The Protective Role of Caring Parenting Styles in Adolescent Bullying Victimization: The Effects of Family Function and Constructive Conflict Resolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Caring Parenting Styles and Bullying

1.2. The Role of Family Functioning and Constructive Conflict Resolution

1.3. Current Study

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measures

2.1.3. Data Analysis

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Common Method Bias Test

2.2.2. Current Status of Adolescent Bullying Victimization

2.2.3. Relationship Between Caring Parenting Style and Adolescent Bullying Victimization

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Data Analysis

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2.2. Descriptive Statistics Results

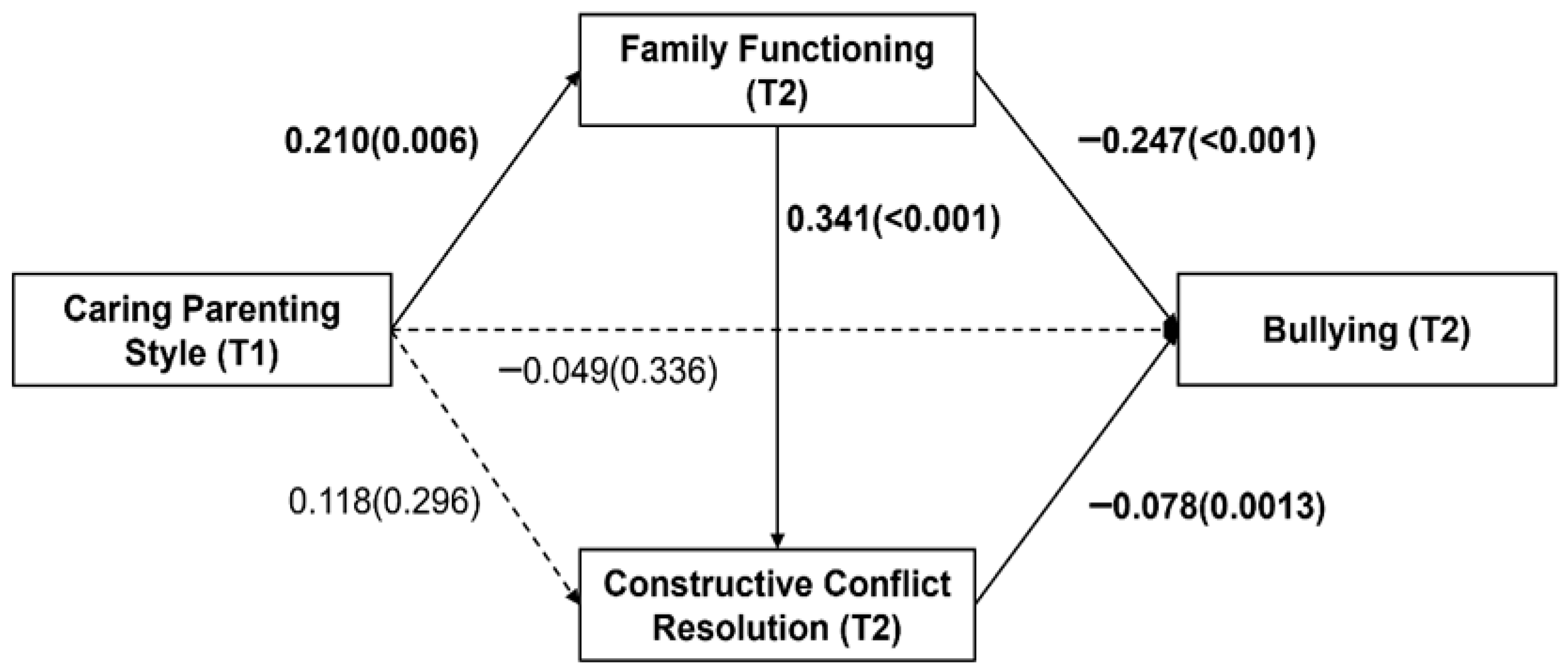

3.2.3. Chain Mediation Model Results

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boele, S., Van der Graaff, J., de Wied, M., Van der Valk, I. E., Crocetti, E., & Branje, S. (2019). Linking parent–child and peer relationship quality to empathy in adolescence: A multilevel meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(6), 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borualogo, I. S., Varela, J. J., & de Tezanos-Pinto, P. (2025). Sibling and school bullying victimization and its relation with children’s subjective well-being in indonesia: The protective role of family and school climate. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 40(5–6), 1433–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boterhoven de Haan, K. L., Hafekost, J., Lawrence, D., Sawyer, M. G., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). Reliability and validity of a short version of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster family assessment device. Family Process, 54(1), 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowers, E. P., Johnson, S. K., Buckingham, M. H., Gasca, S., Warren, D. J. A., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Important non-parental adults and positive youth development across mid- to late-adolescence: The moderating effect of parenting profiles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(6), 897–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozoglan, B., & Kumar, S. (2022). Parenting styles, parenting stress and hours spent online as predictors of child internet addiction among children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(10), 4375–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braswell, H., & Kushner, H. I. (2012). Suicide, social integration, and masculinity in the U.S. military. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butovskaya, M. L., Timentschik, V. M., & Burkova, V. N. (2007). Aggression, conflict resolution, popularity, and attitude to school in Russian adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 33(2), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, A., Runions, K., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Romera, E. M. (2023). Bullying and cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: Prospective within-person associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(2), 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X., Lu, J., Ran, H., Che, Y., Fang, D., Chen, L., Peng, J., Wang, S., Liang, X., Sun, H., & Xiao, Y. (2022). Resilience mediates parenting style associated school bullying victimization in Chinese children and adolescents. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X., & Chen, Z. (2024). The associations between parenting and bullying among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 54(4), 928–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonnesi, C., Draijer, E. M., Jan J. M. Stams, G., Van der Bruggen, C. O., Bögels, S. M., & Noom, M. J. (2011). The relation between insecure attachment and child anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnic, K. A. (2024). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: Developmental psychopathology perspectives. Development and Psychopathology, 36(5), 2369–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, C., Shuang-Zi, L., Cheng, W.-J., & Wang, T. (2022). Mediating effects of coping styles on the relationship between family resilience and self-care status of adolescents with epilepsy transitioning to adult healthcare: A cross-sectional study in China. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 63, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological Science, 25(1), 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doty, J. L., Gower, A. L., Rudi, J. H., McMorris, B. J., & Borowsky, I. W. (2017). Patterns of bullying and sexual harassment: Connections with parents and teachers as direct protective factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(11), 2289–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, D. L., Van Ryzin, M. J., & Holt, M. K. (2018). Trajectories of bully perpetration across early adolescence: Static risk factors, dynamic covariates, and longitudinal outcomes. Psychology of Violence, 8(2), 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, E., Torresani, S., & Zimmermann, C. (2001). Further results on the reliability of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in an Italian sample of schizophrenic patients and their parents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, E. D., Sharkey, J. D., Green, J. G., Furlong, M. J., & Tanigawa, D. (2011). Getting precise and pragmatic about the assessment of bullying: The development of the California Bullying Victimization Scale. Aggressive Behavior, 37(3), 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, C. E., Horwitz, A., Thomas, A., Opperman, K., Gipson, P., Burnside, A., Stone, D. M., & King, C. A. (2017). Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, R., Loios, S., & Pedro, M. (2016). Family functioning and adolescent psychological maladjustment: The mediating role of coping strategies. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47(5), 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grusec, J. E. (2011). Socialization processes in the family: Social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoagwood, K. E., Cavaleri, M. A., Serene Olin, S., Burns, B. J., Slaton, E., Gruttadaro, D., & Hughes, R. (2010). Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, C., Liu, Z., Gao, L., Jin, Y., Shi, J., Liang, R., Maimaitiming, M., Ning, X., & Luo, Y. (2022). Global trends and regional differences in the burden of anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder attributed to bullying victimisation in 204 countries and territories, 1999–2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 31, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J. S., Lee, C.-H., Lee, J., Lee, N. Y., & Garbarino, J. (2014). A review of bullying prevention and intervention in south korean schools: An application of the social–ecological framework. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45(4), 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B. (2021). Is bullying victimization in childhood associated with mental health in old age. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(1), 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H., Ding, Y., Liang, Y., Zhang, Y., Peng, Q., Wan, X., & Chen, C. (2022). The mediating effects of coping style and resilience on the relationship between parenting style and academic procrastination among Chinese undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, V., DiMillo, J., & Koszycki, D. (2020). Psychometric properties of the parental bonding instrument in a sample of canadian children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 51(5), 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvonen, J., & Graham, S. (2014). Bullying in schools: The power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanovic, S., & Skoog, T. (2021). The role of the family’s emotional climate in the links between parent-adolescent communication and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(2), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, V. (2015). Bullying among school-age children in the greater Beirut area: Risk and protective factors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, M., Seyedi Asl, S. T., Nazari Anamag, A., SabzehAra Langaroudi, M., Moharami, J., Ahmadi, S., Ganjali, A., Ghiasi, Z., Nafeli, M., & Kasaeiyan, R. (2023). Parenting styles, maladaptive coping styles, and disturbed eating attitudes and behaviors: A multiple mediation analysis in patients with feeding and eating disorders. PeerJ, 11, e14880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S., Choi, H., Park, M.-H., & Park, B. (2024). Differential role of negative and positive parenting styles on resting-state brain networks in middle-aged adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 365, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C., Yuan, L., Lin, W., Zhou, Y., & Pan, S. (2017). Depression and resilience mediates the effect of family function on quality of life of the elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 71, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in is research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, S., Canário, C., Cristina Gugliandolo, M., Merkas, M., & Keijsers, L. (2020). Family functioning and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems: Disentangling between-, and within-family associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matejevic, M., Jovanovic, D., & Lazarevic, V. (2014). Functionality of family relationships and parenting style in families of adolescents with substance abuse problems. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 128, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Rom, E. (2011). The effects of implicit and explicit security priming on creative problem solving. Cognition and Emotion, 25(3), 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milevsky, A., Schlechter, M., Netter, S., & Keehn, D. (2007). Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(1), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbuchi, K., Chiba, S., & Fukushima, O. (1996). Mitigation of interpersonal conflicts: Politeness and time pressure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(10), 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österman, K., Björkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K. M. J., Landau, S. F., Fraczek, A., & Pastorelli, C. (1997). Sex differences in styles of conflict resolution: A developmental and cross-cultural study with data from Finland, Israel, Italy, and Poland. In Cultural variation in conflict resolution. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G. (1990). The parental bonding instrument. A decade of research. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 25(6), 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poland-McClain, W., Rai, A., Archdeacon, N., Shallal, G., Mulanovich, G. S., & Tallman, P. (2024). Scoping Review of Cultural Responsivity in Interventions to Prevent Gender-Based Violence in Latin America. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, V., & Archbold, J. (1995). Development and application of social learning theory. British Journal of Nursing, 4(21), 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijntjes, A., Vermande, M., Goossens, F. A., Olthof, T., van de Schoot, R., Aleva, L., & van der Meulen, M. (2013). Developmental trajectories of bullying and social dominance in youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(4), 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbaum, F., Rosen, K., Ujiie, T., & Uchida, N. (2002). Family systems theory, attachment theory, and culture. Family Process, 41(3), 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeniuk, Y. Y., Brown, R. L., & Riesch, S. K. (2016). Analysis of the efficacy of an intervention to improve parent–adolescent problem solving. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38(7), 790–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieving, R. E., McRee, A.-L., McMorris, B. J., Shlafer, R. J., Gower, A. L., Kapa, H. M., Beckman, K. J., Doty, J. L., Plowman, S. L., & Resnick, M. D. (2017). Youth–adult connectedness: A key protective factor for adolescent health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(3), S275–S278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, A., & Holmes, J. (2019). Attachment and psychotherapy. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson-Hinde, J., & Akister, J. (1995). The McMaster model of family functioning: Observer and parental ratings in a nonclinical sample. Family Process, 34(3), 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niejenhuis, C., Huitsing, G., & Veenstra, R. (2020). Working with parents to counteract bullying: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve parent-school cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Salfate, S., Paez, D., Liu, J. H., Pratto, F., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2018). A comparison of social dominance theory and system justification: The role of social status in 19 nations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(7), 1060–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velotti, P., Rogier, G., Beomonte Zobel, S., Chirumbolo, A., & Zavattini, G. C. (2022). The relation of anxiety and avoidance dimensions of attachment to intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis about perpetrators. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(1), 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenmakers, E.-J., Marsman, M., Jamil, T., Ly, A., Verhagen, J., Love, J., Selker, R., Gronau, Q. F., Šmíra, M., Epskamp, S., Matzke, D., Rouder, J. N., & Morey, R. D. (2018). Bayesian inference for psychology. Part I: Theoretical advantages and practical ramifications. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(1), 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Wang, Y., Wang, G., Wilson, A., Jin, T., Zhu, L., Yu, R., Wang, S., Yin, W., Song, H., Li, S., Jia, Q., Zhang, X., & Yang, Y. (2021). Structural family factors and bullying at school: A large scale investigation based on a Chinese adolescent sample. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, X., Chen, F., Yuan, C., Zhang, X., Luo, Y., Xue, Y., & Wang, Y. (2018). The relationship between parental conflict and preschool children’s behavior problems: A moderated mediation model of parenting stress and child emotionality. Children and Youth Services Review, 95, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Zhen, R., Liu, Z., Wu, X., Xu, Y., Ma, R., & Zhou, X. (2023). Bullying victimization and comorbid patterns of PTSD and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Random intercept latent transition analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(11), 2314–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H., Han, T., Ma, S., Qu, G., Zhao, T., Ding, X., Sun, L., Qin, Q., Chen, M., & Sun, Y. (2022). Association of child maltreatment and bullying victimization among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of family function, resilience, and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H., Xu, Y., Wang, F., Jiang, J., Zhang, X., & Wang, X. (2015). Chinese adolescents’ coping tactics in a parent-adolescent conflict and their relationships with life satisfaction: The differences between coping with mother and father. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Male (n = 2278) | Female (n = 2299) | t | p | Cohen’s d | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.107 ± 1.1763 | 15.010 ± 1.750 | 1.864 | 0.062 | 0.055 | 0.188 |

| Verbal bullying | 1.406 ± 0.789 | 1.308 ± 0.682 | 4.498 | <0.001 | 0.133 | 781.405 |

| Physical bullying | 1.156 ± 0.525 | 1.070 ± 0.309 | 6.767 | <0.001 | 0.200 | 2.437 × 10+8 |

| Indirect bullying | 1.324 ± 0.721 | 1.269 ± 0.561 | 2.857 | 0.004 | 0.084 | 1.937 |

| Total bullying | 1.286 ± 0.576 | 1.204 ± 0.412 | 5.504 | <0.001 | 0.163 | 114,331.012 |

| Variable | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying | 1.245 ± 0.502 | — | |||

| Mother Caring | 2.096 ± 0.665 | −0.227 (<0.001) | — | ||

| Father Caring | 1.962 ± 0.712 | −0.183 (<0.001) | 0.550 (<0.001) | — | |

| Parental Caring | 2.029 ± 0.607 | −0.232 (<0.001) | 0.871 (<0.001) | 0.889 (<0.001) | — |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||||

| Caring T1 | 0.055 (0.344) | 1 | ||||||

| Family Functioning T1 | 0.098 (0.089) | 0.593 (<0.001) | 1 | |||||

| Constructive Conflict Resolution T1 | 0.103 (0.074) | 0.357 (<0.001) | 0.274 (<0.001) | 1 | ||||

| Bullying T1 | 0.075 (0.191) | −0.246 (<0.001) | −0.220 (<0.001) | −0.160 (0.005) | 1 | |||

| Family Functioning T2 | 0.133 (0.021) | 0.363 (<0.001) | 0.405 (<0.001) | 0.197 (0.001) | −0.031 (0.596) | 1 | ||

| Constructive Conflict Resolution T2 | 0.096 (0.096) | 0.283 (<0.001) | 0.241 (<0.001) | 0.402 (<0.001) | −0.121 (0.035) | 0.323 (<0.001) | 1 | |

| Bullying T2 | 0.062 (0.281) | −0.245 (<0.001) | −0.223 (<0.001) | −0.096 (0.095) | 0.186 (0.001) | −0.426 (<0.001) | −0.283 (<0.001) | 1 |

| M | — | 2.009 | 3.348 | 2.708 | 1.344 | 3.309 | 2.754 | 1.208 |

| SD | — | 0.580 | 0.620 | 0.978 | 0.477 | 0.649 | 0.980 | 0.441 |

| Outcome Variables | Predictor Variables | B | SE | t | p | 95%CI | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family functioning T2 | caring T1 | 0.210 | 0.075 | 2.796 | 0.006 | [0.062, 0.357] | 0.204 | 15.194 ** |

| gender | 0.107 | 0.068 | 1.567 | 0.118 | [−0.027, 0.241] | |||

| family functioning T1 | 0.302 | 0.068 | 4.433 | <0.001 | [0.168, 0.436] | |||

| constructive conflict resolution T1 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.994 | 0.321 | [−0.036, 0.110] | |||

| bullying T1 | 0.111 | 0.074 | 1.506 | 0.133 | [−0.034, 0.256] | |||

| constant | 1.574 | 0.239 | 6.580 | <0.001 | [1.103, 2.045] | |||

| Constructive conflict resolution T2 | family functioning T2 | 0.341 | 0.086 | 3.955 | <0.001 | [0.172, 0.511] | 0.232 | 14.829 ** |

| caring T1 | 0.118 | 0.112 | 1.047 | 0.296 | [−0.104, 0.340] | |||

| gender | 0.063 | 0.102 | 0.617 | 0.538 | [−0.137, 0.263] | |||

| family functioning T1 | 0.011 | 0.105 | 0.101 | 0.920 | [−0.195, 0.216] | |||

| constructive conflict resolution T1 | 0.320 | 0.055 | 5.782 | <0.001 | [0.211, 0.429] | |||

| bullying T1 | −0.096 | 0.110 | −0.875 | 0.382 | [−0.313, 0.120] | |||

| constant | 0.583 | 0.380 | 1.533 | 0.126 | [−0.027, 0.241] | |||

| Bullying T2 | constructive conflict resolution T2 | −0.078 | 0.026 | −2.972 | 0.003 | [−0.129, −0.026] | 0.241 | 13.358 ** |

| family functioning T2 | −0.247 | 0.040 | −6.232 | <0.001 | [−0.326, −0.169] | |||

| caring T1 | −0.049 | 0.051 | −0.965 | 0.336 | [−0.149, 0.051] | |||

| gender | 0.098 | 0.046 | 2.154 | 0.032 | [0.009, 0.188] | |||

| family functioning T1 | −0.032 | 0.014 | 0.047 | 0.027 | [−0.059, −0.004] | |||

| constructive conflict resolution T1 | 0.035 | 0.026 | 1.347 | 0.179 | [−0.016, 0.087] | |||

| bullying T1 | 0.133 | 0.049 | 2.684 | 0.008 | [0.035, 0.230] | |||

| constant | 2.009 | 0.171 | 11.737 | <0.001 | [1.672, 2.345] |

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot UlCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.116 | 0.055 | −0.223 | −0.008 |

| Direct effect | −0.049 | 0.051 | −0.149 | 0.051 |

| Total indirect effects | −0.067 | 0.038 | −0.154 | −0.010 |

| Path 1 1 | −0.052 | 0.029 | −0.117 | −0.007 |

| Path 2 2 | −0.009 | 0.011 | −0.034 | 0.008 |

| Path 3 3 | −0.006 | 0.005 | −0.019 | −0.0002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, H.; Fu, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Zhong, X. The Protective Role of Caring Parenting Styles in Adolescent Bullying Victimization: The Effects of Family Function and Constructive Conflict Resolution. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070982

Zhu H, Fu H, Liu H, Wang B, Zhong X. The Protective Role of Caring Parenting Styles in Adolescent Bullying Victimization: The Effects of Family Function and Constructive Conflict Resolution. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):982. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070982

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Haoliang, Haojie Fu, Haiyan Liu, Bin Wang, and Xiao Zhong. 2025. "The Protective Role of Caring Parenting Styles in Adolescent Bullying Victimization: The Effects of Family Function and Constructive Conflict Resolution" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070982

APA StyleZhu, H., Fu, H., Liu, H., Wang, B., & Zhong, X. (2025). The Protective Role of Caring Parenting Styles in Adolescent Bullying Victimization: The Effects of Family Function and Constructive Conflict Resolution. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 982. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070982