Cross-Cultural Differences in Fear of Death, Emotional Intelligence, Coping with Death, and Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Comparative Study Between Spain and Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Population and Setting

2.3. Instruments and Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Nursing Education and Practice

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BFDS | Brief Fear of Death Scale |

| CD | Coping with Death |

| CDS | Coping with Death Scale |

| EI | Emotional Intelligence |

| ESP | Spain |

| FD | Fear of Death |

| MBI-SS | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Student Survey |

| PRT | Portugal |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TMMS-24 | Trait Meta-Mood Scale—24 ítems |

References

- Abram, M. D., & Jacobowitz, W. (2020). Resilience and burnout in healthcare students and inpatient psychiatric nurses: A between-groups study of two populations. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 35(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeschlimann, A., Heim, E., Killikelly, C., Arafa, M., & Maercker, A. (2024). Culturally sensitive grief treatment and support: A scoping review. SSM Mental Health, 5, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarboa, B. E., Pasay An, E., Dator, W. L. T., Alshammari, S. A., Mostoles, R., Uy, M. M., Alrashidi, N., Alreshidi, M. S., Mina, E., & Gonzales, A. (2022). Resilience and emotional intelligence of staff nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare, 10(11), 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida-Santos, K. K., Almeida-Mestre, G., Soares-Silva, J., Silva, M. G., Rosendo-Silva, R. A., & Souza-Silva, R. (2022). Comparison of the level of Fear of death among nursing and pedagogy students. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition), 32(6), 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alodhialah, A. M., Almutairi, A. A., & Almutairi, M. (2024). Exploring nurses’ emotional resilience and coping strategies in palliative and end-of-life care settings in saudi arabia: A qualitative study. Healthcare, 12(16), 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antão, C., Santos, B., Santos, N., Fernandes, H., Barroso, B., Oana, C., Mǎrginean, M., & Pimentel, H. (2025). Nursing degree curriculum: Differences and similarities between 15 European countries. Nursing Reports, 15(3), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aradilla-Herrero, A., Tomás-Sábado, J., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2013). Death attitudes and emotional intelligence in nursing students. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying, 66(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryuwat, P., Holmgren, J., Asp, M., Radabutr, M., & Lövenmark, A. (2024). Experiences of nursing students regarding challenges and support for resilience during clinical education: A qualitative study. Nursing Reports, 14(3), 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayed, A. (2025). The relationship between the emotional intelligence and clinical decision-making among nurses in neonatal intensive care units. SAGE Open Nursing, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belak, R. M., & Goh, K. H. (2024). Death anxiety and religiosity in a multicultural sample: A pilot study examining curvilinearity, age and gender in Singapore. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1398620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarneiro, A. P. F., & Gomes, S. M. R. (2015). Translation and validation of the coping with death scale: A study with nurses. Revista de Enfermagem Referencia, 4(7), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, R. d. D., Romero, B. B., de Matos, F. A., Costa, E., Espinha, D. C. M., Tomasso, C. de S., Lucchetti, A. L. G., & Lucchetti, G. (2018). Opinions and attitudes on the relationship between spirituality, religiosity and health: A comparison between nursing students from Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(13–14), 2804–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronado-Maldonado, I., & Benítez-Márquez, M. D. (2023). Emotional intelligence, leadership, and work teams: A hybrid literature review. Heliyon, 9(10), e20356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cybulska, A. M., Żołnowska, M. A., Schneider-Matyka, D., Nowak, M., Starczewska, M., Grochans, S., & Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. (2022). Analysis of nurses’ attitudes toward patient death. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, J. A., Campos, B., João, I., & Ii, M. (2012). Maslach burnout inventory—Student survey: Portugal-brazil cross-cultural adaptation. Revista de Saúde Pública, 46(5), 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugué, M., Sirost, O., & Dosseville, F. (2021). A literature review of emotional intelligence and nursing education. Nurse Education in Practice, 54, 103124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P., Katsiroumpa, A., Moisoglou, I., Derizioti, K., Gallos, P., Kalogeropoulou, M., & Papanikolaou, V. (2024). Emotional intelligence as critical competence in nurses’ work performance: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare, 12(19), 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiana, L., & Oliver, A. (2017). Confirmatory validation of the coping with death scale in palliative care professionals. Medicina Paliativa, 24(3), 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. D. L., De Abreu, L. C., Ramos, J. L. S., De Castro, C. F. D., Smiderle, F. R. N., Dos Santos, J. A., & Bezerra, I. M. P. (2019). Influence of burnout on patient safety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina, 55(9), 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, R., Custodio, J. B., Abal, F. J. P., González, R., Custodio, J. B., & Abal, F. J. P. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas del trait meta-mood scale-24 en estudiantes universitarios argentinos. Psicogente, 23(44), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Velando-Soriano, A., Martos-Cabrera, M. B., Cañadas, G. R., Albendín-García, L., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., & Aguayo-Estremera, R. (2023). Evolution and treatment of academic burnout in nursing students: A systematic review. Healthcare, 11(8), 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gysels, M., Evans, N., Meñaca, A., Andrew, E., Toscani, F., Finetti, S., Pasman, H. R., Higginson, I., Harding, R., & Pool, R. (2020). Culture and end of life care: A scoping exercise in seven European countries. In The ethical challenges of emerging medical technologies (pp. 335–350). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P., Duan, X., Jiang, J., Zeng, L., Zhang, P., & Zhao, S. (2022). Experience in the development of nurses’ personal resilience: A meta-synthesis. Nursing Open, 10(5), 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, I., Brooten, D., Youngblut, J. A. M., Roche, R., Li, J., & Hinds, A. M. (2020). Practices following the death of a loved one reported by adults from 14 countries or cultural/ethnic group. Nursing Open, 8(1), 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E., & Kim, J. (2022). Factors affecting academic burnout of nursing students according to clinical practice experience. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabeen, S., Khan, Z. H., & Mursaleen, M. (2024). Exploring the relationship between emotional intelligence and resilience: A clinical psychological perspective. Bulletin of Business and Economics (BBE), 13(1), 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzler, A. M., Helmreich, I., Chmitorz, A., König, J., Binder, H., Wessa, M., & Lieb, K. (2020). Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare professionals. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(7), CD012527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., Querido, A., Marques, G., Silva, M., Simões, D., Gonçalves, L., & Figueiredo, R. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and its psychological impact among healthy Portuguese and Spanish nursing students. Health Psychology Research, 9(1), 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisai-Goldstein, Y., & Shaulov, A. (2024). Medical students’ experience of a patient’s death and their coping strategies: A narrative literature review. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestro-González, A., Zuazua-Rico, D., Villalgordo-García, S., Mosteiro-Díaz, M. P., & Sánchez-Zaballos, M. (2025). Fear and attitudes toward death in nursing students: A longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today, 145, 106486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Parrilla, M. Á., Durán-Gómez, N., López-Jurado, C. F., Montanero-Fernández, J., & Cáceres, M. C. (2025). Impact of simulation-based learning experiences on enhancing coping with death in nursing students: An experimental study. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 103, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsivais, D. B., & Nunez, F. (2022). Simulation to develop teaching competencies in health professions educators: A Scoping review. Nursing Education Perspectives, 43(2), 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabirye, A. K., Munabi, I. G., Mubuuke, A. G., & Kiguli, S. (2025). Emotional and psychological experiences of nursing students caring for dying patients: An explorative study at a national referral hospital in Uganda. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagle, E., Griskevica, I., Rajevska, O., Ivanovs, A., Mihailova, S., & Skruzkalne, I. (2024). Factors affecting healthcare workers burnout and their conceptual models: Scoping review. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, A., Neto, F., Costa, P., & Gomes, M. J. (2025). Validation of the collett-lester fear of death scale with Portuguese students. Current Psychology, 44(8), 7024–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-De la Cruz, S. (2021). Attitudes of health science students towards death in Spain. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 27(8), 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Jurado, M. D. M. M., Márquez, M. D. M. S., Ruiz, N. F. O., & Linares, J. J. G. (2020). Validation of the maslach burnout inventory-student survey in Spanish adolescents. Psicothema, 32(3), 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prosen, M. (2022). Nursing students’ perception of gender-defined roles in nursing: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queirós, M. M., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., Carral, J. M. C., & Queirós, P. S. (2005). Validação e fiabilidade da versão portuguesa modificada da Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Revista de Psicologia, Educação e Cultura, 9, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir, A. E. (2018). Emotional intelligence in professional nursing practice: A concept review using Rodgers’s evolutionary analysis approach. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 5(2), 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodeles, S. C., Javier, F., Sánchez, M., & Martínez-Sellés, M. (2025). Physician and medical student burnout, a narrative literature review: Challenges, strategies, and a call to action. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, P. M., Scanes, E., & Locke, W. (2023). Stress adaptation and resilience of academics in higher education. Asia Pacific Education Review, 25(4), 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, S., & Au-Yong-oliveira, M. (2021). Student burnout: A case study about a Portuguese Public University. Education Sciences, 11(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tating, D. L. R. P., Tamayo, R. L. J., Melendres, J. C. N., Chin, I. K., Gilo, E. L. C., & Nassereddine, G. (2023). Effectiveness of interventions for academic burnout among nursing students: A systematic review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 20(2), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Jamovi Project. (2022). jamovi (version 2.3). [computer software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Tomás-Sábado, J., Limonero, J. T., & Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2007). Spanish adaptation of the collett-lester fear of death scale. Death Studies, 31(3), 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visiers-Jiménez, L., Palese, A., Brugnolli, A., Cadorin, L., Salminen, L., Leino-Kilpi, H., Löyttyniemi, E., Nemcová, J., Simão de Oliveira, C., Rua, M., Zeleníková, R., & Kajander-Unkuri, S. (2022). Nursing students’ self-directed learning abilities and related factors at graduation: A multi-country cross-sectional study. Nursing Open, 9(3), 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visiers-Jiménez, L., Suikkala, A., Salminen, L., Leino-Kilpi, H., Löyttyniemi, E., Henriques, M. A., Jiménez-Herrera, M., Nemcová, J., Pedrotti, D., Rua, M., Tommasini, C., Zeleníková, R., & Kajander-Unkuri, S. (2021). Clinical learning environment and graduating nursing students’ competence: A multi-country cross-sectional study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 23(2), 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, C., Arias-Gundín, O., & Rodríguez, C. (2019). Exploring coping and optimism as predictors of academic burnout and performance among university students. Educational Psychology, 39(6), 768–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F. M. F. (2025). Fostering caring attributes to improve patient care in nursing through small-group work: Perspectives of students and educators. Nursing Reports, 15(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y., & Wang, Q. (2019). Culture in emotional development. In Handbook of emotional development (pp. 569–593). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, S. Q., Wang, W., Seah, A. C. W., Kumar, N., Gan, J. O. N., Schmidt, L. T., Lin, Y., & Zhang, H. (2023). Nursing students’ experiences with patient death and palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Nurse Education in Practice, 69, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahran, Z., Hamdan, K. M., Hamdan-Mansour, A. M., Allari, R. S., Alzayyat, A. A., & Shaheen, A. M. (2021). Nursing students’ attitudes towards death and caring for dying patients. Nursing Open, 9(1), 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Gender | N (%) | p-Value | Mean Age (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESP | Male | 21 (19.63) | 0.293 | 20.86 (2.35) | 0.255 |

| Female | 86 (80.37) | 21.88 (4.22) | |||

| Total | 107 (100) | 21.68 (3.93) | |||

| PRT | Male | 9 (13.43) | 21.67 (4.89) | ||

| Female | 58 (86.57) | 21.08 (4.12) | |||

| Total | 67 (100) | 21.13 (4.22) |

| MeanESP (SD) | MeanPRT (SD) | Mean Difference | t-Test | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collett–Lester’s BFDS | |||||

| Fear of One’s Own Death | 2.95 (0.96) | 2.88 (1.09) | −0.069 | Mann-Whitney U a | 0.647 |

| Fear of the One’s Dying | 3.21 (0.90) | 3.07 (1.10) | −0.145 | Mann-Whitney U a | 0.408 |

| Fear of Death of Others | 3.64 (0.76) | 3.41 (0.88) | −0.226 | Mann-Whitney U a | 0.088 |

| Fear of the Dying of Others | 3.35 (0.71) | 3.35 (0.97) | 0.003 | Welch’s t b | 0.985 |

| TMMS-24 | |||||

| Emotional attention | 28.81 (4.95) | 28.90 (6.79) | 0.082 | Mann-Whitney U a | 0.587 |

| Emotional clarity | 28.03 (6.64) | 26.57 (6.61) | −1.461 | Student’s t | 0.159 |

| Emotional repair | 27.50 (5.65) | 28.00 (6.30) | 0.505 | Student’s t | 0.584 |

| Bugen’s CDS | |||||

| Coping with death | 109.34 (23.25) | 119.96 (25.85) | 10.619 | Welch’s t b | 0.007 |

| MBI-SS | |||||

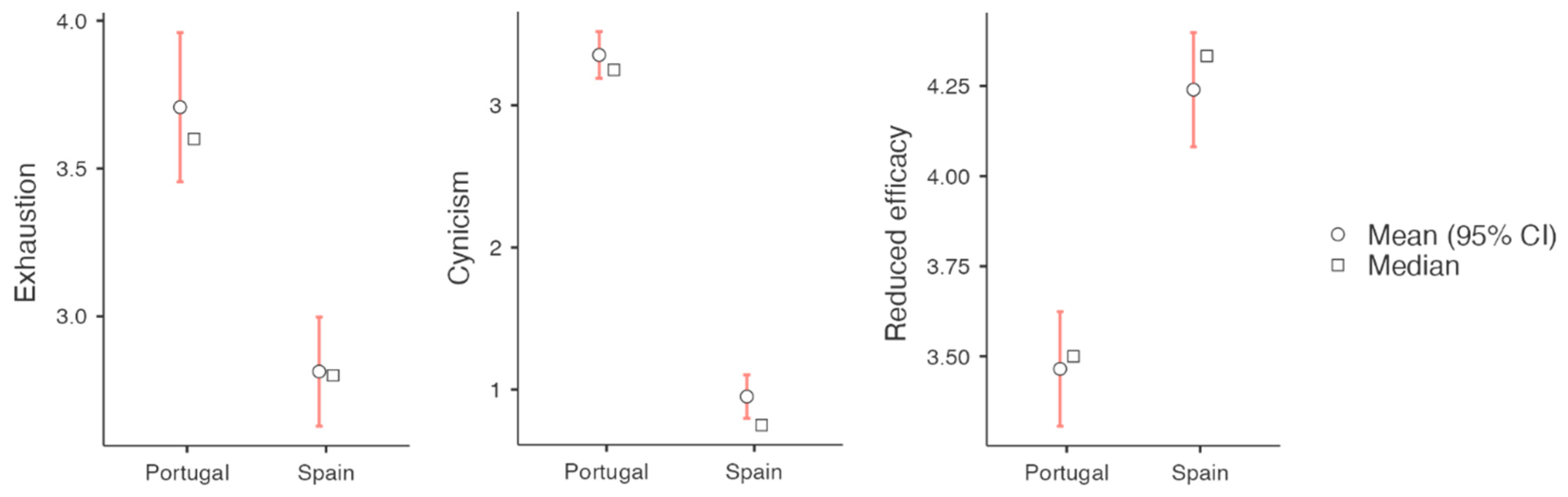

| Exhaustion | 2.81 (0.97) | 3.71 (1.06) | 0.894 | Student’s t | <0.001 |

| Cynicism | 0.95 (0.81) | 3.35 (0.69) | 2.404 | Mann-Whitney U a | <0.001 |

| Reduced efficacy | 4.24 (0.84) | 3.47 (0.66) | −0.775 | Mann-Whitney U a | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín-Parrilla, M.Á.; Durán-Gómez, N.; Marques, M.d.C.; López-Jurado, C.F.; Goes, M.; Cáceres, M.C. Cross-Cultural Differences in Fear of Death, Emotional Intelligence, Coping with Death, and Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Comparative Study Between Spain and Portugal. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070993

Martín-Parrilla MÁ, Durán-Gómez N, Marques MdC, López-Jurado CF, Goes M, Cáceres MC. Cross-Cultural Differences in Fear of Death, Emotional Intelligence, Coping with Death, and Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Comparative Study Between Spain and Portugal. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):993. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070993

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín-Parrilla, Miguel Ángel, Noelia Durán-Gómez, Maria do Céu Marques, Casimiro Fermín López-Jurado, Margarida Goes, and Macarena C. Cáceres. 2025. "Cross-Cultural Differences in Fear of Death, Emotional Intelligence, Coping with Death, and Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Comparative Study Between Spain and Portugal" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070993

APA StyleMartín-Parrilla, M. Á., Durán-Gómez, N., Marques, M. d. C., López-Jurado, C. F., Goes, M., & Cáceres, M. C. (2025). Cross-Cultural Differences in Fear of Death, Emotional Intelligence, Coping with Death, and Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Comparative Study Between Spain and Portugal. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070993