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | N | PEQ_ OQ | PEQ_ IQ | PEQ_ DI | PEQ_ SA | PEQ_ BI | OQ_ IQ | OQ_ DI | OQ_ SA | OQ_ BI | IQ_ DI | IQ_ SA | IQ_ BI | DI_ SA | DI_ BI | SA_ BI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ferri et al., 2021) | 236 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.72 | |||||||||

| (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2022) | 866 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 0.66 | |||||||||

| (Pahrudin et al., 2024) | 221 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.7 | 0.89 | |||||||||

| (Vegara-Ferri et al., 2020) | 115 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.78 | |||||||||

| (Elahi et al., 2020) | 382 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.47 | ||||||||||||

| (Jeong et al., 2019) | 350 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.73 | ||||||||||||

| (Quirante-Mañas et al., 2023) | 866 | 0.39 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.5 | 0.44 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| (Song et al., 2023) | 485 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| (Song et al., 2023) | 459 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.47 | ||||||||||||

| (Song et al., 2024) | 313 | 0.5 | 0.36 | 0.5 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| (Song et al., 2024) | 364 | 0.41 | 0.4 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.4 | 0.42 | |||||||||

| (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2021) | 686 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.3 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.28 | |||||||||

| Yamaguchi and Yoshida (2022) | 434 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.49 | |||||

| S. C. Ma and Kaplanidou (2021) | 573 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.53 | |||||||||

| (Vicente et al., 2021) | 366 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0.47 | ||||||||||||

| (Zhu et al., 2024) | 702 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.07 | ||||||

| An and Yamashita (2024) | 411 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.44 | |||||||||

| (Wang et al., 2021) | 796 | 0.66 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.66 | |||||||||

| (Leon et al., 2022) | 384 | 0.46 | 0.3 | 0.51 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.34 | |||||||||

| (Y. Lee et al., 2019) | 431 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.43 | |||||||||

| (Xiao et al., 2020) | 308 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.6 | 0.61 | ||||||

| (Ho Kim et al., 2013) | 623 | 0.4 | 0.65 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.47 | |||||||||

| (Yoshida et al., 2013) | 396 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.22 | ||||||||||||

| (K. A. Kim et al., 2019) | 281 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.3 | ||||||||||||

| (S. Lee, 2016) | 262 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.87 | 0.8 | 0.74 | |||||||||

| (Kwon et al., 2013) | 300 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.7 | |||||

| (Min, 2020) | 396 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.6 | 0.76 | 0.63 |

| Min and Lee (2019) | 292 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.46 | |||||||||

| H. Kim and Park (2008) | 349 | 0.42 | 0.3 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.59 | |||||||||

| Min and Woo (2023) | 217 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.42 | ||||||||||||

| J. Lee and Kim (2017) | 286 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| Seok and Cho (2020) | 342 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.53 | |||||||||

| (J. H. Park, 2011) | 222 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.58 | ||||||||||||

| J. Kim and Kim (2024) | 305 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.57 | ||||||||||||

| (Ko, 2009) | 363 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.36 | ||||||

| (Ji, 2011) | 389 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.8 | |||||

| Oh and Song (2020) | 339 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.6 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.54 | |||||

| M. Kim and Lee (2018) | 269 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.49 | 0.56 | |||||

| J. Park and Park (2015) | 274 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.47 | ||||||||||||

| H. Park and Shin (2017) | 300 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 0.46 | |||||||||

| (J. Lee, 2024) | 382 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

References

- An, B., & Yamashita, R. (2024). A study of event brand image, destination image, event, and destination loyalty among international sport tourists. European Sport Management Quarterly, 24(2), 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M. H., Ottesen, L., & Thing, L. F. (2019). The social and psychological health outcomes of team sport participation in adults: An integrative review of research. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 47(8), 832–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). A model of destination image formation. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(4), 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barili, F., Parolari, A., Kappetein, P. A., & Freemantle, N. (2018). Statistical Primer: Heterogeneity, random-or fixed-effects model analyses? Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, 27(3), 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaia, R., Correia, A., Rosado, A., Maroco, J., & Ross, S. (2012). The effects of emotions on football spectators’ satisfaction and behavioural intentions. European Sport Management Quarterly, 12(3), 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaia, R., Yoshida, M., & Kim, Y. (2023). Service quality and its effects on consumer outcomes: A meta-analytic review in spectator sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(3), 897–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. K., & Cronin, J. J., Jr. (2001). Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing, 65(3), 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Manrique, D., Nuviala, R., Pappous, A., Puga-González, E., & Nuviala, A. (2021). The mediation of emotions in sport events: A case study in badminton. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(4), 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevik, H., & Şimşek, K. Y. (2020). The effect of event experience quality on the satisfaction and behavioral intentions of Motocross World Championship spectators. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 21(2), 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. (2004). Beyond impact: A general model for sport event leverage. In Sport tourism: Interrelationships, impacts and issues (pp. 226–252). Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. (2006). Towards social leverage of sport events. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 11(2), 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. Journal of Travel Research, 17(4), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L., & Love, L. L. (1995). The predictive validity of alternative approaches to evaluating quality of a festival. Journal of Travel Research, 34(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., Jr., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, A. (2024). Exploring visitor’s satisfaction and recommendation intention at mega sporting events using the SOR model with host country hospitability as moderator. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davras, Ö., & Özperçin, İ. (2023). The relationships of motivation, service quality, and behavioral intentions for gastronomy festival: The mediating role of destination image. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 15(4), 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, M. B., Everett, S., & McCabe, S. (2022). Events as catalysts for communal resistance to overtourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 96, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eather, N., Wade, L., Pankowiak, A., & Eime, R. (2023). The impact of sports participation on mental health and social outcomes in adults: A systematic review and the ‘Mental Health through Sport’conceptual model. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, A., Moradi, E., & Saffari, M. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of tourists’ satisfaction in sport event: Mediating role of destination image. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 21(2), 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, S., Lovegrove, H., Newland, B. L., & Green, B. C. (2016). Image recovery from negative media coverage of a sport event: Destination, venue, and event considerations. Sport Management Review, 19(3), 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, A., Cabello-Manrique, D., Roca-Cruz, A. F., & Nuviala, A. (2022). The influence of small-scale sporting events on participants’ intentions to recommend the host city. Sustainability, 14(13), 7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martínez, A., Tamayo-Fajardo, J. A., Nuviala, R., Cabello-Manrique, D., & Nuviala, A. (2021). The management of major sporting events as an antecedent to having the city recommended. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, J. M. V., Castro, M. C., & Sánchez, S. A. (2021). Percepción de calidad, impacto sociocultural, imagen de destino e intenciones futuras del turista participante en un evento náutico sostenible. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 16(50), 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleshman, S. F., & Kaplanidou, K. (2023). Predicting active sport participant’s approach behaviors from emotions and meaning attributed to sport event experience. Event Management, 27(1), 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R., Mas, I. M., Romero, A. B., & Blázquez-Salom, M. (Eds.). (2020). Tourism and degrowth: Towards a truly sustainable tourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fourie, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2011). The impact of mega-sport events on tourist arrivals. Tourism management, 32(6), 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getz, D. (2008). Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tourism Management, 29(3), 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D., & Andersson, T. (2020). Testing the event travel career trajectory in multiple participation sports. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 24(3), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2014). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H. J. (1998). Sport tourism: A critical analysis of research. Sport Management Review, 1(1), 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajo, N. S., & Khen, M. H. S. (2020). Effect of service quality on visitor satisfaction, destination image and destination loyalty–Practical, theoretical and policy implications to avitourism. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 18(4), 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Yolal, M., Ribeiro, M. A., & Panosso Netto, A. (2017). Impact of trust on local residents’ mega-event perceptions and their support. Journal of Travel Research, 56, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. A., & Wang, J. (2024). The Qatar World Cup and Twitter sentiment: Unraveling the interplay of soft power, public opinion, and media scrutiny. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 59(5), 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ho Kim, T., Jae Ko, Y., & Min Park, C. (2013). The influence of event quality on revisit intention: Gender difference and segmentation strategy. Managing Service Quality, 23(3), 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y., Ballouli, K., Bernthal, M. J., & Choi, W. (2024). Making sense of stimuli-local image fit in the sport venue: Mediating effects of sense of home and touristic experience on local and visiting spectators. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 33(1), 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, M., & Jordan, J. S. (2020). Athletic goal achievement: A critical antecedent of event satisfaction, re-participation intention, and future exercise intention in participant sport events. Sport Management Review, 23(2), 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jak, S., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2020). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling with moderating effects on SEM parameters. Psychological Methods, 25(4), 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, W., Ko, Y. J., Wann, D. L., & Kim, D. (2017). Does spectatorship increase happiness? The energy perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 31(4), 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y., & Kim, S. (2020). A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(4), 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y., Kim, S. K., & Yu, J. G. (2019). Determinants of behavioral intentions in the context of sport tourism with the aim of sustaining sporting destinations. Sustainability, 11(11), 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M. (2011). An influence of sports event service quality on customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty, and revisit. Journal of MICE & Tourism Research, 11(1), 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Karakose, T., Tulubaş, T., Kanadli, S., & Gurr, D. (2025). What factors mediate the relationship between principal leadership and teacher professional learning? Evidence from meta-analytic structural equation modelling (MASEM). Journal of Educational Administration, 63(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, H., Gradidge, S., Gibson, N., Harvey, A., Roeloffs, S., Zawisza, M., & Forwood, S. (2023). Attending live sporting events predicts subjective wellbeing and reduces loneliness. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 989706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., & Park, Y. (2008). The effects of sports events at the Seoul Plaza on the image and royalty, satisfaction of the region. Korean Journal of Physical Education, 47(1), 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., & Kim, R. (2024). A study on the relationship between service environment, participation satisfaction, and tourism image of sports tourism events: Centering on winter youth Olympic games Gangwon 2024. Journal of Tourism Enhancement, 12, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Kim, Y., & Kim, D. (2017). Improving well-being through hedonic, eudaimonic, and social needs fulfillment in sport media consumption. Sport Management Review, 20(3), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. A., Byon, K. K., Baek, W., & Williams, A. S. (2019). Examining structural relationships among sport service environments, excitement, consumer-to-consumer interaction, and consumer citizenship behaviors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Lee, M. (2018). The structural relationship between perceived service quality, customer satisfaction, and recommendation intention of sport event participants. Korean Journal of Sport, 16(1), 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. K., Park, J. A., & Kim, W. (2016). The mediating effect of destination image on the relationship between spectator satisfaction and behavioral intentions at an international sporting event. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(3), 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, K., Nakagawa, K., & Sato, S. (2024). Watching sport enhances well-being: Evidence from a multi-method approach. Sport Management Review, 27(4), 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, B., Fyall, A., & Jones, I. (2017). Sport mega-events and nation branding: Unique characteristics of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, South Africa. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29, 900–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H. (2009). The relationship among service quality of sports event, participants’ satisfaction, re-participation intention, word-of-mouth intention. Korean Journal of Tourism Research, 24(5), 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kogoya, K., Guntoro, T. S., & Putra, M. F. P. (2022). Sports event image, satisfaction, motivation, stadium atmosphere, environment, and perception: A study on the biggest multi-sport event in Indonesia during the pandemic. Social Sciences, 11(6), 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronios, K., Kriemadis, A., & Papadopoulos, A. (2019). Exploring service quality and its customer consequences in the sports spectating sector. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 8(1), 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramareva, N., & Grix, J. (2021). Understanding public diplomacy, nation branding and soft power in showcasing places via sports mega-events. In N. Papadopoulos, & M. Cleveland (Eds.), Marketing countries, places, and place-associated brands (pp. 298–318). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroshus, E. (2016). Variability in institutional screening practices related to collegiate student-athlete mental health. Journal of Athletic Training, 51(5), 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuok, A. C., Chio, D. K., & Pun, A. C. (2021). Elite athletes’ mental well-being and life satisfaction: A study of elite athletes’ resilience and social support from an Asian unrecognised National Olympic Committee. Health Psychology Report, 10(4), 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumah, E. P., & Wahyudin, N. (2024). Sporting event quality: Destination image, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Event Management, 28(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W., Kim, Y., & Park, S. (2013). The impact of mega-sporting events service quality and spectator satisfaction on sport consumption behaviors: The case of the 2011 International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) World Championship. Korean Journal of Sport Management, 18(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, R. S. (2013). Successfully combining meta-analysis and structural equation modeling: Recommendations and strategies. Journal of Business and Psychology, 28, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. W., Shin, S., Bunds, K. S., Kim, M., & Cho, K. M. (2014). Rediscovering the positive psychology of sport participation: Happiness in a ski resort context. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. (2024). Effect of service quality of marine sports events on use satisfaction and post visit behavioral intention. Korean Journal of Sport, 22(3), 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., & Kim, T. (2017). Effect of sports event choosing properties on local brand image & intention to revisit. Korean Journal of Sport Science, 26(6), 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. (2016). The influence of mega sports event qualities on perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty focused on visitors of the IAAF World Championship Daegu. Event & Convention Research, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y., Kim, M. L., Koo, J., & Won, H. J. (2019). Sport volunteer service performance, image formation, and service encounters. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 20(2), 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M., Hinojosa-Ramos, M. V., León-Lopez, A., Belli, S., López-Raventós, C., & Florez, H. (2022). Esports events trend: A promising opportunity for tourism offerings. Sustainability, 14(21), 13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lera-López, F., Ollo-López, A., & Sánchez-Santos, J. M. (2021). Is passive sport engagement positively associated with happiness? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. W., Hsu, S. Y., Ho, J. L., & Lai, M. Y. (2020). Behavioral model of middle-aged and seniors for bicycle tourism. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. C., & Kaplanidou, K. (2021). Effects of event service quality on the quality of life and behavioral intentions of recreational runners. Leisure Sciences, 44(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. M., Ma, S. C., & Chen, S. F. (2022). The influence of triathletes’ serious leisure traits on sport constraints, involvement, and participation. Leisure Studies, 41(1), 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaz-González, A. M., Sahelices-Pinto, C., Mendaña-Cuervo, C., & García-Tascón, M. (2020). Overall quality of sporting events and emotions as predictors of future intentions of duathlon participants. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mosko, E., & Munsters, W. (2018). Sport tourism: A growth market considered from a cultural perspective. Ido movement for culture. Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology, 18(4), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Cevallos, D., Alguacil, M., & Calabuig Moreno, F. (2020). Influence of brand image of a sports event on the recommendation of its participants. Sustainability, 12(12), 5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, I., Matić, R., Alexandris, K., Maksimović, N., Milošević, Z., & Drid, P. (2021). Destination image, sport event quality, and behavioral intentions: The cases of three world sambo championships. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(7), 1150–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D. (2020). The effect of international sporting event marketing mix (7Ps) on foreign spectators’ destination image, satisfaction and revisit intention: An empirical evidence from 2019 Gwangju FINA world championships. Korean Journal of Sport Science, 31(4), 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D., & Lee, W. (2019). Examining the impact of event quality on spectators’ destination image, country image and behavioral intention: A case of Tour de Korea. Korean Journal of Sport Science, 30(1), 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, D., & Woo, S. (2023). Structural relationships among perceived sporting event quality, image, trust, satisfaction, and loyalty of small-scale golf tournament participants: A case of Korea family golf challenge. Korean Journal of Sport Science, 34(2), 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M., Gogishvili, D., Wolfe, S. D., Gaffney, C., Hug, M., & Leick, A. (2023). Peak event: The rise, crisis and potential decline of the Olympic games and the world cup. Tourism Management, 95, 104657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S., & Song, G. (2020). The effect of service quality of sports event to regional image and revisit intention: Focused on the Jeongeup Donghak Marathon. Journal of Tourism & Leisure Research, 32(12), 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oort, F. J., & Jak, S. (2016). Maximum likelihood estimation in meta-analytic structural equation modeling. Research Synthesis Methods, 7(2), 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahrudin, P., Wang, C. C., Liu, L. W., Lu, C., & Haq, M. B. U. (2024). Do satisfied visitors intend to revisit a large sports event? A case study of a large sports event in Indonesia. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 105(1), 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H., & Shin, S. (2017). The effect of service quality gators on gallery’s satisfaction of KLPGA Tour. Journal of Sport Science, 30, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., & Park, S. (2015). Structural relationships among service quality of sports events and host city image, reputation and revisit intention: Revolving around sports events held in small and medium sized cities. Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies, 60, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. H. (2011). The relationship among service environment, participation satisfaction, and image of tour destination regarding sport tourism events. Korean Journal of Sport Management, 16(3), 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett, D., & Brooks, T. J. (2018). Examining the relationship between satisfaction, intentions, and post-trip communication behaviour of active event sport tourists. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 22(4), 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2012). Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 51(3), 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H. (2004). Calculating the regional economic impact of the Olympic Games. European Sport Management Quarterly, 4, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirante-Mañas, M., Fernández-Martínez, A., Nuviala, A., & Cabello-Manrique, D. (2023). Event quality: The intention to take part in a popular race again. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 151, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, A., Brandao, F., & Sousa, A. C. (2018). Motivation-based cluster analysis of international tourists visiting a World Heritage City: The case of Porto, Portugal. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H., Uysal, M., & Brown, K. (2011). Relationship between destination image and behavioral intentions of tourists to consume cultural attractions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(5), 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1333–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2001). Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, S. A., Beck, J. T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). The role of culture in international relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 78(5), 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. L. P. D. (2013). Quality of life in professional, semiprofessional, and amateur athletes: An exploratory analysis in Brazil. Sage Open, 3(3), 2158244013497723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, C., & Cho, T. (2020). The effect of sports event quality on relationship quality of participants. Korea Journal of Sports Science, 29(4), 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonk, D. J., Bravo, G. A., Velez-Colon, L., & Lee, C. (2017). Measuring event quality, satisfaction, and intent to return at an international sport event: The ICF Canoe Slalom World Championships. Journal of Global Sport Management, 2(2), 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonk, D. J., & Chelladurai, P. (2008). Service quality, satisfaction, and intent to return in event sport tourism. Journal of Sport Management, 22(5), 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, M. A., Dwyer, B., & Rufer, L. (2018). An evolving experience: An investigation of the impact of sporting event factors on spectator satisfaction. Journal of Global Sport Management, 3(1), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Chen, J. M., Rao, X., & Wu, M. (2023). A comparison study on the behavioral intention of marathon runners in the United States and China. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Zeng, W., Chen, J. M., & Hsu, M. K. (2024). Exploring the attitudes and behavioral intentions of marathon racers: A cross-national inquiry. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 29(5), 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, H., & Block, J. (2022). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM): New tricks of the trade. Management Review Quarterly, 72(3), 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A. J. (2009). Publication bias. In H. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 435–452). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Szathmári, A. (2025). Navigating the playing field: Reimagining the sports industry in the face of accelerated climate change. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 60(3), 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R. K. (1993). Consumer expectations and the measurement of perceived service quality. Journal of Professional Services Marketing, 8(2), 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, H. D., & Yamini, S. (2022). Meta-analytic structural equation modeling testing the rival assumptions of self-control and social bonds theories. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 66, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N. D., Alexandris, K., Tsigilis, N., & Karvounis, S. (2013). Predicting spectators’ behavioural intentions in professional football: The role of satisfaction and service quality. Sport Management Review, 16(1), 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N. D., Kaplanidou, K., & Karabaxoglou, I. (2015). Effect of event service quality and satisfaction on happiness among runners of a recurring sport event. Leisure Sciences, 37(1), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M., Ryan, C., & Lockyer, T. (2002). Culture and evaluation of service quality—A study of the service quality gaps in a Taiwanese setting. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 7(2), 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzetzis, G., Alexandris, K., & Kapsampeli, S. (2014). Predicting visitors’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions from service quality in the context of a small-scale outdoor sport event. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 5(1), 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegara-Ferri, J. M., López-Gullón, J. M., Valantine, I., Diaz Suarez, A., & Angosto, S. (2020). Factors influencing the tourist’s future intentions in small-scale sports events. Sustainability, 12(19), 8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, M. M., Herrero, D. C., Sánchez, S. A., & Prieto, J. P. (2021). Calidad percibida e intenciones futuras en eventos deportivos: Segmentación de participantes de carreras por montaña. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 16(50), 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K. L., & Blodgett, J. G. (1994). The importance of servicescapes in leisure service settings. Journal of Services Marketing, 8(3), 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, S. C. (2019). Including papers in languages other than English in systematic reviews: Important, feasible, yet often omitted. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 111, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Li, Y., & Wong, J. W. C. (2021). Exploring experiential quality in sport tourism events: The case of Macau Grand Prix. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 9(1), 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. (2006). Sports tourism research 2000–2004: A systematic review of knowledge and a meta-evaluation of methods. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 11, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R. A., & Oliver, R. L. (1991). The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Ren, X., Zhang, P., & Ketlhoafetse, A. (2020). The effect of service quality on foreign participants’ satisfaction and behavioral intention with the 2016 Shanghai International Marathon. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 21(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S., & Yoshida, M. (2022). Effect of consumer experience quality on participant engagement in Japanese running events. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 31(4), 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M., James, J. D., & Cronin, J. J. (2013). Value creation: Assessing the relationships between quality, consumption value and behavioural intentions at sporting events. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 14(2), 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Lee, D., Judge, L. W., & Johnson, J. E. (2014). The relationship among service quality, satisfaction, and future attendance intention: The case of Shanghai ATP Masters 1000. International Journal of Sports Science, 4(2), 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X., Pyun, D. Y., & Manoli, A. E. (2024). Assessing the psychological pathways of esports events spectators: An application of service quality and its antecedents and consequences. European Sport Management Quarterly, 25, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Study | Method | N. | Related Variables | Tourist Type | Event Name | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Ferri et al., 2021) | Correlational | 236 | IQ, DI, SA, BI | Athlete | Spanish Half Marathon | Spain |

| 2 | (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2022) | Correlational | 866 | PEQ, OQ, SA, BI | Athlete | Spanish 21 km Marathon | Spain |

| 3 | (Pahrudin et al., 2024) | Correlational | 221 | PEQ, IQ, SA, BI | Spectator | MotoGP Grand Prix | Indonesia |

| 4 | (Vegara-Ferri et al., 2020) | Correlational | 115 | PEQ, IQ, DI, BI | Spectator | International Sailing Event | Spain |

| 5 | (Elahi et al., 2020) | Correlational | 382 | DI, SA, BI | Spectator | Iran Pro League (Football) | Iran |

| 6 | (Jeong et al., 2019) | Correlational | 350 | OQ, SA, BI | Athlete | Gyeongju International Marathon | Korea |

| 7 | (Quirante-Mañas et al., 2023) | Correlational | 866 | PEQ, OQ, SA, BI | Athlete | Granada Marathon | Spain |

| 8 | (Song et al., 2023) | Correlational | 485 459 | OQ, BI, DI | Athlete | Xiamen and Chicago Marathon | China USA |

| 9 | (Song et al., 2024) | Correlational | 313 364 | PEQ, OQ, DI, BI | Athlete | Chicago and Xiamen Marathon | USA China |

| 10 | (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2021) | Correlational | 686 | PEQ, OQ, SA, BI | Spectator | European Badminton Championships | Spain |

| 11 | (Yamaguchi and Yoshida, 2022) | Correlational | 434 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Athlete | Ako City Marathon | Japan |

| 12 | S. C. Ma and Kaplanidou (2021) | Correlational | 573 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, BI | Athlete | Taiwan Marathon | China |

| 13 | (Vicente et al., 2021) | Correlational | 366 | PEQ, IQ, BI | Athlete | Trail Running Competition | Spain |

| 14 | (Zhu et al., 2024) | Correlational | 702 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Spectator | Esports Tournament | China |

| 15 | An and Yamashita (2024) | Correlational | 411 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, DI | Athlete | Reykjavik Marathon | Iceland |

| 16 | (Wang et al., 2021) | Correlational | 796 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA | Spectator | The 66th Macau Grand Prix | China |

| 17 | (Leon et al., 2022) | Correlational | 384 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, BI | Spectator | Esports Tournament | Ecuador |

| 18 | (Y. Lee et al., 2019) | Correlational | 431 | IQ, DI, SA, BI | Spectator | Major Athletics Event | Korea |

| 19 | (Xiao et al., 2020) | Correlational | 308 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Athlete | Shanghai Marathon | China |

| 20 | (Ho Kim et al., 2013) | Correlational | 623 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, BI | Spectator | College Basketball Game | USA |

| 21 | (Yoshida et al., 2013) | Correlational | 396 | OQ, IQ, BI | Spectator | NCAA Division I College Football Game | USA |

| 22 | (K. A. Kim et al., 2019) | Correlational | 281 | PEQ, IQ, BI | Spectator | Korea Ladies Professional Golf Tour | Korea |

| 23 | (S. Lee, 2016) | Correlational | 262 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA | Spectator | Daegu IAAF World Championships | Korea |

| 24 | (Kwon et al., 2013) | Correlational | 300 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Spectator | Daegu IAAF World Championships | Korea |

| 25 | (Min, 2020) | Correlational | 396 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, DI, SA, BI | Spectator | 2019 Gwangju FINA World Championships | Korea |

| 26 | Min and Lee (2019) | Correlational | 292 | PEQ, OQ, DI, BI | Athlete | 2017 Tour de Korea | Korea |

| 27 | H. Kim and Park (2008) | Correlational | 349 | PEQ, OQ, DI, SA | Spectator | Women’s Squash World Championships | Korea |

| 28 | Min and Woo (2023) | Correlational | 217 | PEQ, OQ, SA | Athlete | Korea Family Golf Challenge | Korea |

| 29 | J. Lee and Kim (2017) | Correlational | 286 | PEQ, OQ, DI, BI | Athlete | 2017 Cheongwon Saengsik Daecheongho Marathon | Korea |

| 30 | Seok and Cho (2020) | Correlational | 342 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA | Athlete | International Marathon Championship | Korea |

| 31 | (J. H. Park, 2011) | Correlational | 222 | PEQ, DI, SA | Athlete | National Badminton Championship | Korea |

| 32 | J. Kim and Kim (2024) | Correlational | 305 | PEQ, DI, SA | Athlete | Gangwon Province Youth Winter Olympics | Korea |

| 33 | (Ko, 2009) | Correlational | 363 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Athlete | The 18th Gyeongju Marathon | Korea |

| 34 | (Ji, 2011) | Correlational | 389 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Athlete | The 24th Olympic Day Marathon | Korea |

| 35 | Oh and Song (2020) | Correlational | 339 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, DI, BI | Athlete | Regional Marathon Championship | Korea |

| 36 | M. Kim and Lee (2018) | Correlational | 269 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA, BI | Spectator | U20 Gyeongju World Cup | Korea |

| 37 | J. Park and Park (2015) | Correlational | 274 | IQ, DI, BI | Spectator | 2014 National Elementary School Football Championship | Korea |

| 38 | (J. Lee, 2024) | Correlational | 300 | PEQ, OQ, IQ, SA | Spectator | Korea Ladies Professional Golf Tour | Korea |

| 39 | H. Park and Shin (2017) | Correlational | 382 | PEQ, IQ, SA, BI | Athlete | Ocean Sports Event | Korea |

| Effect Size and 95% Interval | Test of Null (2-Tail) | Heterogeneity | Publication Bias | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | K | N | Correlation | Lower | Upper | Z | p | Q(df) | p | I2 | Funnel | Egger’s | |

| PEQ-OQ | 26 | 11,430 | F | 0.523 | 0.510 | 0.537 | 61.911 | <0.001 | 771.55 | <0.001 | 96.76 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.530 | 0.452 | 0.600 | 11.257 | <0.001 | (25) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| PEQ-IQ | 22 | 8546 | F | 0.582 | 0.567 | 0.596 | 61.245 | <0.001 | 472.37 | <0.001 | 95.55 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.583 | 0.512 | 0.647 | 12.868 | <0.001 | (21) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| PEQ-DI | 11 | 3392 | F | 0.447 | 0.419 | 0.474 | 27.866 | <0.001 | 55.61 | <0.001 | 82.02 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.448 | 0.381 | 0.510 | 11.715 | <0.001 | (10) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| PEQ-SA | 21 | 8965 | F | 0.527 | 0.512 | 0.542 | 55.351 | <0.001 | 641.94 | <0.001 | 96.88 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.535 | 0.445 | 0.614 | 9.848 | <0.001 | (20) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| PEQ-BI | 24 | 10,108 | F | 0.446 | 0.430 | 0.461 | 48.003 | <0.001 | 345.31 | <0.001 | 93.34 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.455 | 0.393 | 0.514 | 12.570 | <0.001 | (23) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| OQ-IQ | 18 | 7587 | F | 0.573 | 0.558 | 0.588 | 56.573 | <0.001 | 714.08 | <0.001 | 97.62 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.564 | 0.455 | 0.656 | 8.505 | <0.001 | (17) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| OQ-DI | 10 | 3694 | F | 0.476 | 0.450 | 0.500 | 31.304 | <0.001 | 30.27 | <0.001 | 70.27 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.475 | 0.428 | 0.520 | 16.988 | <0.001 | (9) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| OQ-SA | 18 | 8195 | F | 0.525 | 0.509 | 0.540 | 52.600 | <0.001 | 946.89 | <0.001 | 98.21 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.543 | 0.418 | 0.648 | 7.303 | <0.001 | (17) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| OQ-BI | 23 | 10,443 | F | 0.462 | 0.447 | 0.477 | 50.967 | <0.001 | 838.19 | <0.001 | 97.38 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.486 | 0.390 | 0.572 | 8.722 | <0.001 | (22) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| IQ-DI | 7 | 2202 | F | 0.511 | 0.480 | 0.542 | 26.363 | <0.001 | 95.09 | <0.001 | 93.69 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.525 | 0.391 | 0.637 | 6.737 | <0.001 | (6) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| IQ-SA | 16 | 6121 | F | 0.532 | 0.513 | 0.549 | 46.172 | <0.001 | 714.86 | <0.001 | 97.90 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.554 | 0.421 | 0.663 | 6,933 | <0.001 | (15) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| IQ-BI | 21 | 7772 | F | 0.434 | 0.416 | 0.452 | 40.834 | <0.001 | 570.32 | <0.001 | 96.55 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.473 | 0.374 | 0.561 | 8.326 | <0.001 | (20) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| DI-SA | 7 | 2321 | F | 0.519 | 0.489 | 0.549 | 27.602 | <0.001 | 39.15 | <0.001 | 84.67 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.525 | 0.444 | 0.597 | 10.860 | <0.001 | (6) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| DI-BI | 13 | 4372 | F | 0.509 | 0.486 | 0.530 | 36.917 | <0.001 | 124.20 | <0.001 | 90.34 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.520 | 0.446 | 0.587 | 11.693 | <0.001 | (12) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| SA-BI | 14 | 6198 | F | 0.637 | 0.622 | 0.652 | 59.129 | <0.001 | 506.82 | <0.001 | 97.44 | S | >0.05 |

| R | 0.649 | 0.549 | 0.732 | 9.628 | <0.001 | (13) | S | >0.05 | |||||

| PEQ | OQ | IQ | DI | SA | BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEQ | 1 | |||||

| OQ | 0.530 *** | 1 | ||||

| IQ | 0.583 *** | 0.564 *** | 1 | |||

| DI | 0.448 *** | 0.475 *** | 0.525 *** | 1 | ||

| SA | 0.535 *** | 0.543 *** | 0.554 *** | 0.525 *** | 1 | |

| BI | 0.455 *** | 0.486 *** | 0.473 *** | 0.520 *** | 0.649 *** | 1 |

| 95% Confidence Intervals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Estimates | SE | Lbound | Ubound | z-Value | p-Value |

| PEQ-SA | 0.206 *** | 0.051 | 0.107 | 0.305 | 4.073 | <0.001 |

| OQ-SA | 0.207 ** | 0.065 | 0.080 | 0.334 | 3.194 | 0.001 |

| IQ-SA | 0.198 ** | 0.068 | 0.063 | 0.332 | 2.886 | 0.004 |

| DI-SA | 0.310 *** | 0.043 | 0.225 | 0.394 | 7.191 | <0.001 |

| SA-BI | 0.758 *** | 0.027 | 0.704 | 0.812 | 27.575 | <0.001 |

| Path Type | 95% Likelihood-Based CIs | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Lbound | Estimates | Ubound | ||

| Indirect Path | PEQ-SA-BI | 0.078 | 0.156 | 0.230 | Significant |

| Indirect Path | OQ-SA-BI | 0.057 | 0.157 | 0.251 | Significant |

| Indirect Path | IQ-SA-BI | 0.041 | 0.150 | 0.249 | Significant |

| Indirect Path | DI-SA-BI | 0.168 | 0.235 | 0.298 | Significant |

| Direct Path | PEQ-BI | −0.049 | 0.074 | 0.190 | Not Significant |

| Direct Path | OQ-BI | −0.049 | 0.111 | 0.261 | Not Significant |

| Direct Path | IQ-BI | −0.177 | 0.001 | 0.173 | Not Significant |

| Direct Path | DI-BI | 0.088 | 0.196 | 0.297 | Significant |

| Path | Estimates | Estimates | Free | Constraints | Δχ2 | Δdf | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event size | Large scale | Small scale | RMSEA = 0.018 | RMSEA = 0.018 | 37.191 | 10 | <0.05 |

| PEQ-SA | 0.189 ** | 0.233 *** | CFI = 0.995 | CFI = 0.988 | |||

| OQ-SA | 0.229 * | 0.097 | TLI = 0.981 | TLI = 0.980 | |||

| IQ-SA | 0.256 ** | 0.079 | SRMR = 0.049 | SRMR = 0.071 | |||

| DI-SA | 0.281 *** | 0.354 *** | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||

| Tourist | Spectator | Athlete | RMSEA = 0.017 | RMSEA = 0.013 | 15.630 | 10 | 0.111 |

| PEQ-SA | 0.194 * | 0.226 *** | CFI = 0.995 | CFI = 0.994 | |||

| OQ-SA | 0.250 * | 0.195 ** | TLI = 0.982 | TLI = 0.990 | |||

| IQ-SA | 0.239 * | 0.179 ** | SRMR = 0.052 | SRMR = 0.066 | |||

| DI-SA | 0.255 ** | 0.307 *** | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | |||

| Cultural | Eastern | Western | RMSEA = 0.015 | RMSEA = 0.012 | 16.769 | 10 | <0.05 |

| PEQ-SA | 0.159 * | 0.311 *** | CFI = 0.997 | CFI = 0.996 | |||

| OQ-SA | 0.186 * | 0.223 ** | TLI = 0.988 | TLI = 0.993 | |||

| IQ-SA | 0.217 ** | 0.233 * | SRMR = 0.048 | SRMR = 0.058 | |||

| DI-SA | 0.356 ** | 0.182 ** | p = 0.003 | p = 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, H.; Kim, D.; Kim, K. Verification of the Impact of Sports Event Service Quality and Host Destination Image on Sports Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions Through Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081019

Jia H, Kim D, Kim K. Verification of the Impact of Sports Event Service Quality and Host Destination Image on Sports Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions Through Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081019

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Hui, Daehwan Kim, and Kyungun Kim. 2025. "Verification of the Impact of Sports Event Service Quality and Host Destination Image on Sports Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions Through Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081019

APA StyleJia, H., Kim, D., & Kim, K. (2025). Verification of the Impact of Sports Event Service Quality and Host Destination Image on Sports Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions Through Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081019