Microeconomic Losses Due to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women (IPVAW): Three Scenarios Based on Accounting Methodology Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background Literature on the Impacts of IPVAW

1.2. IPVAW Costing Estimation Methodologies

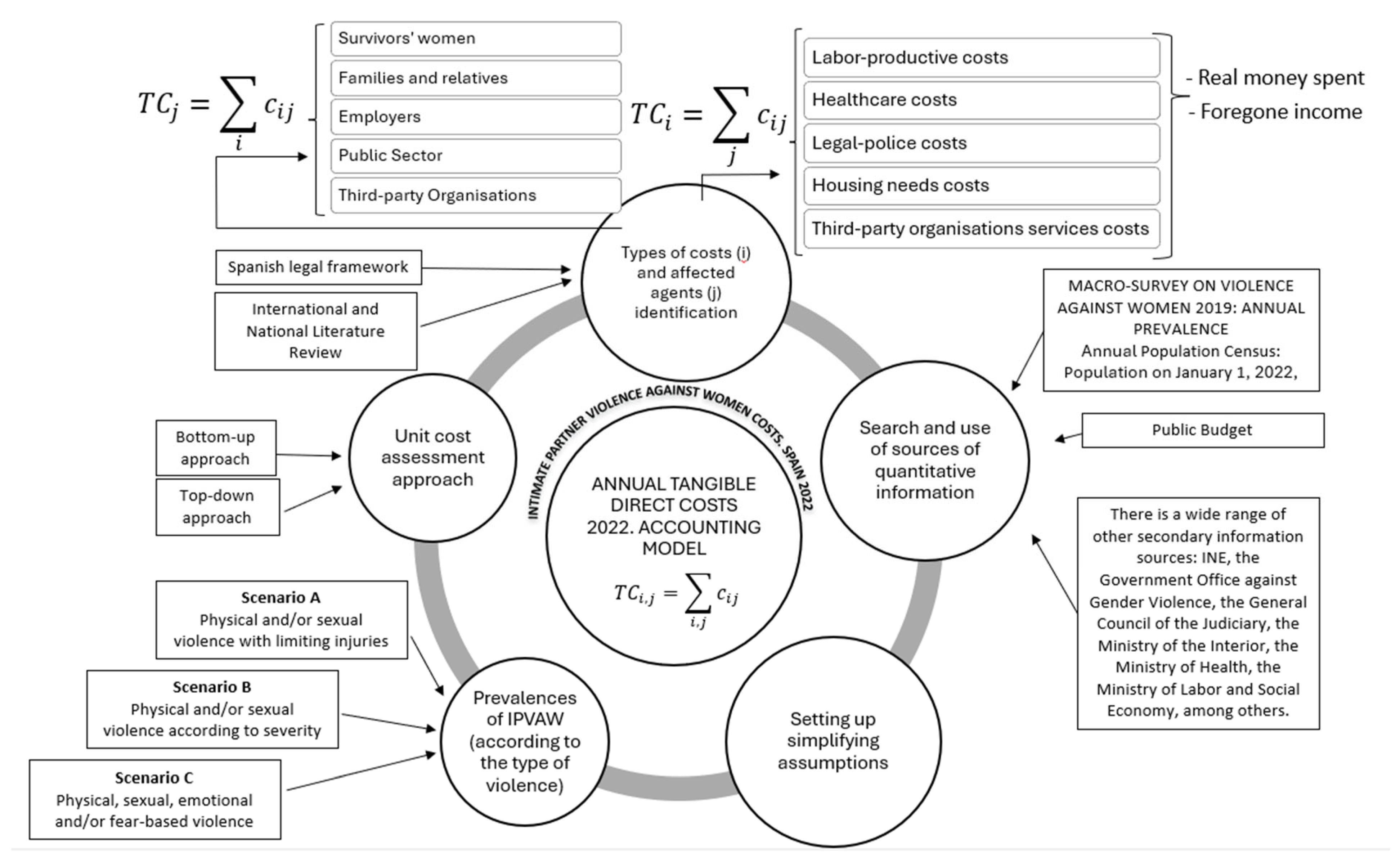

1.3. The Current Research

2. Methodological Issues and Materials

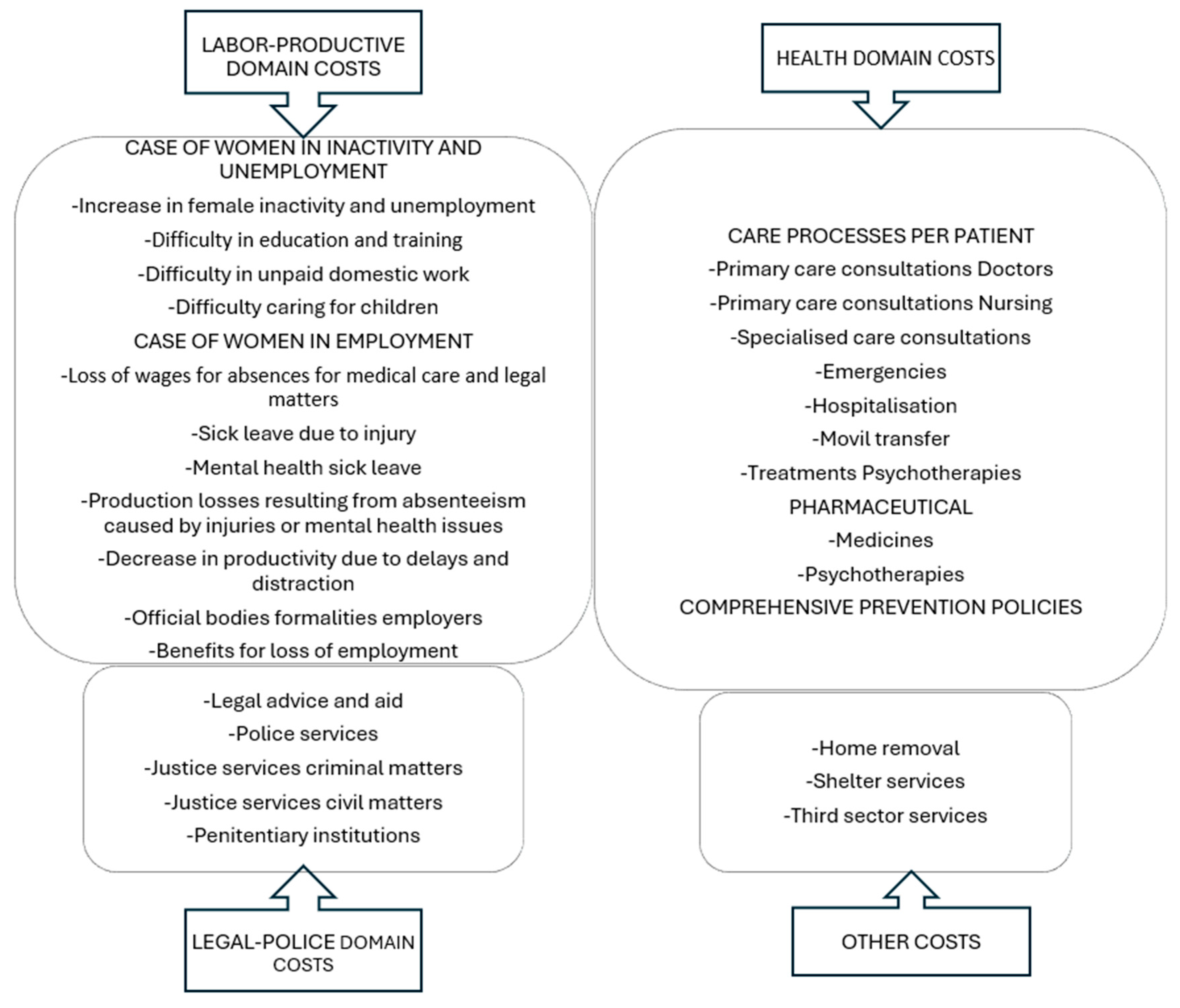

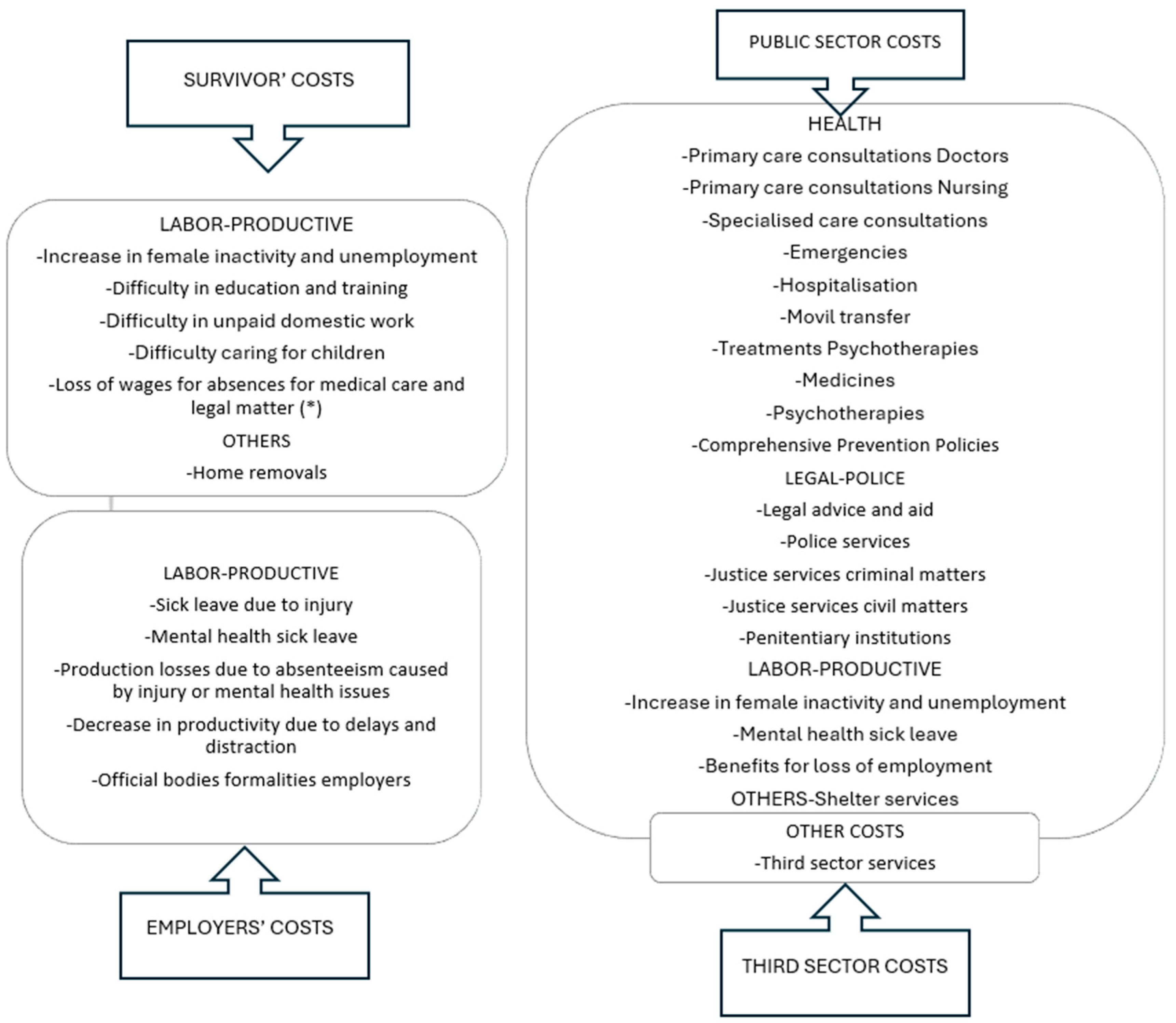

2.1. Microeconomic Approach to IPVAW Costs: General Methodological Aspects

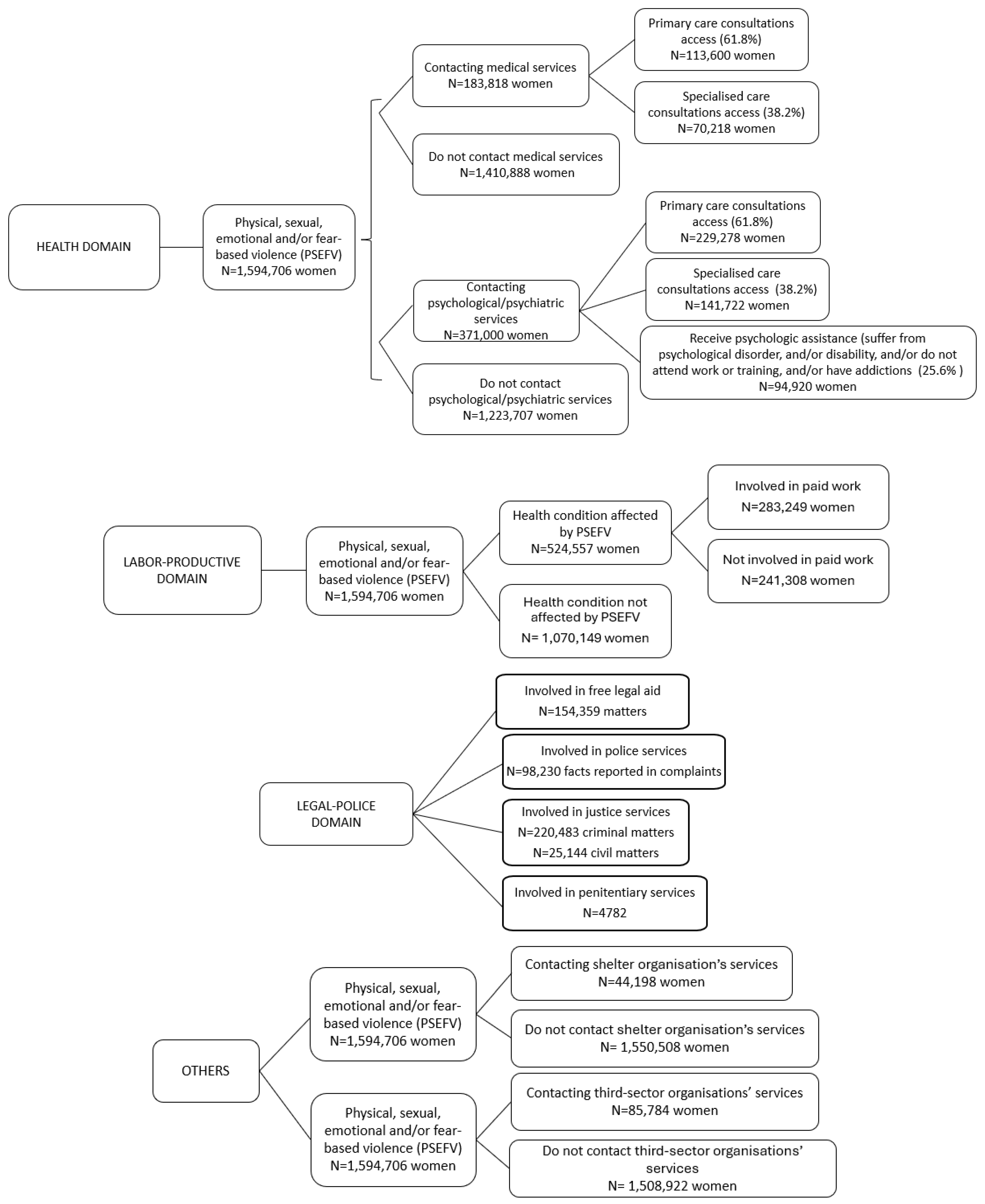

2.2. Specific Methodological Aspects in Each Domain

2.2.1. Healthcare Domain

2.2.2. Legal-Police Domain

2.2.3. Labor-Productive Domain

- Costs due to increased female inactivity and unemployment

- 2.

- Costs due to the difficulties of access to education and training

- 3.

- Costs due to the difficulties in the provision of domestic services

- 4.

- Costs due to difficulties in caring for children

- 5.

- Wage penalty costs for absences due to medical and legal issues.

- 6.

- Costs for sick leave from work due to physical injuries and mental health damages

- 7.

- Costs for loss of production for absences due to physical injury and mental health impairment

- 8.

- Costs for reduced productivity due to delays and distractions at work

- 9.

- Costs for employers’ administrative actions due to absences from work

- 10.

- Cost of benefits paid for job losses

2.2.4. Other Costs

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Results and Public Policy Recommendations

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPVAW | Intimate partner violence against women |

| GVB | Gender-based violence |

| PSV | Physical and/or sexual IPVAW |

| PSEVF | Physical, sexual, and/or emotional IPVAW and/or fear |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DGVG | Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género (Government Office against Gender-Based Violence) |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estadística (The Spanish National Institute of Statistics) |

| EIGE | European Institute for Gender Equality |

| ICRW | International Center for Research on Women |

| MSSSI | Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales, e Igualdad (Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality) |

| NCIP&C | National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (USA) |

| NCRVAW&C | National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (Australia) |

| UNFPA | United Nations Fund Population |

| 1 | In Spain, the first and most important legal norm in this topic was developed in 2004: Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género (Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2024). This law refers to IPVAW as gender-based violence. |

| 2 | For the costs of the legal-police domain, the prevalence of administrative records is considered, which refers to the cases reported and detected by official institutions, generating a demand for services in this area. Institutional prevalences yield much lower figures than the prevalences derived from self-perception surveys, given the low percentage of reports of these forms of violence. |

| 3 | Its first two modules focus on the study of violence against women by current (module 1) or former (module 2) partners. |

| 4 | Emotional violence is a specific type of psychological violence that includes the following behaviours by a partner or former partner: he has insulted you or made you feel bad about yourself; put you down or humiliated you in front of other people; frightened or intimidated you on purpose; verbally threatened to hurt you; verbally threatened to hurt your children or someone else who is important to you; threatened to harm himself if you leave him; threatened to take your children away from you (according to the 2019 Macro-survey). |

| 5 | The Expenditure Programs of the responsible bodies at the state (Ministry of the Interior), regional (for the three Autonomous Communities that have their police forces), and local levels have been reviewed. The amounts of recognized obligations or executed expenditures have been considered whenever possible, and only those corresponding to wages and salaries as well as expenditures on goods and services necessary for the provision of services have been considered. |

| 6 | These ratios are derived from Secretaría de Estado de Presupuestos y Gastos (2023) and Ministerio del Interior (2022). |

| 7 | Catalonia and the Basque Country have also transferred these competencies. |

| 8 | These comparisons should be taken with due caution, as methodologies and concepts are not homogeneous or fully comparable in a strict sense. |

References

- Access Economics. (2004). The cost of domestic violence to the Australian economy. Australian Government under Partnerships Against Domestic Violence. ISBN 1-877-042-74. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. (2024). Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género. «BOE» núm. 313, de 29/12/2004. Available online: https://www.boe.es/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Aguirre Martin Gil, R. (2008). Magnitud, impacto en salud y aproximación a los costes sanitarios de la violencia de pareja hacia las mujeres en la Comunidad de Madrid (Documentos Técnicos de Salud Pública). Servicio Madrileño de Salud y Agencia Laín Entralgo. [Google Scholar]

- Ashe, S., Duvvury, N., Raghavendra, S., Scriver, S., & O’Donovan, D. (2017). Methodological approaches for estimating the economic costs of violence against women and girls (Working Paper). What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls Programme. Available online: http://www.whatworks.co.za/documents/publications/90-methodological-approaches-for-estimating-the-economic-costs-of-vawg (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(5), 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M. C., & Breiding, M. J. (2008). Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviours associated with intimate partner violence—United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57(5), 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, F., Smith, M., Long, J., & O’Dowd, T. (2002). Reported frequency of domestic violence: Cross sectional survey of women attending general practice. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 324(7332), 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarasa i Casals, M. (2009). Propuesta de nuevos indicadores para medir los efectos de la violencia de género. SURT. Fundació de Dones. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalin, C., Albagly, M., Mugnier, C., & Nec-toux, M. (2015). Étude relative à l’actualisation du chiffrage d nvestigaciónons économiques des violences au sein du couple et leur incidence sur les enfants en France en 2012: Rapport final de l’étude. Psytel. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Secretariat. (2019). The economic cost of violence against women and girls: A study of seychelles. Commonwealth Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Secretariat. (2020). The economic cost of violence against women and girls: A study of lesotho. Commonwealth Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Secretariat. (2022). Measuring the economic cost of violence against women and girls. Facilitator’s guide. Commonwealth Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Comunidad de Madrid. (2023). Díaz Ayuso anuncia que la Comunidad de Madrid bajará los precios de FP Superior según los resultados académicos de los alumnos. Noticias, 21 de junio de 2023. Available online: https://www.comunidad.madrid/noticias/2023/06/21/diaz-ayuso-anuncia-comunidad-madrid-bajara-precios-fp-superior-resultados-academicos-alumnos (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Consejo General del Poder Judicial. (n.d.). Liquidación de presupuestos de las comunidades autónomas. Datos consolidados. Áreas y políticas de gasto: Servicios públicos básicos: JUSTICIA. Ejercicio 2020. Poder Judicial de España. Available online: https://www.poderjudicial.es/cgpj/es/Temas/Estadistica-Judicial/Estadistica-por-temas/Aspectos-economicos-de-la-justicia/Presupuestos/Liquidacion-de-Presupuestos-de-las-Comunidades-Autonomas/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Consejo General del Poder Judicial. (2023). La Justicia dato a dato. Año 2022. Estadística Judicial. Consejo General del Poder Judicial. Available online: https://www.poderjudicial.es/stfls/ESTADISTICA/FICHEROS/JusticaDatoaDato/Justicia%20Dato%20a%20Dato%202022.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Council of Europe. (2012/2014). Overview of studies on the costs of violence against women and domestic violence. Strasbourg. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168059aa22 (accessed on 3 March 2025). (Original work published 2012).

- Cruz Roja Española. (2017). Las mujeres víctimas de violencia de género atendidas en el Servicio Atenpro. Boletín sobre Vulnerabilidad Social. [Google Scholar]

- DGVG. (2020). Macroencuesta de violencia contra la mujer. Ministerio de Igualdad. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/wp-content/uploads/Macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Dubourg, R., Hamed, J., & Thorns, J. (2005). The economic and social costs of crime against individuals and households 2003/04 (Home Office, Online Report 30/05). Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/191498/Green_Book_supplementary_guidance_economic_social_costs_crime_individuals_households.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Duvvury, N., Callan, P., Carney, P., & Raghavendra, S. (2013). Intimate partner violence: Economic costs and implications for growth and development (n° 3). Women’s Voice, Agency, and Participation Research Series. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Duvvury, N., Carney, P., & Minh, N. H. (2012). Estimating the cost of domestic violence against women in Vietnam. UN Women. [Google Scholar]

- Duvvury, N., Grown, C., & Redner, J. (2004). Costs of intimate partner violence at the household and community levels. An operational framework for developing countries. International Center for Research on Women (ICRW). [Google Scholar]

- EIGE. (2014). Estimating the cost of gender-based violence in the European Union (European Institute for Gender Equality, S. Walby, & P. Olive, Eds.). Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- EIGE. (2021). The costs of gender-based violence in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIGE. (2023). Understanding intimate partner violence in the European Union The essential need for administrative data collection. Publication date 15 February 2023. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/publications/understanding-intimate-partner-violence-european-union-essential-need-administrative-data-collection (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Envall, E., & Eriksson, A. (2006). Costs of violence against women (English Summary). Available online: https://gender-financing.unwomen.org/en/resources/c/o/s/costs-of-violence-against-women (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- European Parliamentary Research Services. (2021). Combating gender-based violence: Cyber violence. European Added Value Unit (PE 662.621—March 2021). European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, C., Jansen, H., Ellsberg, M., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2005). WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Heeks, M., Reed, S., Tafsiri, M., & Prince, S. (2018). The economic and social costs of crimen. Home Office, Gov. UK Ed., 2nd ed. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60094b86d3bf7f2ab1a1af96/the-economic-and-social-costs-of-crime-horr99.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Hegarty, K., Gunn, J., Chondros, P., & Taft, A. (2008). Physical and social predictors of partner abuse in women attending general practice: A cross-sectoral study. British Journal of General Practice, 58(552), 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heise, L. (1996). Violence against women: Global organizing for change. In J. L. Edleson, & Z. C. Eisikovits (Eds.), Future interventions with battered women and their families (pp. 7–33). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, L. M., Trevillion, K., Khalifeh, H., Woodall, A., Agnew-Davies, R., & Feder, G. (2010). Domestic violence and severe psychiatric disorders: Prevalence and interventions. Psychological Medicine, 40(6), 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICRW. (2009). Intimate partner violence: High costs to households and communities. ICRW. [Google Scholar]

- Intervención General de la Administración del Estado. (2023). Estadísticas de ejecución del presupuesto. Provisional. Diciembre 2022. Available online: https://www.igae.pap.hacienda.gob.es/sitios/igae/es-ES/Contabilidad/ContabilidadPublica/CPE/EjecucionPresupuestaria/Documents/12-MENSUAL%2012-22.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Jaitman, L., & Torre, I. (2017). Estimación de los costos directos del crimen y la violencia. In L. Jaitman (Ed.), Los costos del crimen y de la violencia: Nueva evidencia y hallazgos en América Latina y el Caribe (pp. 19–52). BID. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes, R. (2010). Emotional abuse: A neglected dimension of partner violence. The Lancet, 376(9744), 851–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KPMG. (2014). Too costly to ignore. The economic impact of gender-based violence in South Africa. KPMG Human and Social Services. [Google Scholar]

- Mañas-Alcón, E., & Gallo-Rivera, M. T. (2020). La violencia económica en el ámbito de la pareja: Otra forma de violencia que perpetúa la desigualdad de género en España. In Mujeres y economía. La brecha de género en el ámbito económico y financiero (pp. 107–148). ISBN/ISSN: 978-84-92546-58-9, NIPO: 094-20-029-7. Secretaría General Técnica; Centro de Publicaciones; Ministerio de Economía, Comercio y Empresa. [Google Scholar]

- Mañas-Alcón, E., Gallo-Rivera, M. T., Rivera-Galicia, L., Montes-Pineda, O., Figueroa-Navarro, C., Castellano-Arroyo, M., Pérez-Troya, A., Montalvo-García, G., Prego-Meleiro, P., Cámara-Sánchez, A., Lastres-Gómez, F., Recalde-Esnoz, I., & Perea-Rodríguez, R. (2024). Impacto de la violencia de género y de la violencia sexual contra las mujeres (II): Una valoración de sus costes en 2022. Ministerio de Igualdad. NIPO: 048-24-002-4. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/wp-content/uploads/Costes_VG_VSFP_2022.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025)NIPO: 048-24-002-4.

- Mañas-Alcón, E., Rivera-Galicia, L., Gallo-Rivera, M., Montes-Pineda, O., Figueroa-Navarro, C., Castellano-Arroyo, M., & Prieto-Sánchez, P. (2019). El impacto de la violencia de género en España: Una valoración de sus costes en 2016. Ministerio de la Presidencia, Relaciones con las Cortes e Igualdad. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez León, M. (2015). Valoración médico-legal de la violencia: De la violencia intrafamiliar a la violencia de género. Anales de la Real Academia de Medicina y Cirugía de Valladalid, 52, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Martín, M. I., Marcos Sánchez, A., Sánchez Galindo, M., Villagómez Morales, E., & Sanjuán María, A. M. (2004). Los costes sociales y económicos de la violencia contra las mujeres en Andalucía. Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, J., Kern, D. E., Kolodner, K., Dill, L., Schroeder, A. F., DeChant, H. K., Ryden, J., Bass, E. B., & Derogatis, L. R. (1995). The battering syndrome—Prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary-care internal medicine practices. Annals of Internal Medicine, 123(10), 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio del Interior. (2022). Anuario estadístico del ministerio del interior 2021. Ministerio del Interior. Secretaría General Técnica. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/pdf/archivos-y-documentacion/documentacion-y-publicaciones/anuarios-y-estadisticas/anuarios-estadisticos-anteriores/anuario-estadistico-de-2021/Anuario-Estadistico-2021_web.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Ministerio de Sanidad. (2023). Informe anual violencia de género 2023. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/equidad/Informe_VG_2023_v8.10.2024_final.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- MSSSI. (2012). Protocolo común para la actuación sanitaria ante la VG. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad (MSSSI), Gobierno de España. [Google Scholar]

- MSSSI. (2017). Boletín estadístico anual de violencia de género 2016. Delegación del Gobierno para la VG. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2003). Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/6543/cdc_6543_DS1.pdf? (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children. (2009). The cost of violence against women and their children. The National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 978-1-921380-31-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nectoux, M., Mugnier, C., Baffert, S., Albagly, M., & Thélot, B. (2010). Évaluation économique des violences conjugales en France [An economic evaluation of intimate partner violence in France]. Santé Publique, 22, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Néréa, C., Auberty, K., Chrétiennot, J., Guiraud, C., Mailfert, A. C., Oderda, M., Vignoud, M., Ronai, E., Baba-Aissa, F., Brisard, M., Duquesne, M., Gaudin, P., Jégou, S., Lê, G., Muracciole, M., Nefesh-Clarke, L., & Toledo, L. (2018). Où est l’argent contre les violences faites aux femmes? [Where is the money for combating violence against women?]. Haut Conseil à l’Égalité Entre les Femmes et les Hommes. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio de Justicia Gratuita. (2023). XVII informe del observatorio de justicia gratuita. Estadística completa 2018–2022. Abogacía Española-ARANZADI LA LEY. Available online: https://www.abogacia.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/XVII-Informe-del-Observatorio-de-la-Justicia-Gratuita.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Observatorio del Sistema Universitario. (2016). ¿Por qué precios tan distintos? Precios y tasas en las universidades públicas en España (curso 2016/2017). Diciembre. [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein, P. (2017). The price of violence: Consequences of violent crime in Sweden (Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy (IFAU) Ed.). Working Paper Series, No 2017:22. Available online: https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2017/wp2017-22-the-price-of-violence-consequences-of-violent-crime-in-sweden.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Piispa, M., & Heiskanen, M. (2000). The costs of men’s violence against women in Finland. Council for Equality, Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Rachana, C., Suraiya, K., Hisham, A., Abdulaziz, A., & Hai, A. (2002). Prevalence and complications of physical violence during pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 103(1), 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavendra, S., Duvvury, N., & Ashe, S. (2017). The macroeconomic loss due to violence against women: The case of Vietnam. Feminist Economic, 23(4), 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, C., & O’Leary-Kelly, A. (2007). The Effects and Costs of Intimate Partner Violence for Work Organizations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(3), 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J., Coid, J., Petruckevitch, A., Chung, W. S., Moorey, S., & Feder, G. (2002). Identifying domestic violence: Cross sectional study in primary care. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 324(7332), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Estado de Presupuestos y Gastos. (2023). Presupuesto por programas y memoria de objetivos de 2022. Tomo VI ministerio del interior. Ministerio de Hacienda y Función Pública. Available online: https://www.sepg.pap.hacienda.gob.es/Presup/PGE2023Ley/MaestroTomos/PGE-ROM/doc/L_23_E_G6.PDF (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Secretaría General de Instituciones Penitenciarias. (n.d.). Datos estadísticos de la población reclusa. Anexos. Diciembre 2022. Ministerio del Interior. Available online: https://www.institucionpenitenciaria.es/documents/20126/890869/DICIEMBRE+2022.pdf/ca24084c-4db1-8fa9-df0d-e6446f2cc7d9?version=1.0 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Servicio Murciano de Salud Pública. (2010). Guía Práctica Clínica: Actuación en salud mental con mujeres maltratadas por su pareja. Servicio Murciano de Salud, Consejería de Sanidad y Consumo, Salud Mental. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, D. J., & Nash, K. R. (2007). Acute injury patterns of intimate partner violence victims. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 8(3), 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souto-Nieves, G. (2003). Tasas de descuento para la evaluación de inversiones públicas: Estimaciones para España (P. T. N° 8/03). Instituto de Estudios Fiscales. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, S., Fliedner, J., Schwab, S., & Iten, R. (2013). Costs of intimate partner violence. Federal Office for Gender Equality; FOGE. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckl, H., Devries, K., Rotstein, A., Abrahams, N., Campbell, J., Watts, C., & García-Moreno, C. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review. The Lancet, 382(9895), 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFPA. (2015). The Egypt economic cost of gender-based violence survey (ECGBVS) 2015. United Nations Population Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A. (2013). Los costos empresariales de la violencia contra las mujeres en el Perú. Una estimación del impacto de la violencia contra la mujer en relaciones de pareja en la productividad laboral de las empresas peruanas. Universidad San Martín de Porres. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A. (2015a). Los costos de la violencia contra las mujeres en las microempresas formales peruanas. Una estimación de su impacto económico. Universidad San Martín de Porres. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A. (2015b). Los costos empresariales de la violencia contra las mujeres en Bolivia. Una estimación del impacto invisible para la productividad de la violencia contra las mujeres en relaciones de pareja. Universidad San Martín de Porres. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A. (2015c). Modelo de gestión para prevenir la violencia contra las mujeres. Una propuesta integral para involucrar a las empresas en la prevención de la violencia contra las mujeres en relaciones de pareja. Universidad San Martín de Porres. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A. (2016). Impacto de la violencia contra las mujeres en la productividad laboral Una comparación internacional entre Bolivia, Paraguay y Perú. Universidad San Martín de Porres. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, A., Santi, I., Asencios, Z., & Lescano, G. (2017). Impacto de la violencia contra las mujeres en el desempeño laboral docente en la Región Callao-Perú. USMP & GIZ. [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S. (2004). The costs of domestic violence. Women and Equality Unit, University of Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S., Bell, P., Bowstead, J., Feder, G., Fraser, A., Herbert, A., Kirby, S., McManus, S., Morris, S., Oram, S., Phoenix, J., Pullerits, M., & Verrall, R. (2020). Study on the economic, social and human costs of trafficking in human beings within the EU. European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S., & Olive, P. (2014). Estimating the costs of gender-based violence in the European Union. Project report. European Institute for Gender Equality; Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. (2009). The battered woman syndrome (3rd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (1996). 49a Asamblea Mundial de la Salud, Ginebra, 20–25 de mayo de 1996: Actas resumidas e informes de las comisiones. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/203897 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- WHO. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85239 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- WHO. (2021a). Violence against women. Newsroom. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- WHO. (2021b). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/341337/9789240022256-eng.pdf?sequence= (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Willman, A. (2009). Valuing the impacts of domestic violence: A review by sector. Conflict, Crime and Violence Team; Social Development Department; The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., Hoddenbagh, J., McDonald, S., & Scrim, K. (2012). An estimation of the economic impact of spousal violence in Canada, 2009. Canada, Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

| IPVAW Costs: Three Modeling Scenarios | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||||

| EUR Million | % | EUR Million | % | EUR Million | % | |

| Healthcare | 409.91 | 29.7 | 409.91 | 20.2 | 969.61 | 32.2 |

| Legal-police | 733.10 | 53.2 | 1121.80 | 55.2 | 1121.80 | 37.2 |

| Labor-productive | 156.85 | 11.4 | 423.71 | 20.8 | 585.14 | 19.4 |

| Other costs | 78.41 | 5.7 | 78.41 | 3.9 | 338.05 | 11.2 |

| Total Tangible Costs | 1378.27 | 100 | 2033.83 | 100 | 3014.61 | 100 |

| Total tangible costs (% of GDP) | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.22 | |||

| Tangible costs per person (EUR) | 29 | 43 | 64 | |||

| GDP and population data for Spain | ||||||

| GDP of Spain at current prices 2022 (EUR million) | 1,373,627 * | |||||

| Population of Spain (people) | 47,432,805 | |||||

| Survivor Women | Families and Relatives | Employers | Public Sector | Third Sector-Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | 969,609,866 | ||||

| Legal-police | 1,121,802,198 | ||||

| Labor-productive | 216,807,479 | 49,177,350 | 149,514,445 | 169,645,360 | |

| Other costs | 30,629,214 | 300,420,794 | 6,999,374 | ||

| Total Tangible Costs | 247,436,693 | 49,177,350 | 149,514,445 | 2,561,478,218 | 6,999,374 |

| % of total | 8.2 | 1.6 | 5.0 | 85.0 | 0.2 |

| Amounts (EUR) | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Care Processes per Patient | 739,661,522 | 76.3 |

| A.1. Primary Care Consultations | 82,963,520 | 8.6 |

| - Doctors | 72,937,005 | 7.5 |

| - Nursing | 10,026,516 | 1.0 |

| A.2. Specialized Care Consultations | 599,720,194 | 61.9 |

| - Outpatient consultations | 30,480,096 | 3.1 |

| - Emergencies | 34,168,630 | 3.5 |

| - Hospitalization | 527,650,227 | 54.4 |

| - Mobile transfer | 7,421,241 | 0.8 |

| A.3. Treatments Psychotherapies | 56,977,807 | 5.9 |

| B. Pharmaceutical Costs | 18,716,015 | 1.9 |

| C. Prevention policies | 211,232,330 | 21.8 |

| Total Healthcare Domain | 969,609,866 | 100.0 |

| Amounts (EUR) | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Legal advice and aid | 31,013,818 | 2.8 |

| Police services | 804,919,386 | 71.8 |

| Justice services | 146,922,792 | 13.1 |

| Criminal matters | 132,169,256 | 11.8 |

| Civil matters | 14,753,536 | 1.3 |

| Penitentiary institutions | 138,946,202 | 12.4 |

| Total Legal-Police Domain | 1,121,802,198 | 100.0 |

| Amounts (EUR) | % of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Women in Inactivity and Unemployment | ||

| Increase in females dropping out of the workforce and unemployment | 131,376,557 | 22.5 |

| Difficulty in education and training | 3,162,161 | 0.5 |

| Difficulty in unpaid domestic work | 21,211,597 | 3.6 |

| Difficulty caring for children | 23,007,647 | 3.9 |

| Women in Employment | ||

| Loss of wages for absences due to medical care and legal matters | 125,065,685 | 21.4 |

| Sick leave due to injury | 11,367,220 | 1.9 |

| Mental health sick leave | 191,514,898 | 32.7 |

| Production losses due to absenteeism | 9,738,342 | 1.7 |

| Decrease in productivity | 43,676,541 | 7.5 |

| Official bodies’ formalities for employers | 17,575,121 | 3.0 |

| Benefits for loss of employment | 7,448,865 | 1.3 |

| Total Labor-Productive Domain | 585,144,634 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mañas-Alcón, E.; Gallo-Rivera, M.-T.; Rivera-Galicia, L.-F.; Montes-Pineda, Ó. Microeconomic Losses Due to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women (IPVAW): Three Scenarios Based on Accounting Methodology Approach. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070914

Mañas-Alcón E, Gallo-Rivera M-T, Rivera-Galicia L-F, Montes-Pineda Ó. Microeconomic Losses Due to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women (IPVAW): Three Scenarios Based on Accounting Methodology Approach. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):914. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070914

Chicago/Turabian StyleMañas-Alcón, Elena, María-Teresa Gallo-Rivera, Luis-Felipe Rivera-Galicia, and Óscar Montes-Pineda. 2025. "Microeconomic Losses Due to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women (IPVAW): Three Scenarios Based on Accounting Methodology Approach" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070914

APA StyleMañas-Alcón, E., Gallo-Rivera, M.-T., Rivera-Galicia, L.-F., & Montes-Pineda, Ó. (2025). Microeconomic Losses Due to Intimate Partner Violence Against Women (IPVAW): Three Scenarios Based on Accounting Methodology Approach. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070914