Perceiving Speaker’s Certainty: The Interaction Among Subjectivity of Statement, Evidential Markers, and Evidence Strength

Abstract

1. Introduction

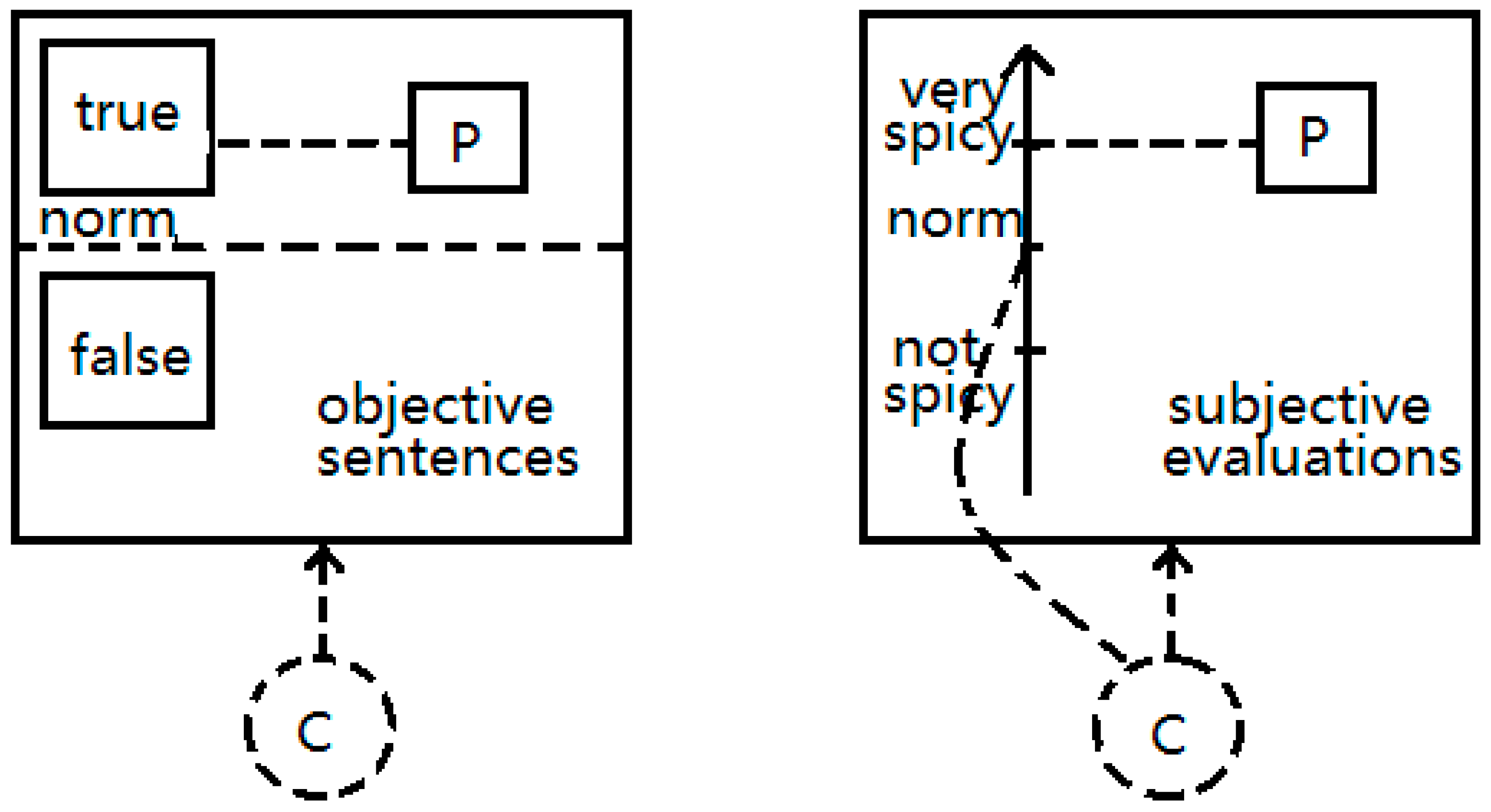

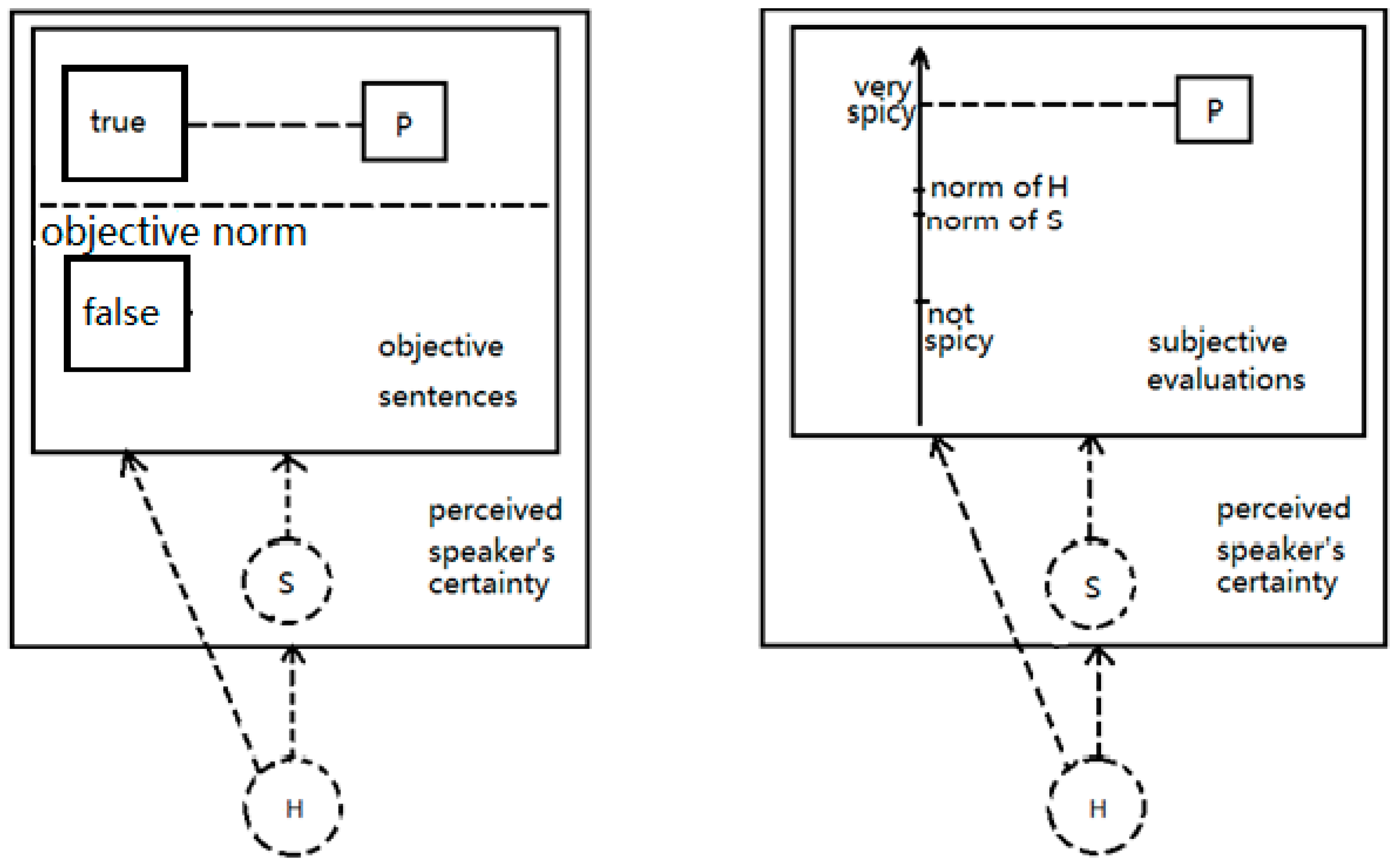

1.1. Subjective/Objective Statements and Speaker’s Certainty

| (1) 卧室 门 开 了。 |

| wòshì mén kāi le |

| bedroom door open -ed |

| The door of the bedroom has opened. |

| (2) 这道 菜 很 好吃。 |

| zhèdào cài hěn hǎochī |

| this dish very delicious |

| This dish is very delicious. |

1.2. The Role of Evidentiality in Modulating (Perceived) Speaker’s Certainty

1.3. Chinese Evidential Markers

| (3) 我 看见/ 想/ 听说 外面 在 下雨。 |

| wǒ kànjiàn/ xiăng/ tīngshuō wàimiàn zài xiàyǔ |

| I see/think/hear outside -ing rain |

| I see/think/hear it is raining outside. |

| (4) 依 我 看/ 推断/ 听说, 那 不 是 真的。 |

| yī wǒ kàn/ tuīduàn/ tīngshuō, nà bù shì zhēnde |

| according I see/infer/hear, that not be true |

| According to me/based on my inference/from what I hear, that is not true. |

| (5) 我 估计 卧室 门 开 了。 |

| wǒ gūjì wòshì mén kāi le |

| I reckon bedroom door open -ed |

| I reckon the door of the bedroom has opened. |

| (6) 我 估计 这道 菜 很 好吃 |

| wǒ gūjì zhèdào cài hěn hàochī |

| I reckon this dish very delicious |

| I reckon this dish is very delicious. |

1.4. Evidence Strength and Speaker’s Certainty

| (7) Conditional: The democratic government of Afghanistan is embroiled in a protracted conflict with Taliban insurgents. The European Union recently pledged 9000 troops to provide added security in population centers. How likely is it that Afghanistan will have a stable government in 5 years? |

| (8) Marginal: The democratic government of Afghanistan is embroiled in a protracted conflict with Taliban insurgents. How likely is it that Afghanistan will have a stable government in 5 years? |

1.5. The Present Study

2. Experiment 1: Speaker’s Certainty with No Evidence Given in the Context

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Materials

Selection of Chinese Evidential Markers

Construction of Critical Sentences

Experimental Stimuli

| (9) | Objective-bare | ||||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 爸爸 | 在 | 客厅 | 沙发 | 上 | 睡觉, | ||||

| nǐ | hé | bàbà | zài | kétīng | shāfā | shàng | shuìjiào | ||||

| you | and | dad | in | living room | sofa | on | sleep | ||||

| 爸爸 | 对 | 你 | 说: | “卧室 | 门 | 开 | 了”。 | ||||

| bàbà | duì | nǐ | shuō | wòshì | mén | kāi | le | ||||

| dad | to | you | say | bedroom | door | open | -ed | ||||

| ‘You and your dad are sleeping on the sofa in the living room. Your dad says to you: The bedroom door has opened.’ | |||||||||||

| (10) | Objective-marked | ||||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 爸爸 | 在 | 客厅 | 沙发 | 上 | 睡觉, | ||||

| nǐ | hé | bàbà | zài | kétīng | shāfā | shàng | shuìjiào | ||||

| you | and | dad | in | living room | sofa | on | sleep | ||||

| 爸爸 | 对 | 你 | 说: | “我 | 估计 | 卧室 | 门 | 开 | 了”。 | ||

| bàbà | duì | nǐ | shuō | wǒ | gūjì | wòshì | mén | kāi | le | ||

| dad | to | you | say | I | reckon | bedroom | door | open | -ed | ||

| ‘You and your dad are sleeping on the sofa in the living room. Your dad says to you: I reckon the bedroom door has opened.’ | |||||||||||

| (11) | Subjective-bare | ||||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 爸爸 | 今天 | 要 | 在 | 饭店 | 请 | 客人 | 吃饭, | ||

| nǐ | hé | bàbà | jintiān | yào | zài | fàndiàn | qǐng | kérén | chīfàn, | ||

| you | and | dad | today | will | in | restaurant | treat | guest | have meal | ||

| 你们 | 来到 | 饭店, | 爸爸 | 对 | 你 | 说: | “这个 | 菜 | 很 | 好吃”。 | |

| nǐmén | láidào | fàndiàn | bàbà | duì | nǐ | shuō | zhègè | cài | hěn | hǎochī | |

| you | come to | restaurant | dad | to | you | say | this | dish | very | delicious | |

| ‘You and your dad plan to treat some guests in the restaurant today. When you arrive at the restaurant, your dad tells you: This dish is very delicious.’ | |||||||||||

| (12) | Subjective-marked | ||||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 爸爸 | 今天 | 要 | 在 | 饭店 | 请 | 客人 | 吃饭, | ||

| nǐ | hé | bàbà | jintiān | yào | zài | fàndiàn | qǐng | kérén | chīfàn, | ||

| you | and | dad | today | will | in | restaurant | treat | guest | have meal | ||

| 你们 | 来到 | 饭店, | 爸爸 | 对 | 你 | 说: | “我 | 估计 | 这个 | 菜 | |

| nǐmén | láidào | fàndiàn, | bàbà | duì | nǐ | shuō | wǒ | gūjì | zhègè | cài | |

| you | come to | restaurant | dad | to | you | say | I | reckon | this | dish | |

| 很 | 好吃。” | ||||||||||

| hěn | hǎochī | ||||||||||

| very | delicious | ||||||||||

| ‘You and your dad plan to treat some guests in the restaurant today. When you arrive at the restaurant, your dad tells you: I reckon this dish is very delicious.’ | |||||||||||

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Results

2.3. Discussion

3. Experiment 2: Perception of Speaker’s Certainty with Provided Evidence

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Materials

| (13) | Objective sentences with a piece of evidence | |||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 爸爸 | 在 | 客厅 | 沙发 | 上 | 睡觉, | |||

| nǐ | hé | bàbà | zài | kétīng | shāfā | shàng | shuìjiào | |||

| you | and | dad | stay | living room | sofa | on | sleep | |||

| 爸爸 | 听到 | 了 | 开门 | 的 | 声音, | 对 | 你 | 说: | “卧室 | |

| bàbà | tīngdào | le | kāimén | de | shēngyīn | duì | nǐ | shuō | wòshì | |

| dad | hear | -ed | open door | ‘s | sound | to | you | sya | bedroom | |

| 门 | 开 | 了”。 | ||||||||

| mén | kāi | le | ||||||||

| door | open | -ed | ||||||||

| ‘You and your dad are sleeping on the sofa in the living room. Hearing the sound of the door opening, your dad says to you: The door of the bedroom has opened. | ||||||||||

| (14) | Subjective statements with a piece of evidence | |||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 爸爸 | 今天 | 要 | 在 | 饭店 | 请 | 客人 | 吃饭, | |

| nǐ | hé | bàbà | jintiān | yào | zài | fàndiàn | qǐng | kérén | chīfàn, | |

| you | and | dad | today | will | in | restaurant | treat | guest | have meal | |

| 你们 | 来到 | 饭店, | 爸爸 | 看 | 了 | 一下 | 菜品 | 照片, | ||

| nǐmén | láidào | fàndiàn, | bàbà | kàn | le | yíxià | càipǐn | zhàopiàn | ||

| you | come to | restaurant, | dad | see | -ed | once | dish | picture | ||

| 对 | 你 | 说: | “这个 | 菜 | 很 | 好吃”。 | ||||

| duì | nǐ | shuō | zhègè | cài | hěn | hăochī | ||||

| to | you | say | this | dish | very | delicious | ||||

| You and your dad plan to treat some guests in the restaurant today. At the restaurant, after checking the pictures of the dishes, your dad tells you: This dish is very delicious. | ||||||||||

| (15) | 假设 | 一个人 | 在 | 客厅 | 睡觉, | 听到 | 了 开 | 门 | 的 | 声音, |

| jiǎrú | yígèrén | zài | kétīng | shuìjiào | tīngdào | le kāi | mén | de | shēngyīn | |

| suppose | a person | in | restaurant | sleep | hear | -ed open | door | ‘s | sound | |

| 你 | 觉得 | 这个 | 人 | 得到 | “卧室 | 门 | 开 了” | 这个 | 结论 | |

| nǐ | juédé | zhègè | rén | dédào | wòshì | mén | kāi le | zhègè | jiélùn | |

| you | think | this | person | get | bedroom | door | open -ed | this | conclusion | |

| 的 | 可能性 | 有 | 多 | 大? | ||||||

| de | kénéngxìng | yǒu | duōdà | |||||||

| ‘s | probability | have how | big | |||||||

| Suppose a person is sleeping in the living room and hears the sound of a door opening. What do you think is the likelihood of this person concluding that the bedroom door is open? | ||||||||||

3.1.3. Procedure

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Evidential Markers on the Perceived Speaker Certainty

| (16) | 举例来说, | 六十四 | 卦 | 的 | 第一 | 卦, | 乾卦, | 据说 | 是 | |

| jǔlì láishuō | liùshísì | guà | de | dìyī | guà | qiánguà | jùshuō | shì | ||

| for instance | 64 | hexagram | ‘s | first | hexagram | Qian hexagram | reportedly | be | ||

| 刚健 | 之 | 象; | 第二卦, | 坤卦, | 是 | 柔顺 | 之 | 象。 | ||

| gāngjiàn | zhī | xiàng | dì‘érguà | kunguà | shì | róushùn | zhī | xiàng | ||

| strength | and | vigor of image | second | Kun hexagram | be | gentle | of | image | ||

| 凡是 | 满足 | 刚健 | 条件 | 的 | 事物,都 | 可以 | 代入 | 有 | 乾卦 | |

| fánshì | mănzú | gāngjiàn | tiáojiàn | de | shìwù dōu | kěyǐ | dàirù | yŏu | qián’guà | |

| every | meet | strength and vigor | condition | ‘s | thing all | may | bring | into | Qián | |

| 卦象 | 出现 的 | 公式 | 里;凡是 | 满足 | 柔顺 | 条件 | 的 | 事物, | ||

| guàxiàng | chūxiàn de | gōngshì | lĭ fánshì | mănzú | róushùn | tiáojiàn | de | shìwù | ||

| hexagram | appear ‘s | formula | in every | meet | docility | condition | ‘s | thing | ||

| 都 | 可以 | 代入 有 | 坤卦 | 卦象 | 出现 | 的 | 公式 | 里。 | ||

| dōu | kěyǐ | dàirùyŏu | kūn’guà | guàxiàng | chūxiàn | de | gōngshì | lĭ | ||

| all | may | bring into have | Kun hexagram | hexagram | appear | ‘s | formula | in |

4.2. Modulation of Subjectivity of Statement on the Effect of Evidential Markers

| (17) Contexts without evidence: | |||||||||

| 你 | 和 | 张三 | 被 | 困 | 在 | 战壕 | 中, 商量 | 突围 | 时间, |

| nĭ | hé | Zhāng Sān | bèi | kùn | zài | zhànháo | zhōng, shāngliáng | tūwéi | shījiān, |

| you | and | Zhang San | -ed | trap | stay | trench middle | discuss | breakout | time |

| You | and | Zhang San | are | trapped | in the | trench, | discussing about the | breakout | time. |

| 张三 | 对 | 你 | 说: | “这个 | 时间 | 非常 | 适合。” | ||

| Zhāng Sān | duì | nǐ | shuō | zhègè | shíjiān | fēicáng | héshì | ||

| Zhang San | to | you | say | this | time | very | suitable | ||

| Zhang San says to you: This time is very suitable. | |||||||||

4.3. Interaction Among Subjectivity, Evidential Markers, and Evidence Strength

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

| (18) | a. 我认为我高攀了你们家。 |

| I think I have climbed high in your family. | |

| b. 最后这一推论相当合理, 我认为。 | |

| This conclusion seems quite reasonable, I think. | |

| c. 回顾三年来的工作, 我认为, 文艺界是很有成绩的部门之一。 | |

| Looking back on the work of the past three years, I think, the cultural and artistic circles have been one of the most successful sectors. |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The 18 Bare Objective Sentences and Their Evidential Forms Adopted in Experiment 1

| Objective | Subjective | |||

| Bare | With Marker | Bare | With Marker | |

| 1 | 红灯亮了。 The red light is on. | 我认为红灯亮了。 I think the red light is on. | 那个孩子非常聪明。 That child is very clever. | 我认为那个孩子非常聪明。 I think that child is very clever. |

| 2 | 米饭烧糊了。 The rice was burned. | 我认为米饭烧糊了。 I think the rice was burnt. | 这个学生非常认真。 This student is very careful. | 我认为这个学生非常认真。 I think this student is very careful. |

| 3 | 外面下雨了。 It is raining outside. | 我认为外面下雨了。 I think it is raining outside. | 这个手机很好用。 This phone functions very well. | 我认为这个手机很好用。 I think this phone functions very well. |

| 4 | 何鹏进屋了。 He Peng entered the room. | 我以为何鹏进屋了。 I think He Peng entered the room. | 这个城市很大。 This city is very big. | 我以为这个城市很大。 I think this city is very big. |

| 5 | 面包吃光了。 The bread has been eaten up. | 我以为面包吃光了。 I think the bread has been eaten up. | 那台电脑速度非常快。 That computer is very fast. | 我以为那台电脑速度非常快。 I think that computer is very fast. |

| 6 | 公众号更新了。 The public account (on WeChat) has been updated. | 我以为公众号更新了。 I think the public account (on WeChat) has been updated. | 这个动作非常难。 This movement is very difficult. | 我以为这个动作非常难。 I think this movement is very difficult. |

| 7 | 走廊灯坏了。 The corridor light is broken. | 我推测走廊灯坏了。 I infer the corridor light is broken. | 那个地方很冷。 That place is very cold. | 我推测那个地方很冷。 I infer that place is very cold. |

| 8 | 牛奶过期了。 The milk has expired. | 我推测牛奶过期了。 I infer the milk has expired. | 那个发型很好看。 That hairstyle looks very great. | 我推测那个发型很好看。 I infer that hairstyle looks very great. |

| 9 | 火车晚点了。 The train is late. | 我推测火车晚点了。 I infer the train is late. | 那个门非常坚固。 That door is very sturdy. | 我推测那个门非常坚固。 I infer that door is very sturdy. |

| 10 | 房门钥匙丢了。 The key is missing. | 我估计房门钥匙丢了。 I reckon the key is missing. | 那个游戏很好玩。 That game is very fun. | 我估计那个游戏很好玩。 I reckon that game is very fun. |

| 11 | 卧室门开了。 The bedroom’s door is open. | 我估计卧室门开了。 I reckon the bedroom’s door is open. | 这个瓶子很值钱。 This bottle is very valuable. | 我估计这个瓶子很值钱。 I reckon this bottle is very valuable. |

| 12 | 李飞毕业了。 Li Fei has graduated. | 我估计李飞毕业了。 I reckon Li Fei has graduated. | 这个菜很好吃。 This dish is very delicious. | 我估计这个菜很好吃。 I reckon this dish is very delicious. |

| 13 | 中国队赢了。 The Chinese team won. | 我猜(测)中国队赢了。 I guess the Chinese team won. | 那件衬衫很干净。 That shirt is very clean. | 我猜(测)那件衬衫很干净。 I guess that shirt is very clean. |

| 14 | 桥面结冰了。 The bridge has frozen over. | 我猜(测)桥面结冰了。 I guess the bridge has frozen over. | 这本书非常难。 This book is very difficult. | 我猜(测)这本书非常难。 I guess this book is very difficult. |

| 15 | 会议结束了。 The meeting has ended. | 我猜(测)会议结束了。 I guess the meeting has ended. | 那个菜非常辣。 That dish is very spicy. | 我猜(测)那个菜非常辣。 I guess that dish is very spicy. |

| 16 | 外面起风了。 It starts to be windy outside. | 我推断外面起风了。 I infer it starts to be windy outside. | 那辆车很便宜。 That car is very cheap. | 我推断那辆车很便宜。 I infer that car is very cheap. |

| 17 | 小区停电了。 There is a power outage in the community. | 我推断小区停电了。 I infer there is a power outage in the community. | 这个时间非常适合。 This time is very suitable. | 我推断这个时间非常适合。 I infer this time is very suitable. |

| 18 | 汽油涨价了。 The gasoline prices have gone up. | 我推断汽油涨价了。 I infer gasoline prices have gone up. | 这个人非常有趣。 This person is very interesting. | 我推断这个人非常有趣。 I infer this person is very interesting. |

References

- Aikhenvald, A. Y. (2004). Evidentiality. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M., & Sundberg, R. (2021). Subjectivity (Re)visited: A corpus study of English forward causal connectives in different domains of spoken and written language. Discourse Processes, 58(3), 260–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S. (2020). When the owner of information is unsure: Epistemic uncertainty influences evidentiality processing in Turkish. Lingua, 247, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S. A., Griffiths, T. L., & Hawkins, R. D. (2022). A pragmatic account of the weak evidence effect. Open Mind, 6(28), 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, J., & Pagliuca, W. (1985). Cross-linguistic comparison and the development of grammatical meaning. In J. Fisiak (Ed.), Historical Semantics, historical word formation (pp. 59–83). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, W. (1986). Evidentiality in English conversation and academic writing. In W. Chafe, & J. Nichols (Eds.), Evidentiality: The linguistic coding of epistemology (pp. 261–272). Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Cornillie, B. (2009). Evidentiality and epistemic modality: On the close relationship of two different categories. Functions of Language, 16(1), 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, J., Trotzke, A., Scontras, G., Wittenberg, E., & Goodman, N. D. (2019). Definitely, maybe: A new experimental paradigm for investigating the pragmatics of evidential devices across languages. Journal of Pragmatics, 140, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, F. (1999). Evidentiality and epistemic modality: Setting boundaries. Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 18(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H. (2015). The evaluative analysis of evidentiality in Chinese. Foreign Language Research, 38(05), 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, J. W. (2007). The stance triangle. In R. Englebretwson (Ed.), Stancetaking in discourse: Participantivity, evaluation, interaction (pp. 139–182). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Faller, M. T. (2002). Semantics and pragmatics of evidentials in Cuzco Quechua [Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University]. [Google Scholar]

- Faller, M. T. (2006). Evidentiality and epistemic modality at the semantics/pragmatics interface. In Workshop on philosophy & linguistics. Citeseer. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H. M. (2006). A review of studies on evidentiality. Modern Foreign Languages, 29(02), 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fernbach, P. M., Darlow, A., & Sloman, S. A. (2011). When good evidence goes bad: The weak evidence effect in judgment and decision-making. Cognition, 119, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, A., & Degen, J. (2023). Evidential uncertainty involves both pragmatic and extralinguistic reasoning: A computational account. In M. Goldwater, F. K. Anggoro, B. K. Hayes, & D. C. Ong (Eds.), Proceedings of the 45th annual conference of the cognitive science society (Vol. 45, pp. 95–101). eScholarship. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, J. H., & Yu, G. W. (2024). A study of the usage of the hearsay evidential marker Jushuo. Chinese Teaching in the World, 38(4), 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M., Roseano, P., Borràs-Comes, J., & Prieto, P. (2017). Epistemic and evidential marking in discourse: Effects of register and debatability. Lingua, 186–187(1), 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravano, A., Benus, S., Hirschberg, J., German, E. S., & Ward, G. (2009). The effect of contour type and epistemic modality on the assessment of speaker certainty. Speech Prosody. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, Y., Orita, N., Ying, D., Koshizuka, T., & Sakai, H. (2020). A neurolinguistic investigation into semantic differences of evidentiality and modality. In M. Franke, N. Kompa, M. Y. Liu, J. L. Mueller, & J. Schwab (Eds.), Proceedings of sinn und bedeutung (Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 273–290). Osnabrück University. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, R. W. (1990). Subjectification. Cognitive Linguistics, 1, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, R. W. (2008). Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., & Kaiser, E. (2021). Consequences of evidential marking on the interpretation of subjective predicates: Experimental data from Korean. In P. G. Grosz, L. Martí, H. Pearson, Y. Sudo, & S. Zobel (Eds.), Proceedings of sinn und bedeutung (Vol. 25, pp. 545–562). University College London and Queen Mary University of London. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R. V. (2024). emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.10.0. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Li, S. (2016). Comparative study on the epistemic stance marker “wǒ rèn wéi” and “wǒ jué de”—Based on modern Chinese language corpus. Journal of Shenyang Institute of Engineering (Social Science), 12(1), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martire, K. A., Kemp, R. I., Watkins, I., Sayle, M. A., & Newell, B. R. (2013). The expression and interpretation of uncertain forensic science evidence: Verbal equivalence, evidence strength, and the weak evidence effect. Law and Human Behavior, 37(3), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T., Yamamoto, T., Miura, Y., & Mccagg, P. (2016). Young children’s early sensitivity to linguistic indications of speaker certainty in their selective word learning. Lingua, 175–176, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuyts, J. (2012). Notions of (inter)subjectivity. English Text Construction, 5(1), 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, F. R. (1986). Mood and modality. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pillow, B. H. (2002). Children’s and adults’ evaluation of the certainty of deductive inferences, inductive inferences, and guesses. Child Development, 73(3), 779–792. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3696250 (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Plungian, V. (2001). The place of evidentiality within the universal grammatical space. Journal of Pragmatics, 33, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R (Version 4.3.3) [Computer software]. R Core Team. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, T., & Spooren, W. (2015). Causality and subjectivity in discourse: The meaning and use of causal connectives in spontaneous conversation, chat interactions and written text. Linguistics, 53(1), 53–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, A. (2021). Evidentiality in abductive reasoning: Experimental support for a modal analysis of evidentials. Journal of Semantics, 38, 531–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigen, K. H., & Juanchich, M. (2024). Do claims about certainty make estimates less certainty. Cognition, 252, 105911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, S., & Vaid, J. (2018). Activation of source and stance in interpreting evidential and modal expressions in Turkish and English. Dialogue & Discourse, 9(1), 128–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, E. C. (1995). Subjectification in grammaticalisation. In S. Dieter, & W. Susan (Eds.), Subjectivity and subjectivisation: Linguistic perspectives (pp. 31–54). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, E. C. (2010). Revisiting subjectification and intersubjectification. In K. Davidse, L. Vandelanotte, & H. Cuyckens (Eds.), Subjectification, intersubjectification and grammaticalization (pp. 29–70). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, T. (1988). A cross-linguistic survey of the grammaticalization of evidentiality. Studies in Language, 12(1), 51–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H., Li, F., Sanders, T., & Spooren, W. (2021). How subjective are Mandarin reason connectives? Language and Linguistics, 22(1), 166–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G. C. (2014). A research on “Yiwei” and “Renwei”. Chinese Language Learning, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W., & Lyu, S. Q. (2022). Speech act matters: Commitment to what’s said or what’s implicated differs in the case of assertion and promise. Journal of Pragmatics, 191, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y. (2014). A description of the evidentiality system in modern Chinese. Linguistic Research, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. S. (2006). Evidential studies in modern Chinese. Modern Foreign Languages, 4, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Q.; Li, Y. Perceiving Speaker’s Certainty: The Interaction Among Subjectivity of Statement, Evidential Markers, and Evidence Strength. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 912. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070912

Fang Q, Li Y. Perceiving Speaker’s Certainty: The Interaction Among Subjectivity of Statement, Evidential Markers, and Evidence Strength. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):912. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070912

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Qiang, and Yinmei Li. 2025. "Perceiving Speaker’s Certainty: The Interaction Among Subjectivity of Statement, Evidential Markers, and Evidence Strength" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 912. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070912

APA StyleFang, Q., & Li, Y. (2025). Perceiving Speaker’s Certainty: The Interaction Among Subjectivity of Statement, Evidential Markers, and Evidence Strength. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 912. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070912