1. Introduction

Cognitive conflict refers to the interference of task-irrelevant information with task-relevant information, typically arising when individuals are required to make decisions among competing options or information representations during the course of information processing (

Braver, 2001;

Melcher & Gruber, 2009). Empirical evidence suggests that encountering cognitive conflict activates the cognitive control system (

Miller & Cohen, 2001), leading to dynamic adjustments in information processing that culminate in the emergence of conflict adaptation. Conflict adaptation is characterized by improved processing efficiency following the experience of cognitive conflict, thereby showing better control and processing abilities in subsequent similar tasks (

Gratton et al., 1992). However, existing research on conflict adaptation has predominantly concentrated on performance within classic cognitive control paradigms, such as the Flanker task (e.g.,

J. W. Brown et al., 2007;

Gratton et al., 1992;

Ullsperger et al., 2005;

Verbruggen et al., 2006) or the Stroop task (e.g.,

Kerns et al., 2004;

D. Tang et al., 2013;

Tzelgov et al., 1992). Whether conflict adaptation can extend across task boundaries—particularly from general cognitive control tasks (e.g., the Stroop task) to conflict resolution in reading comprehension—remains an open question warranting further empirical investigation. Accordingly, the present study is designed to address two primary objectives: first, to determine whether conflict adaptation effects can generalize across distinct task domains; and second, to explore the role of cognitive control mechanisms in reading comprehension. Through this dual focus, the current study aims to offer novel empirical insights into the cross-domain interplay between cognitive control and language processing.

Evidence supporting the conflict adaptation effect has largely been derived from color-word Stroop paradigms that elicit conflict through systematic manipulation of stimulus congruency. A prototypical example is the classical color-word Stroop task employed by

Kerns et al. (

2004), which required participants to respond to the ink color of color words. This paradigm included two conditions: a congruent condition (e.g., the word “red” printed in red ink) and an incongruent condition (e.g., the word “red” printed in green ink). The study demonstrated that activation intensity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) during incongruent trials significantly predicted subsequent changes in both neural activity and behavioral adjustments in subsequent conflict trials. Behaviorally, participants exhibited significantly reduced reaction times in subsequent incongruent trials, with performance in some instances approaching that observed under congruent conditions (

Kerns et al., 2004;

Schmidt & Cheesman, 2005). In the context of classical color-word Stroop tasks, neural activation patterns exhibit systematic modulation as individuals engage in sustained conflict processing. Specifically, the activation intensity of the ACC in response to conflict tends to decrease across consecutive conflict trials, whereas the involvement of frontal lobe regions increases, reflecting a functional redistribution of cognitive control resources (

Egner & Hirsch, 2005). This dynamic reconfiguration of neural activity indicates that the individual’s cognitive processing has adapted over time, a phenomenon commonly referred to as the conflict adaptation effect. Drawing on the activation patterns and predictive role of the ACC, researchers have proposed that conflict adaptation arises from enhanced cognitive control triggered by conflict in a preceding trial, thereby facilitating more efficient processing of subsequent conflict-related information.

Building on this foundation, researchers have further extended the scope of conflict adaptation. In the classical color-word Stroop paradigm, conflict arises from the discrepancy between ink color and word meaning. However, to explore whether more complex color-word Stroop tasks can similarly elicit conflict adaptation, some researchers have modified the experimental design to include response-level conflicts, such as conflicting keypress actions. For instance,

Liu et al. (

2012) employed a 2:1 mapping paradigm in which participants were instructed to categorize the ink color of color words. Specifically, participants pressed the “Z” key for red or yellow ink and the “M” key for blue or green ink. In the congruent condition, the word meaning and ink color matched (e.g., the word “red” printed in red ink), whereas in the incongruent condition, the word meaning and ink color were associated with opposing response keys (e.g., the word “red” printed in blue ink). By introducing complex color-word Stroop tasks,

Liu et al. (

2012) also observed a robust conflict adaptation effect: conflict trials preceded by a conflict trial elicited significantly faster reaction times compared to those following congruent trials. These findings indicate that, within the Stroop paradigm, both classical color-word Stroop tasks (

Kerns et al., 2004) and complex color-word Stroop tasks (

Liu et al., 2012) can reliably induce conflict adaptation effects.

Furthermore, classical and complex color-word Stroop tasks appear to engage distinct neural circuits, offering a novel perspective on the mechanisms underlying conflict adaptation. For instance,

van Veen and Carter (

2005) integrated functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with a Stroop paradigm to systematically delineate the distinct neural representations associated with these two conflict types. Their findings indicated that classical color-word Stroop tasks primarily recruit the left DLPFC and parietal cortex; however, when task complexity is increased, activation extends to the ACC and the right prefrontal cortex. Notably, the ACC exhibited significantly heightened activation following high-complexity trials, underscoring its central role in conflict detection and subsequent cognitive control processes. More critically,

van Veen and Carter (

2005) proposed that conflicts of varying complexity correspond to distinct stages within the information processing. Classical color-word Stroop tasks are associated with early stages of stimulus recognition and semantic analysis, while color-word Stroop tasks that incorporate response conflict are primarily engaged during later stages involving response selection and execution. This spatial structure and functional attributes dissociation illustrates the cognitive system’s capacity for rapid detection and flexible regulation of conflict through specialized and differentiated neural mechanisms.

It is worth noting that, regardless of whether classical and complex color-word Stroop tasks are employed, prior research has predominantly examined conflict adaptation effects within the same task context (

Mayr & Awh, 2009;

Braem et al., 2014). Whether there will be cross-task conflict adaptation between different tasks remains an open question. In a pioneering study,

Kan et al. (

2013) explored this issue by integrating temporarily ambiguous sentences (e.g., The basketball player accepted the contract that would have to be negotiated) with a Stroop task to examine potential cross-task cognitive control adjustments. The sentence comprehension task was administered using a self-paced reading paradigm, while the Stroop task involved a classical color-word Stroop task. Their findings indicated that the detection of conflict within ambiguous sentences automatically engaged cognitive control mechanisms, thereby facilitating the processing of subsequent incongruent Stroop trials—an effect interpreted as evidence of cross-task conflict adaptation. However, no conflict adaptation effect was observed in the reverse direction: following conflict Stroop trials, reaction times for processing ambiguous and unambiguous sentences did not differ significantly. Nevertheless, using a similar experimental design,

Aczel et al. (

2021) failed to replicate the cross-task conflict adaptation effects reported by

Kan et al. (

2013).

These mixed findings highlight the importance of considering the dynamic nature of cognitive control. Recent studies have indicated that cognitive control is not a static system but one that adjusts flexibly in response to varying task demands and contextual cues (

Gratton et al., 2018). In particular, the dual mechanisms of control (DMC) framework proposes that cognitive control operates via both proactive and reactive modes, which may differ in their susceptibility to cross-task transfer depending on timing, task structure, and motivational context (

Braver, 2012;

Gonthier et al., 2016). These theoretical advances suggest that successful cross-task adaptation may depend on whether control states are sustained across tasks or must be reconfigured, which could explain the inconsistent replication of such effects. More recent research has further refined our understanding of cross-task transfer by emphasizing the role of task similarity or cognitive overlap. For instance,

Ileri-Tayar et al. (

2022) demonstrated that transfer of control settings is more likely when tasks share common control demands or structural features, even if the stimuli differ. Moreover,

H. Tang et al. (

2022) provided neurophysiological evidence that cross-task transfer is modulated by the degree of shared neural control architecture, particularly within prefrontal networks. Collectively, these findings indicate that the success of cross-task adaptation may depend on the degree to which prior control states are applicable to novel tasks.

Given that the Stroop task employed by

Kan et al. (

2013) involved only the classical color-word Stroop task and did not incorporate response conflict,

Dudschig (

2022) extended this line of research by independently manipulating both the classical color-word Stroop task and response conflict tasks to further examine their interaction with the processing of ambiguous sentences. However,

Dudschig (

2022) also failed to replicate the findings of

Kan et al. (

2013). Specifically, no significant differences in reaction times were observed between ambiguous and unambiguous sentences following either type of Stroop conflict, nor was there evidence of a reverse transfer effect. Although some researchers have argued that response conflict evokes greater cognitive control demands than the classical color-word Stroop task (

Milham et al., 2001;

West et al., 2005), no conflict adaptation effects were observed. These findings collectively suggest that the existence of cross-task conflict adaptation between Stroop-based cognitive control tasks and sentence comprehension remains contentious and warrants further empirical clarification.

However, some researchers have argued that these studies predominantly rely on behavioral experimental methods and that behavioral measures typically capture only end-point outcomes of task performance rather than providing insights into the underlying cognitive processes (

Braver, 2012;

Hsu & Novick, 2016;

Posner & Rothbart, 2007). As a result, despite variations across studies, such approaches offer limited explanatory power with respect to the dynamic nature of cognitive adjustment (

Braver, 2012;

Hsu & Novick, 2016;

Just & Carpenter, 1980;

Verguts & Notebaert, 2008). In response to these limitations, recent research has increasingly incorporated eye-tracking technology to obtain continuous time-series data (

Rayner, 1998), thereby enabling the investigation of individuals’ attention allocation patterns and processing strategies during conflict-related tasks. For instance,

Hsu and Novick (

2016) employed a cross-task adaptation paradigm that combined a Stroop task with an auditory verbal comprehension task and used eye-tracking techniques to systematically examine the temporal unfolding of conflict adaptation and its influence on language comprehension. Their findings indicated that, following incongruent Stroop trials, participants were able to more rapidly select and fixate on the image corresponding to the sentence meaning in the subsequent auditory comprehension task, thereby reducing fixation errors and enhancing overall processing efficiency.

Extending previous investigations into cross-task cognitive control,

Hsu et al. (

2021) conducted an eye-tracking study utilizing the Flanker task and demonstrated that the efficiency of cognitive processing during subsequent ambiguous sentence comprehension was significantly enhanced following a conflict trial. Specifically, when participants encountered a high-conflict Flanker trial prior to hearing an ambiguous sentence such as “Put the horse on the binder onto the scarf”, they exhibited shorter response latencies and higher accuracy in selecting the corresponding target image, indicating a heightened capacity for real-time cognitive control during syntactic parsing. Based on the results of these studies, the authors interpreted the findings within the framework of conflict monitoring theory. According to this theory, the cognitive system contains a specialized mechanism that continuously monitors for conflict during information processing. When conflict is detected, particularly in cases where anticipated input diverges from the actual information being processed, the monitoring mechanism becomes engaged and initiates regulatory processes through the allocation of cognitive control resources. The presence of conflict is thus construed as a critical signal indicating increased demands on cognitive control, which prompts the system to mobilize additional resources in order to enhance the efficiency of subsequent cognitive operations (

Botvinick et al., 2001). Within the domain of verbal comprehension, as linguistic input unfolds incrementally, individuals are able to recruit this domain-general cognitive control mechanism to implement real-time adjustments in sentence interpretation, thereby facilitating the resolution of ambiguity and promoting more effective language understanding.

In line with this research trajectory, several scholars have extended the investigation of sentence ambiguity into the domain of thematic role assignment (

Thothathiri et al., 2018). Thematic role assignment refers to the cognitive process through which, during sentence comprehension, the predicate verb is systematically mapped onto its corresponding noun phrases, thereby allowing for the attribution of specific semantic roles such as agent and patient and indicating the functions and relationships of the noun phrases in the action or event (

Dowty, 1991). For instance, in interpreting a sentence such as “The boy ate the apple”, readers must efficiently identify “the boy” as the agent performing the action and “the apple” as the patient receiving it. However, in cases of incongruent sentences, such as “The apple ate the boy”, the thematic roles are assigned in a manner that conflicts with real-world knowledge, creating a strong semantic anomaly. This conflict arises not merely from syntactic structure but from the fundamental mismatch between the expected thematic roles and the actual content of the sentence. Critically, the identification of such conflicts in incongruent sentences typically occurs when encountering the verb and its subsequent object, where the expected agent-patient relationship sharply diverges from common world knowledge. For example, in the sentence “The apple ate the boy”, the conflict is immediately triggered upon encountering the verb “ate” and continues through the processing of the object “the boy” because it violates the basic semantic expectation that an apple cannot act as the agent of eating.

Resolving such conflicts requires substantial cognitive control, as the reader must override the automatic expectation based on prior world knowledge to arrive at a coherent interpretation. This aligns with the conflict monitoring theory, which posits that cognitive control mechanisms are recruited to detect and resolve conflicts when the expected cognitive schema is violated (

Botvinick et al., 2001;

Egner, 2007). In the context of incongruent sentences, the comprehension system is challenged by a mismatch between syntactic structure and real-world semantic expectations. This discrepancy activates conflict monitoring mechanisms that serve to detect and resolve interpretive inconsistencies. Specifically, when the thematic role assignment violates animacy-based plausibility—such as assigning an agent role to an inanimate noun—readers must override the default heuristic that animates are typically agents and inanimates are patients (

Ferreira, 2003;

McRae et al., 1998). Conflict monitoring theory posits that such violations are registered as cognitive conflicts, which trigger increased cognitive control demands to suppress contextually inappropriate interpretations and update the mental representation accordingly (

Botvinick et al., 2001;

Novick et al., 2005). This process is not limited to resolving syntactic ambiguity but extends to thematic processing, wherein the parser actively monitors for semantic implausibility during role assignment. When the initial parse leads to an implausible thematic configuration—as in an inanimate subject performing an action—the system initiates reanalysis mechanisms, reallocating cognitive resources to integrate syntactic and semantic information in a coherent manner (

Kolk & Chwilla, 2007;

van de Meerendonk et al., 2009). In this view, conflict monitoring offers a functional framework for understanding how readers dynamically revise their interpretations in response to implausibility at the level of thematic role assignment. Thus, incongruent sentences elicit conflict signals that engage the broader cognitive control system, particularly in the face of violations that compromise the integration of syntactic form with semantic expectation (

Sturt, 2007).

Thothathiri et al. (

2018) investigated the processing of passive sentences involving thematic role assignment conflicts, such as “The fox was chased by the rabbit”, in which the semantic plausibility favors an interpretation aligned with “The fox chases the rabbit”, whereas the syntactic structure indicates the reverse assignment of roles. The study revealed that when participants were exposed to cognitive conflict in a preceding trial, such as incongruent Stroop stimuli, their performance in subsequent thematic role assignment improved. This facilitation was evidenced by faster and more accurate selection of the picture corresponding to the correct interpretation of the sentence. The observed divergence in gaze trajectories during the processing of conflict sentences indicates that the activation of cognitive control mechanisms facilitates the parsing of thematic role assignments and mitigates errors resulting from semantic interference. These results offer additional empirical support for the conflict monitoring theory by highlighting the modulatory role of cognitive control in resolving syntactic-semantic competition.

Although studies employing eye-tracking methodologies have produced relatively consistent findings, they have predominantly been conducted within the domain of auditory language comprehension. Listening comprehension is an innate human capacity that begins to develop in infancy and follows a biologically driven trajectory (

Pinker, 2000). In contrast, reading comprehension is a learned skill that develops more gradually during childhood and requires explicit instruction and sustained practice. Furthermore, a subset of individuals, such as those with developmental dyslexia, experience persistent difficulties in achieving reading fluency and accuracy. Given these developmental and cognitive differences between listening and reading, the question of whether conflict adaptation occurs in reading comprehension remains unresolved. Existing evidence from self-paced reading paradigms has yielded inconclusive results regarding the presence and reliability of such effects (

Aczel et al., 2021;

Dudschig, 2022;

Kan et al., 2013).

Consequently, it is essential to employ alternative methodologies such as eye-tracking in order to capture dynamic and fine-grained indicators of cognitive processing. Eye-tracking techniques offer higher temporal resolution, which makes them particularly well-suited for investigating the time course of conflict adaptation in language comprehension. Importantly, eye-tracking may also help address concerns regarding the non-replicability of cross-task conflict adaptation effects observed in self-paced reading paradigms (

Dudschig, 2022;

Kan et al., 2013). This is because eye-tracking provides continuous, character-level measures of processing—such as fixation durations and regressions—that are sensitive to subtle variations in cognitive control engagement. In contrast to self-paced reading, which yields only one data point per word or region, eye-tracking captures the real-time dynamics of sentence processing, allowing for more reliable detection of conflict-related effects. Thus, eye-tracking offers a methodological advantage by allowing researchers to pinpoint both the temporal onset and spatial locus of adaptation within the sentence processing stream. This approach may facilitate a more precise examination of the underlying mechanisms and temporal dynamics of conflict adaptation during reading comprehension.

In addition to these methodological considerations, it is important to note that most existing research on conflict adaptation in the reading domain has focused exclusively on the classical color-word Stroop task, with relatively little attention given to the impact of task complexity on conflict adaptation. However, it is well established that Stroop tasks of varying complexity are associated with distinct neural activation patterns, suggesting that task complexity may significantly influence the underlying cognitive control processes involved (

van Veen & Carter, 2005). Investigating the differential effects of various types of conflict on sentence comprehension can facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms and dynamic processes of conflict adaptation in language processing.

Moreover, cognitive control plays a critical role in both syntactic parsing and semantic integration during reading comprehension, particularly when individuals are confronted with conflicting cues from multiple information sources (

Novick et al., 2005). In this context, the Chinese language presents unique processing demands. As a zero-morphology language, Chinese lacks explicit morphological markers and clear word boundaries that are typically present in alphabetic writing systems (

Wadley et al., 1987). In addition, the ideographic nature of Chinese characters provides dense visual information at the perceptual level, thereby increasing the cognitive load during reading. These linguistic and orthographic characteristics necessitate that Chinese readers engage more sophisticated and flexible cognitive control mechanisms, particularly when processing syntactic structures involving thematic role assignment. For example, certain Chinese verbs may simultaneously function as predicates and as complements within an embedded clause. Accurate role assignment in such cases depends heavily on contextual interpretation, requiring readers to dynamically monitor, revise, and resolve structural ambiguities. This judgment process typically involves both the initial interpretation and subsequent re-evaluation of conflicting information, thereby requiring readers to engage a high level of conflict adaptation in order to adjust their interpretive strategies and respond efficiently to contextual changes.

The present study employed two experiments to investigate the influence of conflict adaptation on thematic role assignment in Chinese sentence comprehension. Experiment 1 utilized a classical color-word Stroop task to assess basic conflict adaptation effects, while Experiment 2 introduced a more complex Stroop task by incorporating response-level conflict through a 2:1 response mapping paradigm. This manipulation added an additional conflict at the execution stage, allowing us to distinguish how increased task complexity, particularly involving response conflict, influences subsequent language comprehension. The current design allowed for a more comprehensive examination of the impact of task complexity on cognitive control processes during sentence comprehension.

To investigate the impact of cognitive conflict on sentence comprehension, the present study employed an eye-tracking reading paradigm in which participants were visually presented with sentences containing either congruent or incongruent thematic role assignments. By comparing eye movement patterns following Stroop trials that varied in conflict complexity, the study aimed to determine whether prior exposure to cognitive conflict facilitates the processing of syntactic structures involving thematic role ambiguity. This methodological approach allowed for a fine-grained, temporally sensitive analysis of conflict adaptation as it unfolds during real-time sentence processing. Notably, in contrast to previous studies that have primarily relied on auditory comprehension paradigms, the current research focused on visually presented language information within a naturalistic reading context, thereby broadening the methodological scope of conflict adaptation research in language comprehension.

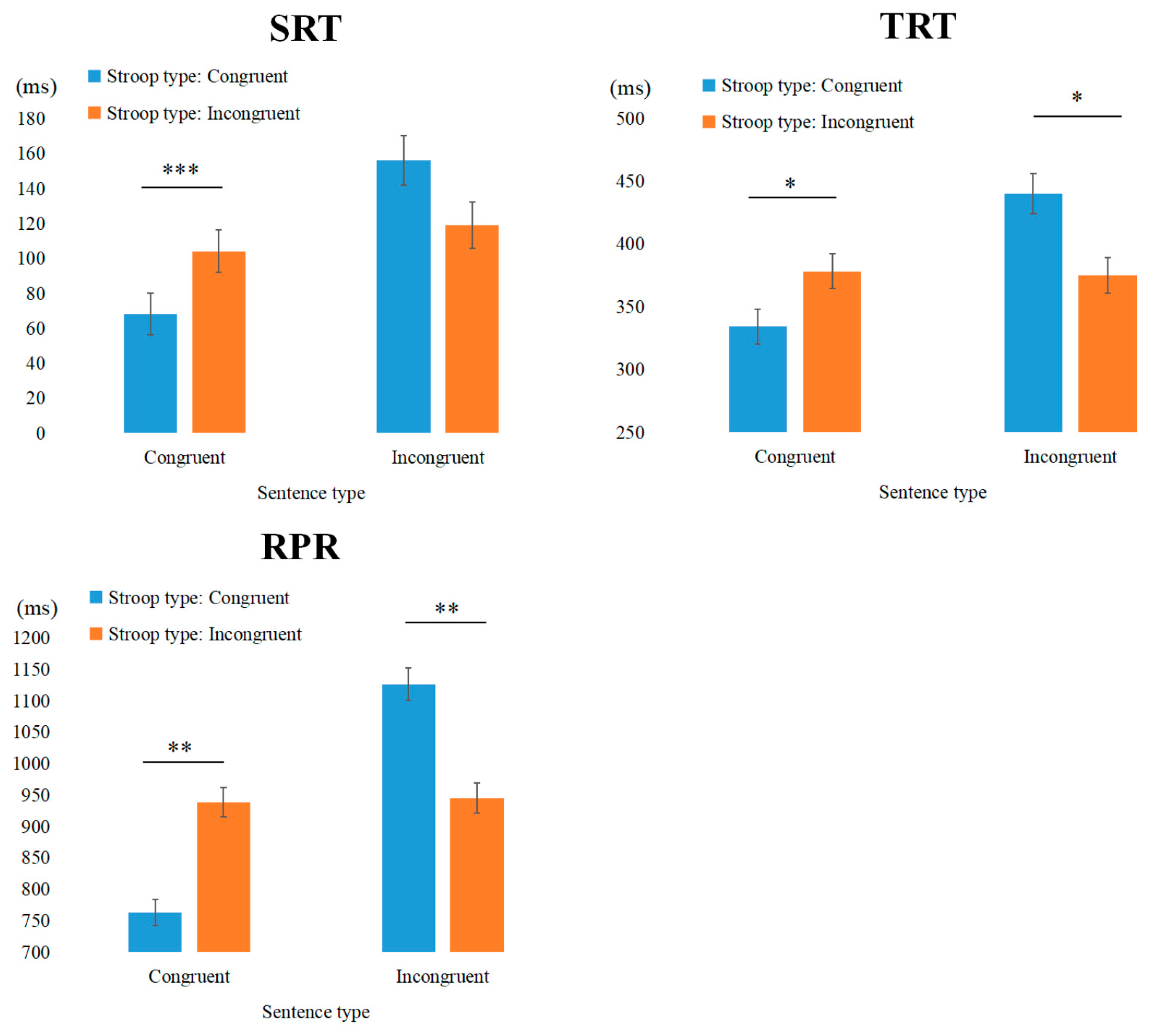

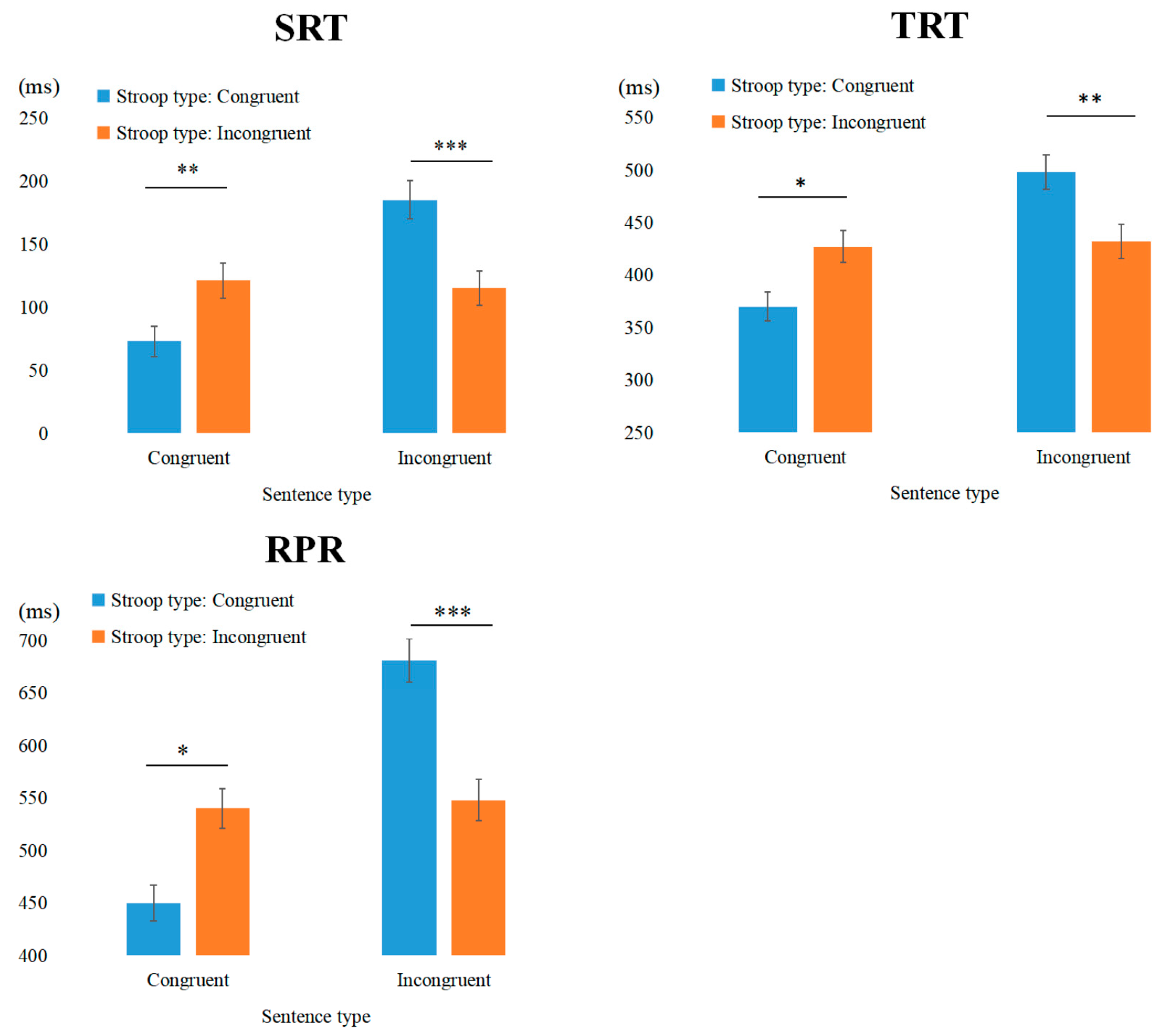

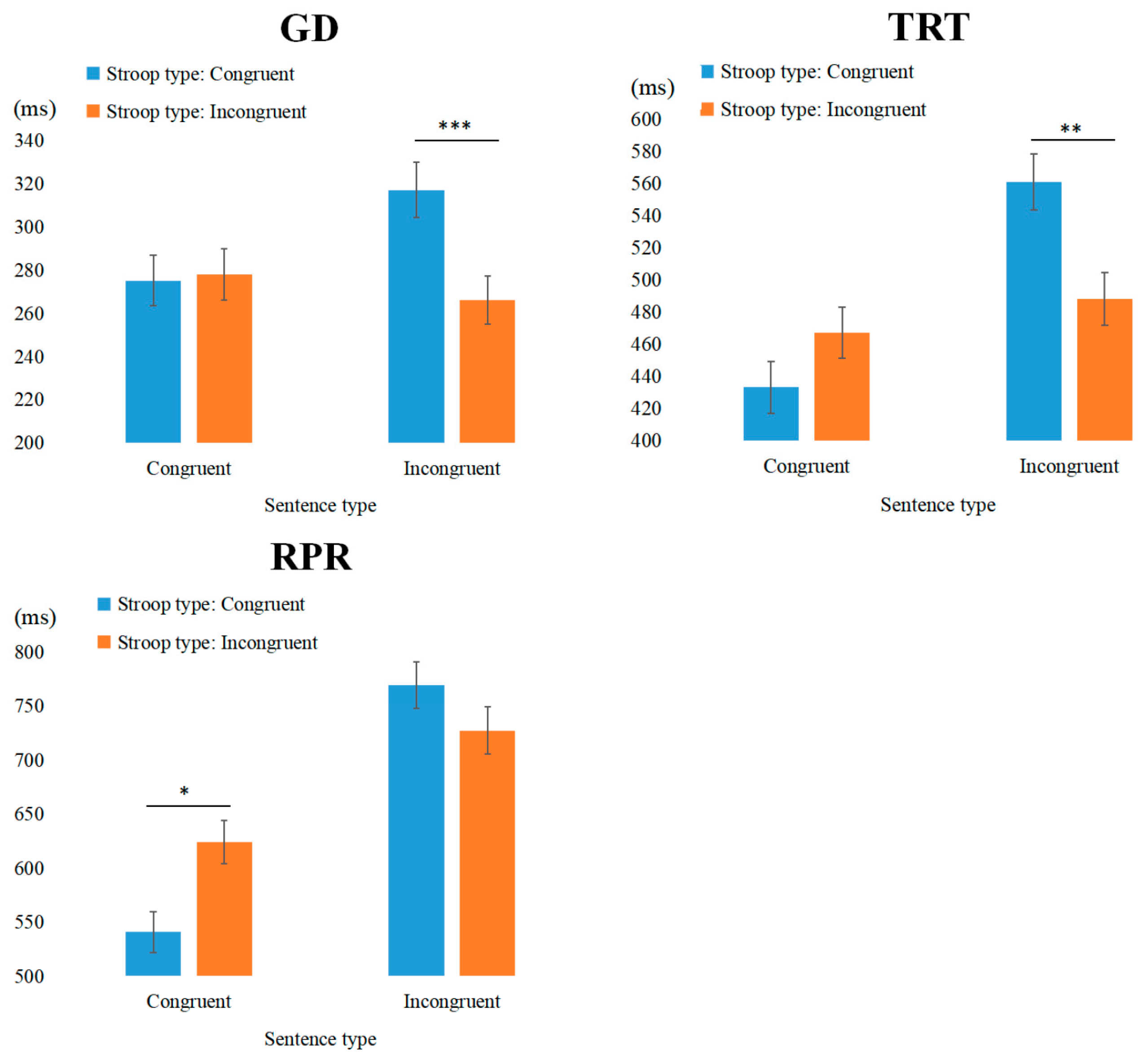

Utilizing eye-tracking methodology, the present study simultaneously examines both early and late stages of sentence processing in order to assess the dynamic impact of conflict adaptation on thematic role assignment. Early-stage processing was indexed by First Fixation Duration (FFD) and Gaze Duration (GD), which primarily reflect lexical access and initial syntactic parsing (

Rayner, 2009). Gaze duration is defined as the sum of all first-pass fixations on a given interest area, from the moment the eyes first land on that region until they move away for the first time. These measures are considered sensitive to early decoding and the detection of incongruent linguistic input (

Connor et al., 2015;

Zargar et al., 2020). Later-stage processing was captured through Second Reading Time (SRT) and Total Reading Time (TRT), which reflect late syntactic integration and higher-level semantic processing. These indicators are commonly interpreted as evidence of syntactic reanalysis and meaning integration, as they index the regulation and repair mechanisms involved in reading comprehension (

Clifton et al., 2007;

Hyönä, 2011). In addition, we also pay attention to the Regression Path Reading time (RPR), which reflects the time spent rereading prior regions of text following comprehension difficulty. This measure is widely considered an indicator of syntactic revision or semantic reinterpretation triggered by conflict detection (

Von der Malsburg & Vasishth, 2011).

Drawing on the findings of

Thothathiri et al. (

2018), the present study hypothesizes that conflict induced by the Stroop task will elicit a cross-task conflict adaptation effect, which in turn modulates the allocation of cognitive control resources during thematic role assignment. Specifically, it is expected that following exposure to conflict, individuals will exhibit enhanced cognitive control, as reflected in fixation durations during the processing of thematic role assignment. In particular, eye movement patterns in the region of interest are anticipated to be influenced by the congruency of the Stroop condition in the preceding trial (

Freitas et al., 2007;

Kim et al., 2010). Moreover, based on the findings of

Clayson and Larson (

2011), conflict adaptation is hypothesized to exert its strongest effects during later stages of cognitive processing, particularly when semantic integration and syntactic decision-making are required (

Botvinick et al., 2001;

Egner, 2007). Therefore, the effect is expected to manifest in late eye movement indicators, such as TRT and RPR, with reduced processing durations observed when a Stroop conflict trial precedes a thematic role conflict sentence (

Gratton et al., 1992;

Ye & Zhou, 2009). Finally, given that color-word Stroop tasks involving response conflicts have been shown to elicit stronger and more sustained activation of the cognitive control network than classical color-word Stroop tasks (

Milham et al., 2001;

West et al., 2005), it is further hypothesized that the conflict adaptation effect will emerge earlier in the time course following complex color-word Stroop tasks. Accordingly, participants are expected to exhibit shorter fixation durations in early-stage indicators after experiencing a complex conflict trial, suggesting more rapid deployment of control resources to facilitate syntactic parsing and reduce interference from semantic incongruity (

Notebaert & Verguts, 2008).