Adaptive Journeys: Accelerating Cross-Cultural Adaptation Through Study Tours

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Study Tours in the Context of Cross-Cultural Experience

2.2. Cross-Cultural Adaptation: From Classic Models to New Perspectives

2.3. Situated Learning and Embodied Cognition Theories in Study Tours

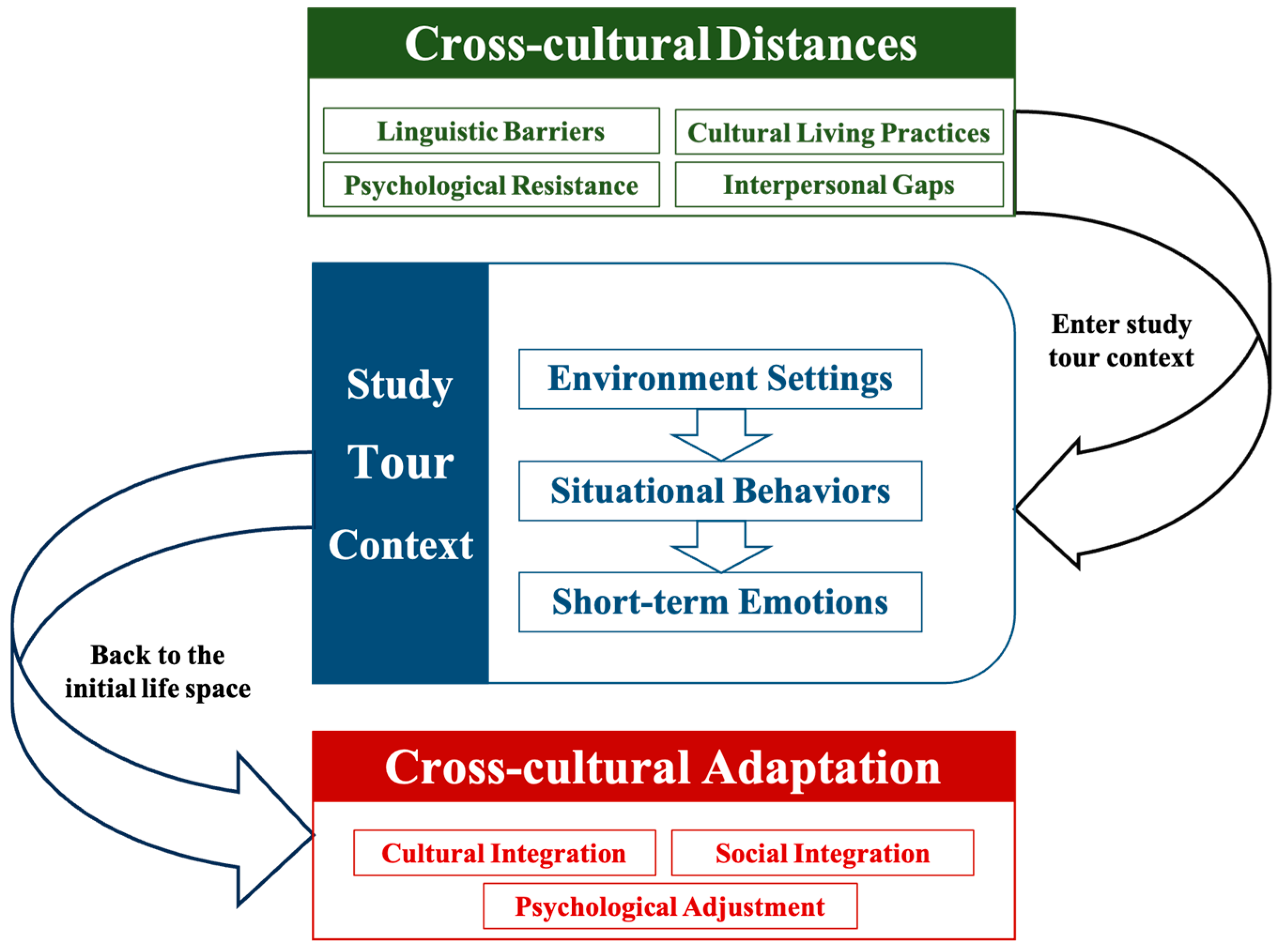

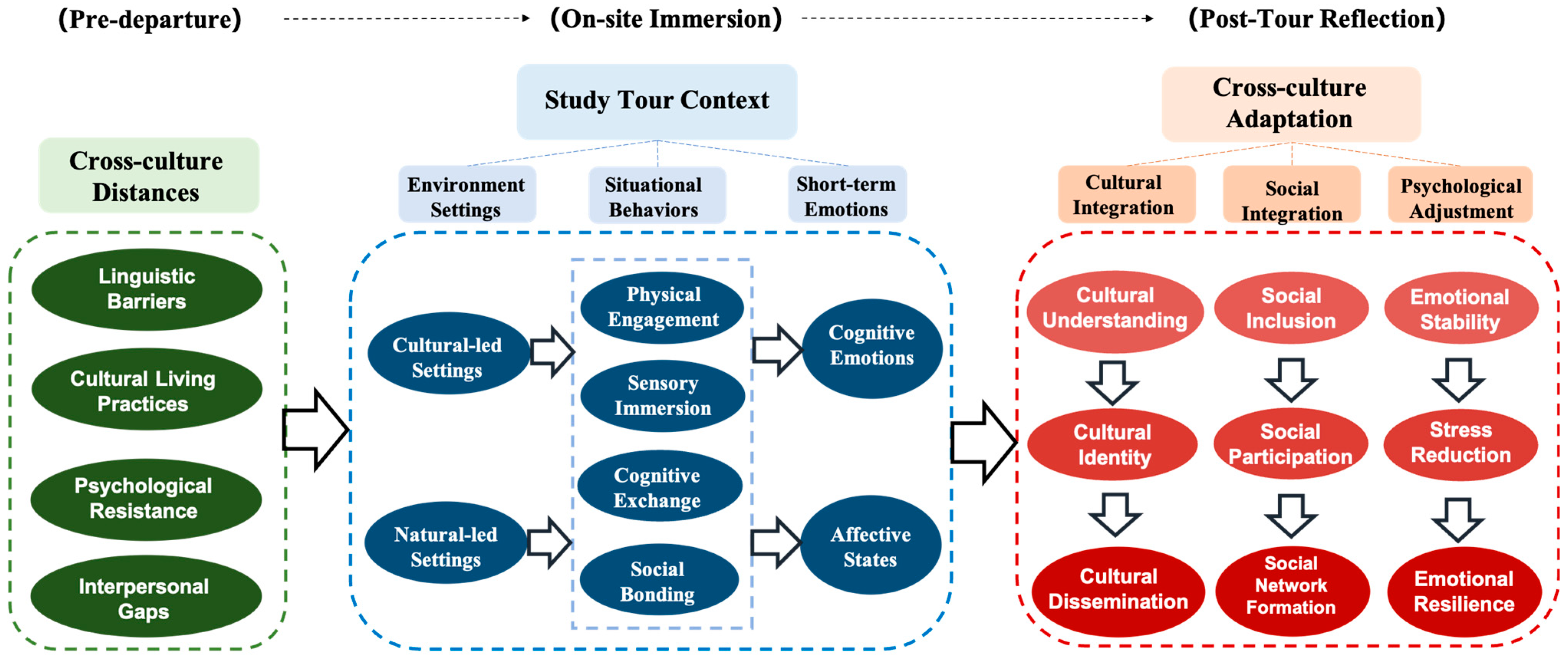

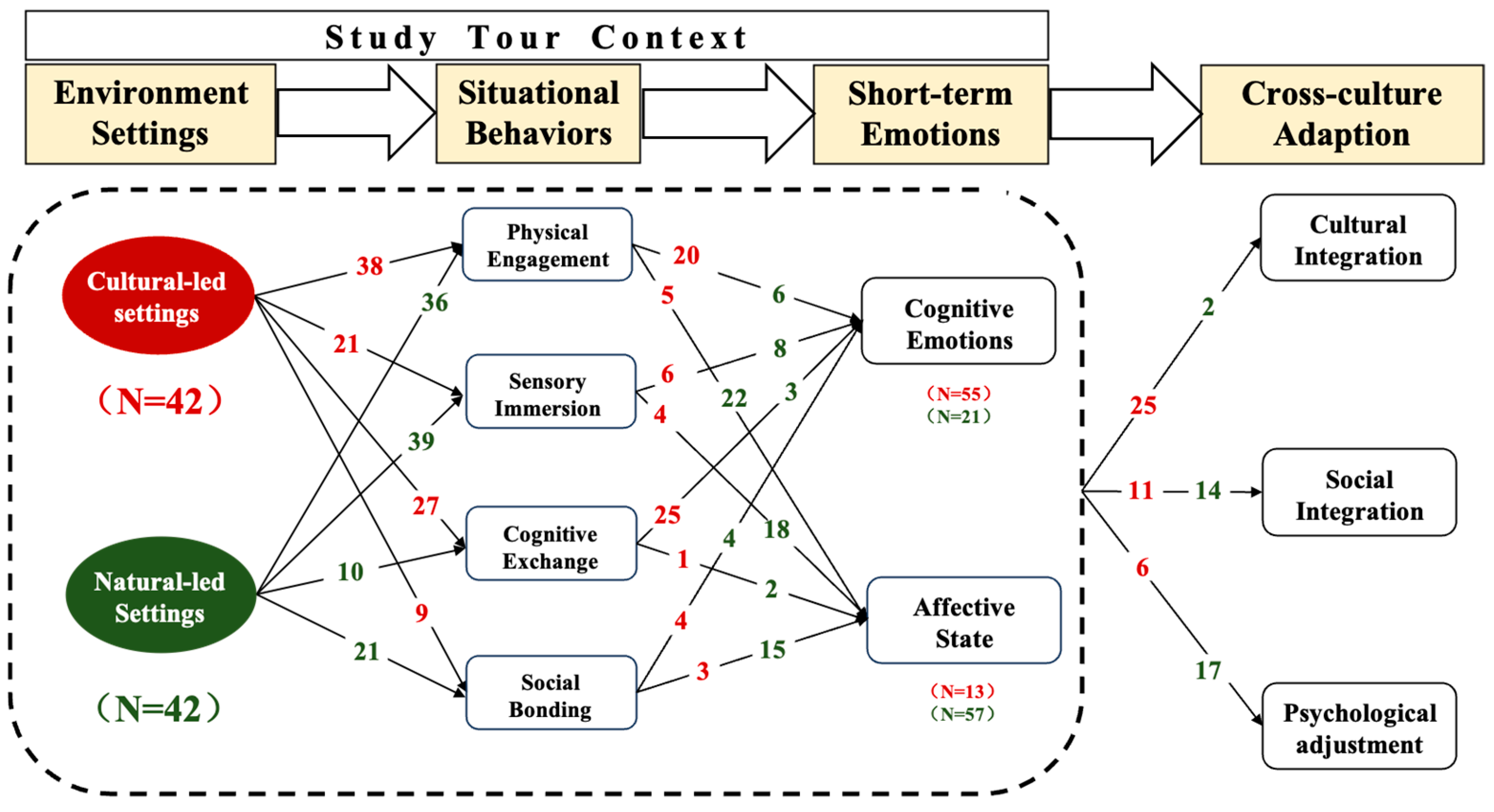

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method Selections

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Pre-Departure: Identifying Cross-Cultural Distance

“I was not able to communicate well with others usually because I could not speak English or Chinese very well, and I often felt disappointed.”(D33)

“In the morning, we had breakfast in the cafeteria. Although some of us were not used to it, I’m sure we’ll all love Chinese breakfast later.”(D67)

“I heard that Chinese people usually use tea to entertain guests”(D39)

“I was able to talk to my friends from the Dutch and German teams. I thought it would be difficult to interact with people from other countries, but everyone was very nice!”(V6)

4.2. On-Site Immersion: The Study Tour as a Catalyst for Adaptation

4.2.1. Environment Settings

“After arriving in Huangshan, the first trip was to Huizhou’s famous ink manufacturing place, where we watched how traditional ink is made and even tried grinding the ink ourselves. I was amazed at the precision and patience required—it gave me a new appreciation for Chinese calligraphy… The next day, climbing the Yellow Mountain and breathing the fresh air, I suddenly felt calm and deeply connected to nature. It was unforgettable.”(D16)

4.2.2. Situational Behaviors

“I even colored the top of the ink myself.”(D19)

“After listening to the tour guide, I realized the jade is valuable!”(D18)

“The scenery from there was stunning, and you could finally see China’s great mountains and rivers. The air there was so fresh, with the fragrance of leaves and birdsong all along the road, exactly like Europe!”(D66)

“Under the teacher’s language guidance and action correction, I learned the basic skills—seven steps and three stops.”(D8)

“Everyone is pleased today. It is also kind of nice to speak with the Netherlands and Germany team buddies; I thought the other countries were challenging to be my friends, but everyone is very nice! It is memorable to climb together with the class, I hope that the next few days everyone can be as happy as today”(D68)

“The uncles, aunts, and children there were very enthusiastic. Each of us learned to make cakes seriously. Although I didn’t get to experience it, an adorable kid gave me the cake she made!”(D49)

4.2.3. Short-Term Emotions

“The moment my self-created paper weaving painting was framed, my heart was filled with a sense of fulfillment”(D9)

“With the company of my companions, the journey was not tiring at all and was even very pleasant and joyful.”(D61)

4.3. Post-Tour Reflection: Bridging Experiences to Cross-Cultural Adaptation

4.3.1. Cultural Integration

“I found that people in Wuyishan love tea.”(D63)

“I love these cultures so much that whenever I visit a place that utilizes handmade items, I feel nothing but admiration and a secret hope that they will pass on these crafts, and I don’t want my future generations to see and feel nothing but cold, machine-made products.”(D17)

“I am very interested in the Chinese tea art. I visited the site, learned about the tea-making process from the lecturer, and recorded a video explanation in Filipino in the workshop. I plan to share the results of my study tour with Filipino primary and secondary school students in class when I return to my home country.”(D35)

4.3.2. Social Integration

“Thanks to Ms. Liu and Ms. Chen for their care and help during these three days, and I feel very close to them!”(D53)

“I plan to participate in the study activities organized by the college in the future because I can learn much knowledge from these activities that is not in the textbooks.”(D53)

“I also made a friend named Zhang Jing at that time. We still hang out together now.”(V4)

4.3.3. Psychological Adjustment

“I started not to be afraid to socialize with local students… Now, I feel happy with my life of studying abroad!”.(V2)

“Even if I still cannot understand clearly sometimes, I will ask the teacher after class… every teacher treats us with great patience.”(V1)

“Participating in the study tour is like a door, opening the way for me to become confident and comfortable… I even believe I will do better in any country I go to in the future.”(V1)

4.4. How Different Environmental Settings Shape Cross-Cultural Adaptation

“When I successfully made a bracelet, I really felt proud”(D22)

“After learning how to make the paper-cutting patterns, I strongly connected to the stories behind them. It wasn’t just fun—it made me proud to be part of this. I’ve already prepared a video to introduce it in my school back home.”(D21)

“Chatting with newly made friends by the seaside… I felt an unprecedented sense of relaxation and happiness.”(D31)

“Walking together by the lake and laughing with my classmates made me feel relaxed and connected—it was the first time I didn’t feel like a stranger here.”(D55)

5. Discussion

5.1. Cross-Cultural Distance as Pre-Embodied Constraints on Adaptation

5.2. Study Tours as Situated, Embodied Process Variables in Cross-Cultural Adaptation

5.3. Differentiated Impacts of Cultural- and Nature-Led Settings on Cross-Cultural Adaptation

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide: Exploring Cross-Cultural Adaptation Through Study Tours

- Can you briefly introduce yourself? (Nationality, academic program, length of stay in China.)

- When did you join the most recent study tour?

- Please describe the destination of your study tour and the main attractions you visited.

- What do you remember most vividly from the study tour? Why?

- Were there any cultural attractions (museums, factories, etc.) in the tour?

- ■

- How did you feel during or after these activities?

- Can you describe any activities that involved hands-on participation (e.g., craft making, physical tasks)?

- ■

- How did you feel during or after these activities?

- Were there any natural attractions (mountains, lakes, seaside, etc.) in the tour?

- ■

- How did you feel during or after these activities?

- Did you have any meaningful conversations or exchanges during the tour?

- With whom? What did you learn or feel?

- Were there any moments when you felt curious, proud, surprised, or emotionally touched?

- What triggered these emotions?

- Did you feel more relaxed, joyful, or connected to others during certain parts of the tour?

- Can you describe the scenes where this occurred?

- After the tour, did anything change in how you see or understand Chinese culture?

- Did the experience influence your social relationships with peers or local people?

- Do you think the study tour helped you become more emotionally comfortable or confident living in China?

- If you compare your experience before and after the tour, do you feel any changes in your mindset, behavior, or cultural openness?

- In your opinion, what aspects of the tour had the most lasting influence?

- Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience with the study tour and its impact on your life in China?

References

- Alsubaie, M. A. (2015). Examples of current issues in the multicultural classroom. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(10), 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2), 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (1997). Constructing and expanding a framework: Opportunities for developing acculturation research. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. (2020). Nature tourism and mental health: Parks, happiness, and causation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C., & Meng, Q. (2022). A systematic review of predictors of international students’ cross-cultural adjustment in China: Current knowledge and agenda for future research. Asia Pacific Education Review, 23(1), 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyasat, C. (2020). Overseas students in Thailand: A qualitative study of cross-cultural adjustment of French exchange students in a Thai university context. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 30(8), 1060–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W. M., & Klayklueng, S. (2018). Critical cultural awareness and identity development: Insights from a short-term Thai Language immersion. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 15(Suppl. 1), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (1995). The body, identity, and self: Adapting to impairment. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(4), 657–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K., & Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, B. Y., Takemura, K., Ou, C., Gale, A., & Heine, S. J. (2021). Considering cross-cultural differences in sleep duration between Japanese and Canadian university students. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0250671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chwialkowska, A. (2020). Maximizing cross-cultural learning from exchange study abroad programs: Transformative learning theory. Journal of Studies in International Education, 24(5), 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsett, P., Larmar, S., & Clark, J. (2019). Transformative intercultural learning: A short-term international study tour. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(3), 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglia, L., & Wilson, R. A. (2013). Embodied cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(3), 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhard, J. G. (2012). International students’ adjustment problems and behaviors. Journal of International Students, 2(2), 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Glenberg, A. M. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1(4), 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y., Gao, X., Li, M., & Lai, C. (2021). Cultural adaptation challenges and strategies during study abroad: New Zealand students in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 34(4), 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes-MacLellan, D. (2005). Three years in three days: School excursions as microcosm of Japanese junior high schools. Why Japan Matters, 2, 636–644. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., & Chen, G. (2023). A study on the construction of heritage identity in the study trip of heritage sites from the embodied perspective. World Regional Studies, 32(8), 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskhakova, M., & Bradly, A. (2022). Short-term study abroad research: A systematic review 2000–2019. Journal of Management Education, 46(2), 383–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, Sihombing, S. O., Antonio, F., Sijabat, R., & Bernarto, I. (2024). The role of tourist experience in shaping memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 19(4), 1319–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S. (2021). Acculturation in a globalised world: Implications for theory and educational policy and practice. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 23(1), 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger-Trayner, É. (2011). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (24. print). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1991). [Google Scholar]

- Leung, A. K. Y., Qiu, L., Ong, L., & Tam, K. P. (2011). Embodied cultural cognition: Situating the study of embodied cognition in socio-cultural contexts. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(9), 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Bai, M., Deng, H., Wu, Y., & Cui, R. (2024). Exploring children’s experiences on school field trips from children’s perspectives. Tourism Management Perspectives, 51, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Cui, Q., Xu, H., & Guia, J. (2022). Health and local food consumption in cross-cultural tourism mobility: An assemblage approach. Tourism Geographies, 24(6–7), 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, H., & Forsberg, C. (2023). Constructivist grounded theory and educational research: Constructing theories about teachers’ work when analysing relationships between codes. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 46(2), 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D., & Woodside, A. G. (2008). Grounded theory of international tourism behavior. Tourism Marketing, 24(4), 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X., & Gnoth, J. (2017). Elaborating on grounded theory in tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 65, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGladdery, C. A., & Lubbe, B. A. (2017a). International educational tourism: Does it foster global learning? A survey of South African high school learners. Tourism Management, 62, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGladdery, C. A., & Lubbe, B. A. (2017b). Rethinking educational tourism: Proposing a new model and future directions. Tourism Review, 72(3), 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W., & Luetz, J. M. (2021). The impact of short-term cross-cultural experience on the intercultural competence of participating students: A case study of australian high school students. Social Sciences, 10(8), 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, K. (1960). Cultural Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments. Practical Anthropology, os-7(4), 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B. C., & Battista, A. (2020). Situated learning theory in health professions education research: A scoping review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(2), 483–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, F. L., Matt, J. J., McCaw, W. P., Kero, P., Stewart, C., & Haddouch, R. (2014). International study tour groups. Journal of Education and Learning, 3(1), p52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, L., & Zahavi, D. (2023). Sociality and embodiment: Online communication during and after COVID-19. Foundations of Science, 28(4), 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, T., Broomhall, S., McEwan, J., & Majocha, E. (2010). Adult learning in study tour. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 50(2), 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Porth, S. J. (1997). Management education goes international: A model for designing and teaching a study tour course. Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A. B., Riaz, H., Ahmad, A., Ashraf, M. S., & Iqbal, T. (2023). Cultural adaption of asian students in China. Biological Times, 2(10), 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Riggan, J., Gwak, S. S., Lesnick, J., Jackson, K., & Olitsky, S. (2011). Meta-travel: A critical inquiry into a China study tour. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 21(1), 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, K., van Miert, D., & Enenkel, K. A. E. (Eds.). (2022). Memory and identity in the learned world: Community formation in the early modern world of learning and science. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, O. (2013). WHAT SHOULD NATURE SOUND LIKE?: Techniques of engagement with nature sites and sonic preferences of Israeli visitors. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, W., & Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14(4), 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozen, A. I. (2020). Cross-cultural social skills of Turkish students in Japan: Implications for overcoming academic and social difficulties during cross-cultural transition. IAFOR Journal of Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences, 6(1), 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (2003). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publ. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). (2023). International students. Migration Data Portal. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/international-students (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Vieira, N. G. S., Pocinho, M., Nunes, C. P., & Sousa, S. S. (2022). Engaging in educational tourism: An academic response. Journal of Tourism, Sustainability and Well-Being, 10(2), 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viwatronnakit, H., Inthachak, M., Trakarnsiriwanit, K., & Nanta, S. (2019). Cross culture communication effecting to volunteer tourism tourist activities in Chiangmai, Thailand. PSAKU International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 8(2), 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. P., & Beard, C. (2013). Experiential learning: A handbook for education, training and coaching. Kogan Page Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Young, T. J., & Schartner, A. (2014). The effects of cross-cultural communication education on international students’ adjustment and adaptation. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(6), 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Zhou, Y., & Stodolska, M. (2022). Socio-cultural adaptation through leisure among Chinese international students: An experiential learning approach. Leisure Sciences, 44(2), 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y., Xu, S., Lin, Q., & Zhang, M. (2022). The process of perception of tourism destination vitality and its influencing factors—An exploratory study based on rootedness theory. Human Geography, 37(02), 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant ID | Nationality | Ethnic Background | Length of Stay in China | Language Ability | Purpose for Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | Thailand | Thai | 3 years | High | Undergraduate in Business |

| V2 | Malaysia | Malaysian Chinese | 2 years | Intermediate (HSK 4) | Bachelor’s in Chinese Culture |

| V3 | Indonesia | Javanese | 8 months | Basic | Short-term Exchange |

| V4 | Laos | Lao | 1 year | Basic | Bachelor’s in Fine Arts |

| V5 | Thailand | Thai | 1 year | Intermediate | Chinese Language Training |

| V6 | Malaysia | Malaysian Chinese | 6 months | Basic | Pre-University Language Preparation |

| Data Snippet | Codes | Initial Concepts | Labels | Memos | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “It was my first time to study abroad … I couldn’t communicate well with others …I didn’t speak English or Chinese well.” | First time abroad; could not communicate; poor Chinese and English | difficulty in expression, lack of communication skills; feeling of strangeness | Early-stage language barrier | The overlap of language barriers and first-time study abroad may imply emotional tension or unease, even though no explicit emotions are expressed. This warrants further exploration in the emotional dimension. | Diaries |

| “We went to Gulangyu Island… visited the Pie Museum…local people taught us learned how to make pie…I made a video and want to sharethe process with my good friends.” | Cultural visit; food-making; interaction with local people; sharing cultural experiences | hands-on learning from locals; desire to share the host culture | Cultural participation; cultural storytelling | Cultural participation and social interaction often co-occur; it is worth examining whether this constitutes a recurring interaction pattern. Students show more signs of cultural communication when participating in cultural activities. | |

| “We went to Wuyi Mountain… climbed a mountain… bamboo rafting… the scenery was beautiful… relaxing… made a friend…we are still good friends now.” | Mountain climbing; bamboo rafting; scenic appreciation; relaxation; making friends | natural site visit; physical participation; emotional relief building lasting intercultural friendships | Natural immersion; physical engagement; social bonding | Frequent mentions of nature and relaxation appear to be closely linked to bodily sensations. | Interview |

| Main Categories | Sub-Categories | |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-cultural Distance | Linguistic Barriers | |

| Cultural Living Practices | ||

| Psychological Resistance | ||

| Interpersonal gaps | ||

| Study Tour Context | Environment Settings | Culture-led Settings |

| Nature-led Settings | ||

| Situational Behaviors | Physical Engagement | |

| Sensory immersion | ||

| Cognitive Exchange | ||

| Social Bonding | ||

| Short-term Emotions | Cognitive Emotions | |

| Affective State | ||

| Cross-culture Adaptation | Cultural Integration | Cultural Understanding |

| Cultural Identity | ||

| Cultural Dissemination | ||

| Social Integration | Social Inclusion | |

| Social Participation | ||

| Social Network Formation | ||

| Psychological Adjustment | Emotional Stability | |

| Stress Reduction | ||

| Emotional Resilience | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Z.; Huang, A.; Yin, Z. Adaptive Journeys: Accelerating Cross-Cultural Adaptation Through Study Tours. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070973

Huang Z, Huang A, Yin Z. Adaptive Journeys: Accelerating Cross-Cultural Adaptation Through Study Tours. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070973

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Ziye, Anmin Huang, and Ziyan Yin. 2025. "Adaptive Journeys: Accelerating Cross-Cultural Adaptation Through Study Tours" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070973

APA StyleHuang, Z., Huang, A., & Yin, Z. (2025). Adaptive Journeys: Accelerating Cross-Cultural Adaptation Through Study Tours. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070973