When Politics Gets Personal: Students’ Conversational Strategies as Everyday Identity Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conversations Across the Aisle

1.2. Political Identities

1.2.1. Political Identities via Social Identity Theory

1.2.2. Political Identities via Self-Categorization Theory

1.2.3. Political Identities via Control Theory

1.2.4. Summary: Why Everyday Political Identity Matters

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment Strategy

2.3. Interviews and Data Collection

- “When was the last time you had a conversation with someone who does not share your political views? What was that conversation like?” (nature of conversation)

- “Where do you usually have these conversations? Are there any places where you find it easier to discuss political topics?” (context of conversation)

- “How did these conversations affect your views? Were there any lingering emotions? How has this experience shaped your willingness to engage in future political conversations?” (outcomes of conversation)

- “How do your friends and family talk about people with opposing political views? How does your ____ (name of network) perspective influence your willingness to engage with others?” (network dynamics)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

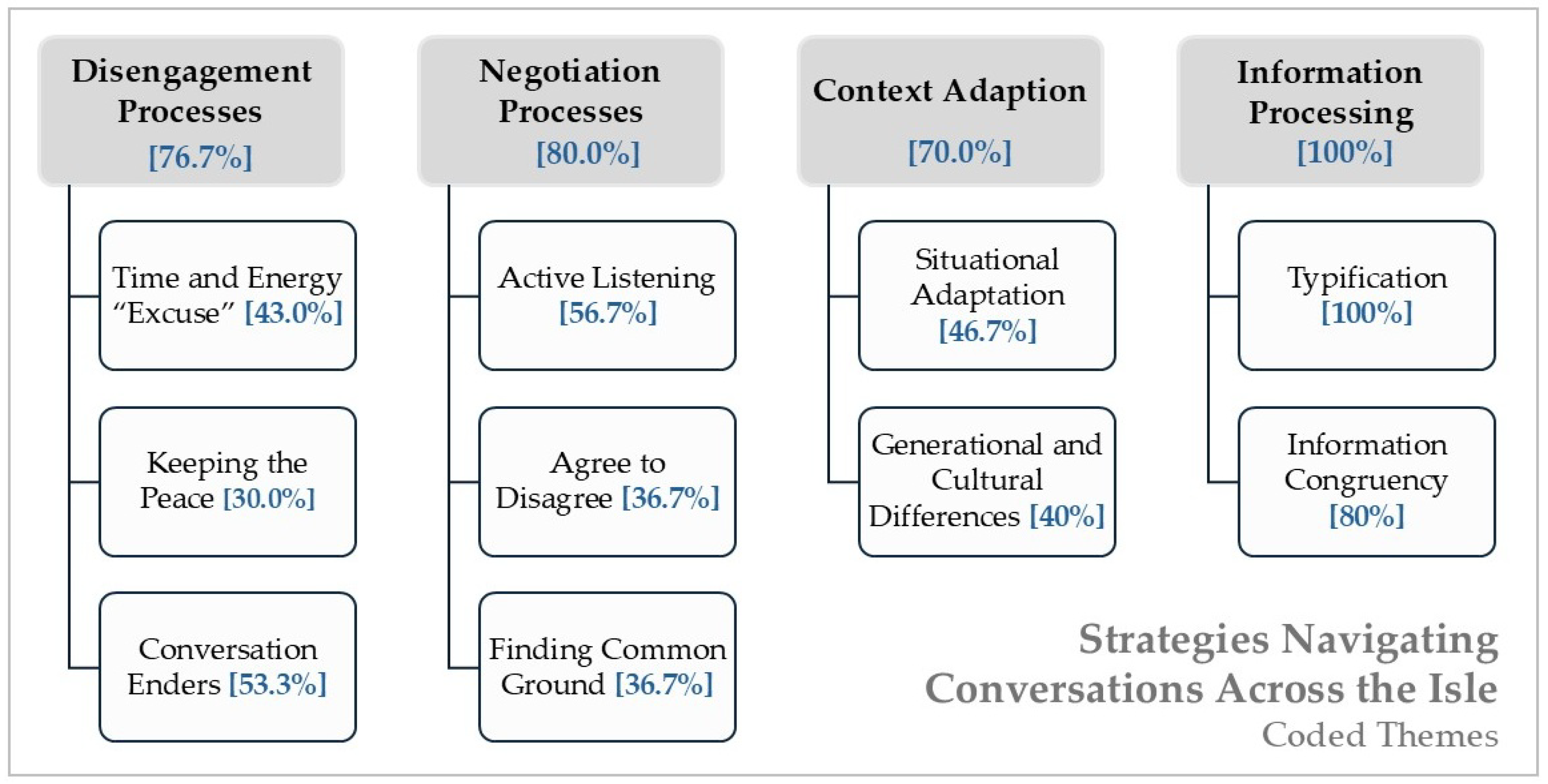

3.1. Disengagement Processes

3.1.1. Time and Energy “Excuse”

“I’m not going to waste my time arguing why trans people deserve rights when someone is clearly not going to change their mind.”—Rex (Male, 18)

“Well, in the past when I’ve tried, it just wasn’t worth the time and energy, and I don’t want to. I don’t even want to try to bring it up because they never seem to understand it from my point of view ever.”—Hazel (Female, 20)

3.1.2. Keeping-the-Peace

“It’s… one of the things right now [that] if I open that can of worms, I don’t know the outcome. I don’t know the possible relationships [at risk] … I [try] … not to express my opinions in those situations, like do I keep this environment neutral or do I kind of like sour it by disagreeing or … openly going against others’ beliefs.”—John (Male, 22)

“I don’t want to say it should happen, but like it should have happened [the storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021] … And my reasoning behind that is like our country was founded on kind of rebellious activities like that… So yeah, I tend to kind of keep that to myself.”—Rex (Male, 18)

3.1.3. Conversation Enders

“He’ll just kind of give[s] me this look, and I know it’s time to drop it. It’s like we’ve hit a wall, and I’m not getting anywhere.”—Grace (Female, 23)

“…slip in a comment here and there, but… keep [his] mouth shut and let them go”.—Taylor (Male, 22)

“I probably just kind of, ‘Oh, okay. Yeah, sure, I understand … [and then I say] ‘So this hot dog tastes nasty’ and just go from there.”—Levi (Male, 20)

3.2. Negotiation Processes

3.2.1. Active Listening

“I just I really try to keep reminding myself as I’m listening to think of it… through their perspective, but also to understand that they were raised that completely different way.”—Michael (Male, 20)

“But if you can sit down and have a truly educated conversation with someone on the other side of why they believe, what they believe … [and] how they think that’ll help the country or help the situation in the world. And that’s a productive conversation.”—Evan (Male, 24)

3.2.2. Agree-to-Disagree

“I’m just going to keep talking when I feel like I’m talking to you a brick wall now, you probably feel the exact same way right now …. We weren’t really, like, fully listening. We were just like continuing to reaffirm our position … obviously we weren’t yelling, but it kind of felt like… [so we decided to] ‘agree to disagree’ and … pat each other on the back and… walk out…”—Melissa (Female, 19)

“Yeah, I usually will say, like, let’s agree to disagree because it’s better than, you know, trying to push something on someone.”—Samual (Female, 18)

3.2.3. Finding Common Ground

“People are really divided…when it comes to conversation about [politics]… [conversations] with one of my other friends … sometimes … can be a little rough. But in the end, there’s always gonna be a mutual understanding about where we stand.”—Lucas (Male, 20)

“… whenever that happens… I go upstairs… do some breathing exercises… Then I go back downstairs. They [my parents] usually do the same thing… [then] we try to come to some sort of… ‘here’s where we agree’… and we kind of leave it at that.”—Melissa (Female, 20)

3.3. Context Adaptation

3.3.1. Situational Adaptation

“I feel like if you’re in public, there’s always going to be someone, whether they’re on the left or the right, if they don’t agree with you, … [they] are going to … be obnoxious about it. And it’s just something … I don’t need to deal with. So, it’s like, I’d rather not be in that situation.”—Evan (Male, 24)

“I think that work… it’s respectful to not have political arguments… I think that would be negative in a workplace setting.”—Kerri (Female, 21)

“I really don’t talk about political stuff that much openly unless it’s between, like, super close friends or family,”—Clarissa (Female, 19)

3.3.2. Generational, Cultural and Subcultural Differences

“LGBTQ issues are not something I’m willing to discuss with older people because they grew up in a different society, and it feels like a waste of time.”—Taylor (Male, 22)

“Older people just don’t understand why certain issues are important to us… they grew up in a different world, so they just don’t get it.”—Stephen (Male, 21)

“She’s from Mexico. But she looks [at] the way Trump has been treating and saying very disgusting things about pretty much her… it’s very emotional for her [to talk about these issues] because of the way she’s been treated here in America.”—Hannah (Female, 21)

3.4. Information Processing

3.4.1. Typification Processes

“[B]efore I say anything bad about Trump or whenever…I see some guy [wearing a] ‘Make America Great Again’ hat with the big pickup truck and a nice little, huge beard. [I decide ok], let’s avoid politics in all forms of fashion [with this person].”—Levi (Male, 20)

“They paint a picture of a bearded redneck and a trucker cap with an AR15 or for the college ones, a douche bag in a polo shirt with that hair that’s buzzed on the sides standing in the middle of campus shouting at people in the most obnoxious way of looking at it. On the other side, they paint like… the limp dick turtleneck wearing socialists who dye their hair a whole bunch of colors and identify as something absurd.”—Taylor (Male, 22)

“All my friends are like Democratic and they are going to end up bashing Republicans.”—Lucas (Male, 20)

“When I talk to my girlfriend’s grandparents and uncles… they’re super Republican and I just… I’m not comfortable talking about [politics] because I know they’re not going to agree with me in any way.”—Taylor (Male, 22)

3.4.2. Information Congruency

“People my age… they probably kind of just read from what they… identify themselves as… they read it and they believe it.”—Taylor (Male, 22)

“…rock [their] foundation and it makes [them] nervous…[because they] don’t want everything that [they’ve]…built [their] way of thinking [on] to…crumble.”—Ella (Female, 20)

“Yeah, and I think it’s because you had that confirmation. You know. No one is testing you if you’re right or wrong, it’s like, OK, this guy agrees with me, I must be right.”—Rex (Male, 18)

3.5. Summary: A Practical Inventory of Student Strategies3

4. Discussion

4.1. Priming Political Identities

4.1.1. Context Adaptation: Contextual Salience and Anticipatory Identity Management

4.1.2. Information Processing: Typification and Category Maintenance

4.1.3. Salience of Political Identities

4.2. Primed Political Identities

4.2.1. Avoidance Mechanisms

4.2.2. Modification Mechanisms

4.2.3. Reinforcement Mechanisms

4.3. The Bigger Picture

5. Conclusions

5.1. Identity Work Beneath Everyday Political Conversations

5.2. Learning to Live with Identity Discomfort

5.3. Rediscovering What Unites Us

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We thank an anonymous reviewer of an earlier version of this manuscript for encouraging us to more directly consider the larger political and epistemic context shaping these conversations. While our analysis remains focused on the lived experiences of students themselves, we acknowledge that broader societal dynamics—such as the rise of “post-truth” discourse and growing epistemic polarization—provide an important backdrop for understanding how these micro-level interactions unfold. We have expanded our introduction to briefly situate our study within this larger context. |

| 2 | We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer of an earlier draft for pushing us to more carefully align our claims with the actual scope of our data. In particular, their observation about the gap between our research questions, conceptual framing, and the empirical evidence we presented led us to revise both our theoretical framing and the tone of our claims. We have since refined our argument to acknowledge the cognitive emphasis of our findings, while recognizing the emotional undercurrents that—though unevenly expressed—were present in students’ accounts. This feedback ultimately helped us improve the clarity and coherence of our contribution, and we sincerely thank the reviewer for drawing our attention to this important issue. |

| 3 | We thank anonymous reviewer for encouraging us to strengthen the transition between our findings and their broader implications. This prompted us to step back, reflect more carefully on the patterns we observed, and clarify why they matter—improvements that, we believe, have made the paper stronger. |

| 4 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for pushing us to strengthen the narrative coherence of the manuscript by more clearly linking our research questions, findings, and theoretical interpretation. |

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Arao, B., & Clemens, K. (2013). From safe spaces to brave spaces: A new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice. In L. M. Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 135–150). Stylus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., & Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science, 26(10), 1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocian, K., Cichocka, A., & Wojciszke, B. (2021). Moral tribalism: Moral judgments of actions supporting ingroup interests depend on collective narcissism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 93, 104098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M., Judd, C. M., & Gliner, M. D. (1995). The effects of repeated expressions on attitude polarization during group discussions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(6), 1014–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, M. B. (1993). Social identity, distinctiveness, and in-group homogeneity. Social Cognition, 11(1), 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, E., & Cikara, M. (2017). Psychological barriers to reducing intergroup conflict: The role of moral superiority and dehumanization. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P. J. (2006). Identity change. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(1), 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P. J. (2016). Identity control theory. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The blackwell encyclopedia of sociology (pp. 1–5). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P. J., & Cerven, C. (2019). Identity accumulation, verification, and well-being. In J. E. Stets, & R. T. Serpe (Eds.), Identities in everyday life (pp. 17–33). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T., Foster, L., Sloan, L., & Bryman, A. (2021). Social research methods (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conover, P. J. (1988). The role of social groups in political thinking. British Journal of Political Science, 18(1), 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, P. J., Searing, D. D., & Crewe, I. M. (2002). The deliberative potential of political discussion. British Journal of Political Science, 32(1), 21–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S., & Berkel, L. (2022). Misperceptions of out-partisans’ democratic values may erode democratic norms. Scientific Reports, 12, 24200. [Google Scholar]

- Dessel, A., & Rogge, M. E. (2008). Evaluation of intergroup dialogue: A review of the empirical literature. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 26(2), 199–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eveland, W. P., & Hively, M. H. (2009). Political discussion frequency, network size, and ‘heterogeneity’ of discussion as predictors of political knowledge and participation. Journal of Communication, 59(2), 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N. T. (1994). Values, national identification, and favoritism toward the in-group. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 25(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N. T. (1995). Values, valences, and choice: The influence of values on the perceived attractiveness and choice of alternatives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(6), 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishkin, J. S., Siu, A., Diamond, L., & Luskin, R. C. (2020). Deliberative democracy and political polarization: Evidence from the America in One Room experiment. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B. Q., & Feinberg, M. (2020). Coping with politics: The benefits and costs of emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimer, J. A., & Skitka, L. J. (2020). The Montagu Principle: Incivility decreases politicians’ public approval, even with political allies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(5), 787–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhart, S., & Zhang, W. (2015). “Was it something I said?” “No, it was something you posted!” A study of the spiral of silence theory in social media contexts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(4), 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, E., Anduiza, E., & Rico, G. (2021). Affective polarization and the salience of elections. Electoral Studies, 69, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M. A. (2000). Subjective uncertainty reduction through self-categorization: A motivational theory of social identity processes. European Review of Social Psychology, 11(1), 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M. A. (2003). Social identity. In M. R. Leary, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 462–479). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M. A., & Abrams, D. (1988). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an Antiracist. One World. [Google Scholar]

- Levendusky, M. S. (2023). Our common bonds: Using identity to reduce partisan animosity. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2010). Using numbers in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S. C., Lawrence, R. G., & Cardona, A. (2017). Personalizing politics: How politicians’ personalized social media messages and social identity cues influence political participation and polarization. Journal of Communication, 67(6), 875–894. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, L. (2018). Post-truth. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz, D. C. (2002). The consequences of cross-cutting networks for political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 838–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D. G., & Bishop, G. D. (1970). Discussion effects on racial attitudes. Science, 169(3947), 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence a theory of public opinion. Journal of Communication, 24(2), 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S. L. (2022). American religion in the era of increasing polarization. Annual Review of Sociology, 48(1), 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. (2019). The public’s level of comfort talking politics and Trump. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/06/19/the-publics-level-of-comfort-talking-politics-and-trump/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ronning, R. (2004). The human library handbook. Stop the Violence. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2012). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ruckelshaus, J. (2022). What kind of identity is partisan identity? “Social” versus “political” partisanship in divided democracies. American Political Science Review, 116(4), 1477–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(3), 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J. E., & Tsushima, T. M. (2001). Negative emotion and coping responses within identity control theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 64(3), 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, N. J. (2010). Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 556–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhay, E. (2015). The politics of truth: How political beliefs and biases influence the acceptance of factual information. Political Psychology, 36(2), 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhay, E., Bello-Pardo, E., & Maurer, B. (2022). Why people avoid cross-cutting political conversations: Testing a dual-motivation framework. Political Behavior. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2012). Self-categorization theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 399–417). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. H. (2005). Peter J. Burke’s identity control theory. In J. E. Stets (Ed.), The sociology of emotions (pp. 124–133). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, K. C. (2004). Talking about politics: Informal groups and social identity in American life. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, C., Cramer, K. J., Wagner, M. W., Alvarez, G., Friedland, L. A., Shah, D. V., & Franklin, C. (2017). When we stop talking politics: The maintenance and closing of conversation in contentious times. Journal of Communication, 67(1), 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A., & Giles, H. (1996). Intergenerational conversations: Young adults’ retrospective accounts. Human Communication Research, 23(2), 220–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, X., Nagda, B. A., Chesler, M., & Cytron-Walker, A. (2007). Intergroup dialogue in higher education: Meaningful learning about social justice. ASHE Higher Education Report, 32(4), 1–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Pseudonym | Politics | Gender | Age | Race | I-Time * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ashley | conservative | female | 20 | Caucasian | 66:47 mins |

| 2 | Ella | conservative | female | 20 | Caucasian | 54:52 mins |

| 3 | Tiffany | conservative | female | 19 | Caucasian | 75:05 mins |

| 4 | Clarissa | conservative | female | 19 | Caucasian | 50:46 mins |

| 5 | Kerri | conservative | female | 18 | Caucasian | 39:03 mins |

| 6 | Evan | conservative | male | 24 | Caucasian | 63:12 mins |

| 7 | Edward | conservative | male | ** | Caucasian | 25:50 mins |

| 8 | Nick | conservative | male | 19 | Caucasian | 55:50 mins |

| 9 | Rex | conservative | male | 18 | Caucasian | 53:45 mins |

| 10 | Zack | conservative | male | 21 | Caucasian | 55:24 mins |

| 11 | Taylor | liberal | male | 22 | Caucasian | 74:25 mins |

| 12 | Brittany | liberal | female | 18 | African American | 73:56 mins |

| 13 | Tammy | liberal | female | 21 | Multiracial | 67:29 mins |

| 14 | Louise | liberal | female | 22 | Caucasian | 62:59 mins |

| 15 | Alyssa | liberal | female | 19 | Hispanic/Latino | 68:08 mins |

| 16 | Hazel | liberal | female | 20 | African American | 37:00 mins |

| 17 | Stephen | liberal | male | 21 | Hispanic/Latino | 52:15 mins |

| 18 | Levi | liberal | male | 20 | African American | 86:24 mins |

| 19 | Mark | liberal | male | 22 | Caucasian | 73:31 mins |

| 20 | Tony | liberal | male | 22 | Caucasian | 33:19 mins |

| 21 | Grace | other | female | 23 | Caucasian | 59:52 mins |

| 22 | Patrice | other | female | 19 | Caucasian | 49:37 mins |

| 23 | Melissa | other | female | 20 | Caucasian | 65:57 mins |

| 24 | Samantha | other | female | 18 | Caucasian | 55:06 mins |

| 25 | Andrew | other | male | 24 | Hispanic/Latino | 43:49 mins |

| 26 | Lucas | other | male | 20 | Hispanic/Latino | 48:23 mins |

| 27 | John | other | male | 22 | Caucasian | 66:16 mins |

| 28 | Samuel | other | male | 18 | Caucasian | 78:55 mins |

| 29 | Michael | other | male | 20 | Caucasian | 39:53 mins |

| 30 | Hannah | other | female | 21 | Hispanic/Latino | 54:46 mins |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zschau, T.; Lee, H.; Miller, J. When Politics Gets Personal: Students’ Conversational Strategies as Everyday Identity Work. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060835

Zschau T, Lee H, Miller J. When Politics Gets Personal: Students’ Conversational Strategies as Everyday Identity Work. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060835

Chicago/Turabian StyleZschau, Toralf (Tony), Hosuk Lee, and Jason Miller. 2025. "When Politics Gets Personal: Students’ Conversational Strategies as Everyday Identity Work" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060835

APA StyleZschau, T., Lee, H., & Miller, J. (2025). When Politics Gets Personal: Students’ Conversational Strategies as Everyday Identity Work. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060835