Adverse Experiences in Early Childhood and Emotional Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Preschoolers: Psychological Resilience and Problematic Media Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ACEs and Emotional Behavioral Problems in Young Children

1.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Resilience

1.3. The Mediating Role of Problematic Media Use

1.4. The Serial Mediation Effect of Psychological Resilience and Problematic Media Use

1.5. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Information

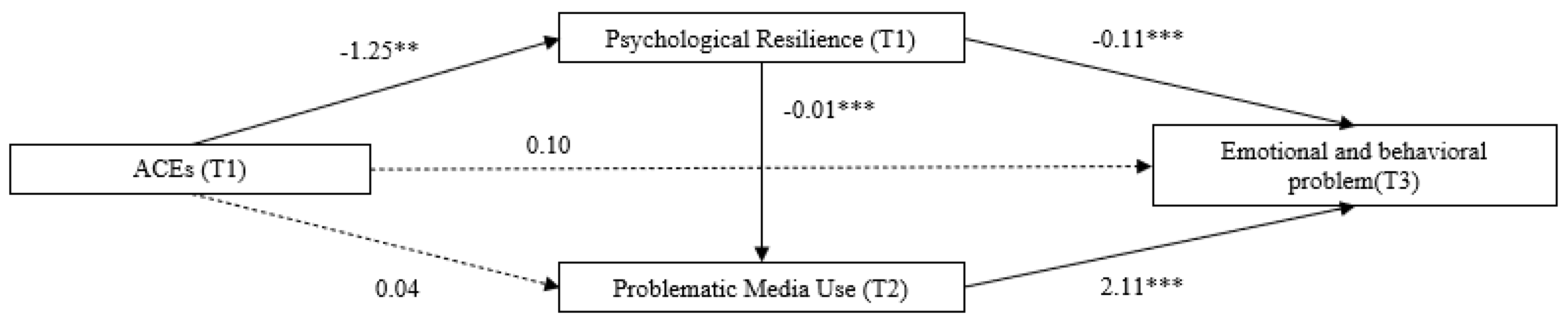

3.2. The Serial Mediating Effects of Psychological Resilience and PMU

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arslan, G. (2016). Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, J. C., & Martinez, C. D. (2006). Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 24(3), 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, S. J., & DeFleur, M. L. (1976). A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communication Research, 3(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, M. A., & Thompson, L. A. (2018). Association of adverse childhood experiences with co-occurring health conditions in early childhood. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 39(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press Google Schola, 2, 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q., An, J., Yang, Y., Peng, P., Xu, S., Xu, X., & Xiang, H. (2022). Correlation among psychological resilience, loneliness, and internet addiction among left-behind children in China: A cross-sectional study. Current Psychology, 41(7), 4566–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J. S., & Voris, D. S. (2018). One-year stability of the Devereux early childhood assessment for preschoolers. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 36(8), 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. K., Wang, D., & Jackson, A. P. (2019). Adverse experiences in early childhood and their longitudinal impact on later behavioral problems of children living in poverty. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104181. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K., & Hong, Y. J. (2025). Differential roles of problematic media use by mothers and toddlers in the relation between parenting stress and toddlers’ socioemotional development. Infant Behavior and Development, 78, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CNNIC. (2023). The 50th statistical report on China’s internet development. Available online: https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2023/0828/c88-10829.html (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Coyne, S. M., Shawcroft, J., Holmgren, H., Christensen-Duerden, C., Ashby, S., Rogers, A., Reschke, P. J., Barr, R., Domoff, S., Van Alfen, M., Meldrum, M., & Porter, C. L. (2024). The growth of problematic media use over early childhood: Associations with long-term social and emotional outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 159, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çaylan, N., Yalçın, S. S., Erat Nergiz, M., Yıldız, D., Oflu, A., Tezol, Ö., Çiçek, Ş., & Foto-Özdemir, D. (2021). Associations between parenting styles and excessive screen usage in preschool children. Turkish Archives of Pediatrics, 56(3), 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X., Liang, M., Song, Q., Su, W., Li, N., Liu, H., Wu, Y., Guo, X., Wang, H., Zhang, J., Qin, Q., Sun, L., Chen, M., & Sun, Y. (2023a). Development of psychological resilience and associations with emotional and behavioral health among preschool left-behind children. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 58(3), 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Ma, S., Liu, H., Wang, H., Li, N., Song, Q., Su, W., Liang, M., Gui, X., Sun, L., Qin, Q., Chen, M., & Sun, Y. (2023b). The relationships between sleep disturbances, resilience and anxiety among preschool children: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 168, 111203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domoff, S. E., Borgen, A. L., & Radesky, J. S. (2020). Interactional theory of childhood problematic media use. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domoff, S. E., Harrison, K., Gearhardt, A. N., Gentile, D. A., Lumeng, J. C., & Miller, A. L. (2019). Development and validation of the problematic media use measure: A parent report measure of screen media “addiction” in children. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, A. (1982). The relative effectiveness of procedures commonly used in multiple regression analysis for dealing with missing values. The American Statistician, 36(4), 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Kou, J., & Coghill, D. (2008). The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in China. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., & Williamson, D. F. (2002). Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: Implications for health and social services. Violence and Victims, 17(1), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S. E., Levitt, P., & Nelson, C. A., III. (2010). How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Development, 81(1), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartland, D., Riggs, E., Muyeen, S., Giallo, R., Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H., Herrman, H., Bulford, E., & Brown, S. J. (2019). What factors are associated with resilient outcomes in children exposed to social adversity? A systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(4), e024870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A. L., Faulkner, B., & Wekerle, C. (2013). The relationship among internal resilience, smoking, alcohol use, and depression symptoms in emerging adults transitioning out of child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z., Jin, L., Huang, J., Akram, H. R., & Cui, Q. (2023). Resilience and problematic smartphone use: A moderated mediation model. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H., Stewart, D. E., Diaz-Granados, N., Berger, E. L., Jackson, B., & Yuen, T. (2011). What is resilience? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Fuentes, S., Martí-Vilar, M., & Ruiz-Ordoñez, Y. (2023). Problematic internet use and resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing Reports, 13(1), 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, M. R., Yoon, S., Voith, L. A., Kobulsky, J. M., & Steigerwald, S. (2015). Resilience in physically abused children: Protective factors for aggression. Behavioral Sciences, 5(2), 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J., Yu, L., Ting, S. M. R., Sze, Y. T., & Fang, X. (2011). The status and characteristics of couple violence in China. Journal of Family Violence, 26(2), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X. L., Wang, H. Z., Guo, C., Gaskin, J., Rost, D. H., & Wang, J. L. (2017). Psychological resilience can help combat the effect of stress on problematic social networking site usage. Personality and Individual Differences, 109, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. C., Chen, Y., Cheung, S., Greene, L., & Lu, S. (2019). Resilience, emotional problems, and behavioural problems of adolescents in China: Roles of mindfulness and life skills. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1158–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., Li, X., Zhao, J., & An, Y. (2023). Relations among resilience, emotion regulation strategies and academic self-concept among Chinese migrant children. Current Psychology, 42(10), 8019–8027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z., Griffiths, M. D., & Sheffield, D. (2017). An investigation into problematic smartphone use: The role of narcissism, anxiety, and personality factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M. E., Wade, R., Lin, Y., Morrow, L. M., & Reichman, N. E. (2016). Adverse experiences in early childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics, 137(2), e20151839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. (2013). The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 64(5), 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerker, B. D., Zhang, J., Nadeem, E., Stein, R. E., Hurlburt, M. S., Heneghan, A., Landsverk, J., & Horwitz, S. M. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and mental health, chronic medical conditions, and development in young children. Academic Pediatrics, 15(5), 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J. E., Chang, L., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Oburu, P., Palmérus, K., Bacchini, D., Pastorelli, C., Bombi, A. S., Zelli, A., Tapanya, S., Chaudhary, N., Deater-Deckard, K., Manke, B., & Quinn, N. (2005). Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development, 76(6), 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBuffe, P. A., & Naglieri, J. A. (2012). Devereux early childhood assessment for preschoolers: User’s guide and technical manual. Kaplan Early Learning Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Wang, J., Xiao, B., Li, Y., & Li, H. (2024). Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the problematic media use measure. Early Education and Development, 35(1), 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A. F., Chu, A., Van Horn, P., & Harris, W. W. (2011). Trauma in early childhood: Empirical evidence and clinical implications. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liming, K. W., & Grube, W. A. (2018). Wellbeing outcomes for children exposed to multiple adverse experiences in early childhood: A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(4), 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S., Hall, T., Constable, L., Paton, K., Sanci, L., Goldfeld, S., & Hiscock, H. (2022). Screening for adverse childhood experiences in children: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 149(2), e2021051884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, W. W., Ng, I. S., & Wong, C. C. (2011). Resilience: Enhancing well-being through the positive cognitive triad. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganello, J. A., & Taylor, C. A. (2009). Television exposure as a risk factor for aggressive behavior among 3-year-old children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(11), 1037–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Manyema, M., Norris, S. A., & Richter, L. M. (2018). Stress begets stress: The association of adverse childhood experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress. BMC Public Health, 18, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, E. J., & Viding, E. (2015). The theory of latent vulnerability: Reconceptualizing the link between childhood maltreatment and psychiatric disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 27(2), 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, E., Vreeker, A., & Hillegers, M. (2021). Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents: An update of the recent literature and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(6), 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C. A., Chang, Y.-H., Choy, O., Tsai, M.-C., & Hsieh, S. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with reduced psychological resilience in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Children, 9(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurius, P. S., Uehara, E., & Zatzick, D. F. (2013). Intersection of stress, social disadvantage, and life course processes: Reframing trauma and mental health. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 16(2), 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T., Sun, Y., Ye, P., Yan, J., Wang, X., & Song, Z. (2024). The association between family functioning and problem behaviors among Chinese preschool left-behind children: The chain mediating effect of emotion regulation and psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1343908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, V., Gioia, F., & Boursier, V. (2023). Problematic media use among children up to the age of 10: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sage, M., Randolph, K., Fitch, D., & Sage, T. (2021). Internet use and resilience in adolescents: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(2), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A., Passanisi, A., Caretti, V., La Marca, L., Granieri, A., Iacolino, C., Gervasi, A. M., Maganuco, N. R., & Billieux, J. (2017). Traumatic experiences, alexithymia, and Internet addiction symptoms among late adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciaraffa, M. A., Zeanah, P. D., & Zeanah, C. H. (2018). Understanding and promoting resilience in the context of adverse childhood experiences. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, M., Ungar, M., Wedyaswari, M., & Shojaee, M. (2024). The Role of resilience as a mediating factor between adverse childhood experience and mental health in adolescents receiving child welfare services in Nova Scotia. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., Garner, A. S., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., & Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenrath, M. A., Clarke, M. E., & Kutcher, S. (2011). The science of brain and biological development: Implications for mental health research, practice and policy. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(4), 298. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M., Adachi, M., Nishimura, T., Hirota, T., Yasuda, S., Kuribayashi, M., & Nakamura, K. (2018). Prevalence of pathological and maladaptive Internet use and the association with depression and health-related quality of life in Japanese elementary and junior high school-aged children. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Li, M., Geng, J., Wang, H., Nie, J., & Lei, L. (2023). Meaning in life and self-control mediate the potential contribution of harsh parenting to adolescents’ problematic smartphone use: Longitudinal multi-group analyses. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 2159–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, E. M. (2022). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health and development in young children. Global Pediatric Health, 9, 2333794X221078708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsley, J. D., McIntyre, J. C., Bentall, R. P., & Corcoran, R. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and problematic social media use: The role of attachment and depression. Psychiatry Research, 267, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H., Wen, L. M., & Rissel, C. (2015). Associations of parental influences with physical activity and screen time among young children: A systematic review. Journal of Obesity, 2015, 546925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, F. C., Yıldırım, O., & Köksal, B. (2024). The mediating and buffering effect of resilience on the relationship between loneliness and social media addiction among adolescent. Current Psychology, 43(28), 24080–24090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Ng, W. Q., Yang, Y., & Yang, S. (2022). Inconsistent media mediation and problematic smartphone use in preschoolers: Maternal conflict resolution styles as moderators. Children, 9(6), 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N., Qi, Y., Lu, J., Hu, J., & Ren, Y. (2021). Teacher-child relationships, self-concept, resilience, and social withdrawal among Chinese left-behind children: A moderated mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 129, 106182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Huang, L., Mao, J., DNA, G., & Luo, S. (2022). Childhood maltreatment, automatic negative thoughts, and resilience: The protective roles of culture and genes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1–2), 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zetino, Y. L., Galicia, B. E., & Venta, A. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences, resilience, and emotional problems in Latinx immigrant youth. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J., Wu, Y., Qu, G., Wang, L., Wu, W., Tang, X., Liu, H., Chen, X., Zhao, T., Xuan, K., & Sun, Y. (2021). The relationship between psychological resilience and emotion regulation among preschool left-behind children in rural China. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 26(5), 595–606. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q., Chew, P., Oei, A., Chu, C. M., Ong, M., & Hoo, E. (2024). Longitudinal effects of cumulative adverse childhood experiences on internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents in out-of-home care: Emotion dysregulation as a mediator. Adversity and Resilience Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Zhang, G., & Anme, T. (2022). Patterns of adverse childhood experiences among Chinese preschool parents and the intergenerational transmission of risk to offspring behavioural problems: Moderating by coparenting quality. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2137913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y., Zhang, G., & Anme, T. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences, resilience, and emotional problems in young chinese children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y., Zhang, G., & Zhan, S. (2024). Association of parental adverse childhood experiences with offspring sleep problems: The role of psychological distress and harsh discipline. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 18(1), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Category | n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Child’s age at baseline year age (Month) | 33.29 ± 3.97 | |

| Child’s sex | Male | 265 (49.6) |

| Female | 269 (50.4) | |

| Father’s education level | Primary school or below | 1 (0.2) |

| Middle school or below | 39 (7.3) | |

| High school or vocational secondary school degree | 66 (12.4) | |

| Vocational college degree | 133 (24.9) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 234 (43.8) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 61 (11.4) | |

| Mother’s education level | Primary school or below | 3 (0.6) |

| Middle school or below | 33 (6.2) | |

| High school or vocational secondary school degree | 63 (11.8) | |

| Vocational college degree | 150 (28.1) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 237 (44.4) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 48 (9.0) | |

| Annual family income | <50,000 RMB | 19 (3.6) |

| 50,001–100,000 RMB | 79 (14.8) | |

| 100,001–150,000 RMB | 137 (25.7) | |

| 150,001–300,000 RMB | 206 (38.6) | |

| >300,000 RMB | 93 (17.4) | |

| Adverse childhood experiences (T1) | 0.40 ± 0.99 | |

| Psychological resilience (T1) | 44.36 ± 10.00 | |

| Problematic media use (T2) | 1.62 ± 0.60 | |

| Emotional and behavioral problems (T3) | 8.20 ± 4.09 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Adverse childhood experiences (T1) | -- | ||

| 2 Psychological resilience (T1) | −0.131 ** | -- | |

| 3 Problematic media use (T2) | 0.080 | −0.183 ** | -- |

| 4 Emotional and behavioral problems (T3) | 0.085 * | −0.328 ** | 0.365 ** |

| Predictors | Model 1 (Criterion PR) | Model 2 (Criterion PMU) | Model 3 (Criterion EBPs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | T | b | t | b | t | |

| CO: Children’s age | 0.07 | 0.57 | −0.01 | −0.24 | −0.01 | −0.10 |

| CO: Children’s gender | 1.41 | 1.66 | −0.01 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.81 |

| CO: FEL | 0.23 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 0.19 | 0.87 |

| CO: MEL | 0.95 | 1.58 | −0.05 | −1.40 | −0.23 | −1.01 |

| CO: AFI | 0.45 | 1.01 | −0.02 | −0.85 | −0.20 | −1.21 |

| X: ACEs | −1.25 | −2.88 ** | 0.04 | 1.38 | 0.1 | 0.67 |

| ME: PR | −0.01 | −3.83 *** | −0.11 | −6.42 *** | ||

| ME: PMU | 2.11 | 7.79 *** | ||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.21 | |||

| F | 4.03 *** | 3.58 ** | 17.41 *** | |||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||

| ACEs → EBPs | 0.109 | 0.163 | −0.210 | 0.428 |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| ACEs → PR → EBPs | 0.132 | 0.044 | 0.051 | 0.221 |

| ACEs → PMU → EBPs | 0.076 | 0.054 | −0.016 | 0.198 |

| ACEs → PR → PMU → EBPs | 0.026 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, G. Adverse Experiences in Early Childhood and Emotional Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Preschoolers: Psychological Resilience and Problematic Media Use. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070898

Zhu Y, Yang L, Zhang G. Adverse Experiences in Early Childhood and Emotional Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Preschoolers: Psychological Resilience and Problematic Media Use. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070898

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yantong, Liu Yang, and Gengli Zhang. 2025. "Adverse Experiences in Early Childhood and Emotional Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Preschoolers: Psychological Resilience and Problematic Media Use" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070898

APA StyleZhu, Y., Yang, L., & Zhang, G. (2025). Adverse Experiences in Early Childhood and Emotional Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Preschoolers: Psychological Resilience and Problematic Media Use. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 898. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070898