The Relationship Between Negative Life Events and Mental Health in Chinese Vulnerable Children: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

Moderator Variable

2. Materials and Methods

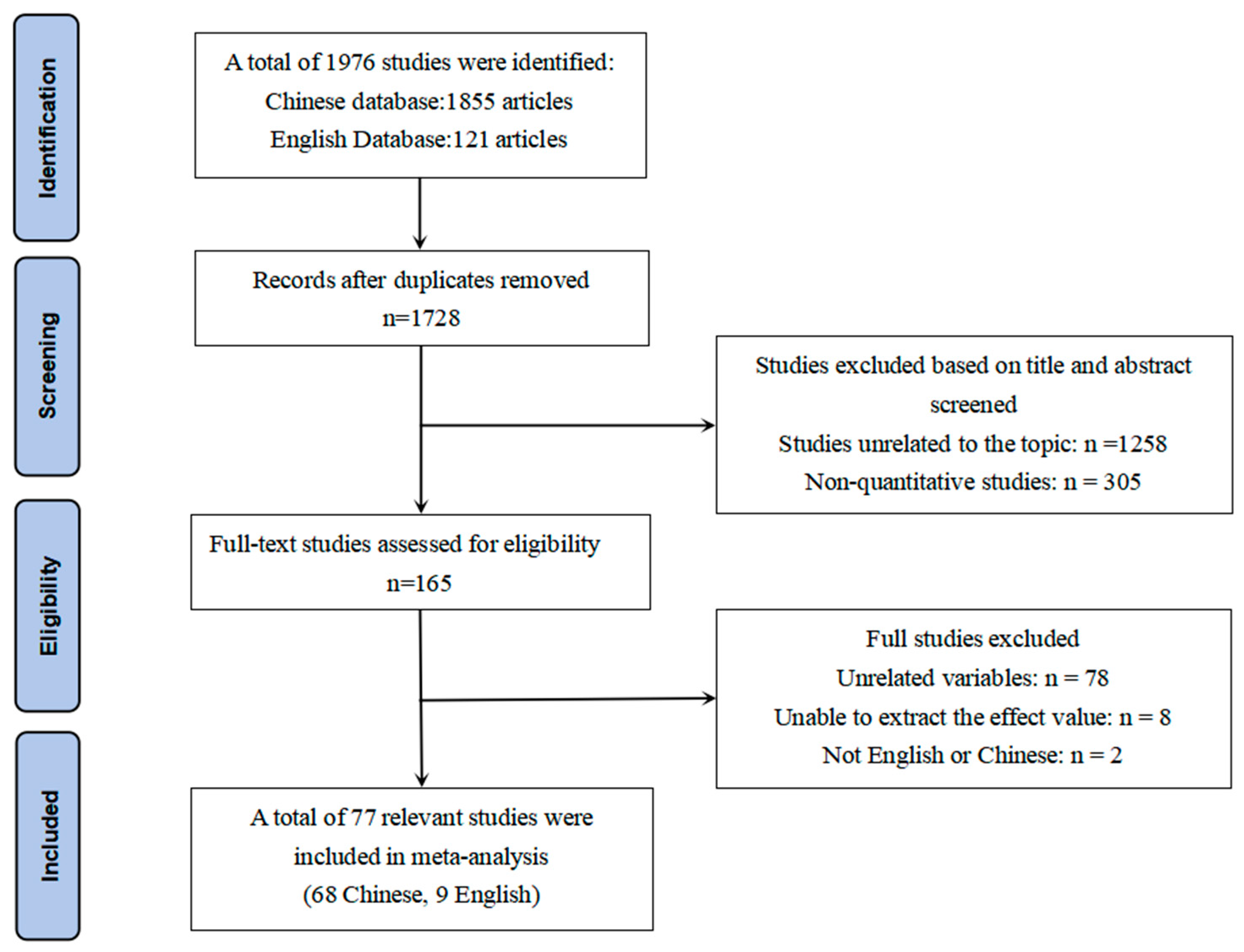

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Literature Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Literature Coding

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Literature Inclusion and Quality Assessment

3.2. Publication Bias Test

3.3. Heterogeneity Test

3.4. Main Effects Test

3.5. Relative Weight Analysis

3.6. Analysis of Moderating Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Effects of Negative Life Events on Mental Health in Vulnerable Children

4.2. Moderating Role of Correlates in the Relationship Between Negative Life Events and Mental Health Among Vulnerable Children

4.3. Implications

4.4. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abela, J., & Skitch, S. (2007). Dysfunctional attitudes, self-esteem, and hassles: Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children of affectively ill parents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(6), 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T. M., Ivanova, M. Y., Rescorla, L. A., Turner, L. V., & Althoff, R. R. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(8), 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagge, C. L., Glenn, C. R., & Lee, H. J. (2013). Quantifying the impact of recent negative life events on suicide attempts. J. Abnorm. Psychol, 122(2), 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H., Zhao, L., & Wu, X. (2014). The impact of life events on emotional reactions and behavior options: Theory comparison and research implications. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(3), 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. W. L. (2014). Modeling dependent effect sizes with three-level meta-analyses: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China National Children’s Center. (2024). Annual report on Chinese children’s development (3rd ed.). Social Sciences Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P., Smit, F., Unger, F., Stikkelbroek, Y., Ten Have, M., & de Graaf, R. (2011). The disease burden of childhood adversities in adults: A population-based study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(11), 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. W., Li, D., & Whipple, S. S. (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., Zhang, W., Dong, Y., & Chen, G. (2025). Parental control and adolescent social anxiety: A focus on emotional regulation strategies and socioeconomic influences in China. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 43(1), 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., Yao, Y., Yao, C., Xiong, Y., Ma, H., & Liu, H. (2019). The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem between negative life events and positive social adjustment among left-behind adolescents in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Guo, L., He, S., Liu, C., & Luo, L. (2020). Mothers’ filial piety and children’s academic achievement: The indirect effect via mother-child discrepancy in perceived parental expectations. Educational Psychology, 40(10), 1230–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L., Yuan, J., & Long, Y. (2021). Will moss bloom like peonies? The relationship between negative life ev-ents and mental health of left-behind children. Psychological Development and Education, 37(2), 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L., Yuan, J., & Zhao, Q. (2019). The impact of life events on mental health of rural left-behind children: The mediating role of peer attachment and psychological resilience and the moderating role of sense of security. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 26(7), 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y., Wen, H., Cheng, S., Zhang, C., & Li, X. (2020). Relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health of migrant children: A meta-analysis of Chinese students. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(11), 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Liao, C., Xu, H., Hu, Y., Chen, Q., & Du, H. (2016). Life events and mental health of left-behind children of overseas Chinese: The role of sense of security. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics, 33(1), 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. M., & Doolittle, E. J. (2017). Social and emotional learning: Introducing the issue. The Future of Children, 27(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhina, K., Bøe, T., Hysing, M., & Nilsen, S. A. (2023). Parental separation, negative life events and mental health problems in adolescence. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Lopez, S. J. (2002). Toward a science of mental health: Positive directions in diagnosis and interventions. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 45–59). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Ryff, C. D. (1999). Psychological well-being in midlife. In Life in the middle (pp. 161–180). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F., & Jhang, F. (2023). Controllable negative life events, family cohesion, and externalizing problems among rural and migrant children in China: A moderated mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 147, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K., Zhang, T., Ma, P., Mo, M., & Pan, W. (2023). The relationship between life events and anxious emotion of adolescents in poverty alleviation relocated areas: The mediating effects of coping style and social support. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(5), 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N., & Zhuang, Y. (2022). The relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health: The relati-onship between perceived discrimination and mental health. Educational Research and Experiment, 1, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Li, Y., Gui, W., & Mao, Y. (2023). Impact of life events on subjective happiness of left-behind secondary school students in rural areas. Teaching & Administration, 40(21), 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C., Wu, J., & Zhang, J. (2015). A factor analysis of the mental health of children left behind: Perspective of sense of security. Journal of East China Normal University (Educational Sciences), 33(3), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M., & Wilson, D. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. SAGE publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, R. K. (2020). A Meta-analysis of the relationship between negative life events and depressive symptoms of Chinese middle school students. Journal of Shanghai Educational Research, 40(3), 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Civil Affairs, Ministry of Education, National Health Commission & Central Committee of the Communist Youth League. (2023). Guiding opinions on strengthening the mental health care and service for children in difficult circumstances. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202311/content_6913516.htm (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Peng, S., Li, H., Xu, L., Chen, J., & Cai, S. (2023). Burden or empowerment? A double-edged sword model of the efficacy of parental involvement in the academic performance of Chinese adolescents. Current Psychology, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, M. R., Stienwandt, S., Giuliano, R., Penner-Goeke, L., Fisher, P. A., & Roos, L. E. (2020). Stress system reactivity moderates the association between cumulative risk and children’s externalizing symptoms. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 158, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y., & Fu, Z. (2021). Research on the relationship among life events, stress coping, and post- stress growth of children in difficulties. Survey of Education, 10(40), 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suldo, S. M., & Shaffer, E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Second National Sampling Survey on Disability Leadership Group & National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. (2006). The second national sampling survey on disability: Major data bulletin. Available online: https://www.cdpf.org.cn//zwgk/zccx/dcsj/9ff8c67574af479dabaf6ac21b5305f4.htm (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. (2016). Opinions of the state council on strengthening the care and protection of the left-behind children in rural areas. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2016/content_5086312.htm (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Tong, X. (2020). Research on the resilience model intervention for high-risk adolescents: A qualitative analysis based on disadvantaged children in northwest China. Social Science Research, 5, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fun. (2023). Child multidimensional poverty in China (2013–2018). Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/reports/child-multidimensional-poverty-china (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Wang, C., & Yang, Y. (2016). Research on the relationship between psychological resilience and life events of poverty-stricken students. Teacher Education Forum, 29(2), 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. L., Feldman, J. S., Lemery-Chalfant, K., Wilson, M. N., & Shaw, D. S. (2019). Family-based prevention of adolescents’ co-occurring internalizing/externalizing problems through early childhood parent factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(11), 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., & Liu, T. (2018). Life events and mental health of left-behind Children in shanbei region: The intermediary effect of coping style. China Journal of Health Psychology, 26(3), 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Xiong, Y., & Liu, X. (2020). Family unity or money? The roles of parent-child cohesion and socioeconomic status in the relationship between stressful life events and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese left-behind children. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 50(5), 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (1948). Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Xiao, J., Liang, K., Huang, L., Wang, E., Huang, Q., He, Y., Lu, B., & Chi, X. (2024). The cumulative effects, Relationship model, and the effects of specific positive development assets in reducing adolescent depression. Psychological Development and Education, 40(2), 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H., Liu, X., Wang, X., Tu, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, D. (2016). Effect of negative life events on female students’ mental health: Moderated mediating effect. Journal of Nanchang Normal University, 37(6), 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J., Hai, M., Huang, F., Xin, L., & Xu, Y. (2020). Family cumulative risk and mental health in Chinese adolescents: The compensatory and moderating effects of psychological capital. Psychological Development and Education, 36(1), 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Liu, H., & Zhou, N. (2016). Life events and mental health in floating children: Moderation of social support. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(6), 1120–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W., Jiang, Z. J., Liu, Y. F., Chen, Z. Y., Chu, X. H., & Song, Y. (2024). Comprehensively strengthen and improve students’ mental health system in the New Era. China CDC Weekly, 6(29), 719–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. (2024). Parent-child expectation discrepancy and adolescent mental health: Evidence from “China education panel survey”. Child Indicators Research, 17(2), 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S., Wang, J., Lu, S., & Xiao, J. (2024). A longitudinal investigation of the cross-dimensional mediating role of negative life events between neuroticism and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 355, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y., Lyu, C., & Xu, F. (2013). On the relationship between left-at-home rural children’s resilience and mental health. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 20(10), 52–59. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | k | n | Fail-Safe | Intercept | 95% Confidence Interval | Two-Tailed Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | t | p | |||||

| Negative Mental Health | 51 | 40,214 | 89,069 | 0.38 | −3.32 | 4.09 | 0.21 | 0.843 |

| Positive Mental Health | 69 | 74,594 | 65,319 | 1.51 | −0.54 | 3.56 | 1.47 | 0.151 |

| Variable | k | Heterogeneity Q Test | Tau-Squared | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | df (Q) | p | I2 | Tau-Squared | SE | Variance | Tau | ||

| Negative Mental Health | 51 | 1308.23 | 49 | <0.001 | 96.25% | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.18 |

| Positive Mental Health | 69 | 1411.75 | 68 | <0.001 | 95.18% | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Variable | k | r | 95% Confidence Interval | Two-Tailed Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | Z | p | |||

| Negative Mental Health | 50 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 16.98 | <0.001 |

| Positive Mental Health | 69 | −0.25 | −0.28 | −0.21 | −14.27 | <0.001 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Interpersonal problems (K, N) | 1 | 0.63 *** (5, 3286) | 0.65 *** (5, 3286) | 0.41 *** (5, 3286) | 0.52 *** (5, 3286) | 0.55 *** (5, 3286) |

| 2. Study stress (K, N) | 0.63 *** (8, 4019) | 1 | 0.65 *** (5, 3286) | 0.37 *** (5, 3286) | 0.50 *** (5, 3286) | 0.48 *** (5, 3286) |

| 3. Punishment (K, N) | 0.63 *** (8, 4019) | 0.62 *** (8, 4019) | 1 | 0.47 *** (5, 3286) | 0.53 *** (5, 3286) | 0.70 *** (5, 3286) |

| 4. Loss (K, N) | 0.50 *** (8, 4019) | 0.46 *** (8, 4019) | 0.56 *** (8, 4019) | 1 | 0.47 *** (5, 3286) | 0.34 *** (5, 3286) |

| 5. Health adaptation (K, N) | 0.52 *** (8, 4019) | 0.53 *** (8, 4019) | 0.54 *** (8, 4019) | 0.53 *** (8, 4019) | 1 | 0.50*** (5, 3286) |

| 6. Other stresses (K, N) | 0.57 *** (6, 3068) | 0.50 *** (6, 3068) | 0.71 *** (6, 3068) | 0.46 *** (6, 3068) | 0.55 *** (6, 3068) | 1 |

| Independent Variable | Negative Mental Health | Positive Mental Health | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | %R2 | W | %R2 | |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.08 | 32.20 | 0.02 | 23.84 |

| Academic Stress | 0.06 | 24.21 | 0.01 | 14.91 |

| Punishment | 0.02 | 8.62 | 0.01 | 11.17 |

| Loss | 0.02 | 6.33 | 0.00 | 2.44 |

| Health Adaptation | 0.02 | 11.37 | 0.01 | 10.84 |

| Other Stressors | 0.04 | 17.27 | 0.03 | 36.80 |

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.07 | ||

| Moderator | Heterogeneity Test | Category | k | 95% CI | Two-Tailed Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qb | df | p | Point Estimate | LL | UL | Z | p | |||

| Type of Vulnerable Children | 3.08 | 3 | 0.381 | Left-Behind | 31 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 12.84 | <0.001 |

| Migrant | 9 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 6.88 | <0.001 | ||||

| Impoverished | 8 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 8.22 | <0.001 | ||||

| Disabled | 3 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.66 | 3.80 | <0.001 | ||||

| Type of Outcome Variable | 4.97 | 4 | 0.294 | Composite Symptoms | 18 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.52 | 11.04 | <0.001 |

| Behavioral Issues | 7 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 4.46 | <0.001 | ||||

| Depression | 17 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 10.18 | <0.001 | ||||

| Anxiety | 5 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 5.35 | <0.001 | ||||

| Other | 4 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 4.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| Educational Stage | 0.07 | 2 | 0.972 | Primary School | 3 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.58 | 3.98 | <0.001 |

| Secondary School | 29 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 8.05 | <0.001 | ||||

| Combined Schools | 18 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 9.72 | <0.001 | ||||

| Source of Negative Life Events | 26.89 | 5 | <0.001 | Interpersonal Issues | 26 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 15.83 | <0.001 |

| Academic Stress | 26 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 14.30 | <0.001 | ||||

| Punishment | 26 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 11.45 | <0.001 | ||||

| Loss | 25 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 9.03 | <0.001 | ||||

| Health Adaptation | 26 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 11.48 | <0.001 | ||||

| Other Stressors | 22 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 11.76 | <0.001 | ||||

| Moderator | Heterogeneity Test | Category | k | 95% CI | Two-Tailed Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qb | df | p | Point Estimate | LL | UL | Z | p | |||

| Type of Vulnerable Children | 3.77 | 3 | 0.293 | Left-Behind | 50 | −0.26 | −0.30 | −0.22 | −12.77 | <0.001 |

| Migrant | 13 | −0.25 | −0.32 | −0.17 | −6.21 | <0.001 | ||||

| Impoverished | 5 | −0.16 | −0.28 | −0.03 | −2.35 | <0.001 | ||||

| Type of Outcome Variable | 21.55 | 7 | 0.003 | Social Support | 15 | −0.18 | −0.25 | −0.12 | −5.35 | <0.001 |

| Life Satisfaction | 4 | −0.32 | −0.43 | −0.20 | −4.90 | <0.001 | ||||

| Adaptive Behavior | 6 | −0.21 | −0.31 | −0.20 | −8.44 | <0.001 | ||||

| Psychological Resilience | 19 | −0.26 | −0.32 | −0.20 | −8.44 | <0.001 | ||||

| Psychological Capital | 5 | −0.39 | −0.48 | −0.28 | −6.65 | <0.001 | ||||

| Well-Being | 7 | −0.36 | −0.44 | −0.26 | −7.16 | <0.001 | ||||

| Self-Esteem | 7 | −0.22 | −0.31 | −0.12 | −4.34 | <0.001 | ||||

| Other | 6 | −0.15 | −0.25 | −0.04 | −2.62 | <0.001 | ||||

| Educational Stage | 1.32 | 2 | 0.521 | Primary School | 4 | −0.32 | −0.44 | −0.18 | −4.42 | <0.001 |

| Secondary School | 46 | −0.25 | −0.29 | −0.21 | −11.60 | <0.001 | ||||

| Combined Schools | 19 | −0.23 | −0.29 | −0.17 | −7.14 | <0.001 | ||||

| Source of Negative Life Events | 18.85 | 5 | 0.002 | Interpersonal Problems | 25 | −0.23 | −0.28 | −0.18 | −8.74 | <0.001 |

| Academic Stress | 25 | −0.21 | −0.26 | −0.16 | −7.69 | <0.001 | ||||

| Punishment | 25 | −0.19 | −0.24 | −0.14 | −7.12 | <0.001 | ||||

| Loss | 25 | −0.10 | −0.16 | −0.05 | −3.81 | <0.001 | ||||

| Health Adaptation | 25 | −0.17 | −0.23 | −0.12 | −6.44 | <0.001 | ||||

| Other Stressors | 23 | −0.25 | −0.30 | −0.20 | −8.92 | <0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, X. The Relationship Between Negative Life Events and Mental Health in Chinese Vulnerable Children: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070882

Pu Y, Zhang K, Jiang X. The Relationship Between Negative Life Events and Mental Health in Chinese Vulnerable Children: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):882. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070882

Chicago/Turabian StylePu, Yunrong, Kuo Zhang, and Xiaoliu Jiang. 2025. "The Relationship Between Negative Life Events and Mental Health in Chinese Vulnerable Children: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070882

APA StylePu, Y., Zhang, K., & Jiang, X. (2025). The Relationship Between Negative Life Events and Mental Health in Chinese Vulnerable Children: A Meta-Analysis Based on the Dual-Factor Model of Mental Health. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070882