Phubbed and Furious: Narcissists’ Responses to Perceived Partner Phubbing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotional and Behavioural Responses to Perceived Partner Phubbing

1.2. Narcissism and Its Role in Romantic Relationships

1.3. Narcissism and Phubbing: Research Gaps and Current Study Focus

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Daily Perceived Phubbing

2.3.2. Daily Relationship Satisfaction

2.3.3. Daily Self-Esteem

2.3.4. Daily Depressed/Anxious Mood

2.3.5. Daily Anger/Frustration

2.3.6. Daily Responses to Being Phubbed

2.3.7. Daily Motivations for Retaliation

2.3.8. Narcissism

2.3.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Daily Relationship Satisfaction, Personal Well-Being, and Anger/Frustration

3.2. Daily Responses to Being Phubbed

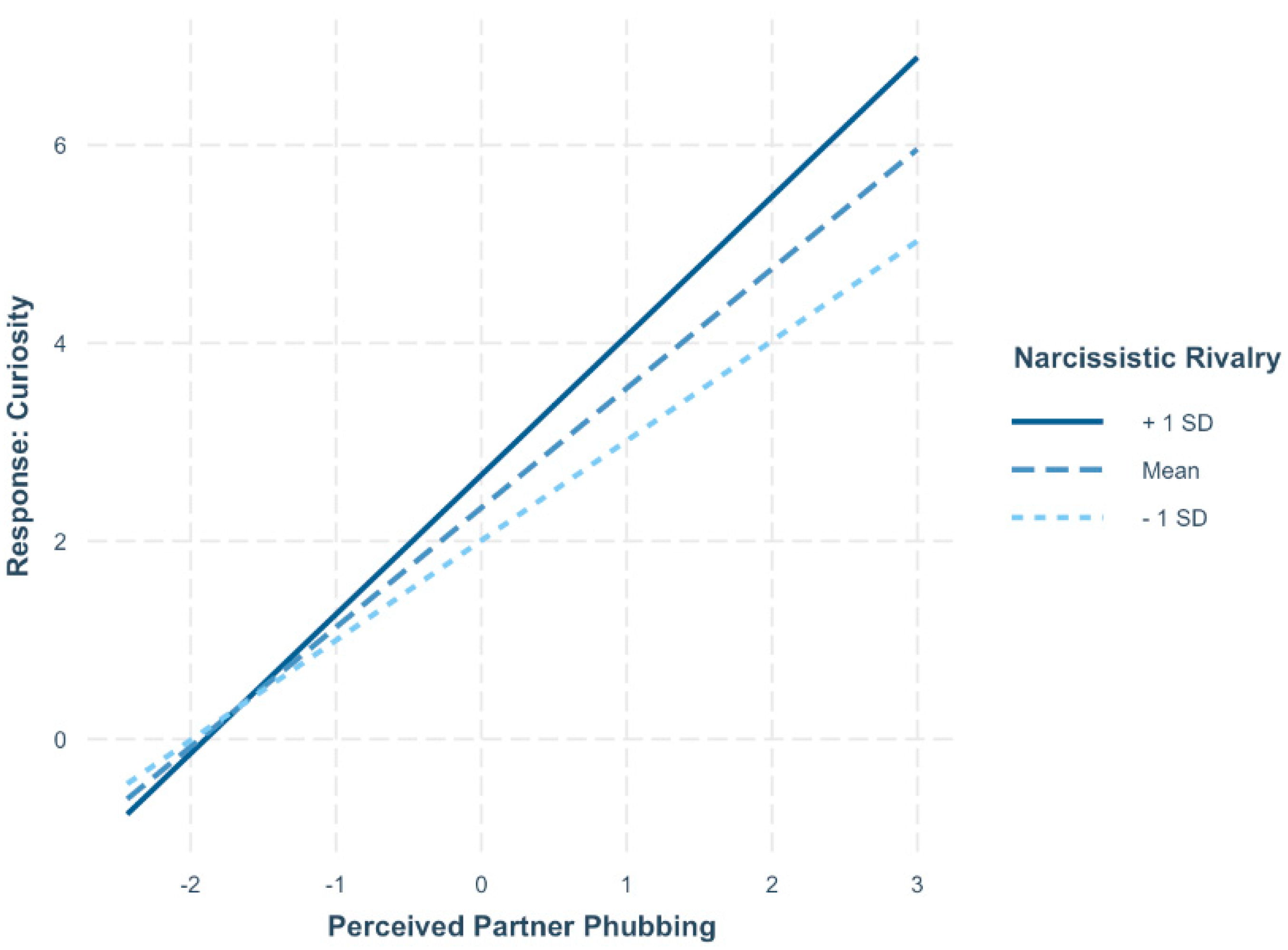

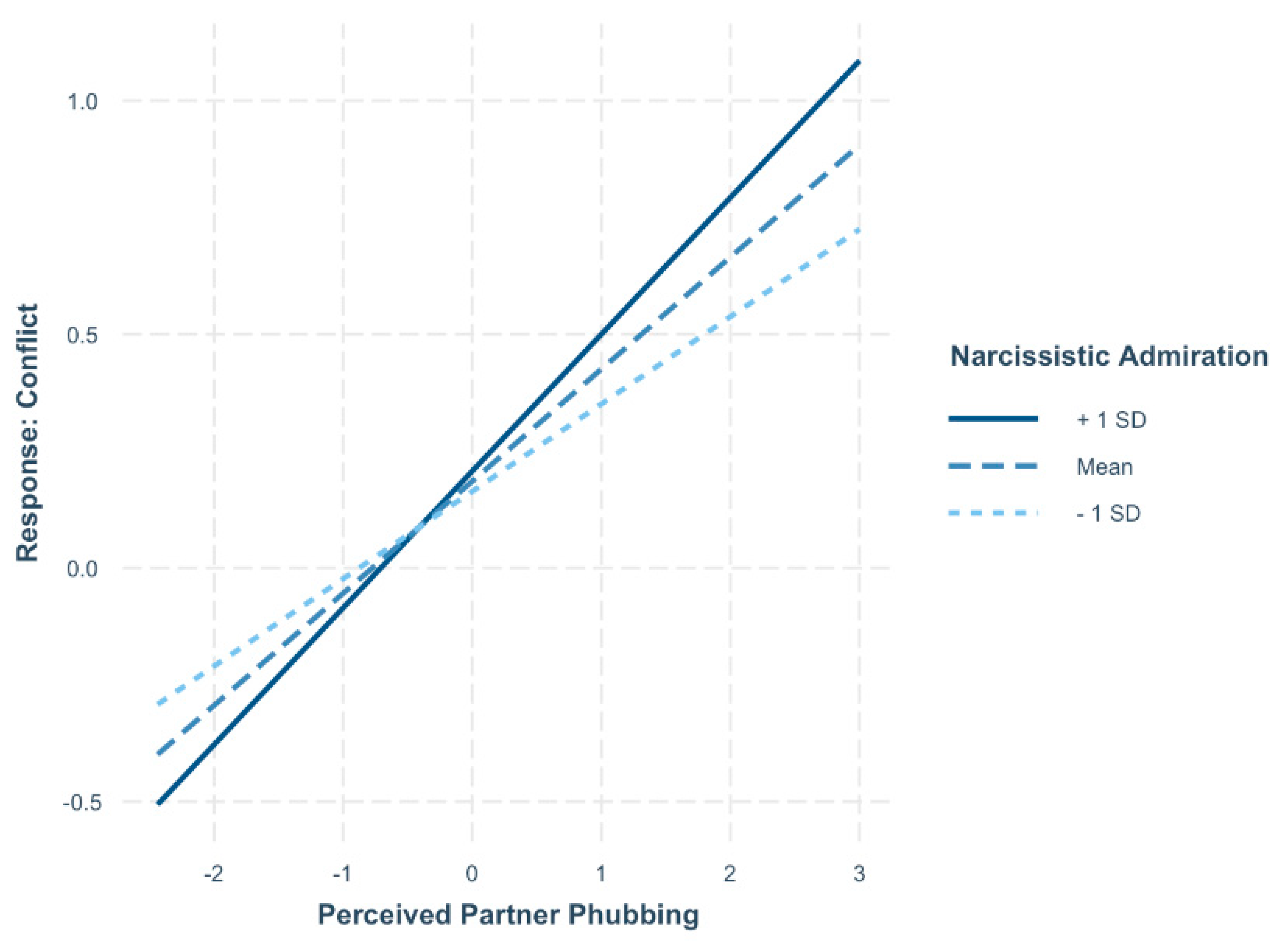

3.3. Daily Motivations for Retaliation

4. Discussion

4.1. Daily Relationship Satisfaction, Personal Well-Being, and Anger/Frustration

4.2. Daily Responses to Being Phubbed

4.3. Daily Motivations for Retaliation

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In a deviation from our pre-registered report, we included responses to perceived partner phubbing that were wider than just retaliation. Originally, we had conceived that all responses would be aggregated and represent an overall retaliatory variable, but the responses were quite disparate and did not correlate highly with one another. |

| 2 | In Thomas et al. (2022), we reported results from a smaller subsample of this current sample (N = 75) focusing on phubbing’s impact on well-being and retaliation motives, but not on narcissism. These results had sufficient statistical power (power = 0.80, α = 0.05) and were subsequently published. Later, with additional funding, we expanded our sample to be able to test the moderating effects of individual difference variables. In the footnotes, we note when the results from the larger sample (N = 196) replicate the earlier findings; however, the current hypotheses were not tested in the previous study. |

| 3 | We compared the Prolific and social media participants based on demographic and psychological characteristics. Independent-samples t-tests revealed that participants in the Prolific group were significantly older (M = 40.30, SD = 11.96) than those recruited via social media (M = 30.99, SD = 9.85) (t(187.72) = 5.92, p < 0.001) and had significantly longer relationship durations (M = 14.84, SD = 10.48) compared to social media participants (M = 6.93, SD = 6.92) (t(191.19) = 6.35, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in narcissistic admiration (M = 3.49, SD = 1.19 vs. M = 3.84, SD = 1.26, t(172.96) = −1.97, p = 0.051) or rivalry (M = 2.26, SD = 1.02 vs. M = 2.33, SD = 1.04, t(176.63) = −0.48, p = 0.63) between the Prolific and social media participants. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. No significant difference was found in gender distribution between groups (Fisher’s exact p = 0.31). However, there were significant group differences for sexual orientation (Fisher’s exact p < 0.001), relationship status (Fisher’s exact p < 0.001), and having children (χ2 = 23.88, p < 0.001). Social media participants were more likely to identify as bisexual or another minority sexual orientation, less likely to be married, and less likely to have children, whereas the Prolific participants were predominantly heterosexual, more often married, and more likely to have children. |

| 4 | The focus of this paper is on the individual difference variable of narcissism only. Data pertaining to the attachment measures will be reported in a separate paper. |

| 5 | These findings align with those reported in Thomas et al. (2022) based on the smaller sample, with the exception that the results for depressed and anxious mood were non-significant in the smaller sample. |

| 6 | These findings align with those reported in Thomas et al. (2022) based on the smaller sample, with the exception that the results for conflict and ignore were non-significant in the smaller sample. |

| 7 | These findings align with those reported in Thomas et al. (2022) based on the smaller sample, with the exception that the results for boredom were non-significant in the smaller sample. |

References

- Aagaard, J. (2020). Digital akrasia: A qualitative study of phubbing. AI and Society, 35(1), 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, I. (2018). Social media and committed relationships: What factors make our romantic relationship vulnerable? Social Science Computer Review, 37(3), 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akat, M., Arslan, C., & Hamarta, E. (2023). Dark triad personality and phubbing: The mediator role of FOMO. Psychological Reports, 126(4), 1803–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arican-Dinc, B., & Gable, S. L. (2023). Responsiveness in romantic partners’ interactions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, M., Küfner, A., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T., Rauthmann, J., & Denissen, J. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 1013–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beukeboom, C., & Pollmann, M. (2021). Partner phubbing: Why using your phone during interactions with your partner can be detrimental for your relationship. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G., Hunt, D., James, G., & Abell, L. (2015). Dark Triad traits, infidelity and romantic revenge. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, B. J., Bonacci, A. M., van Dijk, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Narcissism, sexual refusal, and aggression: Testing a narcissistic reactance model of sexual coercion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2002). Narcissism and commitment in romantic relationships: An investment model analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(4), 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2011). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides, & S. J. Spencer (Eds.), The self (pp. 115–138). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carnelley, K. B., Vowels, L. M., Stanton, S., Millings, A., & Hart, C. M. (2023). Perceived partner phubbing predicts lower relationship quality but partners’ enacted phubbing does not. Computers and Human Behavior, 147, 107860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshure, A., Zeigler-Hill, V., Sauls, D., Vrabel, J., & Lehtman, M. (2020). Narcissism and emotion dysregulation: Narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry have divergent associations with emotion regulation difficulties. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K., Atkinson, B. E., Raheb, H., Harris, E., & Vernon, P. A. (2016). The dark side of romantic jealousy. Personality and Individual Differences, 115, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V., & Douglas, K. (2016). How “phubbing” becomes the norm: The antecedents and consequences of snubbing via smartphone. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V., & Douglas, K. (2018). The effects of “phubbing” on social interaction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(6), 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtright, J., & Caplan, S. (2020). A meta-analysis of mobile phone use and presence. Human Communication and Technology, 1(2), 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., Niu, Y., & Dong, Y. (2021). Exploring the relationship between narcissism and depression: The mediating roles of perceived social support and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G., Simpson, J., & Thomas, G. (2000). The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(3), 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. D., & Brunell, A. B. (2018). Narcissism and romantic relationships. In Handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 317–326). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frackowiak, M., Hilpert, P., & Russell, P. S. (2023). Impact of partner phubbing on negative emotions: A daily diary study of mitigating factors. Current Psychology, 43(2), 1835–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. A., Lerma, M., Perez, M. G., Medina, K. S., Rodriguez-Crespo, A., & Cooper, T. V. (2024). Psychosocial and personality traits associates of phubbing and being phubbed in Hispanic emerging adult college students. Current Psychology, 43(6), 5601–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geukes, K., Nestler, S., Hutteman, R., Dufner, M., Küfner, A. C. P., Egloff, B., Denissen, J. J. A., & Back, M. D. (2017). Puffed-up but shaky selves: State self-esteem level and variability in narcissists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A., MacLean, R., & Charles, K. (2021). Female narcissism: Assessment, aetiology, and behavioural manifestations. Psychological Reports, 125(6), 2833–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieve, R., Lang., C. P., & March, E. (2021). More than a preference for online social interaction: Vulnerable narcissism and phubbing. Personality and Individual Differences, 175, 110715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieve, R., & March, E. (2020). ‘Just checking’: Vulnerable and grandiose narcissism subtypes as predictors of phubbing. Mobile Media & Communication, 9(2), 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, J. L., Smith, T. W., Girard, J. M., & Wright, A. G. C. (2019). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: An interpersonal approach to construct validation. Journal of Personality Disorders, 33(6), 751–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D., & Katz, J. E. (2017). Texting’s consequences for romantic relationships: A cross-lagged analysis highlights its risks. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C. M., Hepper, E. G., & Sedikides, C. (2018). Understanding and mitigating narcissists’ low empathy. In Handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 335–343). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E., & Traupmann, J. (1981). Intimate relationships: A perspective from equity theory. Personal Relationships, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L., Miller-Ott, A., & Duran, R. (2017). Sports scores and intimate moments: An expectancy violations theory approach to partner cell phone behaviors in adult romantic relationships. Western Journal of Communication, 81(5), 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislev, E. (2023). The longitudinal effect of narcissistic admiration and rivalry traits on relationship satisfaction. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(7), 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komnik, L. A. (2024). What the phub?: A scoping review on partner phubbing and mental health in romantic relationships [Master’s dissertation, The University of Twente]. Available online: https://purl.utwente.nl/essays/101668 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Krasnova, H., Abramova, O., Notter, I., & Baumann, A. (2016, June 12–15). Why phubbing is toxic for your relationship: Understanding the role of smartphone jealousy among “Generation Y” users [Conference paper]. Twenty-Fourth European Conference in Information Systems (ECIS), Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R., Williams, J., & Lowe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Bizumic, B., Sivanathan, D., & Chen, J. (2023). Vulnerable and grandiose narcissism differentially predict phubbing via social anxiety and problematic social media use. Behavior and Information Technology, 43(12), 2930–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, H., Paisarnsrisomsuk, N., & Roberts, R. (2020). The effect of narcissistic admiration and rivalry on speaking performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B. T., & Coyne, S. (2016). “Technoference”: The interference of technology in couple relationships and implications for women’s personal and relational well-being. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(1), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B. T., & Drouin, M. (2019). Daily technology interruptions and emotional and relational well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B. T., Galovan, A., Cravens, J., & Drouin, M. (2018). “Technoference” and implications for mothers’ and fathers’ couple and coparenting relationship quality. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B. T., Galovan, A. M., & Drouin, M. (2020). Daily technoference, technology use during couple leisure time, and relationship quality. Media Psychology, 24, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B. T., & Wesselmann, E. (2021). “You phubbed me for that?” Reason given for phubbing and perceptions of interactional quality and exclusion. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(3), 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2010). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, S., & Schielzeth, H. (2012). A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4(2), 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, T. (2017). Attitude and emotional response among university students of Ankara towards Phubbing. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research, 6(11), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Peugh, J. (2010). A practical guide to multilevel modeling. Journal of School Psychology, 48(1), 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rentzsch, K., Wieczorek, L., & Gerlach, T. (2021). Situation perception mediates the link between narcissism and relationship satisfaction: Evidence from a daily diary study in romantic couples. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(7), 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. A., & David, M. E. (2016). My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R., Hendin, H., & Trzesniewski, K. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmann, E., Bierhoff, H. W., & Schmohr, M. (2010). Narcissism and perceived inequity in attractiveness in romantic relationships. European Psychologist, 16(4), 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schokkenbroek, J. M., Hardyns, W., & Ponnet, K. (2022). Phubbed and curious: The relation between partner phubbing and electronic partner surveillance. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C. (2021). In search of narcissus. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(1), 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, K. S., Shahnawaz., M. G., & Hasan, Z. (2024). Do narcissist phubs or get phubbed? Analyzing the role of motivational systems. The Journal of Psychology, 159(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, I., Salvati, M., & Enea, V. (2023). Sexual orientation and jealousy: A systematic review of the literature. Psicologia Sociale, 18(2), 179–216. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, T. T., Carnelley, K. B., & Hart, C. M. (2022). Phubbing in romantic relationships and retaliation: A daily diary study. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Abeele, M., Hendrickson, A., Pollmann, M., & Ling, R. (2019). Phubbing behavior in conversations and its relation to perceived conversation intimacy and distraction: An exploratory observation study. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Su, M., Ren, L., Xu, H., Lai, X., He, J., Du, M., Zhao, C., Zhang, G., & Yang, X. (2025). Partner phubbing and quality of romantic relationship in emerging adults: Testing the mediation role of perceived partner responsiveness and moderation role of received social support. BMC Psychology, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X., Xie, X., Wang, Y., Wang, P., & Lei, L. (2017). Partner phubbing and depression among married Chinese adults: The roles of relationship satisfaction and relationship length. Personality and Individual Differences, 110, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurst, S. N., Gerlach, T. M., Dufner, M., Rauthmann, J. F., Grosz, M. P., Küfner, A. C. P., Denissen, J. J. A., & Back, M. D. (2017). Narcissism and romantic relationships: The differential impact of narcissistic admiration and rivalry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(2), 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S., Lam, Z. K. W., Ma, Z., & Ng, T. K. (2016). Differential relations of narcissism and self-esteem to romantic relationships: The mediating role of perception discrepancy. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 19(4), 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler-Hill, V., Cosby, C., Vrabel, J., & Southard, A. (2020). Narcissism and mate retention behaviors: What strategies do narcissistic individuals use to maintain their romantic relationships? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(10–11), 2737–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler-Hill, V., Vrabel, J., McCabe, G., Cosby, C., Traeder, C., Hobbs, K., & Southard, A. (2018). Narcissism and the pursuit of status. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | |||||

| Perceived partner phubbing | 2.45 | 0.80 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.96 |

| Response: Curiosity | 3.12 | 2.40 | 0.87 | −0.52 | |

| Response: Resentment | 2.14 | 2.02 | 1.87 | 2.51 | |

| Response: Ignored | 5.84 | 2.71 | −0.50 | −1.07 | |

| Response: Conflict * | 1.40 | 1.22 | 2.50 | 6.37 | |

| Response: Retaliation | 4.64 | 2.65 | −0.06 | −1.34 | |

| Motivation for retaliation: Revenge | 1.95 | 1.67 | 1.71 | 1.77 | |

| Motivation for retaliation: Boredom | 5.43 | 1.97 | −0.69 | −0.24 | |

| Motivation for retaliation: Support * | 1.50 | 1.30 | 3.32 | 11.24 | |

| Motivation for retaliation: Approval * | 1.38 | 1.02 | 3.67 | 15.32 | |

| Relationship satisfaction | 5.70 | 1.25 | −1.10 | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| Anger/frustration | 1.72 | 0.84 | 1.51 | 2.20 | 0.98 |

| Self-esteem | 4.12 | 1.74 | −0.18 | −0.89 | |

| Anxious mood | 1.68 | 0.80 | 1.19 | 0.68 | 0.98 |

| Depressed mood | 1.64 | 0.78 | 1.23 | 0.87 | 0.98 |

| Level 2 | |||||

| Narcissistic rivalry | 2.29 | 1.03 | 1.19 | 1.47 | 0.85 |

| Narcissistic admiration | 3.64 | 1.23 | 0.40 | −0.06 | 0.86 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rivalry | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Admiration | 0.35 ** | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Phubbing | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Relationship satisfaction | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.24 ** | |||||||||||||

| 5. Self-esteem | 0.01 | 0.50 ** | −0.01 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| 6. Anxious mood | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.14 | −0.24 ** | −0.38 ** | |||||||||||

| 7. Depressive mood | 0.14 * | −0.18 * | 0.05 | −0.25 ** | −0.48 ** | 0.68 ** | ||||||||||

| 8. Anger/frustration | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.25 ** | −0.40 ** | −0.14 | 0.55 ** | 0.49 ** | |||||||||

| 9. Response: Curiosity | 0.24 ** | 0.00 | 0.27 ** | −0.04 | −0.15 * | 0.15 * | 0.12 | 0.15 * | ||||||||

| 10. Response: Resentment | 0.17 * | −0.07 | 0.49 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.18 * | 0.36 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.39 ** | |||||||

| 11. Response: Ignored | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.28 ** | ||||||

| 12. Response: Conflict | 0.17 * | 0.09 | 0.29 ** | −0.17 * | −0.01 | 0.16 * | 0.18 * | 0.31 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.18 * | |||||

| 13. Response: Retaliation | 0.15 * | −0.04 | 0.29 ** | −0.18 * | −0.20 ** | 0.15 * | 0.20 ** | 0.14 | 0.32 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.18 * | ||||

| 14. Revenge | 0.21 ** | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.37 ** | 0.00 | 0.18 * | 0.17 * | 0.28 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.50 ** | −0.18 * | 0.49 ** | 0.15 | |||

| 15. Boredom | 0.15 | −0.12 | 0.22 ** | −0.19 * | −0.27 ** | 0.16 | 0.32 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.04 | 0.25 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.33 ** | ||

| 16. Support | 0.23 ** | 0.08 | 0.19 * | −0.24 ** | 0.00 | 0.29 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.03 | 0.35 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.23 ** | |

| 17. Approval | 0.30 ** | 0.14 | 0.12 | −0.21* | 0.04 | 0.24 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.20 * | 0.39 ** | −0.09 | 0.45 ** | 0.20 * | 0.53 ** | 0.17 * | 0.76 ** |

| Relationship Satisfaction | Self-Esteem | Anxious Mood | Depressed Mood | Anger/Frustration | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p |

| Intercept | 5.82 | 5.65–5.98 | <0.001 | 4.07 | 3.87–4.26 | <0.001 | 1.64 | 1.55–1.73 | <0.001 | 1.56 | 1.47–1.66 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 1.56–1.74 | <0.001 |

| Partner Phubbing | −0.17 | −0.23–−0.11 | <0.001 | −0.06 | −0.13–0.01 | 0.109 | 0.07 | 0.03–0.11 | 0.002 | 0.05 | −0.01–0.09 | 0.018 | 0.16 | 0.11–0.22 | <0.001 |

| Narcissistic Rivalry | −0.15 | −0.31–0.01 | 0.075 | −0.31 | −0.38– −0.11 | 0.002 | 0.08 | −0.00–0.16 | 0.051 | 0.09 | 0.01–0.17 | 0.024 | 0.13 | 0.05–0.21 | 0.001 |

| Narcissistic Admiration | 0.23 | 0.09–0.37 | 0.001 | 0.82 | 0.66–0.99 | <0.001 | −0.08 | −0.15–−0.01 | 0.032 | −0.11 | −0.18–−0.04 | 0.001 | −0.09 | −0.15–−0.02 | 0.011 |

| Time | −0.01 | −0.03–0.01 | 0.349 | 0.01 | −0.01–0.03 | 0.199 | −0.02 | −0.03–−0.01 | 0.001 | −0.02 | −0.03–−0.00 | 0.009 | −0.01 | −0.03–−0.00 | 0.053 |

| Pphubbing*Narcissistic Rivalry | −0.03 | −0.09–0.04 | 0.459 | −0.05 | −0.13–0.02 | 0.165 | 0.01 | −0.04–0.06 | 0.725 | 0.02 | −0.03– 0.07 | 0.388 | 0.03 | −0.05–0.07 | 0.733 |

| Pphubbing*Narcissistic Admiration | −0.00 | −0.06–0.05 | 0.882 | −0.02 | −0.08–0.05 | 0.615 | 0.02 | −0.02–0.06 | 0.323 | 0.01 | −0.03–0.05 | 0.676 | 0.05 | −0.00–0.10 | 0.051 |

| Random Effects | |||||||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.37 | ||||||||||

| τ00 | 1.23ParticipantID | 1.69ParticipantID | 0.33ParticipantID | 0.36ParticipantID | 0.25ParticipantID | ||||||||||

| τ11 | 0.01ParticipantID.time | 0.01ParticipantID.time | 0.00ParticipantID.time | 0.00ParticipantID.time | 0.00ParticipantID.time | ||||||||||

| ρ01 | −0.04ParticipantID | 0.11ParticipantID | −0.32ParticipantID | −0.44ParticipantID | −0.18ParticipantID | ||||||||||

| ICC | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.41 | ||||||||||

| N | 210ParticipantID | 209ParticipantID | 210ParticipantID | 210ParticipantID | 210ParticipantID | ||||||||||

| Observations | 1514 | 1514 | 1517 | 1502 | 1512 | ||||||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.044/0.772 | 0.262/0.828 | 0.027/0.566 | 0.040/0.612 | 0.048/0.442 | ||||||||||

| Curiosity | Resentment | Ignored | Conflict | Retaliation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p |

| Intercept | 2.45 | 2.18–2.71 | <0.001 | 1.69 | 1.47–1.91 | <0.001 | 5.83 | 5.50–6.16 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.11–0.23 | <0.001 | 3.82 | 3.51–4.13 | <0.001 |

| Partner Phubbing | 1.21 | 1.06–1.36 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.88–1.12 | <0.001 | −0.39 | −0.64–−0.15 | 0.002 | 0.24 | 0.21–0.27 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 0.84–1.18 | <0.001 |

| Narcissistic Rivalry | 0.31 | 0.08–0.54 | 0.008 | 0.34 | 0.15–0.52 | <0.001 | −0.23 | −0.52–0.07 | 0.132 | 0.06 | 0.00–0.11 | 0.033 | 0.32 | 0.03–0.61 | 0.030 |

| Narcissistic Admiration | −0.05 | −0.25–0.15 | 0.635 | −0.08 | −0.24–0.08 | 0.342 | −0.06 | −0.31–0.20 | 0.664 | 0.02 | −0.03–0.06 | 0.437 | −0.05 | −0.30–0.20 | 0.686 |

| Time | −0.03 | −0.06–0.01 | 0.115 | 0.00 | −0.03–0.03 | 0.976 | −0.08 | −0.14–−0.02 | 0.011 | 0.00 | −0.00–0.01 | 0.254 | −0.13 | −0.18–−0.09 | <0.001 |

| Pphubbing*Narcissistic Rivalry | 0.19 | 0.02–0.35 | 0.026 | 0.09 | −0.04–0.22 | 0.158 | −0.13 | −0.41–0.14 | 0.347 | 0.02 | −0.01–0.06 | 0.171 | −0.03 | −0.22–0.17 | 0.780 |

| Pphubbing*Narcissistic Admiration | 0.04 | −0.11–0.18 | 0.633 | −0.09 | −0.21–0.03 | 0.130 | 0.13 | −0.11–0.37 | 0.295 | 0.04 | 0.01–0.07 | 0.008 | 0.04 | −0.13–0.21 | 0.638 |

| Random Effects | |||||||||||||||

| σ2 | 2.04 | 1.15 | 5.60 | 0.09 | 2.60 | ||||||||||

| τ00 | 2.58ParticipantID | 1.97ParticipantID | 2.63ParticipantID | 0.14ParticipantID | 3.67ParticipantID | ||||||||||

| τ11 | 0.01ParticipantID.time0 | 0.02ParticipantID.time0 | 0.04ParticipantID.time0 | 0.00ParticipantID.time0 | 0.03ParticipantID.time0 | ||||||||||

| ρ01 | −0.43ParticipantID | −0.50ParticipantID | 0.07ParticipantID | −0.46ParticipantID | −0.16ParticipantID | ||||||||||

| ICC | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.60 | ||||||||||

| N | 210ParticipantID | 209ParticipantID | 210ParticipantID | 210ParticipantID | 210ParticipantID | ||||||||||

| Observations | 1226 | 1223 | 1225 | 1224 | 1226 | ||||||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.126/0.588 | 0.138/0.644 | 0.018/0.404 | 0.109/0.628 | 0.088/0.635 | ||||||||||

| Revenge | Boredom | Need for Support | Need for Approval | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p |

| Intercept | 0.29 | 0.22–0.36 | <0.001 | 4.97 | 4.67–5.27 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.14–0.28 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.10–0.21 | <0.001 |

| Partner Phubbing | 0.19 | 0.14–0.25 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.34–0.73 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.02–0.11 | 0.004 | 0.09 | 0.05–0.13 | <0.001 |

| Narcissistic Rivalry | 0.10 | 0.03–0.17 | 0.005 | 0.20 | −0.07–0.48 | 0.143 | 0.09 | 0.03–0.15 | 0.004 | 0.13 | 0.08–0.18 | <0.001 |

| Narcissistic Admiration | 0.02 | −0.04–0.08 | 0.478 | −0.27 | −0.51–−0.02 | 0.031 | 0.03 | −0.02–0.08 | 0.233 | 0.02 | −0.03–0.06 | 0.447 |

| Time | −0.02 | −0.03–−0.01 | 0.001 | −0.09 | −0.14–−0.04 | 0.001 | −0.01 | −0.02–0.00 | 0.249 | −0.00 | −0.02–0.01 | 0.371 |

| Pphubbing*Narcissistic Rivalry | 0.03 | −0.03–0.09 | 0.276 | 0.08 | −0.15–0.30 | 0.507 | −0.02 | −0.07–0.03 | 0.428 | −0.02 | −0.07–0.02 | 0.284 |

| Pphubbing*Narcissistic Admiration | −0.02 | −0.08–0.04 | 0.466 | 0.13 | −0.09–0.35 | 0.239 | −0.00 | −0.06–0.05 | 0.809 | −0.00 | −0.05–0.04 | 0.903 |

| Random Effects | ||||||||||||

| σ2 | 0.14 | 1.86 | 0.11 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| τ00 | 0.15ParticipantID | 2.57ParticipantID | 0.11ParticipantID | 0.10ParticipantID | ||||||||

| τ11 | 0.03ParticipantID.time0 | 0.00ParticipantID.time0 | 0.00ParticipantID.time0 | |||||||||

| ρ01 | −0.21ParticipantID | −0.26ParticipantID | −0.35ParticipantID | |||||||||

| ICC | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.55 | ||||||||

| N | 185ParticipantID | 185ParticipantID | 184ParticipantID | 184ParticipantID | ||||||||

| Observations | 736 | 737 | 734 | 734 | ||||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.098/0.566 | 0.054/0.612 | 0.59/0.527 | 0.126/0.607 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hart, C.M.; Carnelley, K.B.; Vowels, L.M.; Thomas, T.T. Phubbed and Furious: Narcissists’ Responses to Perceived Partner Phubbing. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070853

Hart CM, Carnelley KB, Vowels LM, Thomas TT. Phubbed and Furious: Narcissists’ Responses to Perceived Partner Phubbing. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):853. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070853

Chicago/Turabian StyleHart, Claire M., Katherine B. Carnelley, Laura M. Vowels, and Tessa Thejas Thomas. 2025. "Phubbed and Furious: Narcissists’ Responses to Perceived Partner Phubbing" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070853

APA StyleHart, C. M., Carnelley, K. B., Vowels, L. M., & Thomas, T. T. (2025). Phubbed and Furious: Narcissists’ Responses to Perceived Partner Phubbing. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 853. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070853