Redefining Body-Self Relationships Through Outdoor Physical Activity: Experiences of Women Navigating Illness, Injury, and Disability

Abstract

1. Introduction

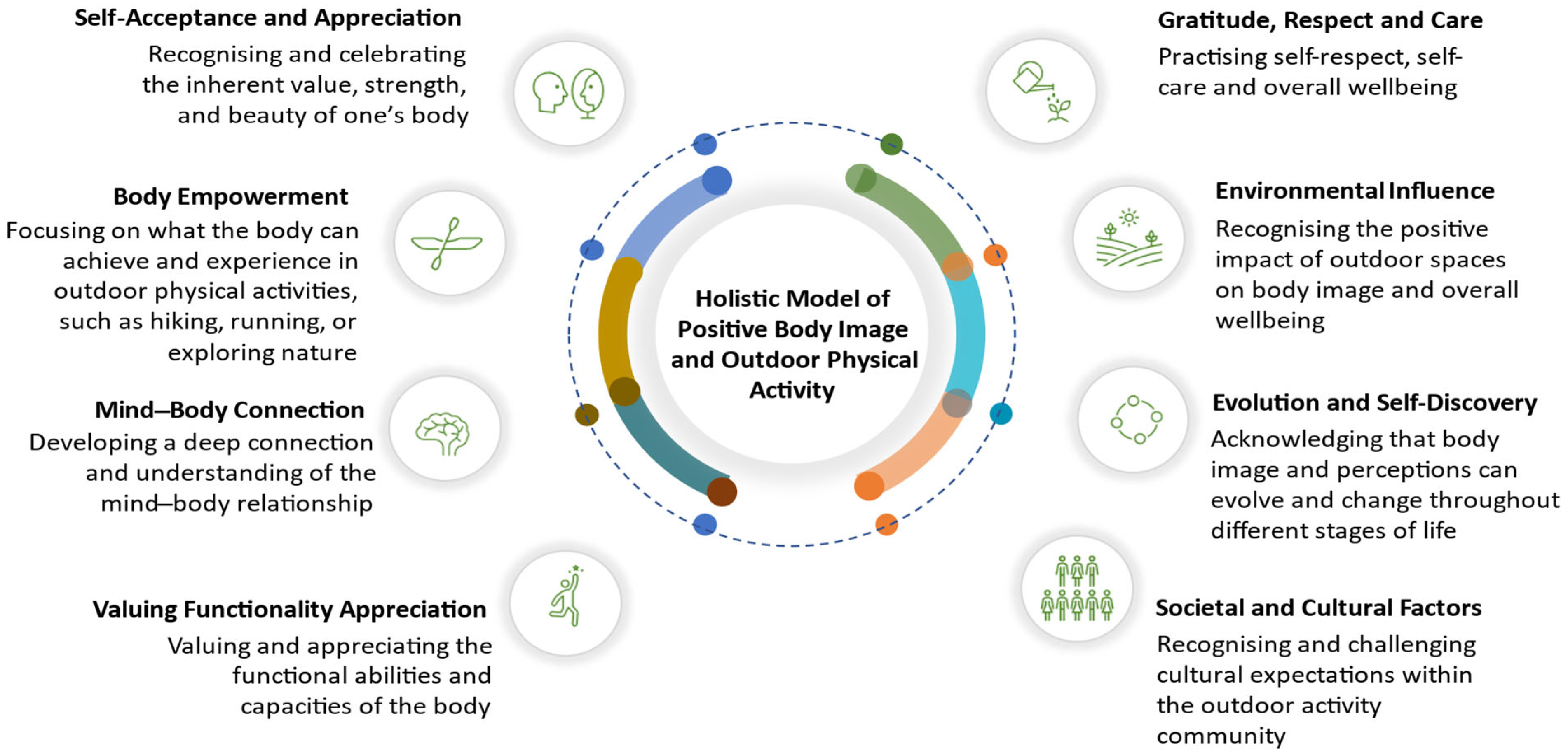

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Transformative Potential of Nature Immersion and Outdoor Physical Activity

2.2. Bodies, Narratives, and Identity During Physical Transitions

2.3. Reimagining Bodies in Outdoor Contexts: Beyond Deficit Models

2.4. Research Gaps and Current Study

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participant Characteristics

3.2.1. Sampling Limitations and Transferability Considerations

3.2.2. Condition Categories and Temporal Dimensions

3.3. Analytical Framework

3.3.1. Development of the Original Model

3.3.2. Theoretical Framework for Disability-Informed Reinterpretation

3.4. Data Analysis Procedures

3.5. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

3.6. Ethical Considerations

4. Findings: Bodies That Pause, Bodies That Persist

4.1. Personalized Redefinition of Functionality Transcending Standardized Metrics

4.1.1. Agency Through Embodied Expertise

“I have fibromyalgia so must exercise frequently and at moderate pace to keep healthy and avoid muscle flare ups and extreme fatigue. I’m incredibly grateful for what my body can do because I’ve seen the other side of the spectrum.”

4.1.2. Redefining What Function Means

“Post babies, I have a new perspective on my body. Having had a birth injury resulting in pelvic organ prolapse, I am mindful that my body does not function the same as it used to, but I’m also amazed at how I have adapted and can still do my favourite outdoor activity (mountain biking).”

“I’ve had reduced functionality following one total hip replacement and ahead of another. This has been frustrating and I’m still in a level of regular pain. Nonetheless I’m back outdoors regularly because being outdoors makes me happy, and I have less years ahead than I’ve had before so I need to get moving!!”

4.2. Therapeutic Engagement with Natural Environments Fostering Embodied Acceptance

4.2.1. Self-Acceptance as Ongoing Practice

“The last two years I have struggled more than usual—I was diagnosed with endometriosis which has led to weight gain but also to not being able to use my body in the ways I have done for most of my life. I get tired, and sore, and I’m scared of making things worse or over-exerting myself. I am sometimes angry at my body for not being the reliable friend it has always been.”

4.2.2. Enhanced Mind-Body Awareness

“I am very aware of what my body needs to function well, and I am more inclined to rest now rather than push through and cause injuries if I am not feeling the best. It has taken a long time for me to be content with the body I have been given. I am much kinder and engage in more low-impact activities, lots of massage, and recover now too.”

4.2.3. Nature as Therapeutic Landscape

“I underwent chemo and radiation ten years ago… I would go into radiation at 9:00 and then go to a trail he suggested… Although my body was sick and buttered by the intense treatment, being outside helped me regain my sense of self.”

4.3. Cyclical Reinforcement Between Physical Capability and Psychological Wellbeing

4.3.1. Gratitude Emerging Through Limitation

“Having MS, osteoporosis and T12 compression fracture, I’m grateful for anything my body allows me.” The phrase “anything my body allows me” reveals a shifted orientation—from body as possession to body as granting permission, from capabilities as rights to capabilities as gifts.

“My body has experienced a life-threatening illness, and as a result, it is quite different than it used to be. And yet, I can do all that I do, and my body enables me to do it. How could I not love it?”

4.3.2. Transformation Through Challenge

“My relationship has changed a lot with my body in the last 6 months. It’s really frustrating not to do the activities I want to, but I know my body is working hard to fight the fatigue and inflammation from covid. It’s still my friend, even if I’m disappointed in it!”

“For a period, I only had 20% vision and couldn’t drive (later this was resolved with surgery). It was an interesting experience. I found numerous ways to compensate and manage with poor vision. I found I didn’t miss my sight much, and I didn’t fear loss of sight, instead I found new ways of living opening up using all my other senses, and I learned to respect those with real disabilities much more.”

4.3.3. Community and Social Navigation

“I have a mixed relationship with my body’s capabilities. Sometimes I am amazed at what it can do and appreciate its strength and resilience. I do however have an autoimmune condition, so sometimes my body needs rest or isn’t capable of doing things some would perceive as everyday tasks. It is very up and down but overall I appreciate that I can still get out and do hikes etc. when I am well.”

“I am overweight and have various health issues but feel proud and empowered undertaking the vigorous activities I do. I love that people judge the way I look and are then surprised the level of fitness I have and what I can achieve.”

5. Discussion

5.1. Cyclical Rather than Linear: A Reconceptualized Model

5.2. Bodies Finding New Ways to Dwell

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions: Bodies That Transform

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A., & Filep, S. (2023). Positive psychology and tourism: Positive tourism. In Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research II: Enhancing the lives of tourists, residents of host communities and service providers (pp. 11–23). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Collinson, J. (2017). Breathing in life: Phenomenological perspectives on sport and exercise. In B. Smith, & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 11–23). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Alleva, J. M., & Tylka, T. L. (2021). Body functionality: A review of the literature. Body Image, 36, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alleva, J. M., Tylka, T. L., Van Oorsouw, K. M. I., Montanaro, E., Perey, I., Bolle, C., Boselie, J. J. L. M., Peters, M. L., & Webb, J. B. (2020). The effects of yoga on functionality appreciation and additional facets of positive body image. Body Image, 34, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacevičienė, M., Jankauskiene, R., & Swami, V. (2021). Nature exposure and positive body image: A cross-sectional study examining the mediating roles of physical activity, autonomous motivation, connectedness to nature, and perceived restorativeness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, K. A., Gammage, K. L., van Ingen, C., & Ditor, D. S. (2016). Managing the stigma: Exploring body image experiences and self-presentation among people with spinal cord injury. Health Psychology Open, 3(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitising concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G. N., Olvera-Alvarez, H. A., & Gross, J. J. (2021). The affective benefits of nature exposure. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(8), e12630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breault-Hood, J. (2023). Living in our bodies: The influence of outdoor physical activity on women’s positive body image [Doctoral dissertation, Western Sydney University]. Available online: https://researchers.westernsydney.edu.au/en/studentTheses/living-in-our-bodies (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Breault-Hood, J., Gray, T., Truong, S., & Ullman, J. (2017). Women and girls in outdoor education: Scoping the research literature and exploring prospects for future body image enquiry. Research in Outdoor Education, 15(1), 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. C., & Westaway, D. (2020). Mental health rescue effects of women’s outdoor tourism: A role in COVID-19 recovery. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 10304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caddick, N., Smith, B., & Phoenix, C. (2015). The effects of surfing and the natural environment on the well-being of combat veterans. Qualitative Health Research, 25(1), 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. (2002). Stories and silences: Disclosures and self in chronic illness. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(3), 302–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Zhao, C., & Li, C. (2024). Mental health and well-being in tourism: A Horizon 2050 paper. Tourism Review, 80(1), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, E. (2017). Brilliant imperfection: Grappling with cure. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, V. A. (2016). Women’s changing experiences of the home and life inside it after becoming chronically ill. In V. Chouinard, E. Hall, & R. Wilton (Eds.), Towards enabling geographies: ‘Disabled’ bodies and minds in society and space (pp. 45–61). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2011). Misfits: A feminist materialist disability concept. Hypatia, 26(3), 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K. Q. (2011). Feminist disability studies. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, J. (2008). Secondary analysis of qualitative data: An overview. Historical Social Research, 33(3), 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendren, S. (2020). What can a body do?: How we meet the built world. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Houge Mackenzie, S., Hodge, K., & Filep, S. (2021). How does adventure sport tourism enhance wellbeing? A conceptual model. Tourism Recreation Research, 48, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskiene, R., Urmanavicius, D., & Baceviciene, M. (2022). Association between motivation in physical education and positive body image: Mediating and moderating effects of physical activity habits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laurendeau, J., Higham, T., & Peers, D. (2020). Mountain Equipment Co-Op, “diversity work,” and the “inclusive” politics of erasure. Sociology of Sport Journal, 38(2), 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, S. (2021). Building resilience through trail running—Women’s perspectives. Leisure/Loisir, 45(3), 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Ginis, K. A., Bassett-Gunter, R. L., & Conlin, C. (2012). Body image and exercise. In E. O. Acevedo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of exercise psychology (pp. 55–75). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitten, D., & D’Amore, C. (2017). The relationship of women’s body image and experience in nature. In D. A. Vakoch, & S. Mickey (Eds.), Women and nature: Beyond dualism in gender, body, and the environment (pp. 96–116). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, P., & Dyck, I. (2003). Women, body, illness: Space and identity in the everyday lives of women with chronic illness. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Newbery, L. (2003). Will any/body carry that canoe? A geography of the body, ability, and gender. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 8(1), 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Papathomas, A., Williams, T. L., & Smith, B. (2015). Understanding physical activity participation in spinal cord injured populations: Three narrative types for consideration. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 10(1), 27295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pini, B., & Soldatic, K. (2012). Women, chronic illness, and rural Australia: Exploring the intersections between space, identity, and the body. In B. Leipert, B. Leach, & W. Thurston (Eds.), Rural women’s health (pp. 385–402). University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piran, N. (2017). Journeys of embodiment at the intersection of body and culture: The developmental theory of embodiment. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piran, N., & Teall, T. (2012). The developmental theory of embodiment. In Preventing eating-related and weight-related disorders: Collaborative research, advocacy, and policy change (pp. 169–198). Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G., Frost, J., & Frost, W. (2024). Exploring the benefits of outdoor activity participation in national parks: A case study of the Peak District National Park, England. Annals of Leisure Research, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G., Sand, M., May, C., & Farkić, J. (2025). Exploring the transformational role of regular nature-based adventure activity engagement in mental health and long-term eudaimonic well-being. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M. (2015). The bodymind problem and the possibilities of pain. Hypatia, 30(1), 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, C., Chandler, E., Harrison, E., Liddiard, K., & Ferrari, M. (2015). Project Re•Vision: Disability at the edges of representation. Disability & Society, 30(4), 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, C., Riley, S., LaMarre, A., & Bailey, K. A. (2021). What a body can do: Rethinking body functionality through a feminist materialist disability lens. Body Image, 38, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rygal, N., & Swami, V. (2021). Simulated nature and positive body image: A comparison of the impact of exposure to images of blue and green spaces. Body Image, 39, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaman, J., Sharp, E. H., McLaughlin, S., Tucker, C., VanGundy, K., & Rebellon, C. (2014). A longitudinal study of rural youth involvement in outdoor activities throughout adolescence: Exploring social capital as a factor in community-level outcomes. Research in Outdoor Education, 12(1), 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, V. (2018). Evaluating preexisting qualitative research data for secondary analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2013). Spinal cord injury, sport, and the narrative possibilities of posttraumatic growth. In P. Dasgupta, & R. K. Goel (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on disability and rehabilitation (pp. 133–156). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S., Aichinger, I., & Swami, V. (2022). The impact of nature exposure on body image and happiness: An experience sampling study. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 32(4), 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundgot-Borgen, C., Trangsrud, L. K. J., Otterbring, T., & Bratland-Sanda, S. (2022). Hiking, indoor biking, and body liking: A cross-sectional study examining the link between physical activity arenas and adults’ body appreciation. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V., Barron, D., & Furnham, A. (2018). Exposure to natural environments, and photographs of natural environments, promotes a more positive body image. Body Image, 24, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V., Barron, D., Hari, R., Grover, S., Smith, L., & Furnham, A. (2019). The nature of positive body image: Examining associations between nature exposure, self-compassion, functionality appreciation, and body appreciation. Ecopsychology, 11(4), 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V., Barron, D., Todd, J., Horne, G., & Furnham, A. (2020). Nature exposure and positive body image: (Re-)examining the mediating roles of connectedness to nature and trait mindfulness. Body Image, 34, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V., Barron, D., Weis, L., & Furnham, A. (2016). Bodies in Nature: Associations between exposure to nature, connectedness to nature, and body image in U.S. adults. Body Image, 18, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaac, A., Perrin, P. B., & Benotsch, E. G. (2018). Discrimination, mental health, and body image among transgender and gender-non-binary individuals: Constructing a multiple mediational path model. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 30(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. V., Warren-Findlow, J., Webb, J. B., Quinlan, M. M., Laditka, S. B., & Reeve, C. L. (2019). “It’s very valuable to me that I appear capable”: A qualitative study exploring relationships between body functionality and appearance among women with visible physical disabilities. Body Image, 30, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M. (2011). Sociocultural perspectives on human appearance and body image. In T. F. Cash, & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (2nd ed., pp. 12–19). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tylka, T. L., & Homan, K. J. (2015). Exercise motives and positive body image in physically active college women and men: Exploring an expanded acceptance model of intuitive eating. Body Image, 15, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, T. L., & Piran, N. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of positive body image and embodiment: Constructs, protective factors, and interventions. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, K. (1998). A call for race, gender, and class sensitive facilitation in outdoor experiential education. Journal of Experiential Education, 21(1), 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendell, S. (2001). Unhealthy disabled: Treating chronic illnesses as disabilities. Hypatia, 16(4), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. D. (2017). Reimagining disability and inclusive education through universal design for learning. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood-Barcalow, N. L., Tylka, T. L., & Augustus-Horvath, C. L. (2010). “But I like my body”: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2023). Disability and health. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 21 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Breault-Hood, J.; Gray, T.; Ullman, J.; Truong, S. Redefining Body-Self Relationships Through Outdoor Physical Activity: Experiences of Women Navigating Illness, Injury, and Disability. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081006

Breault-Hood J, Gray T, Ullman J, Truong S. Redefining Body-Self Relationships Through Outdoor Physical Activity: Experiences of Women Navigating Illness, Injury, and Disability. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081006

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreault-Hood, Joelle, Tonia Gray, Jacqueline Ullman, and Son Truong. 2025. "Redefining Body-Self Relationships Through Outdoor Physical Activity: Experiences of Women Navigating Illness, Injury, and Disability" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081006

APA StyleBreault-Hood, J., Gray, T., Ullman, J., & Truong, S. (2025). Redefining Body-Self Relationships Through Outdoor Physical Activity: Experiences of Women Navigating Illness, Injury, and Disability. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081006