Media Representations of Aging and Their Psychological Impact: Age Anxiety Among Older Korean Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Theoretical Framework

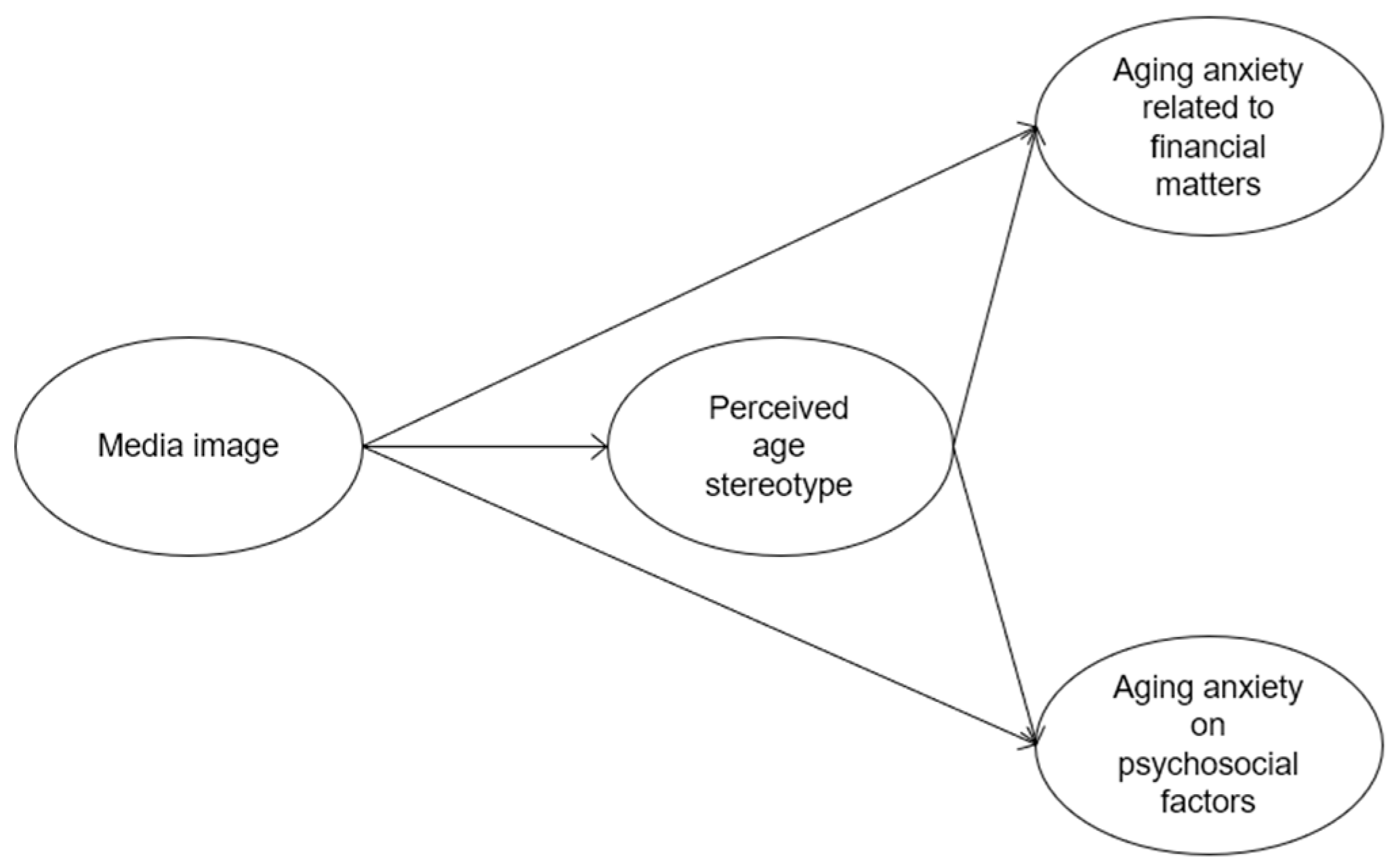

1.3. Study Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Aging Anxiety

2.2.2. Media Representation

2.2.3. Perceived Age Stereotypes

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Information

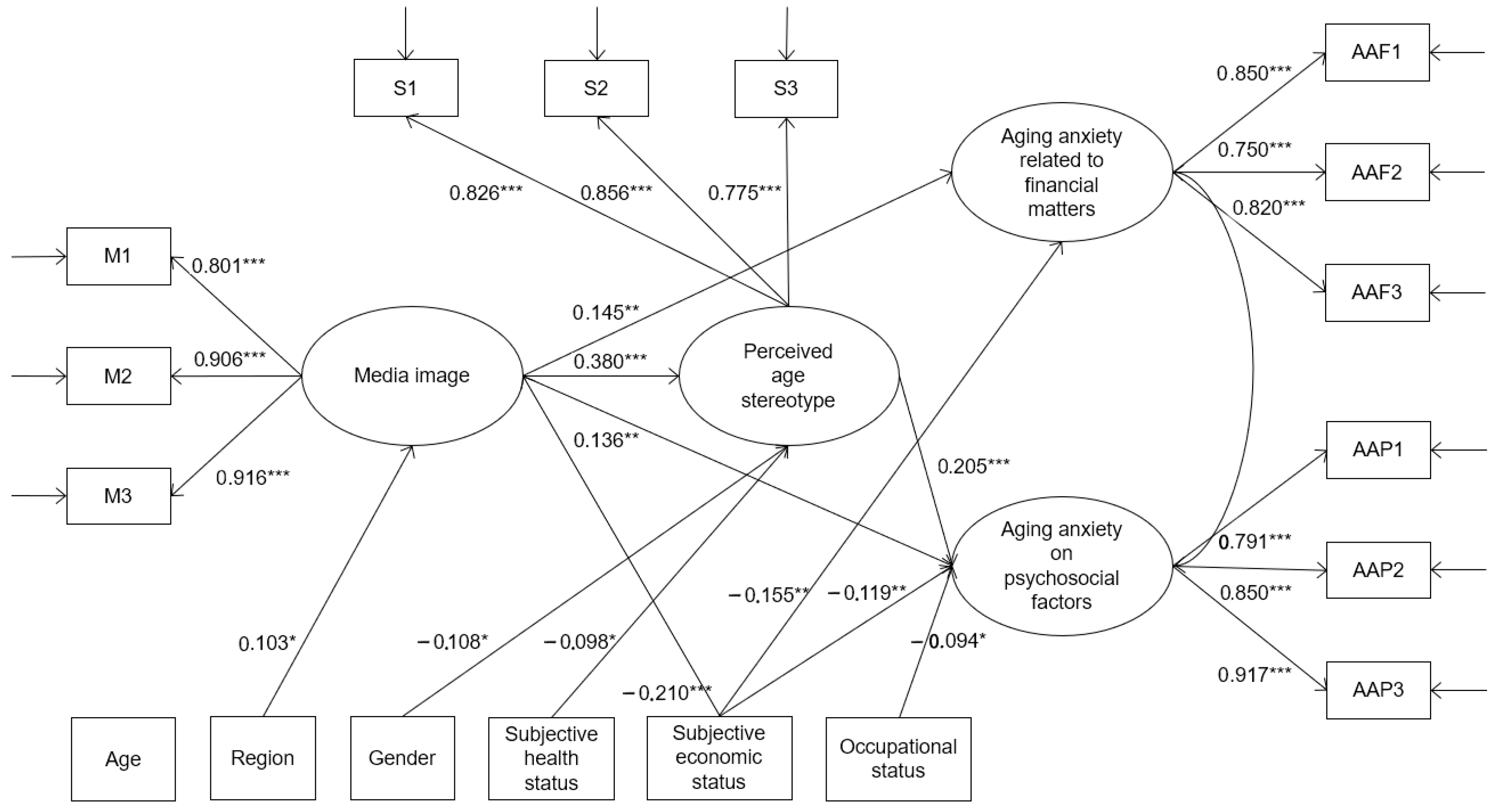

3.2. Measurement Model

3.3. Structural Model

3.4. Assessment of Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, M. S., Walter, E. E., & Swann, C. (2019). Sedentary behaviour and risk of anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S., Kang, H., & Chung, S. (2018). Validity and reliability of the perceived elderly stigma and the relationship between the stigma and demographic factors. Journal of the Korean Gerontological Society, 3(1), 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Y. S., & Bodner, E. (2022). Aging anxiety in older adults. GeroPsych, 35(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Y. S., & Segel-Karpas, D. (2021). Aging anxiety, loneliness, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged adults: The moderating role of ageism. Journal of Affective Disorders, 290, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage focus editions. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, T., Kumar, A., Upadhyay, P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2021). Link between social distancing, cognitive dissonance, and social networking site usage intensity: A country-level study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Internet Research, 31(2), 419–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S. R., Schuster, A. M., & Seifert, A. (2022). Social media use and well-being among older adults. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S. A., Kenyon, V., Lagacé, M., Wittich, W., & Southall, K. E. (2016). Stereotypes associated with age-related conditions and assistive device use in Canadian media. The Gerontologist, 56(6), 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, T., Camp, A., Amateau, G., & Iwanaga, K. (2024). Internalized ageism as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 28(4), 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D. (1995). Economic distress and coping behaviors of urban households [Doctoral dissertation, Kyung Hee University]. Available online: https://library.khu.ac.kr/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Jung, J. (2020). The effects of support expectation and policy trust on anxiety about old age for the middle-aged: Focusing on mediating effect of preparation for old age [Doctoral dissertation, Ewha Womans University]. Available online: https://riss.or.kr (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kadoya, Y., Khan, M. S. R., Hamada, T., & Dominguez, A. (2018). Financial literacy and anxiety about life in old age: Evidence from the USA. Review of Economics of the Household, 16, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., & Kim, H. (2022). Ageism and psychological well-being among older adults: A systematic review. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 8, 23337214221087023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Thyer, B. A., & Munn, J. C. (2019). The relationship between perceived ageism and depressive symptoms in later life: Understanding the mediating effects of self-perception of aging and purpose in life, using structural equation modeling. Educational Gerontology, 45(2), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. (2011). A study on anxiety about aging of college students. Korean Journal of Social Welfare Research, 26, 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lasher, K. P., & Faulkender, P. J. (1993). Measurement of aging anxiety: Development of the anxiety about aging scale. The International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 37(4), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Y., Choi, I. H., & Kim, I. S. (2020). Generation conflicts experienced by old men and women and measures for generation cohesion in Korea. Korean Women’s Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(6), 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B. R., Chang, E. S., Lowe, S. R., Provolo, N., & Slade, M. D. (2022). Impact of media-based negative and positive age stereotypes on older individuals’ mental health. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77(4), e70–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. R., Hausdorff, J. M., Hencke, R., & Wei, J. Y. (2000). Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(4), P205–P213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. R., & Leifheit-Limson, E. (2009). The stereotype-matching effect: Greater influence on functioning when age stereotypes correspond to outcomes. Psychology and Aging, 24(1), 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. R., & Myers, L. M. (2004). Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-perceptions of aging. Preventive Medicine, 39(3), 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B. R., Provolo, N., Chang, E. S., & Slade, M. D. (2021). Negative age stereotypes associated with older persons’ rejection of COVID-19 hospitalization. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(2), 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18(3), 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, R. D., Blair, C., Best, P., McGlinchey, E., & Armour, C. (2021). Media consumption and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown: A UK cross-sectional study across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Journal of Public Health, 31, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Pensions at a glance 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2021/12/pensions-at-a-glance-2021_e56e5553.html (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Pedroso-Chaparro, M. del S., Antón-López, J. C., Cabrera, I., Márquez-González, M., Martínez-Huertas, J. Á., & Losada-Baltar, A. (2023). ‘I feel old and have aging stereotypes’. Internalized aging stereotypes and older adults’ mental health: The mediational role of loneliness. Aging & Mental Health, 27(8), 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K. (2018). Cognitive effects of social media use: A case of older adults. Social Media+Society, 4(3), 2056305118787203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y., Hashimoto, T., & Karasawa, K. (2022). Decreasing anti-elderly discriminatory attitudes: Conducting a ‘Stereotype Embodiment Theory’-based intervention. European Journal of Social Psychology, 52(1), 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. (2021). Quality of life indicators in Korea 2020. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/1/index.board?bmode=download&bSeq=&aSeq=388561&ord=11 (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Statistics Korea. (2022). Life tables 2021. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/boardDownload.es?bid=208&list_no=422107&seq=1 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Watkins, R. E., Coates, R., & Ferroni, P. (1998). Measurement of aging anxiety in an elderly Australian population. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 46(4), 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, S., Tesch-Römer, C., & Tomasik, M. J. (2007). Longitudinal findings on aging-related cognitions, control beliefs, and health in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(3), 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, R., Khan, S., Rafiq, M., Fawad, N., Shams, S., Navid, S., Khan, M. A., Taufiq, N., Touqir, A., Imran, M., & Butt, T. A. (2022). Aging is inevitable: Understanding aging anxiety related to physical symptomology and quality of life with the mediating role of self-esteem in adults. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E. Y. (2002). A study of urban housewives financial stress, coping strategies and their economic well-being [Doctoral dissertation, Sookyung Women’s University]. Available online: https://lib.sookmyung.ac.kr/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

| Characteristics | n (%) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 73.77 (5.797) | 65–84 |

| Gender | ||

| Male (=1) | 266 (44.3) | |

| Female (=0) | 334 (55.7) | |

| Region | ||

| Rural city (=1) | 256 (21.3) | |

| Medium-sized city (=2) | 415 (34.6) | |

| Metropolitan city (=3) | 529 (44.1) | |

| Spouse | ||

| With spouse (=1) | 374 (62.3) | |

| Without spouse (=0) | 226 (37.7) | |

| Housing status | ||

| Participant owns a house (=1) | 461 (76.8) | |

| Participant does not own a house (=0) | 139 (23.2) | |

| Occupational Status | ||

| Employed (=1) | 243 (40.5) | |

| Not employed (=0) | 357 (59.5) | |

| Subjective health status (M, SD) | 3.09 (0.908) | 1–5 |

| Subjective economic status (M, SD) | 2.40 (0.681) | 1–5 |

| Measured Variable | Unstandardized Factor Loading | SE | Standardized Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media image | |||

| M1 | 1.000 | ─ | 0.802 |

| M2 | 1.043 | 0.041 | 0.906 |

| M3 | 1.076 | 0.042 | 0.915 |

| Perceived age stereotypes | |||

| S1 | 1.000 | ─ | 0.826 |

| S2 | 1.146 | 0.054 | 0.859 |

| S3 | 1.030 | 0.053 | 0.772 |

| Aging anxiety: financial | |||

| AAF1 | 1.000 | ─ | 0.850 |

| AAF2 | 1.001 | 0.052 | 0.750 |

| AAF3 | 1.017 | 0.048 | 0.820 |

| Aging anxiety: psychosocial | |||

| AAP1 | 1.000 | ─ | 0.791 |

| AAP2 | 1.020 | 0.045 | 0.850 |

| AAP3 | 1.126 | 0.046 | 0.917 |

| (48) = 126.361, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.0246 | |||

| 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|

| Media image → perceived age stereotypes → aging anxiety: financial | [−0.005, 0.081] |

| Media image → perceived age stereotypes → aging anxiety: psychosocial | [0.034, 0.121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, S.; Kim, M.; Jang, Y.; Park, N.S.; Yoon, H. Media Representations of Aging and Their Psychological Impact: Age Anxiety Among Older Korean Adults. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070932

Chung S, Kim M, Jang Y, Park NS, Yoon H. Media Representations of Aging and Their Psychological Impact: Age Anxiety Among Older Korean Adults. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):932. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070932

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Soondool, Miri Kim, Yuri Jang, Nan Sook Park, and Hyunwoo Yoon. 2025. "Media Representations of Aging and Their Psychological Impact: Age Anxiety Among Older Korean Adults" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070932

APA StyleChung, S., Kim, M., Jang, Y., Park, N. S., & Yoon, H. (2025). Media Representations of Aging and Their Psychological Impact: Age Anxiety Among Older Korean Adults. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070932