Revisiting Public Trust and Media Influence During COVID-19 Post-Vaccination Era—Waning of Anxiety and Depression Levels Among Skilled Workers and Students in Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

- Healthcare workers (physicians, nurses/medical technicians);

- Education workers (teachers, university staff);

- Military personnel;

- College students enrolled in undergraduate or graduate programs.

2.4. Variables

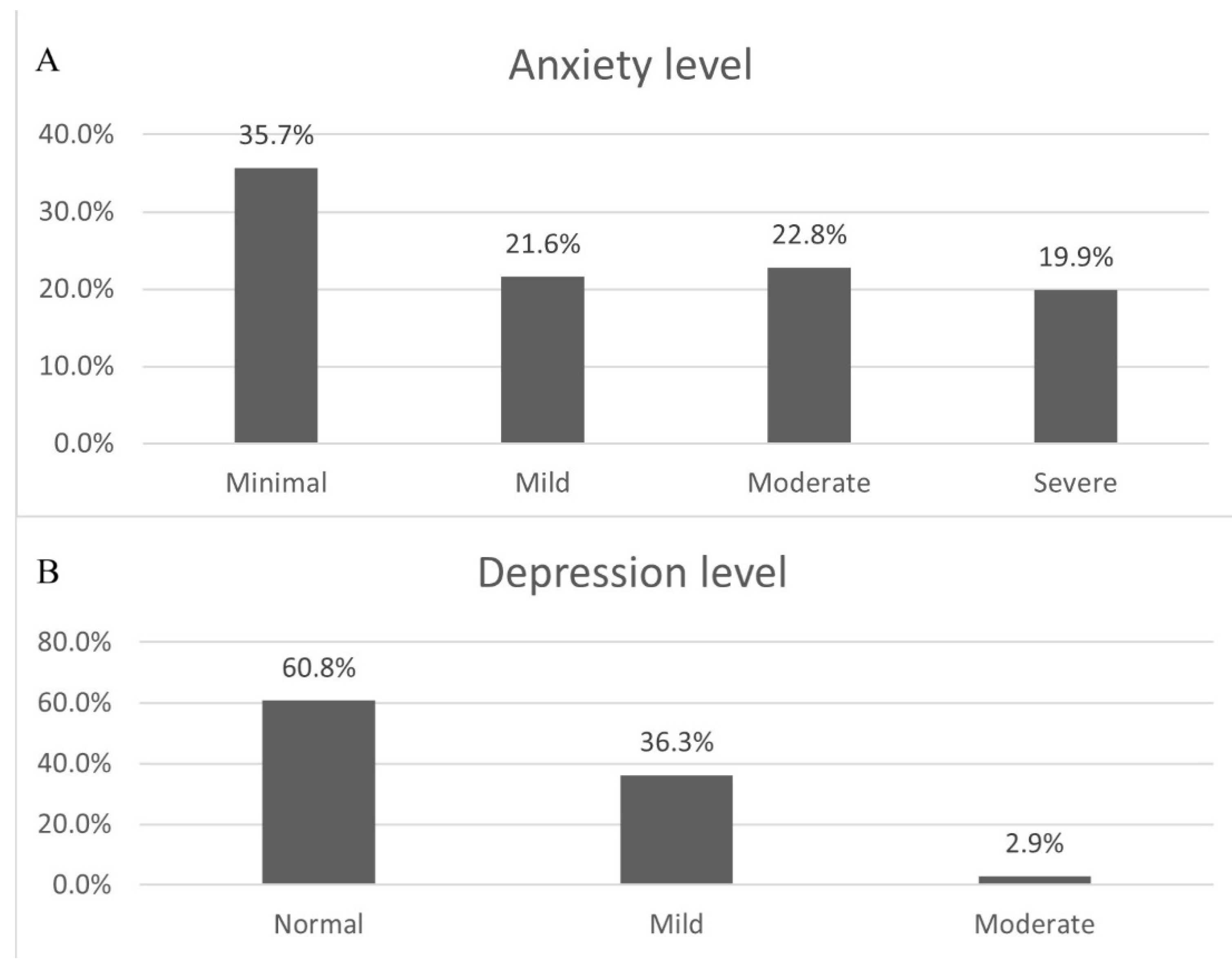

- Level of anxiety—Measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), a 21-item scale with scores categorized as low (0–21), moderate (22–35), or severe (≥36) anxiety (Beck et al., 1988);

- Level of depression—Assessed via the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), a 20-item tool classifying scores as normal (20–49), mild (50–59), moderate (60–69), or severe (≥70) depression (Zung, 1965).

- Disturbance by COVID-19-related information—Four dichotomous (yes/no) items evaluated distress from media reports, independent information-seeking, lack of information, and perceived transmission risk;

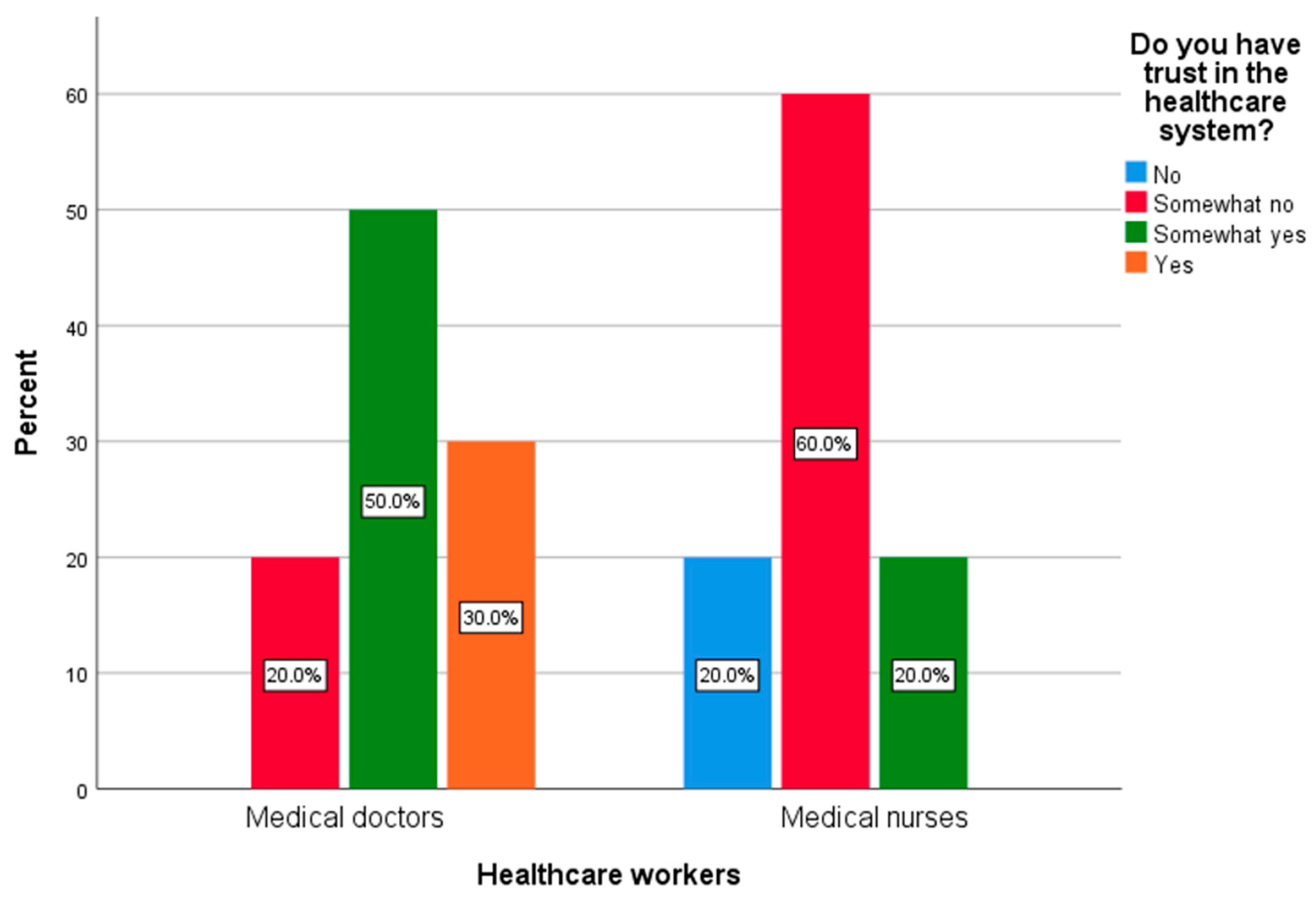

- Trust in institutions—Two dichotomous items assessed confidence in Serbia’s healthcare system and government-proposed preventive measures.

2.5. Data Sources/Measurements

2.6. Bias

- Selection Bias: Snowball sampling may have overrepresented individuals within the authors’ networks or those with stronger opinions about COVID-19.

- Non-Response Bias: The 30-day recruitment window and lack of incentives likely excluded busy or disinterested individuals.

- Self-Report Bias: Social desirability may have led to underreporting of mental health symptoms or distrust in institutions.

2.7. Study Size

2.8. Quantitative Variables

2.9. Statistical Methods

2.10. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Between-Group Comparisons

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Global Context

- Approximately one-quarter reported decreased disturbance levels from these factors;

- Half to two-thirds reported no change;

- Around 10% reported increased disturbance (over 15% specifically cited increased disturbance from media reports).

4.2. Public Trust in General and Institutional Dynamics

4.3. Media Influence and Mental Health

4.4. COVID-19-Related Public Trust

4.5. Population of Students

4.6. Healthcare Workers

4.7. Contribution of the Study to the Existing Theoretical Frameworks

4.8. Implications for Policy and Practice

- Institutional Reforms: Rebuilding trust requires transparent communication and anti-corruption measures. For example, Serbia’s Crisis Team, criticized for opaque decision-making (Mandić, 2020), could adopt participatory frameworks involving healthcare workers and educators in policy design—a strategy that improved compliance in Germany and New Zealand (OECD, 2021).

- Mental Health Support: Targeted programs for high-risk groups are essential. Universities could integrate mental health screenings into academic services, while hospitals might offer resilience training for nurses. Japan’s “vaccine ambassador” model, which leveraged trusted community figures to boost uptake, offers a blueprint for Serbia (Yoda & Katsuyama, 2021).

- Media Regulation: Combating misinformation requires collaboration between governments and tech platforms. Serbia could emulate the EU’s Digital Services Act, which mandates transparency in algorithmic content prioritization, to curb viral conspiracy theories (Cervi et al., 2023).

- Occupational Equity: Addressing nurse–physician trust disparities demands systemic changes, such as equitable resource allocation and leadership opportunities for nurses. Costa Rica’s nurse-led vaccination campaigns, which improved public confidence, highlight the value of empowering marginalized healthcare roles (Larson et al., 2018).

4.9. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease-19 |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| SDS | Self-Rating Depression Scale |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

References

- Al-Amer, R., Maneze, D., Everett, B., Montayre, J., Villarosa, A. R., Dwekat, E., & Salamonson, Y. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination intention in the first year of the pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(1–2), 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A., Kerzic, D., Ravselj, D., Tomazevic, N., & Umek, L. (2021). Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on life of higher education students: Global survey dataset from the first wave. Data in Brief, 39, 107659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballmann, J., Helmer, S. M., Berg-Beckhoff, G., Dalgaard Guldager, J., Jervelund, S. S., Busse, H., Pischke, C. R., Negash, S., Wendt, C., & Stock, C. (2022). Is lower trust in COVID-19 regulations associated with academic frustration? A comparison between Danish and German university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, N., Mustapha, T., Khubchandani, J., & Price, J. H. (2021). The nature and extent of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in healthcare workers. Journal of Community Health, 46(6), 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelos, M., & Hercigonja, S. (2022, April). (Mis)trust and (in)security during the second year of the pandemics: Attitudes of Serbian citizens towards the COVID-19 pandemic. Belgrade Centre for Security Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Boda, Z., & Medve-Balint, G. (2020). Politicized institutional trust in East Central Europe. Taiwan Journal of Democracy, 16(1), 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Budzyńska, N., & Moryś, J. (2023). Anxiety and depression levels and coping strategies among polish healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F., Pantovic, A., Al-Ajlouni, Y., Failla, G., & Ricciardi, W. (2021). Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Free Elections and Democracy. (2017, June). Political activism of citizens of Serbia. Center for Free Elections and Democracy. [Google Scholar]

- Cervi, L., García, F., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2021). Populism, Twitter, and COVID-19: Narrative, fantasies, and desires. Social Sciences, 10(8), 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L., Tejedor Calvo, S., & Robledo-Dioses, K. (2023). Comunicación digital y ciudad: Análisis de las páginas web de las ciudades más visitadas en el mundo en la era de la COVID-19. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 81, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Qi, H., Liu, R., Feng, Y., Li, W., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., Jackson, T., Wang, G., & Xiang, Y. T. (2021). Depression, anxiety and associated factors among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COCONEL Group. (2020). A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, P. K., Douglas, D. B., Harrigan, D. C., & Douglas, K. M. (2009). Preparing for pandemic influenza and its aftermath: Mental health issues considered. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 11(3), 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Džunić, M., Golubovic, N., & Marinkovic, S. (2020). Determinants of institutional trust in transition economies: Lessons from Serbia. Economic Annals, 65(225), 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K. A., Bloomstone, S. J., Walder, J., Crawford, S., Fouayzi, H., & Mazor, K. M. (2020). Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: A survey of U.S. adults. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(12), 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedom House. (2022). Freedom in the world 2022: Serbia. Freedom House. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/country/serbia/freedom-world/2022 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Gallup Europe. (2010). Gallup Balkan Monitor—Insights and perceptions: Voices of the Balkan: 2010 summary of findings. Gallup Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, L. P., & Duarte, E. (2020). Nonpharmaceutical interventions for tackling the COVID-19 epidemic in Brazil. Epidemiologia e Servicos de Saude: Revista do Sistema Unico de Saude do Brasil, 29(2), e2020222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golubovic, N., Dzunic, M., & Marinkovic, S. (2017). The origins of institutional trust in Serbia from the perspective of performance-based approach. In E. Dogan, & S. A. Koc (Eds.), Institutions, national identity, power, and governance in the 21st century (pp. 209–232). IJOPEC Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gozgor, G. (2022). Global evidence on the determinants of public trust in governments during the COVID-19. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(2), 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercigonja, S. (2020, December 11). Srbija u raljama pandemije COVID-19. Belgrade Centre for Security Policy. Available online: https://bezbednost.org/publikacija/srbija-u-raljama-pandemije-covid-19/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Jamison, A. M., Quinn, S. C., & Freimuth, V. S. (2019). “You don’t trust a government vaccine”: Narratives of institutional trust and influenza vaccination among African American and white adults. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 221, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janic, O. (2022). Institutional trust as a moderator in the relationship between trust in science and youths’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination [Master’s thesis, University of Novi Sad Faculty of Philosophy]. Available online: https://remaster.ff.uns.ac.rs/materijal/punirad/Master_rad_20220908_psi_320017_2021.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11(1), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehi, T., Khan, R., Dos Santos, H., & Majzoub, N. (2023). Effect of COVID-19 outbreak on anxiety among students of higher education; A review of literature. Current Psychology, 42, 17475–17489, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L. C., Soveri, A., Lewandowsky, S., Karlsson, L., Karlsson, H., Nolvi, S., Karukivi, M., Lindfelt, M., & Antfolk, J. (2021). Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences, 172, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T. (2020). The changes in the effects of social media use of Cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technology in Society, 63, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, A. M. (2020). Break the silence: Physician suicide in the time of COVID-19. Missouri Medicine, 117(5), 426–429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V. M., Pandi-Perumal, S. R., Trakht, I., & Thyagarajan, S. P. (2021). Strategy for COVID-19 vaccination in India: The country with the second highest population and number of cases. NPJ Vaccines, 6(1), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L. J., & De Los Santos, J. A. A. (2020). COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H. J., Clarke, R. M., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Levine, Z., Schulz, W. S., & Paterson, P. (2018). Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(7), 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A., Lewandowski, T., Rudzki, G., Próchnicki, M., Stryjkowska-Góra, A., Laskowska, B., Wilk, P., Skóra, B., & Rudzki, S. (2024). Anxiety levels among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccines, 12(4), 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C., Tong, Y., Bai, Y., Zhao, Z., Quan, W., Liu, Z., Wang, J., Song, Y., Tian, J., & Dong, W. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among Chinese international students in US colleges during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 17(4), e0267081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubicic, M. (2022, January 9). Dezinformacije i korona: U 2021. Dominirali antivakseri. Raskrinkavanje. Available online: https://www.raskrikavanje.rs/page.php?id=Dezinformacije-i-korona-U-2021--dominirali-antivakseri-945 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Mandić, S. (2020, July 30). Krizni štab, revealed. Pescanik. Available online: https://pescanik.net/krizni-stab-revealed/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Markovic, I., Nikolovski, S., Milojevic, S., Zivkovic, D., Knezevic, S., Mitrovic, A., Fiser, Z., & Djurdjevic, D. (2020). Public trust and media influence on anxiety and depression levels among skilled workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in Serbia. Vojnosanitetski Pregled, 77(11), 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Anderson, K. E., Han, H., & Barry, C. L. (2020). Psychological distress and COVID-19-related stressors reported in a longitudinal cohort of US adults in April and July 2020. JAMA, 324(24), 2555–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milutinović, I. (2022). Media pluralism in competitive authoritarian regimes—A comparative study: Serbia and Hungary. Sociologija, 64(2), 272–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F., Sadiq, A., Raziq, A., Iqbal, Q., Haider, S., Saleem, F., & Bashaar, M. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and stress among nurses during the COVID-19 Wave III: Results of a cross-sectional assessment. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 14, 3093–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehal, K. R., Steendam, L. M., Campos Ponce, M., van der Hoeven, M., & Smit, G. S. A. (2021). Worldwide vaccination willingness for COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines, 9(10), 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederdeppe, J., Robert, S. A., & Kindig, D. A. (2011). Qualitative research about attributions, narratives, and support for obesity policy, 2008. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(2), A39. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolovski, S. (2021a, December 24–25). Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant—Transmissibility, virulence, illness severity, prevention, and vaccine efficacy compared to previous and future variants. 3rd International Conference on Medical & Health Sciences, Online. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolovski, S. (2021b, December 24–25). Pandemic, ecology, and human rights—A Bermuda triangle of COVID-19. 3rd International Conference on Medical & Health Sciences, Online. [Google Scholar]

- Novilla, M. L. B., Moxley, V. B. A., Hanson, C. L., Redelfs, A. H., Glenn, J., Donoso Naranjo, P. G., Smith, J. M. S., Novilla, L. K. B., Stone, S., & Lafitaga, R. (2023). COVID-19 and psychosocial well-being: Did COVID-19 worsen U.S. frontline healthcare workers’ burnout, anxiety, and depression? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Enhancing public trust in COVID-19 vaccination: The role of governments. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2021/05/enhancing-public-trust-in-covid-19-vaccination-the-role-of-governments_36749555.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Oksanen, A., Kaakinen, M., Latikka, R., Savolainen, I., Savela, N., & Koivula, A. (2020). Regulation and trust: 3-month follow-up study on COVID-19 mortality in 25 European countries. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e19218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2021). Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. The Lancet Regional Health. Europe, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretti-Watel, P., Larson, H. J., Ward, J. K., Schulz, W. S., & Verger, P. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Clarifying a theoretical framework for an ambiguous notion. PLoS Currents, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesic, J., Biresev, A., & Petrovic Trifunovic, T. (2021). Political disaffection and disengagement in Serbia. Sociologija, 63(2), 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjesivac, I. (2016). The effects of culture and performance on trust in news media in post-communist Eastern Europe: The case of Serbia. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(4), 1191–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadic, D., Pavlovic, Z., & Mihailovic, S. (2020, March 4). Youth study Serbia 2018/2019. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Pouralizadeh, M., Bostani, Z., Maroufizadeh, S., Ghanbari, A., Khoshbakht, M., Alavi, S. A., & Ashrafi, S. (2020). Anxiety and depression and the related factors in nurses of Guilan University of Medical Sciences hospitals during COVID-19: A web-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 13, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, S. C., Jamison, A. M., & Freimuth, V. (2021). Communicating effectively about emergency use authorization and vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 111(3), 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoi, M., & Lupu, A. (2017). Understanding institutional trust. What does it mean to trust the health system? In A. Maturo, S. Hoskova-Mayerova, D. T. Soitu, & J. Kacprzyk (Eds.), Recent trends in social systems: Quantitative theories and quantitative models (pp. 11–22). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Reger, M. A., Stanley, I. H., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—A perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1093–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safiye, T., Gutić, M., Dubljanin, J., Stojanović, T. M., Dubljanin, D., Kovačević, A., Zlatanović, M., Demirović, D. H., Nenezić, N., & Milidrag, A. (2023). Mentalizing, resilience, and mental health status among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(8), 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K., Torous, J., Caine, E. D., & De Choudhury, M. (2020). Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Large-scale quasi-experimental study on social media. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11), e22600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhbardsiri, H., Doustmohammadi, M. M., Afshar, P. J., Heidarijamebozorgi, M., Khankeh, H., & Beyramijam, M. (2021). Anxiety, stress and depression levels among nurses of educational hospitals in Iran: Time of performing nursing care for suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavujevic, Z. (2011). The citizens of Serbia’s views of democracy. Serbian Political Thought, 4(2), 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srdic, M. (2021). Podrška preduzetnicima tokom pandemije COVID-19. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Stjepic, D. (2021, March 30). Analiza izvora lažnih vesti o pandemiji. Novosadska novinarska skola. Available online: https://novinarska-skola.org.rs/sr/analiza-izvora-laznih-vesti-o-pandemiji/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Stojanovic, B., & Ivkovic, A. (2022). Alternativni izveštaj o položaju i potrebama mladih u Republici Srbiji. Krovna organizacija mladih Srbije. [Google Scholar]

- Tamrakar, P., Pant, S. B., & Acharya, S. P. (2023). Anxiety and depression among nurses in COVID and non-COVID intensive care units. Nursing in Critical Care, 28(2), 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government of the Republic of Serbia. (2020a, March 13). COVID-19 crisis response team formed. The Government of the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/151314/covid-19-crisis-response-team-formed.php (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- The Government of the Republic of Serbia. (2020b, March 19). Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport closes for all commercial international flights. The Government of the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/151803/belgrade-nikola-tesla-airport-closes-for-all-commercial-international-flights.php (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Tokić, A., Gusar, I., & Nikolic Ivanisevic, M. (2023). Mental health and well-being in healthcare workers in Croatia during COVID19 pandemic: Longitudinal study on convenient sample. Medica Jadertina, 53(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. (2022). Corruption perceptions index 2021: Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Transparency International. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021%20 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Troiano, G., & Nardi, A. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health, 194, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. (2023, May 5). WHO chief declares end to COVID-19 as a global health emergency. United Nations. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136367?form=MG0AV3 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Usher, K., Durkin, J., & Bhullar, N. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(3), 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaine, L., Grēve, M., Zolovs, M., Ancāne, G., Utināns, A., & Briģis, Ģ. (2024). Self-esteem and occupational factors as predictors of the incidence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latvia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whetten, K., Leserman, J., Whetten, R., Ostermann, J., Thielman, N., Swartz, M., & Stangl, D. (2006). Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59(4), 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, H. M., Griffin, B. J., Shoji, K., Love, T. M., Langenecker, S. A., Benight, C. C., & Smith, A. J. (2021). Pandemic-related mental health risk among front line personnel. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 137, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K. K., Chan, S. K., & Ma, T. M. (2005). Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(1), 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, T., & Katsuyama, H. (2021). Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines, 9(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W. W. (1965). A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Have You Experienced Disturbance | Never n (%) | Very Rarely n (%) | Rarely n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Usually n (%) | Often n (%) | Very Often n (%) | Always n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| by the media reports regarding the outbreak? | 44 (25.7) | 39 (22.8) | 22 (12.9) | 32 (18.7) | 14 (8.2) | 7 (4.1) | 8 (4.7) | 5 (2.9) |

| by the information from other sources you have learned on your own initiative? | 49 (28.7) | 37 (21.6) | 26 (15.2) | 27 (15.8) | 14 (8.2) | 4 (2.3) | 11 (6.4) | 3 (1.8) |

| by the lack of the information regarding the COVID-19 outbreak and the disease itself? | 49 (28.7) | 36 (21.1) | 28 (16.4) | 29 (17) | 8 (4.7) | 11 (6.4) | 6 (3.5) | 4 (2.3) |

| by the possibility of virus transmission from other people despite personal preventive measures you applied? | 48 (28.1) | 28 (16.4) | 26 (15.2) | 35 (20.5) | 10 (5.8) | 9 (5.3) | 12 (7) | 3 (1.8) |

| Compared to the Period Prior to the Vaccination Implementation, What Was the Change in the Disturbance You Experienced | It Decreased n (%) | It Did Not Change n (%) | It Increased n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| by the media reports regarding the outbreak? | 48 (28.1) | 97 (56.7) | 26 (15.2) |

| by the information from other sources you learned on your own initiative? | 42 (24.6) | 108 (63.2) | 21 (12.3) |

| by the lack of the information regarding the COVID-19 outbreak and the disease itself? | 38 (22.2) | 115 (67.3) | 18 (10.5) |

| by the possibility of virus transmission from other people despite personal preventive measures you applied? | 45 (26.3) | 112 (65.5) | 14 (8.2) |

| Compared to the period prior to the vaccination implementation, how did your trust change | It decreased n (%) | It did not change n (%) | It increased n (%) |

| in the healthcare system | 25 (14.6) | 119 (69.6) | 27 (15.8) |

| in the preventive measures proposed by the Crisis team | 40 (23.4) | 120 (70.2) | 11 (6.4) |

| Answers n (%) | The Degree of the COVID-19 Outbreak Influence on the BAI Responses | The Degree of the COVID-19 Outbreak Influence on the SDS Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Smallest degree of influence | 34 (19.9) | 32 (18.7) |

| Very small degree of influence | 32 (18.7) | 39 (22.8) |

| Somewhat small degree of influence | 45 (26.3) | 46 (26.9) |

| Somewhat high degree of influence | 43 (25.1) | 36 (21.1) |

| Very high degree of influence | 9 (5.3) | 10 (5.8) |

| Highest degree of influence | 8 (4.7) | 8 (4.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamovic, M.; Nikolovski, S.; Milojevic, S.; Zdravkovic, N.; Markovic, I.; Djokic, O.; Tomic, S.; Burazor, I.; Zivkov Saponja, D.; Gacic, J.; et al. Revisiting Public Trust and Media Influence During COVID-19 Post-Vaccination Era—Waning of Anxiety and Depression Levels Among Skilled Workers and Students in Serbia. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 939. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070939

Adamovic M, Nikolovski S, Milojevic S, Zdravkovic N, Markovic I, Djokic O, Tomic S, Burazor I, Zivkov Saponja D, Gacic J, et al. Revisiting Public Trust and Media Influence During COVID-19 Post-Vaccination Era—Waning of Anxiety and Depression Levels Among Skilled Workers and Students in Serbia. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):939. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070939

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamovic, Miljan, Srdjan Nikolovski, Stefan Milojevic, Nebojsa Zdravkovic, Ivan Markovic, Olivera Djokic, Slobodan Tomic, Ivana Burazor, Dragoslava Zivkov Saponja, Jasna Gacic, and et al. 2025. "Revisiting Public Trust and Media Influence During COVID-19 Post-Vaccination Era—Waning of Anxiety and Depression Levels Among Skilled Workers and Students in Serbia" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 939. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070939

APA StyleAdamovic, M., Nikolovski, S., Milojevic, S., Zdravkovic, N., Markovic, I., Djokic, O., Tomic, S., Burazor, I., Zivkov Saponja, D., Gacic, J., Petkovic, J., Knezevic, S., Spiler, M., Svetozarevic, S., & Adamovic, A. (2025). Revisiting Public Trust and Media Influence During COVID-19 Post-Vaccination Era—Waning of Anxiety and Depression Levels Among Skilled Workers and Students in Serbia. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 939. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070939