The Effects of Job Insecurity on Psychological Well-Being and Work Engagement: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Job Insecurity

2.2. Self-Efficacy at Work

2.3. Psychological Well-Being

2.4. Work Engagement

2.5. Perceived Supervisor Support

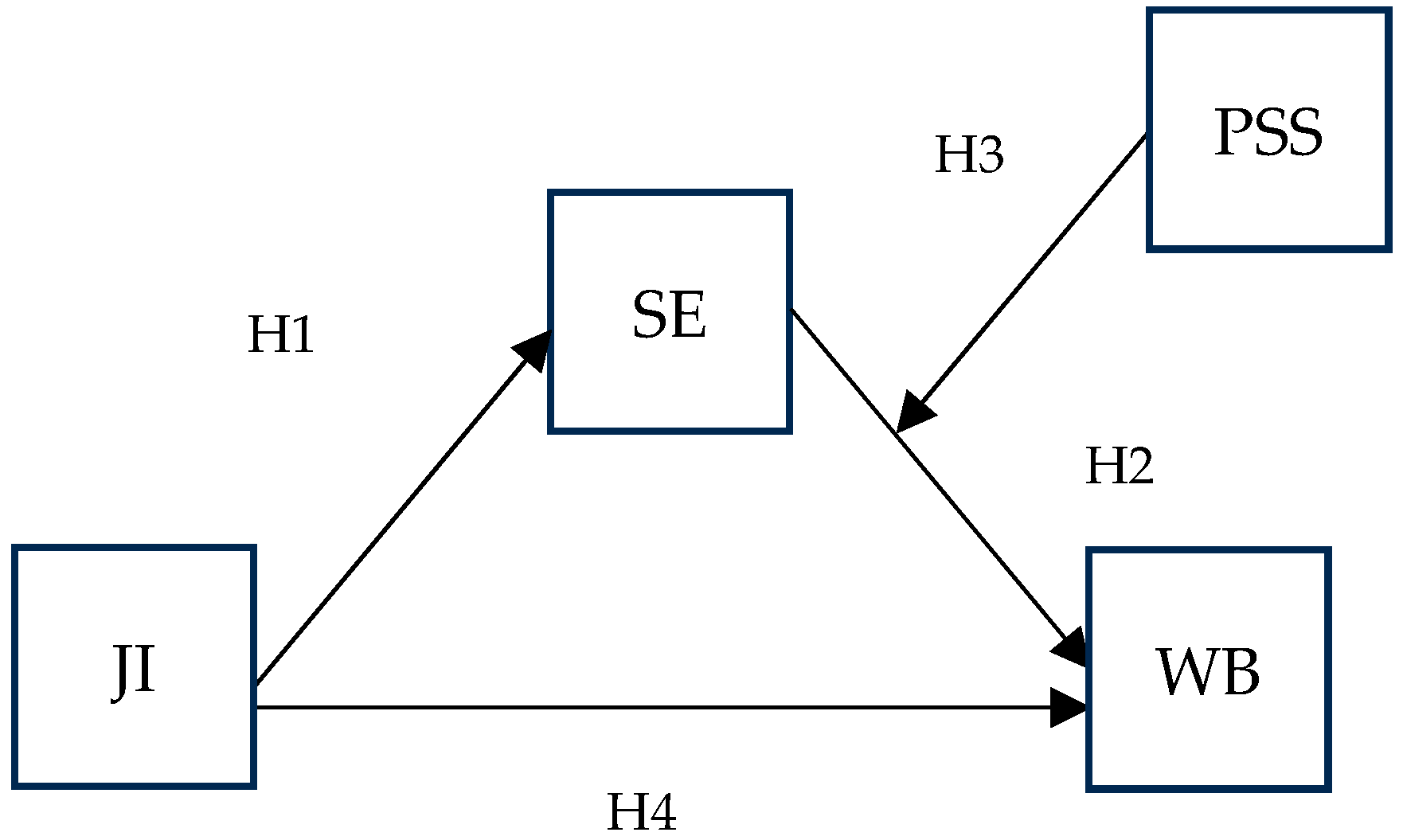

2.6. Research Model and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.2.1. Hypothesis Testing for Well-Being

4.2.2. Hypothesis Testing for Work Engagement

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Work

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdul Jalil, N. I., Tan, S. A., Ibharim, N. S., Musa, A. Z., Ang, S. H., & Mangundjaya, W. L. (2023). The relationship between job insecurity and psychological well-being among Malaysian precarious workers: Work–life balance as a mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, A. A., Adepoju, B., Garba, B. B., & Oscar, B. (2019). The Effect of self efficacy on perceived job insecurity in the nigerian banking industry: The mediating role of employee self esteem. Romanian Journal of Psychology, 21(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Airila, A., Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., Luukkonen, R., Punakallio, A., & Lusa, S. (2014). Are job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? The mediating role of work engagement. Work & Stress, 28(1), 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, S. J., Lee, C., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, cause, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32(4), 803–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Jensen, S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. (2003). Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands—Resources model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12(4), 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (pp. ix, 604). W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr, T. A., Bowling, N. A., & Bennett, M. M. (2010). Occupational stress and failures of social support: When helping hurts. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, J., Buitendach, J. H., & Rothman, S. (2005). Work locus of control and dispositional optimism as antecedents to job insecurity. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresó, E., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2011). Can a self-efficacy-based intervention decrease burnout, increase engagement, and enhance performance? A quasi-experimental study. Higher Education, 61(4), 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G., & Stinglhamber, F. (2014). The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. European Review of Applied Psychology, 64(5), 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D., & Branco, R. (2018). Liberalised dualisation. Labour market reforms and the crisis in Portugal: A new departure. European Journal of Social Security, 20(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroli, E., & Godard, M. (2016). Does job insecurity deteriorate health? Health Economics, 25(2), 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Castañeda, R., Vargas-Jiménez, E., Menéndez-Espina, S., & Medina-Centeno, R. (2023). Job insecurity and company behavior: Influence of fear of job loss on individual and work environment factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Westman, M., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2015). The commerce and crossover of resources: Resource conservation in the service of resilience. Stress and Health, 31(2), 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G. H. L., & Chan, D. K. S. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 272–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumbolo, A., & Areni, A. (2010). Job insecurity influence on job performance and mental health: Testing the moderating effect of the need for closure. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 31(2), 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumbolo, A., & Hellgren, J. (2003). Individual and organizational consequences of job insecurity: A European study. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 24(2), 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S., & Neves, P. (2017). Job insecurity and work outcomes: The role of psychological contract breach and positive psychological capital. Work & Stress, 31(4), 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Li, H., Xie, W., & Deng, T. (2022). Power distance belief and workplace communication: The mediating role of fear of authority. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M., Mazzetti, G., & Guglielmi, D. (2021). Job insecurity and job performance: A serial mediated relationship and the buffering effect of organizational justice. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debus, M. E., & Unger, D. (2017). The interactive effects of dual-earner couples’ job insecurity: Linking conservation of resources theory with crossover research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J., & Dormann, C. (2007). «Stressors, resources, and strain at work: A longitudinal test of the triple-match principle»: Correction to de Jonge and Dormann (2006). Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H. (2005). Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4), a200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H., Pienaar, J., & De Cuyper, N. (2016). Review of 30 years of longitudinal studies on the association between job insecurity and health and well-being: Is there causal evidence? Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H., Vander Elst, T., & De Cuyper, N. (2015). Job insecurity, health and well-being. In J. Vuori, R. Blonk, & R. H. Price (Eds.), Sustainable working lives (pp. 109–128). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Brizuela, R., Brenes-Leiva, G., Solís Salazar, M., & Torres-Carballo, F. (2017). Effects of power distance diversity within workgroups on work role performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Revista Tecnología en Marcha, 30, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Finstad, G. L., Bernuzzi, C., Setti, I., Fiabane, E., Giorgi, G., & Sommovigo, V. (2024). How is job insecurity related to workers’ work–family conflict during the pandemic? The mediating role of working excessively and techno-overload. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17(2), 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, R., Salanova, M., & Peiró, J. M. (2001). Moderator effects of self-efficacy on occupational stress. Psychology in Spain, 5(1), 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Greenglass, E. R., Burke, R. J., & Moore, K. A. (2003). Reactions to increased workload: Effects on professional efficacy of nurses. Applied Psychology, 52(4), 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. The Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, C., Scrima, F., Civilleri, A., & Salerno, L. (2018). The role of occupational self-efficacy in mediating the effect of job insecurity on work engagement, satisfaction and general health. Current Psychology, 37(3), 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Buckley, M. R. (2004). Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management, 30(6), 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarstrom, A., Virtanen, P., & Janlert, U. (2011). Are the health consequences of temporary employment worse among low educated than among high educated? The European Journal of Public Health, 21(6), 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, H., & Nordin, N. S. (2022). Perceived supervisor support and work engagement: Mediating role of job-related affective well-being. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 37(2), 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H. H. (1967). Modern factor analysis (2nd ed., revised). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books?id=6uk7DwAAQBAJ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Hämmig, O. (2017). Health and well-being at work: The key role of supervisor support. SSM-Population Health, 3, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, J., Sverke, M., & Isaksson, K. (1999). A two-dimensional approach to job insecurity: Consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1995). Multilevel research of human systems: Flowers, bouquets and gardens. Human Systems Management, 14(3), 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., & Lavaysse, L. M. (2018). Cognitive and affective job insecurity: A meta-analysis and a primary study. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2307–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiewitz, C., Restubog, S. L. D., Shoss, M. K., Garcia, P. R. J. M., & Tang, R. L. (2016). Suffering in silence: Investigating the role of fear in the relationship between abusive supervision and defensive silence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(5), 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., Siltaloppi, M., & Sonnentag, S. (2011). Job demands–resources model in the context of recovery: Testing recovery experiences as mediators. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(6), 805–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, C. J., Debus, M. E., Häusler, S., Lendenmann, N., & Kleinmann, M. (2010). Examining occupational self-efficacy, work locus of control and communication as moderators of the job insecurity—Job performance relationship. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 31(2), 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromydas, T., Thomson, R. M., Pulford, A., Green, M. J., & Katikireddi, S. V. (2021). Which is most important for mental health: Money, poverty, or paid work? A fixed-effects analysis of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. SSM-Population Health, 15, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2003). Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies (pp. 91–134). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1996). Consistency of the burnout construct across occupations. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 9(3), 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & Lepine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Bohle, S., Bal, P. M., Probs, T. M., Rofcanin, Y., & Munoz Medina, F. (2024). What do job insecure people do? Examining employee behaviors and their implications for well-being at a weekly basis. Journal of Management and Organization, 30, 1304–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2007). Emerging positive organizational behavior. Journal of Management, 33(3), 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. In Annual review of psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 397–422). Annual Reviews. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R. A., Pineault, L., & Hong, Y.-H. (2022). Normalizing the use of single-item measures: Validation of the single-item compendium for organizational psychology. Journal of Business and Psychology, 37(4), 639–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(1), 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, I. (2010). Measures of self-perceived well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(1), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mer, A., Virdi, A. S., & Sengupta, S. (2023). Unleashing the antecedents and consequences of work engagement in NGOs through the lens of JD-R model: Empirical evidence from India. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 34(4), 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabawanuka, H., & Ekmekcioglu, E. B. (2022). Millennials in the workplace: Perceived supervisor support, work–life balance and employee well–being. Industrial and Commercial Training, 54(1), 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K., & Smith, A. P. (2023). Psychosocial work conditions as determinants of well-being in Jamaican police officers: The mediating role of perceived job stress and job satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirani, E., & Salvini, S. (2015). Is temporary employment damaging to health? A longitudinal study on Italian workers. Social Science & Medicine, 124, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, T. M., Jiang, L., & Graso, M. (2016). Leader–member exchange: Moderating the health and safety outcomes of job insecurity. Journal of Safety Research, 56, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., Bakker, A. B., & Llorens, S. (2006). Flow at work: Evidence for an upward spiral of personal and organizational resources. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W. B., Xanthopoulou, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). The gain spiral of resources and work engagement: Sustaining a positive worklife. In Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (Vol. 1, pp. 118–131). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2013). What is engagement? In Employee engagement in theory and practice (pp. 15–35). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2008). 18 Enhancing work engagement through the management of human resources. In The individual in the changing working life (p. 380). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selenko, E., Mäkikangas, A., Mauno, S., & Kinnunen, U. (2013). How does job insecurity relate to self-reported job performance? Analysing curvilinear associations in a longitudinal sample. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M. K. (2017). Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamper, C. (2003). The impact of perceived organizational support on the relationship between boundary spanner role stress and work outcomes. Journal of Management, 29(4), 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, M., & Hellgren, J. (2002). The Nature of job insecurity: Understanding employment uncertainty on the brink of a new millennium. Applied Psychology, 51(1), 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, M., Låstad, L., Hellgren, J., Richter, A., & Näswall, K. (2019). A meta-analysis of job insecurity and employee performance: Testing Temporal aspects, rating source, welfare regime, and union density as moderators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T. W., & Kompier, M. (2003). Challenges in longitudinal designs in occupational health psychology. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Whoqol Group. (1998). The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science & Medicine, 46(12), 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üngüren, E., Onur, N., Demirel, H., & Tekin, Ö. A. (2024). The effects of job stress on burnout and turnover intention: The moderating effects of job security and financial dependency. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T., Cavents, C., Daneels, K., Johannik, K., Baillien, E., Van den Broeck, A., & Godderis, L. (2016). Job demands–resources predicting burnout and work engagement among Belgian home health care nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Outlook, 64(6), 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Ding, H. (2023). Strengths-based leadership and employee strengths use: The roles of strengths self-efficacy and job insecurity. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 39(1), 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Lu, C., & Siu, O. (2015). Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Jiang, H., Jin, W., Jiang, J., Liu, J., Guan, J., Liu, Y., & Bin, E. (2024). Examining the antecedents of novice STEM teachers’ job satisfaction: The roles of personality traits, perceived social support, and work engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, B., & Osberg, L. (2018). Job insecurity and mental health in Canada. Applied Economics, 50(38), 4137–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, H. D. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (1952). Constitution of the world health organization. In World Health Organization: Handbook of basic documents (pp. 3–20). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(1), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Obrenovic, B., Kamotho, D. W., Godinic, D., & Ostic, D. (2024). Enhancing job performance: The critical roles of well-being, satisfaction, and trust in supervisor. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X., Li, M., & Zhang, H. (2021). Suffering job insecurity: Will the employees take the proactive behavior or not? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 731162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D. Y. (2023). The hospitality stress matrix: Exploring job stressors and their effects on psychological well-being. Sustainability, 15(17), 13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 41.4 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Gender | 0.43 | - | - | 0.013 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. Tenure | 14.5 | 22.3 | - | 0.286 ** | 0.058 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4. Contract | 0.63 | - | - | 0.093 ** | −0.016 | 0.098 ** | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5. Job insecurity | 2.58 | 1.12 | - | 0.001 | 0.016 | −0.042 | −0.156 ** | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6. Self-efficacy | 4.23 | 0.75 | - | −0.035 | −0.063 * | −0.030 | 0.123 ** | −0.144 ** | - | - | - | - |

| 7. Supervisor support | 3.82 | 0.83 | 0.92 | −0.059 | −0.054 | −0.038 | 0.128 ** | −0.220 ** | 0.195 ** | - | - | - |

| 8. Work engagement | 3.89 | 0.73 | 0.78 | −0.076 * | −0.069 * | −0.045 | 0.129 ** | −0.208 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.464 ** | - | - |

| 9. Well-being | 3.36 | 0.89 | 0.90 | −0.138 ** | −0.013 | −0.019 | 0.093 ** | −0.240 ** | 0.302 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.532 ** | - |

| Variable | Well-Being | Work Engagement | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| 1. Age | −0.104 * | −0.099 * | −0.095 * | −0.067 * | −0.056 | −0.051 | −0.043 | −0.025 |

| 2. Gender | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.037 | 0.041 | −0.051 | −0.053 | −0.009 | −0.014 |

| 3. Tenure | 0.033 | 0.023 | 0.025 | 0.038 | −0.005 | −0.014 | −0.01 | −0.015 |

| 4. Contract | 0.121 *** | 0.082 * | 0.045 | 0.025 | 0.138 *** | 0.104 *** | 0.033 | 0.022 |

| 5. Job insecurity | −0.230 *** | −0.190 *** | −0.130 *** | −0.202 *** | −0.125 *** | −0.062 ** | ||

| 6. Self-efficacy | 0.282 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.540 *** | 0.491 *** | ||||

| 7. Supervisor Support | 0.335 *** | 0.347 *** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.076 | 0.156 | 0.260 | 0.028 | 0.065 | 0.346 | 0.457 |

| Δ R2 | 0.051 | 0.080 | 0.104 | 0.038 | 0.280 | 0.111 | ||

| F | 4.79 *** | 38.35 *** | 65.07 *** | 96.17 *** | 4.87 *** | 27.95 *** | 295.01 *** | 140.24 *** |

| Consequent | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy | Well-Being | ||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |

| Job insecurity (JI) | −0.099 | 0.021 | <0.001 | −0.106 | 0.023 | <0.001 | |

| Self-efficacy (SE) | - | - | - | 0.290 | 0.036 | <0.001 | |

| Supervisor support (SS) | - | - | - | 0.355 | 0.033 | <0.001 | |

| SE × SS | - | - | - | 0.120 | 0.039 | <0.001 | |

| R2 = 0.023 | R2 = 0.256 | ||||||

| F(1.872) = 20.610, p < 0.001 | F(4.869) = 74.964, p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Total, direct, and indirect effects of job insecurity on well-being | |||||||

| Effect | SE | p | |||||

| Total effect | −0.193 | 0.024 | <0.001 | ||||

| Direct effect | −0.161 | 0.024 | <0.001 | ||||

| Indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| Indirect effect (through self-efficacy) | −0.037 (0.039) | 0.009 | −0.059 | −0.021 | |||

| Conditional direct effects of self-efficacy on well-being | |||||||

| Moderator: Supervisor support | Effect | p | |||||

| −1 SD | 0.19 | <0.001 | |||||

| Mean | 0.29 | <0.001 | |||||

| +1 SD | 0.39 | <0.005 | |||||

| Conditional indirect effects of job insecurity on well-being | |||||||

| Moderator: Supervisor support | Effect | LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| −1 SD | −0.018 | −0.033 | −0.008 | ||||

| Mean | −0.028 | −0.043 | −0.015 | ||||

| +1 SD | −0.038 | −0.058 | −0.019 | ||||

| Consequent | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy | Work Engagement | ||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | |

| Job insecurity (JI) | −0.099 | 0.021 | <0.001 | −0.040 | 0.016 | <0.010 | |

| Self-efficacy (SE) | - | - | - | 0.47 | 0.025 | <0.001 | |

| Supervisor support (SS) | - | - | - | 0.317 | 0.023 | <0.001 | |

| SE × SS | - | - | - | 0.005 | 0.027 | ns | |

| R2 = 0.023 | R2 = 0.453 | ||||||

| F(1.872) = 20.610, p < 0.001 | F(4.869) = 180.115, p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Total, direct, and indirect effects of job insecurity on work engagement | |||||||

| Effect | SE | p | |||||

| Total effect | −0.136 | 0.022 | <0.001 | ||||

| Direct effect | −0.085 | 0.017 | <0.001 | ||||

| Indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| Indirect effect (through self-efficacy) | −0.050 (0.077) | 0.018 | −0.113 | −0.041 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pires, M.L. The Effects of Job Insecurity on Psychological Well-Being and Work Engagement: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070979

Pires ML. The Effects of Job Insecurity on Psychological Well-Being and Work Engagement: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):979. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070979

Chicago/Turabian StylePires, Maria Leonor. 2025. "The Effects of Job Insecurity on Psychological Well-Being and Work Engagement: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070979

APA StylePires, M. L. (2025). The Effects of Job Insecurity on Psychological Well-Being and Work Engagement: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070979