The Impact of Perceived Organizational Politics on Peer Voice Endorsement: A Dual Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

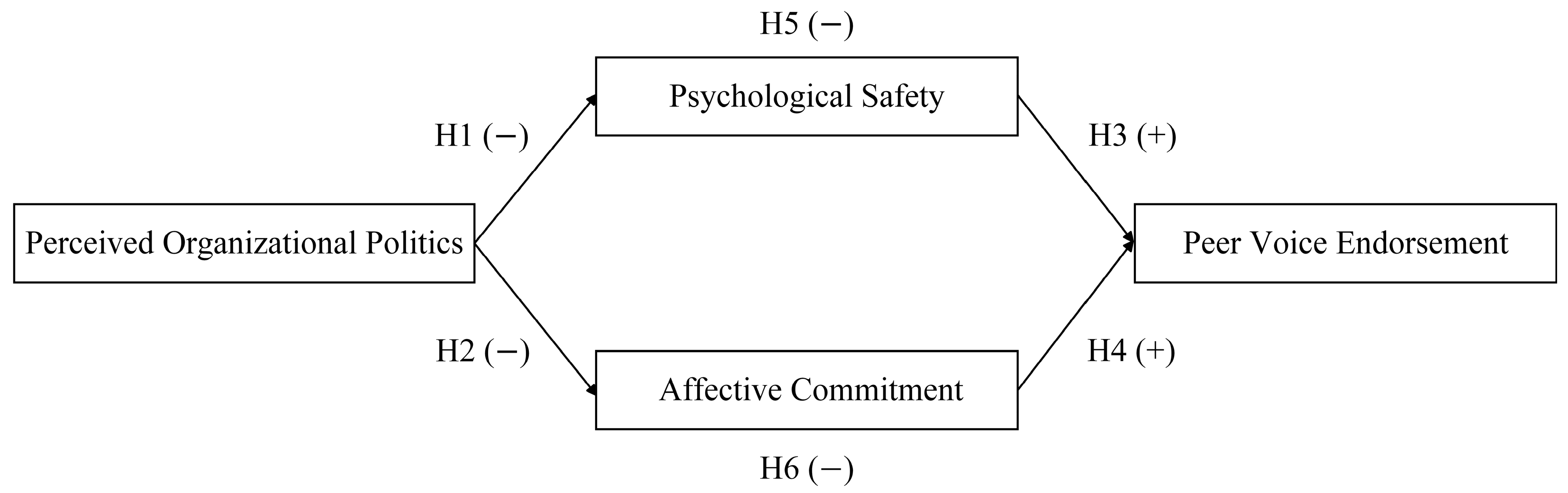

2.1. POP, Psychological Safety, and Affective Commitment

2.2. Psychological Safety, Affective Commitment, and Peer Voice Endorsement

2.3. The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety and Affective Commitment

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Common Method Bias Testing

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.2.1. Practical Implications for Organizations

5.2.2. Practical Implications for Leaders

5.2.3. Practical Implications for Employees

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Abrrow, H. A. (2022). The effect of perceived organisational politics on organisational silence through organisational cynicism: Moderator role of perceived support. Journal of Management & Organization, 28(4), 754–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. (2024). Knowledge transfer within organizations: Mechanisms, motivation, and consideration. Annual Review of Psychology, 75(1), 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M., Zheng, X., Huang, X., Jing, T., Yu, C., Li, S., & Zhang, Z. (2023). How serving helps leading: Mediators between servant leadership and affective commitment. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1170490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y., Han, G. H., & Harms, P. D. (2016). Team conflict mediates the effects of organizational politics on employee performance: A cross-level analysis in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(1), 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K., Kreps, T. A., Meikle, N. L., & Tenney, E. R. (2021). Amplifying voice in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 64(4), 1288–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, D. M., & Thompson, P. S. (2020). Speaking up at work: The role of perceived organizational support in explaining the relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and voice behavior. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 56(2), 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. S. (2006). Advice taking and decision-making: An integrative literature review, and implications for the organizational sciences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oraland written materials. Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Brykman, K. M., & Raver, J. L. (2023). Persuading managers to enact ideas in organizations: The role of voice message quality, peer endorsement, and peer opposition. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44(5), 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P. J., Clegg, J., & Tan, H. (2006). Cultural awareness in knowledge transfer to China—The role of guanxi and mianzi. Journal of World Business, 41(3), 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R. S. (2005). Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan, S., Unler, E., & Tatoglu, E. (2024). Commitment profiles for employee voice: Dual target and dominant commitment mindsets. Current Psychology, 43(2), 1696–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C. H., Rosen, C. C., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H., & Pak, J. (2024). When HRM meets politics: Interactive effects of high-performance work systems, organizational politics, and political skill on job performance. Human Resource Management Journal, 34(4), 1112–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Sun, X., Lu, J., & He, Y. (2022). How ethical leadership prompts employees’ voice behavior? The roles of employees’ affective commitment and moral disengagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 732463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y., Nudelman, G., Otto, K., & Ma, J. (2020). Belief in a just world and employee voice behavior: The mediating roles of perceived efficacy and risk. The Journal of Psychology, 154(2), 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. N., Hu, C., Wang, S., & Huang, J. C. (2024). Political context matters: A joint effect of coercive power and perceived organizational politics on abusive supervision and silence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41(1), 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinomona, R., & Chinomona, E. (2013). The influence of employees’ perceptions of organizational politics on turnover intentions in Zimbabwe’s SME sector. South African Journal of Business Management, 44(2), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, T., Van Dyne, L., & Lin, B. (2017). Too attached to speak up? It depends: How supervisor–subordinate guanxi and perceived job control influence upward constructive voice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 143, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2018). The roles of informational unfairness and political climate in the relationship between dispositional envy and job performance in Pakistani organizations. Journal of Business Research, 82, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, M. A. (2023). The effects of innovation climate on employee job satisfaction and affective commitment: Findings from public organizations. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 43(1), 130–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J. R., Burris, E. R., Harrison, D. A., & Martin, S. R. (2013). Voice flows to and around leaders: Understanding when units are helped or hurt by employee voice. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(4), 624–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J., Ran, M., & Cao, P. (2014). Context-contingent effect of Zhongyong on employee innovation behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 46(1), 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In R. M. Kramer, & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 239–272). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G. R., Ellen, B. P., McAllister, C. P., & Maher, L. P. (2019). Reorganizing organizational politics research: A review of the literature and identification of future research directions. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G. R., Harrell-Cook, G., & Dulebohn, J. H. (2000). Organizational politics: The nature of the relationship between politics perceptions and political behavior. In S. B. Bacharach, & E. J. Lawler (Eds.), Research in the sociology of organizations (pp. 89–130). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao-Urhahn, X., Biemann, T., & Jaros, S. J. (2016). How affective commitment to the organization changes over time: A longitudinal analysis of the reciprocal relationships between affective organizational commitment and income. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(4), 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J. F., Johnson, K. J., Roloff, K. S., & Edmondson, A. C. (2019). From orientation to behavior: The interplay between learning orientation, open-mindedness, and psychological safety in team learning. Human Relations, 72(11), 1726–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., & Li, T. (2021). Mediating model of college students’ Chinese Zhongyong culture thinking mode and depressive symptoms. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochwarter, W. A., Rosen, C. C., Jordan, S. L., Ferris, G. R., Ejaz, A., & Maher, L. P. (2020). Perceptions of organizational politics research: Past, present, and future. Journal of Management, 46(6), 879–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T. M., Harrison, D. A., Burris, E. R., & Detert, J. R. (2015). Who gets credit for input? Demographic and structural status cues in voice recognition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1765–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huai, M., Wen, X., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Li, W. D., & Wang, M. (2024). Does voice endorsement by supervisors enhance or constrain voicer’s personal initiative? Countervailing effects via feeling pride and feeling envied. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(9), 1408–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, T., Campbell, J. W., & Jeong, J. (2016). Commitment intensity in public organizations: Performance, innovation, leadership, and PSM. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(3), 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaakyan, S., Sherf, E. N., Tangirala, S., & Guenter, H. (2021). Keeping it between us: Managerial endorsement of public versus private voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(7), 1049–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, K. M., & Carlson, D. S. (1997). Further validation of the perceptions of politics scale (POPS): A multiple sample investigation. Journal of Management, 23(5), 627–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N., & Kang, L. S. (2022). Perception of organizational politics, knowledge hiding and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating effect of political skill. Personnel Review, 52(3), 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., & Chaudhary, R. (2022). Perceived organizational politics and workplace gossip: The moderating role of compassion. International Journal of Conflict Management, 34(2), 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. A., Khan, A. N., & Gul, S. (2019). Relationship between perception of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior: Testing a moderated mediation model. Asian Business & Management, 18(2), 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2020). Empowering leadership: Leading people to be present through affective organizational commitment? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(16), 2017–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T. (2013). The moderating effects of political skill and leader–member exchange on the relationship between organizational politics and affective commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. F., Lee, C., & Sui, Y. (2019). Say it as it is: Consequences of voice directness, voice politeness, and voicer credibility on voice endorsement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(5), 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landells, E. M., & Albrecht, S. L. (2017). The positives and negatives of organizational politics: A qualitative study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(1), 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landells, E. M., & Albrecht, S. L. (2019). Perceived organizational politics, engagement, and stress: The mediating influence of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C., Liang, J., & Farh, J. L. (2020). Speaking up when water is murky: An uncertainty-based model linking perceived organizational politics to employee voice. Journal of Management, 46(3), 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Wu, L. Z., Liu, D., Kwan, H. K., & Liu, J. (2014). Insiders maintain voice: A psychological safety model of organizational politics. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(3), 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Shu, R., & Farh, C. I. (2019). Differential implications of team member promotive and prohibitive voice on innovation performance in research and development project teams: A dialectic perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Tian, G., Zhang, X., & Tian, Y. (2024). New voice channel and voice endorsement: How the information displayed on online idea management platforms influences voice endorsement? International Journal of Business Communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Yuan, Q., & Luo, J. (2025). Technical anonymity and employees’ willingness to speak up: Influences of voice solicitation, general timeliness, and psychological safety. Management Communication Quarterly, 39(2), 322–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Li, D., & Zhang, X. (2022). Threat from peers: The effect of leaders’ voice endorsement on coworkers’ self-improvement motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 724130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Zhu, R., & Yang, Y. (2010). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, L. R., Sharma, D., Ghosh, K., & Sahu, A. K. (2024). Impact of organizational politics on employee outcomes: A systematic literature review. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(4), 714–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, C. C. (1986). Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory of self-influence processes in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, C. P., Ellen, B. P., III, & Ferris, G. R. (2018). Social influence opportunity recognition, evaluation, and capitalization: Increased theoretical specification through political skill’s dimensional dynamics. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1926–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M. S., Jian, Z., Akram, U., Akram, Z., & Tanveer, Y. (2021). Entrepreneurial leadership and team creativity: The roles of team psychological safety and knowledge sharing. Personnel Review, 51(9), 2404–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisler, G., Drory, A., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2019). Perceived organizational politics and counterproductive work behavior: The mediating role of hostility. Personnel Review, 49(8), 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102(2), 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W. (2023). Employee voice and silence: Taking stock a decade later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, P. K., Gu, J., Chen, Z., Tse, H. H., & Wilkinson, A. (2024). How do tangible and intangible rewards encourage employee voice? The perspective of dual proactive motivational pathways. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(15), 2569–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W., Lucianetti, L., Hsu, D. Y., Yim, F. H., & Sorensen, K. L. (2021). You speak, I speak: The social-cognitive mechanisms of voice contagion. Journal of Management Studies, 58(6), 1569–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, D., Yang, M., & Chen, W. (2024). A dual-path model of observers’ responses to peer voice endorsement: The role of instrumental attribution. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, M. J., & Ellis, A. P. (2011). Thick as thieves: The effects of ethical orientation and psychological safety on unethical team behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, E. C., Lin, S. H., Fatimah, S., Ho, C. M., Ferris, D. L., & Johnson, R. E. (2024). My manager endorsed my coworkers’ voice: Understanding observers’ positive and negative reactions to managerial endorsement of coworker voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(8), 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saei, E., & Liu, Y. (2024). No news is not good news: The mediating role of job frustration in the perceptions of organizational politics and employee silence. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 60(3), 520–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H., Fu, H., Ge, Y., Jia, W., Li, Z., & Wang, J. (2022). Moderating effects of transformational leadership, affective commitment, job performance, and job insecurity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 847147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherf, E. N., Parke, M. R., & Isaakyan, S. (2021). Distinguishing voice and silence at work: Unique relationships with perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout. Academy of Management Journal, 64(1), 114–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M., Zhong, Z., & Ren, H. (2022). Voice contributes to creativity via leaders’ endorsement especially when proposed by extraverted high performance employees. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, R., & Vîrgă, D. (2021). Psychological needs matter more than social and organizational resources in explaining organizational commitment. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(4), 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W., & Xie, C. (2023). The impact of organizational politics on work engagement—The mediating role of the doctrine of the mean. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1283855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y., Lu, X., Choi, J. N., & Guo, W. (2019). Ethical leadership and team-level creativity: Mediation of psychological safety climate and moderation of supervisor support for creativity. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, S., & Turner, N. (2015). Sometimes it hurts when supervisors don’t listen: The antecedents and consequences of safety voice among young workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(1), 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. (2001). Reactions to organizational politics: A cross-cultural examination in Israel and Britain. Human Relations, 54(11), 1483–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. (2002). Stress-related aftermaths to workplace politics: The relationships among politics, job distress, and aggressive behavior in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(5), 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Talmud, I. (2010). Organizational politics and job outcomes: The moderating effect of trust and social support. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(11), 2829–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Liu, Y., Lou, Z., & Chen, Y. (2025). The double-edged sword of workplace friendship: Exploring when and how workplace friendship promotes versus inhibits voice behavior. The Journal of General Psychology, 152(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Dai, Y., Li, H., & Song, L. (2021). Social media and attitude change: Information booming promote or resist persuasion? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 596071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M., & Morrison, E. W. (2019). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S. W., Maynes, T. D., Podsakoff, N. P., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Effects of message, source, and context on evaluations of employee voice behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S., Kee, D. M. H., Li, D., & Ni, D. (2021). Thanks for your recognition, boss! A study of how and when voice endorsement promotes job performance and voice. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 706501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., Qin, X., Dust, S. B., & DiRenzo, M. S. (2019). Supervisor-subordinate proactive personality congruence and psychological safety: A signaling theory approach to employee voice behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(4), 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X., Wu, J., & Jie, Y. (2025). How and when psychological safety impacts employee innovation: The roles of thriving at work and regulatory focus. Current Psychology, 44(5), 3736–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Chen, H. (2024). From opportunity to threat: The non-linear relationship between voice frequency and job performance via voice endorsement. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 62(1), e12368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N., He, B., & Sun, X. (2024). The contagion of ethical voice among peers: An attribution perspective. Current Psychology, 43(27), 23191–23202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., & Sun, J. (2024). Perceived organizational politics and employee voice: The role of affect and supervisor political support. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 39(7), 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., & Sun, J. (2025). Perceived organizational politics and employee voice: A resource perspective. Journal of Business Research, 186, 114935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 120 | 53.1% |

| Female | 106 | 46.9% | |

| Age | Below 30 | 111 | 49.1% |

| 31−40 | 95 | 42.0% | |

| 41−50 | 19 | 8.4% | |

| Above 50 | 1 | 0.5% | |

| Organizational tenure | Below 1 year | 32 | 14.2% |

| 1−3 years | 48 | 21.2% | |

| 3−5 years | 51 | 22.5% | |

| 5−10 years | 63 | 27.9% | |

| Over 10 years | 32 | 14.2% |

| Model | Model Structure | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | POP; PS; AC; PVE; ZY | 786.32 | 454 | 1.73 | 0.06 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Four-factor model 1 | POP + ZY; PS; AC; PVE | 1135.16 | 458 | 2.48 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Four-factor model 2 | POP; PS + AC; PVE; ZY | 946.26 | 458 | 2.07 | 0.07 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.81 |

| Three-factor model | POP + ZY; PS + AC; PVE | 1293.18 | 461 | 2.81 | 0.09 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

| Single factor model | POP + PS + AC + PVE + ZY | 2256.83 | 464 | 4.86 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.47 | 0.50 | - | |||||||

| 2. Age | 32.20 | 5.24 | −0.28 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Organizational tenure | 6.02 | 4.87 | −0.10 | 0.61 ** | - | |||||

| 4. Zhongyong | 4.09 | 0.47 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.13 | (0.80) | ||||

| 5. POP | 2.52 | 0.88 | −0.05 | −0.17 * | −0.02 | −0.03 | (0.89) | |||

| 6. Psychological safety | 3.32 | 0.64 | −0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.20 ** | −0.32 ** | (0.80) | ||

| 7. Affective commitment | 3.58 | 0.92 | −0.05 | 0.22 ** | 0.09 | 0.16 * | −0.56 ** | 0.54 ** | (0.94) | |

| 8. Peer voice endorsement | 3.65 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.20 ** | −0.13 | 0.30 ** | 0.35 ** | (0.85) |

| Independent Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Safety | Affective Commitment | Peer Voice Endorsement | |

| Gender | −0.15 * | −0.05 | 0.13 * |

| Age | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Organizational tenure | 0.09 | −0.01 | −0.08 |

| Zhongyong | 0.20 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.11 |

| POP | −0.32 *** | −0.55 *** | 0.12 |

| Psychological safety | 0.16 * | ||

| Affective commitment | 0.30 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.18 |

| F | 8.56 *** | 24.38 *** | 6.88 *** |

| Indirect Path | Indirect Effect | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| POP-Psychological Safety-Peer Voice Endorsement | −0.06 * | −0.10 | −0.03 |

| POP-Affective Commitment-Peer Voice Endorsement | −0.13 * | −0.19 | −0.08 |

| Hypothesis Number | Hypothesis Statement | Supported/Not Supported |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Perceived organizational politics has a negative impact on employees’ psychological safety. | Supported |

| H2 | Perceived organizational politics has a negative impact on employees’ affective commitment. | Supported |

| H3 | Employees’ psychological safety has a positive impact on peer voice endorsement. | Supported |

| H4 | Employees’ affective commitment has a positive impact on peer voice endorsement. | Supported |

| H5 | Psychological safety mediates the relationship between perceived organizational politics and peer voice endorsement. | Supported |

| H6 | Affective commitment mediates the relationship between perceived organizational politics and peer voice endorsement. | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, P.; Chen, T.; Hu, L.; Zhou, H. The Impact of Perceived Organizational Politics on Peer Voice Endorsement: A Dual Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070892

Qiu P, Chen T, Hu L, Zhou H. The Impact of Perceived Organizational Politics on Peer Voice Endorsement: A Dual Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):892. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070892

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Peiwen, Tingjing Chen, Liao Hu, and Hao Zhou. 2025. "The Impact of Perceived Organizational Politics on Peer Voice Endorsement: A Dual Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070892

APA StyleQiu, P., Chen, T., Hu, L., & Zhou, H. (2025). The Impact of Perceived Organizational Politics on Peer Voice Endorsement: A Dual Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 892. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070892