Loss and Grief Among Bereaved Family Members During COVID-19 in Brazil: A Grounded Theory Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Context and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Rigor and Reflexivity

2.6. Ethics

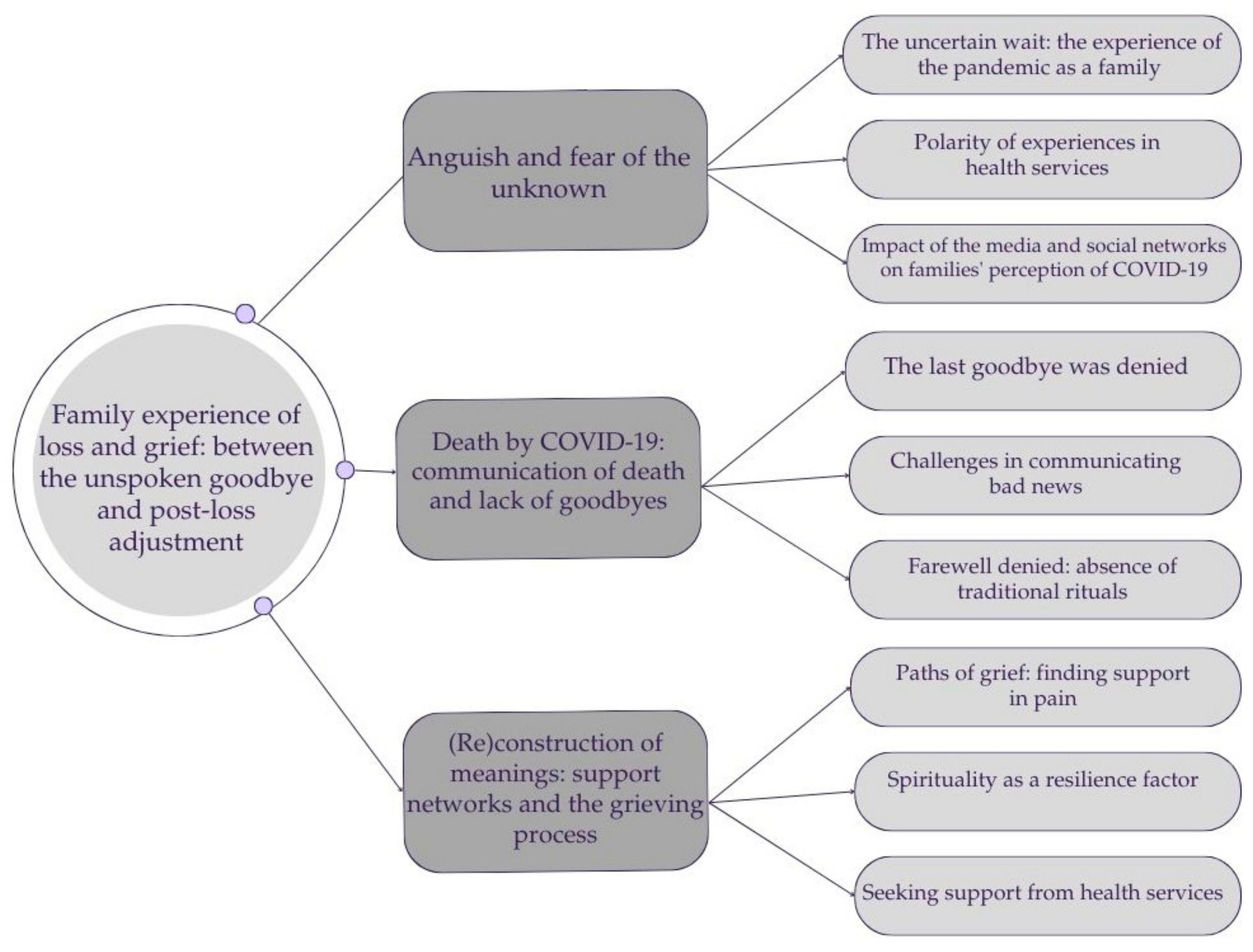

3. Results

3.1. Participants Background

3.2. Interview Findings

3.2.1. Anguish and Fear of the Unknown

[…] For me, COVID-19 had a huge impact. I quit my job, gave up my apartment, a radical change […] all because of COVID-19. I stopped working and stayed at my father’s house taking care of him because he had become infected. I had very difficult days because there was no way for him to receive the medical care he needed.(P9, 54 years old)

[…] He was isolated in a room, in a bathroom, and I stayed in the other rooms of the house with our dogs. I wore gloves, a mask, alcohol gel, separated his cutlery from mine, and when I took them out I had to wash them separately. He also took great care to ensure that I didn’t touch him, so as not to get infected.(P18, 46 years old)

[…] We were scared, yes. When the infection appeared, we started monitoring my father and uncle’s saturation, and the values were always low. We realized that keeping them at home was no longer possible. It was a difficult decision, because the hospitals were full.(P20, 28 years old)

[…] My wife, 36 years together, and she passed away from COVID-19. In fact, I caught COVID and I was the one who passed it on to her.(P2, 59 years old)

[…] COVID was very hard on my family. My mother has COPD and was the first to become infected. My father, because he was worried about her, took care of her. However, as he had heart problems and diabetes, he ended up catching the infection and ended up dying. Sometimes I think that I should have been more careful and not let him take care of my mother.(P20, 28 years old)

[…] It was very quick, he felt ill and went to look for a basic health unit. Meanwhile, he left by ambulance for the hospital […] it all happened very quickly. It was not possible to prepare anything.(F21, 43 years old)

[…] The people who helped us best were the nurses and physiotherapists, these people provided good care, were well prepared. Days after my mother passed away, I went to the hospital and took a basket to the staff as a sign of gratitude. They were doing their best there, without a doubt.(P16, 36 years old)

[…] She [sister] was very well looked after, because every day they came to see her, everyone helped, someone always gave support and cheered for her.(P12, 41 years old)

[…] Everyone blames doctors, not me, I praise them. And I think people have to stop with this ignorance, they did everything they could to save people, including risking their own lives.(F18, 46 years old)

[…] They were the most difficult and darkest days of my life, because we even fought for a private ICU. If that were the case, I would sell what I had to save his [husband’s] life, but there was no vacancy. I know what I’m going to say is strong, but they had to choose who would live and who would die.(P18, 46 years old)

[…] At the time, there was no ICU available, he [brother] stayed in the hospital and got better. However, the disease ended up affecting the lungs, kidneys and other organs. If he had the care he needed, perhaps he wouldn’t have died.(P14, 55 years old)

[…] They set up makeshift ICUs. There was always someone with the curtain closed, someone who had passed away and was waiting for their family, I ended up witnessing all that suffering of the families.(P21, 43 years old)

[…] She [wife] stayed at home, well we both had COVID-19, but she was much worse than me, she had trouble breathing and didn’t feel well. And then the news on TV drove us crazy… there was a lot of misleading news, I remember seeing a news story that recommended taking ivermectin. I almost ruined my health by having to take this medicine. Wow, it was horrible, right? But the worst, the worst was the media.(P2, 59 years old)

[…] It was very difficult. On television, the president joked that he was not a gravedigger, he imitated COVID-19 patients, that monster. There is no greater pain in the world than losing someone unjustly. What happened in Brazil and in the world, but in Brazil specifically, is collective murder.(P18, 46 years old)

Although the news was not the best, television warned people to be cautious. We saw the news about the mortality associated with COVID-19 and we ended up not leaving the house to protect ourselves.(P18, 46 years old)

I redoubled my care with the use of a mask and hygiene to protect those I loved.(P13, 32 years old)

3.2.2. Death by COVID-19: Communication of Death and Lack of Goodbyes

[…] They only let me and my brother go there to visit, just once. She [mother] was unconscious and intubated. For us it was a farewell, because the following morning she passed away. My other relatives didn’t have the opportunity to say goodbye.(P16, 36 years old)

[…] When she [sister] went there, it was the worst thing, because we didn’t see her anymore and we couldn’t even talk on the phone. That was the worst part, if I had known that those were her last days, I would have left her at home to die with her family.(P12, 41 years old)

[…] We went to the ICU and only saw her through the glass [mother]. We couldn’t talk to her, and there we said a prayer, we said goodbye to her, because we knew she was really going. And that night she died.(P17, 59 years old)

[…] It was very important because I recorded audios, they took his [husband’s] hand, passed on the audios of our godchildren, who are like children to us, and he got very emotional.(P18, 46 years old)

[…] At first, my mother used WhatsApp to send us photos, with the mask on, but when it was time to remove the oxygen, I was very short of breath. Then, when it got worse, the nurses made the call, because she was already intubated.(P16, 36 years old)

[…] They called me the next morning when my brother and I went to visit, they just said that my mother had passed away. To this day I still don’t believe it, because during the visit no one warned us that the situation was very serious and that there was a risk of death. We were not prepared for what happened.(F16, 36 years old)

[…] The professional called my mother at one twenty in the morning and said that my brother had just died. Luckily, she wasn’t alone. But receiving news like that, without preparation, brought her to her knees. I had asked the nurse on duty to call me.(F14, 55 years old)

[…] She [sister] was there (in the hospital) and we were here isolated. When this bad news came, I knew she had been hospitalized, but when she got worse, I didn’t know, because for me she was fine and suddenly she wasn’t fine anymore. My God, I miss her so much, I miss her so much. I still feel her with me….(F1, 50 years old)

[…] There were no goodbyes, we couldn’t say goodbye, there was nothing… It was just a black bag. At that time, no one buried anyone, we couldn’t hold wakes, we couldn’t do anything. To this day I blame myself for this.(P1, 50 years old)

[…] The coffin was sealed, we didn’t see him, we don’t know if it was him [husband]. I sent clothes, but they said they didn’t need clothes and threw them away, that time was the worst… How could we say goodbye if we didn’t see him. I still think it might not have been him…(P3, 78 years old)

[…] On the day of the funeral, my mother and I were in the car. I had symptoms, and my mother had COVID. It was very difficult, and it left us with scars. My father simply left home on Sunday, and my mother says that it feels like he left, that he abandoned us. A horrible feeling, because you are with the person here, the person leaves and never comes back.(P9, 55 years old)

[…] When my mother passed away, they all came with her in the funeral car. They had barely lowered the window when they said, “You are Mrs. Catarina’s relatives.” We said, “Yes,” and they said, “Then get in.” When we arrived at the grave, there was a tape, like when someone is murdered, they put tape around it, so people wouldn’t get too close. We were so focused on that, that they then put her inside, covered it, and left. When I looked around, there was no one else there. I said, we forgot to say a farewell prayer, it was very shocking.(P17, 59 years old)

[…] The most that could be done was a car parade in a funeral procession, which brought together some family members, each in their own car.(F13, 32 years old)

[…] Since his family couldn’t come, we did a video call broadcast on Instagram so the family could watch. My oldest son didn’t want to go, so he stayed at home with my mother. She said that he attended the funeral and kept pressing the little heart, the white heart on the live stream kept rising.(F21, 43 years old)

3.2.3. (Re)Construction of Meanings: Support Networks and the Grieving Process

[…] If I didn’t have my friends, if I didn’t, I would really want to throw myself in front of a train. I spent about six months where nothing mattered to me, nothing. […] My friends gave me a lot of support. Wow, I have a friend here who would travel to come see me, to see how I was doing, he would call me every day. If it weren’t for my friends, I don’t know where I would be, what would become of me now.(P2, 59 years old)

[…] Grief is eternal, we just get used to the pain and that’s why support from others is important. There were a lot of people who were left alone, that’s much worse(P4, 55 years old)

[…] I would call my mother to tell her about everything good that happened in my life. Even today, whenever something happens, I say, I have to call my mother, then I remember that she’s not here anymore, but then I look at the photographs and it helps me.(P17, 59 years old)

[…] We talked, we laughed, we worked, she helped me here at home. It was little, but she helped me, I miss her. I remember with joy when we would have coffee together, drink chimarrão [tea] and I feel that she is close to me.(P10, 68 years old)

[…] Despite all the horror, all the difficulties, God helps me.(P21, 43 years old)

[…] We do what God asks of us, we all have a purpose. God takes care of me and this helps me find the strength to take care of others.(P19, 68 years old)

[…] I think this way, that God knows what he does, it was his time. COVID-19 was just the circumstance. So, we have to think this way, otherwise we suffer too much.(P9, 50 years old)

[…] I went to the health center and asked the doctor if there was a psychiatrist or psychologist who could help me. She said she there was none, and didn’t know if there would be.(P20, 28 years old)

[…] They didn’t offer support, nothing, everyone is left in the dark.(P17, 59 years old)

[…] No support, no one in the hospital, no one, nothing. You were the only one to call me. We had nothing, not a word, nothing.(P10, 68 years old)

[…] I think there was a lack of support from the government and there was a lot of fuss. Anyway, it was missing. I think the Unified Health Service [SUS] is great, but there was a lack of good service, but we understand that there was a pandemic. In fact, there was only you, only you who came to talk to me about COVID-19, that’s why I made a point of talking to you, what you’re doing is very important.(P2, 59 years old)

[…] I had support from Unimed (Health Plan), social assistance, psychologist, everything. Unimed is very well supported. The psychologist, when he passed away, came to see me, she prepared me a lot, it was very important to have talked to her.(P7, 65 years old)

[…] When my mother passed away, the hospital had a psychologist, and I was asked if I, my brother or my father needed any support and that ended up happening.(P16, 36 years old)

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Araújo, J. I., & Júnior, G. A. (2023). Bereaved families: The process of elaborating grief as a result of death from COVID-19. Scientia Generalis, 4(2), 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, Z., Naghavi, A., & Abedi, M. R. (2022). Beyond a traumatic loss: The experiences of mourning alone after parental death during COVID-19 pandemic. Death Studies, 46(1), 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, T. D., Melo, M. S. S., & Menezes, D. A. (2022). Analysis of family grief in the context of COVID-19: An integrative review. Research, Society and Development, 11(12), e545111234675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M. D. S., Marques, F. R. D. M., Gallo, A. M., Garcia-Vivar, C., Carreira, L., & Salci, M. A. (2023). Striking a new balance: A qualitative study of how family life has been affected by COVID-19. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 31, e4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros-Lane, L., Germany, A., Smith, P., & Stovall, T. (2024). A socioecological examination of the challenges associated with young widowhood: A systematic review. Omega, 302228241227996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalani, G., Azzola, C., Sassu, R., Marogna, C., & Testoni, I. (2022). Spirituality for coping with the trauma of a loved one’s death during the COVID-19 pandemic: An Italian qualitative study. Pastoral Psychology, 71(2), 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, A. J. (2023). From data management to actionable findings: A five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J., Waring, G., Turner, M., Currell, K., & Caress, A. L. (2023). Exploring the impact of bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic on children and young people: A scoping review. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 47(1), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, M. L. M., & Alves, E. D. (2023). Social distancing in urban contexts in the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges for the field of mental health. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva, 33, e33007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, L. J., Mancini, V. O., Lee, S. A., Pappalardo, E. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2022). Risk factors for dysfunctional grief and functional impairment for all causes of death during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of meaning. Death Studies, 46(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buus, N., & Perron, A. (2020). The quality of quality criteria: Replicating the development of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). International Journal of Nursing Studies, 102, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canuto, R. M. S., Ferreira, A. C. L., Novaes, L. F., & Salles, R. J. (2023). The grieving process in relatives of COVID-19 victims. Studies and Research in Psychology, 23(2), 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J., Gunda, A., Qasim, K., Allen, R., Bradley, M., & Prescott, J. (2023). Losing a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic: An on-line survey looking at the effects on traumatic stress, coping and post-traumatic growth. Omega, 88(2), 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis (2nd ed.). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2017). Constructivist grounded theory. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K., & Thornberg, R. (2020). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. (2020). Social support as a protective factor against the effect of grief reactions on depression for bereaved single older adults. Death Studies, 46(3), 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherblanc, J., Côté, I., Mercure, C., Boever, C., & Zech, E. (2025). Rituals in grief: Why meaning matters more than numbers. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V. J., Martínez-González, M. B., Benitez-Agudelo, J. C., Navarro-Jiménez, E., Beltran-Velasco, A. I., Ruisoto, P., Diaz Arroyo, E., Laborde-Cárdenas, C. C., & Tornero-Aguilera, J. F. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental disorders. A critical review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cost, K. T., Crosbie, J., Anagnostou, E., Birken, C. S., Charach, A., Monga, S., Kelley, E., Nicolson, R., Maguire, J. L., Burton, C. L., Schachar, R. J., Arnold, P. D., & Korczak, D. J. (2021). Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(4), 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costeira, C., Dixe, M. A., Querido, A., Rocha, A., Vitorino, J., Santos, C., & Laranjeira, C. (2024). Death unpreparedness due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A concept analysis. Healthcare, 12(2), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M., Simões, G., Soares, J., & Santos, E. (2023). Grief and coping in family members and significant others of people who died from COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Referência, 6(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dado, M., Spence, J. R., & Elliot, J. (2023). The case of contradictions: How prolonged engagement, reflexive journaling, and observations can contradict qualitative methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, C. d. R., Azevedo, R. C. S. d., Vieira, L. C., Côrtes, M. T. F., Federmann, A. L. P., Cucco, L. d. M., Rodrigues, L. R., Domingues, J. F. R., Dantas, J. E., Portella, I. P., & Cassorla, R. M. S. (2020). Grief in times of COVID-19: Challenges of care during the pandemic. Latin American Journal of Fundamental Psychopathology, 23(3), 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, B., Vanstone, M., Swinton, M., Brandt Vegas, D., Dionne, J. C., Cheung, A., Clarke, F. J., Hoad, N., Boyle, A., Huynh, J., Toledo, F., Soth, M., Neville, T. H., Fiest, K., & Cook, D. J. (2022). Sacrifice and solidarity: A qualitative study of family experiences of death and grief in intensive care settings during the pandemic. BMJ Open, 12, e058768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diolaiuti, F., Marazziti, D., Beatino, M. F., Mucci, F., & Pozza, A. (2021). Impact and consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on complicated grief and persistent complex bereavement disorder. Psychiatry Research, 300, 113916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisma, M. C., & Tamminga, A. (2022). COVID-19, natural, and unnatural bereavement: Comprehensive comparisons of loss circumstances and grief severity. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2062998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisma, M. C., Tamminga, A., Smid, G. E., & Boelen, P. A. (2021). Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: An empirical comparison. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrela, F. M., Silva, A. F., Oliveira, A. C. B., Magalhães, J. R. F., Soares, C. F. S., Peixoto, T. M., & Oliveira, M. A. S. (2021). Coping with mourning for family loss due to COVID-19: Short and long-term strategies. Persona y Bioética, 25(1), e2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, S., Smith, D., Griffin, H., Shreve, S. T., Kinder, D., Kutney-Lee, A., & Ersek, M. (2021). “Why couldn’t I go in to see him?” Bereaved families’ perceptions of end-of-life communication during COVID-19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(3), 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Ó., & González-González, M. (2022). The dead with no wake, grieving with no closure: Illness and death in the days of coronavirus in Spain. Journal of Religion and Health, 61, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife, S. T., & Gossner, J. D. (2024). Deductive qualitative analysis: Evaluating, expanding, and refining theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, R., Gheorghita Puscaselu, R., Anchidin-Norocel, L., Dimian, M., & Savage, W. K. (2022). Global challenges to public health Care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of pandemic measures and problems. Journal of personalized medicine, 12(8), 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firouzkouhi, M., Alimohammadi, N., Abdollahimohammad, A., Bagheri, G., & Farzi, J. (2023). Bereaved families views on the death of loved ones due to COVID 19: An integrative review. Omega, 88(1), 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, J. A., Hakim, A., Victory, K. R., Date, K., Lynch, M., Dahl, B., Henao, O., & CDC COVID-19 Response Team. (2021). Mitigation policies and COVID-19-associated mortality—37 European countries, January 23–June 30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(2), 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadagnoto, T. C., Mendes, L. M. C., Monteiro, J. C. d. S., Gomes-Sponholz, F. A., & Barbosa, N. G. (2022). Emotional consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents: Challenges to public health. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 56, e20210424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesi, C., Carmassi, C., Cerveri, G., Carpita, B., Cremone, I. M., & Dell’Osso, L. (2020). Complicated grief: What to expect after the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamattey, M. E. P., Frutuoso, J. T., Bellaguarda, M. L. d. R., & Luna, I. J. (2021). Funeral rituals in the COVID-19 pandemic and mourning: Possible reverberations. Anna Nery School, 26, e20210208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardon-Perlini, N. M. O., Simon, B. S., & Lacerda, M. R. (2020). Grounded theory methodological aspects in Brazilian nursing thesis. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(6), e20190274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R. M., & Moreira, M. R. (2022). How does the context effect of denialism reinforce the oppression of the vulnerable people and negatively determine health? Lancet Regional Health. Americas, 12, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, E., Goss, S., Longo, M., Seddon, K., Torrens-Burton, A., Sutton, E., Farnell, D. J., Penny, A., Nelson, A., Byrne, A., & Selman, L. E. (2022). Parental perspectives on the grief and support needs of children and young people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative findings from a national survey. BMC Palliative Care, 21(1), 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, E., Medeiros Mirra, R., Goss, S., Longo, M., Byrne, A., Farnell, D. J. J., Seddon, K., Penny, A., Machin, L., Sivell, S., & Selman, L. E. (2023). Prolonged grief during and beyond the pandemic: Factors associated with levels of grief in a four time-point longitudinal survey of people bereaved in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1215881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Fernández, C., & Meneses-Falcón, C. (2021). I can’t believe they are dead. Death and mourning in the absence of goodbyes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(4), e1220–e1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkson, G. M., Huggins, C. L., & Doyle, M. (2024). Transnational caregiving and grief: An autobiographical case study of loss and love during the COVID-19 pandemic. Omega, 90(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iserson, K. V. (2020). Healthcare ethics during a pandemic. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(3), 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins University. (2023). COVID-19 dashboard. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Fernández-Alcántara, M., & Cénat, J. M. (2020). Prolonged grief related to COVID-19 deaths: Do we have to fear a steep rise in traumatic and disenfranchised griefs? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S94–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. M. (2021). The many faces of grief: A systematic literature review of grief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 31(1), 105413732110380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lana, R. M., Coelho, F. C., Gomes, M. F. d. C., Cruz, O. G., Bastos, L. S., Villela, D. A. M., & Codeço, C. T. (2020). Emergence of the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the role of timely and effective national health surveillance. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(3), e00019620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., Moura, D., Marcon, S., Jaques, A., Salci, M. A., Carreira, L., Cuman, R., & Querido, A. (2022a). Family bereavement care interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 12(4), e057767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., Moura, D., Salci, M. A., Carreira, L., Covre, E., Jaques, A., Cuman, R. N., Marcon, S., & Querido, A. (2022b). A scoping review of interventions for family bereavement care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., & Querido, A. (2021). Changing rituals and practices surrounding COVID-19 related deaths: Implications for mental health nursing. British Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C., & Querido, A. (2023). An in-depth introduction to arts-based spiritual healthcare: Creatively seeking and expressing purpose and meaning. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1132584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarova, M., Caligiuri, P., Collings, D. G., & De Cieri, H. (2023). Global work in a rapidly changing world: Implications for MNEs and individuals. Journal of World Business, 58, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N., Becker, T. D., & Rice, T. (2022). Preparing for the COVID-19 paediatric mental health crisis: A focus on youth reactions to caretaker death. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(1), 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena, P. L. C., Alves, A. M. P. d. M., Batista, P. S. d. S., Agra, G., Lordão, A. V., & Costa, S. F. G. d. (2024). End-of-life care and grief: A study with family members of COVID-19 victims. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 29, e02602024. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, T. M., Tofthagen, C. S., & Buck, H. G. (2020). Complicated grief: Risk factors, protective factors, and interventions. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 16(2), 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, M. J., Simões, L., Ali, A. M., & Laranjeira, C. (2024). Family experiences of loss and bereavement in palliative care units during the COVID-19 pandemic: An interpretative phenomenological study. Healthcare, 12(17), 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V., & Padhy, S. K. (2020). Ethical dilemmas faced by health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic: Issues, implications and suggestions. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J., Arruda, G., Melo, C. d. F., & Martins, C. (2024). Real and symbolic grief experiences during COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative literature review: A. Portuguese Journal of Behavioral and Social Research, 10(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S. S., Shahbazi, N., Taban, M., Alimohammadi, A., & Shati, M. (2023). Mourning during corona: A phenomenological study of grief experience among close relatives during COVID-19 pandemics. Omega, 87(4), 1088–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R. (2023). Meaning versus sense: A proposal for a conceptual distinction to studies on grief. Studies and Research in Psychology, 23(3), 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2019). Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Studies, 43(2), 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R. A., Baldwin, S. A., & Gillies, J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R. A., Klass, D., & Dennis, M. R. (2014). A social constructionist account of grief: Loss and the narration of meaning. Death Studies, 38(6–10), 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R. A., & Lee, S. A. (2022). Circumstances of the death and associated risk factors for severity and impairment of COVID-19 grief. Death Studies, 46(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, H., & Mitchell, G. (2016). What is grounded theory? Evidence-Based Nursing, 19, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufadewa, I. I., Adesina, M. A., Oladokun, B., Baru, A., Oladele, R. I., Iyanda, T. O., & Abudu, F. (2020). “I was scared i might die alone”: A qualitative study on the physiological and psychological experience of COVID-19 survivors and the quality of care received at health facilities. International Journal of Travel Medicine and Global Health, 8(2), 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyase, A. O., Hocaoglu, M., Cripps, R. L., Maddocks, M., Walshe, C., Fraser, L. K., Preston, N., Dunleavy, L., Bradshaw, A., Murtagh, F. E. M., Bajwah, S., Sleeman, K. E., Higginson, I. J., & CovPall study team. (2021). The challenges of caring for people dying from COVID-19: A multinational, observational study of palliative and hospice services (CovPall). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(3), 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. H. P. (2020). “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 42(3), 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osofsky, J. D., Osofsky, H. J., & Mamon, L. Y. (2020). Psychological and social impact of COVID-19. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(5), 468–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, D. K. (2017). Qualitative methods in social work research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, B., Strupp, J., Schloesser, K., Voltz, R., Jung, N., Leisse, C., Bausewein, C., Pralong, A., & Simon, S. T. (2022). It’s like standing in front of a prison fence—Dying during the SARS-CoV2 pandemic: A qualitative study of bereaved relatives’ experiences. Palliative Medicine, 36(4), 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenta, S., & Capelas, M. (2020). Intervention in the grief process in Portugal by palliative care teams. Cadernos De Saúde, 12(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rädiker, S., & Kuckartz, U. (2019). Analyse qualitativer daten mit MAXQDA. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, R. (2020). A reflection on racial injustice and (black) anticipatory grief compounded by COVID-19. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 3(2), 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D., Karim, S. S. A., Aknin, L., Allen, J., Brosbøl, K., Colombo, F., Barron, G. C., Espinosa, M. F., Gaspar, V., Gaviria, A., Haines, A., Hotez, P. J., Koundouri, P., Bascuñán, F. L., Lee, J. K., Pate, M. A., Ramos, G., Reddy, K. S., Serageldin, I., … Michie, S. (2022). The lancet commission on lessons for the future from the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet, 400(10359), 1224–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. L. G. D., Cunha, K. S., Adamy, E. K., Backes, M. T. S., Leite, J. L., & Sousa, F. G. M. (2018). Data analysis: Comparison between the different methodological perspectives of the Grounded Theory. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 52, e03303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, R., Roknuzzaman, A. S. M., Hossain, M. J., Bhuiyan, M. A., & Islam, M. R. (2023). The WHO declares COVID-19 is no longer a public health emergency of international concern: Benefits, challenges, and necessary precautions to come back to normal life. International Journal of Surgery, 109(9), 2851–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B., Crepaldi, M. A., Bolze, S. D. A., Neiva-Silva, L., & Demenech, L. M. (2020). Mental health and psychological interventions during the new coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37, e200063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoo, C., Azhar, Y., Mughal, S., & Rout, P. (2025). Grief and prolonged grief disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507832/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Selman, L. E., Farnell, D., Longo, M., Goss, S., Seddon, K., Torrens-Burton, A., Mayland, C. R., Wakefield, D., Johnston, B., Byrnem, A., & Harrop, E. (2022). Risk factors associated with poorer experiences of end-of-life care and challenges in early bereavement: Results of a national online survey of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative Medicine, 36(4), 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahini, N., Abbassani, S., Ghasemzadeh, M., Nikfar, E., Heydari-Yazdi, A. S., Charkazi, A., & Derakhshanpour, F. (2022). Grief experience after deaths: Comparison of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 causes. Journal of Patient Experience, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbi, C. M. C., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Z. (2020). Early parental loss in childhood and depression in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-controlled studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J., Spiegel, J. A., & Papa, A. (2020). Pre-loss grief in family members of COVID-19 patients: Recommendations for clinicians and researchers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 12(S1), S90–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirrine, E. H., Kliner, O., & Gollery, T. J. (2023). College student experiences of grief and loss amid the COVID-19 global pandemic. Journal of Death and Dying, 87(3), 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smid, G. E. (2020). A framework of meaning attribution following loss. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1776563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, P. P. B., Santos, M. A., & Oliveira-Cardoso, É. A. (2024). Emotional suffering after the COVID-19 pandemic: Grieving the loss of family members in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(11), 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, P. P. B., Souza, C., Rodrigues, E. C. G., Santos, M. A. D., & Oliveira-Cardoso, É. A. (2023). Family grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 39(2), e00058022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2021). Bereavement in times of COVID-19: A review and theoretical framework. Omega, 82(3), 500–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X., Yu, C. C., & Low, J. (2022). Exploring loss and grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review of qualitative studies. Annals Singapore, 51(10), 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. (2022). COVID-19: True global death toll from pandemic is almost 15 million, says WHO. BMJ, 377, o1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummel, D., Vachon, M., & Guité-Verret, A. (2022). Acknowledging bereavement, strengthening communities: Introducing an online compassionate community initiative for the recognition of pandemic grief. American Journal of Community Psychology, 69(3–4), 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K., & Jackson, D. (2023). Public expressions of grief and the role of social media in grieving and effecting change. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schaik, T., Brouwer, M. A., Knibbe, N. E., Knibbe, H. J. J., & Teunissen, S. C. C. M. (2022). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on grief experiences of bereaved relatives: An overview review. Omega, 302228221143861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedder, A., Boerner, K., Stokes, J. E., Schut, H. A. W., Boelen, P. A., & Stroebe, M. S. (2022). A systematic review of loneliness in bereavement: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitorino, J. V., Duarte, B. V., Ali, A. M., & Laranjeira, C. (2024). Compassionate engagement of communities in support of palliative and end-of-life care: Challenges in post-pandemic era. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1489299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakam, G. K., Montgomery, J. R., Biesterveld, B. E., & Brown, C. S. (2020). Not dying alone—Modern compassionate care in the COVID-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(24), e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C. L., Wladkowski, S. P., Gibson, A., & White, P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. (2020). Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Family Process, 59(3), 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Age | Sex | Race | Education (Years) | Number of Losses to COVID-19 | Type of Bond with Deceased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 50 | Male | White | <8 | One | Mother |

| P2 | 59 | Male | White | ≥8 | One | Spouse |

| P3 | 78 | Female | White | <8 | One | Spouse |

| P4 | 55 | Female | White | <8 | Two | Mother/Sister |

| P5 | 79 | Female | White | <8 | One | Son |

| P6 | 30 | Female | White | ≥8 | One | Grandmother |

| P7 | 65 | Female | White | <8 | One | Spouse |

| P8 | 84 | Female | White | <8 | One | Spouse |

| P9 | 54 | Female | White | ≥8 | One | Father |

| P10 | 68 | Female | Non-white | <8 | One | Mother |

| P11 | 56 | Male | Non-white | <8 | One | Mother |

| P12 | 41 | Female | Non-white | ≥8 | Two | Sister/Cousin |

| P13 | 32 | Female | White | ≥8 | Three | Uncle/Aunt/Cousin |

| P14 | 55 | Male | White | <8 | One | Brother |

| P15 | 40 | Female | Non-white | ≥8 | One | Mother |

| P16 | 36 | Male | White | ≥8 | One | Mother |

| P17 | 59 | Female | White | <8 | One | Mother |

| P18 | 46 | Female | White | ≥8 | One | Spouse |

| P19 | 68 | Female | Non-white | <8 | One | Cousin |

| P20 | 28 | Female | Non-white | ≥8 | Two | Father/Uncle |

| P21 | 43 | Female | White | ≥8 | One | Spouse |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lima, P.K.G.C.d.; Laranjeira, C.; Carreira, L.; Baldissera, V.D.A.; Meireles, V.C.; Baccon, W.C.; Dias, L.E.; Ali, A.M.; Mello, F.F.; Tostes, M.F.d.P.; et al. Loss and Grief Among Bereaved Family Members During COVID-19 in Brazil: A Grounded Theory Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060829

Lima PKGCd, Laranjeira C, Carreira L, Baldissera VDA, Meireles VC, Baccon WC, Dias LE, Ali AM, Mello FF, Tostes MFdP, et al. Loss and Grief Among Bereaved Family Members During COVID-19 in Brazil: A Grounded Theory Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060829

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Paola Kallyanna Guarneri Carvalho de, Carlos Laranjeira, Lígia Carreira, Vanessa Denardi Antoniassi Baldissera, Viviani Camboin Meireles, Wanessa Cristina Baccon, Lashayane Eohanne Dias, Amira Mohammed Ali, Fernanda Fontes Mello, Maria Fernanda do Prado Tostes, and et al. 2025. "Loss and Grief Among Bereaved Family Members During COVID-19 in Brazil: A Grounded Theory Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060829

APA StyleLima, P. K. G. C. d., Laranjeira, C., Carreira, L., Baldissera, V. D. A., Meireles, V. C., Baccon, W. C., Dias, L. E., Ali, A. M., Mello, F. F., Tostes, M. F. d. P., & Salci, M. A. (2025). Loss and Grief Among Bereaved Family Members During COVID-19 in Brazil: A Grounded Theory Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060829