Psychometric Properties and the Network Analysis of the Turkish Version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale: Associations with Psychological Distress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Flourishing: Conceptualization and Assessment Based on Keyes’s Model

2.2. Flourishing and Psychological Distress

2.3. The Current Study

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Translation of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. The Multidimensional Flourishing Scale

3.3.2. Flourishing Scale

3.3.3. Kessler Distress Scale (K10)

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

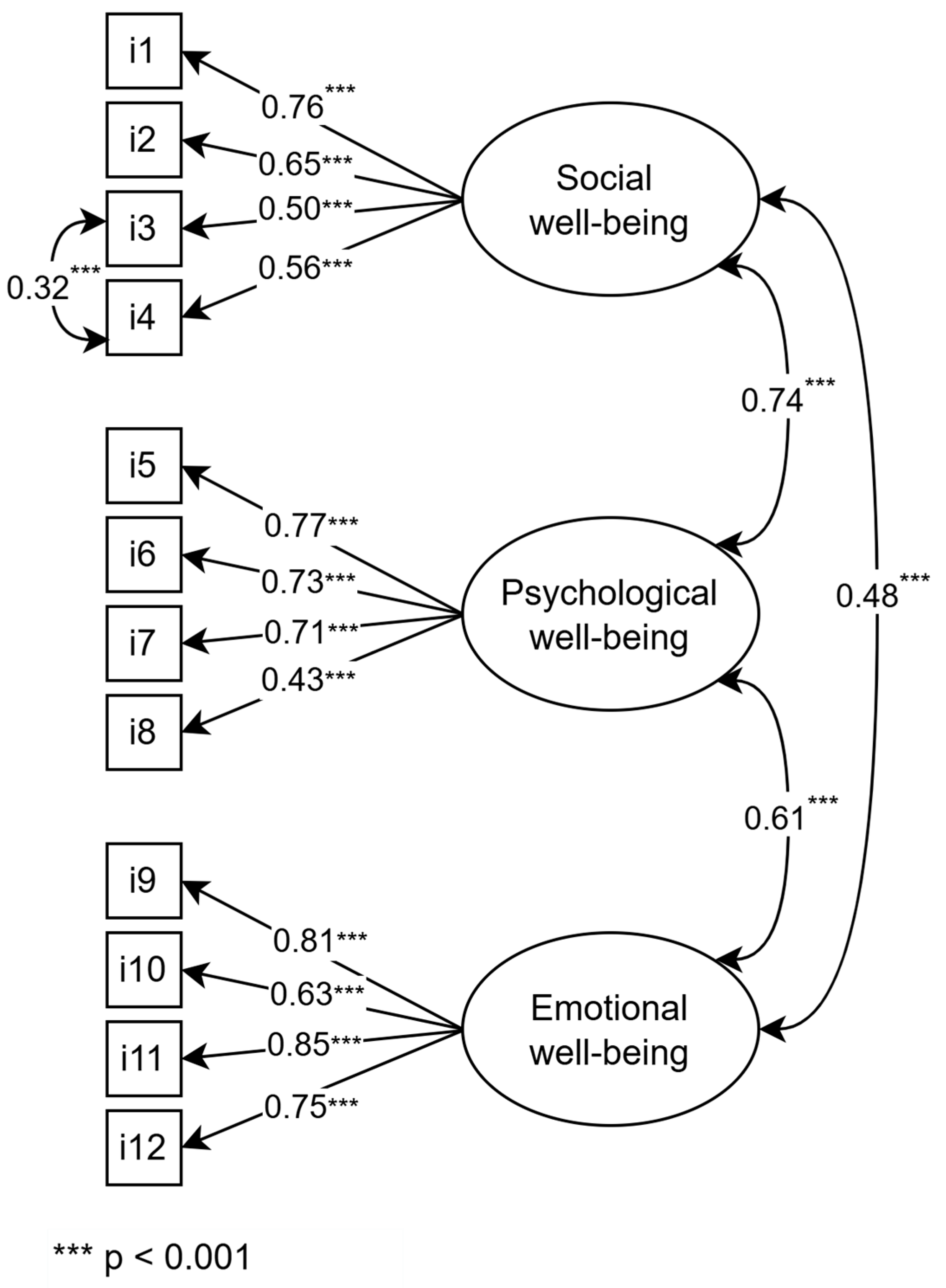

4.1. Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale

| Item No | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Factor Loadings | Item Total Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.68 | 0.90 | −0.82 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.60 |

| 2 | 3.38 | 0.91 | −0.66 | 0.14 | 0.65 | 0.61 |

| 3 | 3.39 | 0.89 | −0.60 | 0.16 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| 4 | 3.64 | 0.80 | −0.74 | 0.99 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| 5 | 3.59 | 1.03 | −0.81 | 0.20 | 0.77 | 0.69 |

| 6 | 3.51 | 0.95 | −0.63 | 0.09 | 0.73 | 0.66 |

| 7 | 3.12 | 1.07 | −0.30 | −0.56 | 0.71 | 0.70 |

| 8 | 4.29 | 0.83 | −1.25 | 1.72 | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| 9 | 3.27 | 1.09 | −0.35 | −0.51 | 0.81 | 0.73 |

| 10 | 3.73 | 1.08 | −0.59 | −0.42 | 0.63 | 0.60 |

| 11 | 3.17 | 1.14 | −0.29 | −0.66 | 0.85 | 0.72 |

| 12 | 3.27 | 1.09 | −0.27 | −0.45 | 0.75 | 0.67 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social well-being | 14.09 | 2.61 | 1 | |||

| 2. Psychological well-being | 14.48 | 2.98 | 0.53 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. Emotional well-being | 13.42 | 3.66 | 0.36 *** | 0.49 *** | 1 | |

| 4. Flourishing scale | 42.06 | 7.53 | 0.61 *** | 0.70 *** | 0.46 *** | 1 |

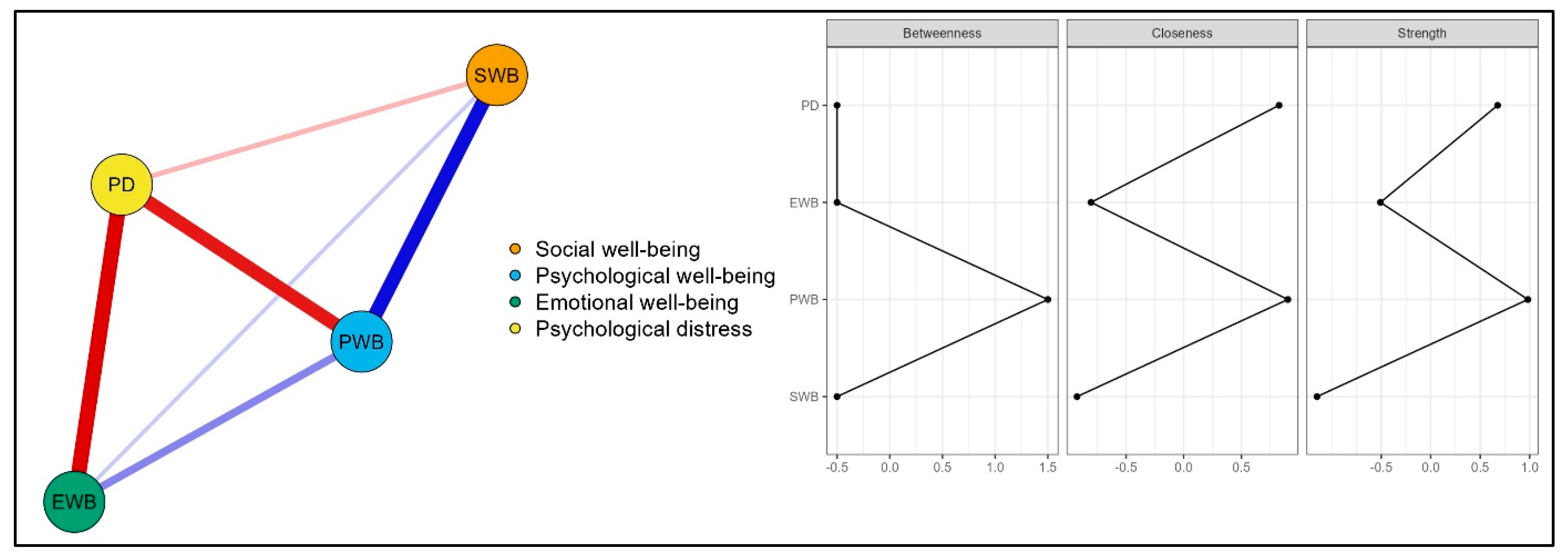

4.2. Relationships Between Indicators of Flourishing and Psychological Distress Symptoms

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agenor, C., Conner, N., & Aroian, K. (2017). Flourishing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altun, Y., Özen, M., & Kuloğlu, M. M. (2019). Psikolojik sıkıntı ölçeğinin Türkçe uyarlaması: Geçerlilik ve güvenilirlik çalışması. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi, 20, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 36(6), 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Sorensen, C. K., & Walker, D. A. (2014). Introduction to research in education (9th ed.). Watsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Azañedo, C. M., Sastre, S., Artola, T., Alvarado, J. M., & Jiménez-Blanco, A. (2020). Social intelligence and psychological distress: Subjective and psychological well-being as mediators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, N. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Briganti, G., Fried, E. I., & Linkowski, P. (2019). Network analysis of contingencies of self-worth scale in 680 university students. Psychiatry Research, 272, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş., Kılıç-Çakmak, E., Akgün, Ö. E., Karadeniz, Ş., & Demirel, F. (2014). Bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri (17. baskı). Pegem. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, S. (2019). Health and well-being in late life: Gender differences worldwide. Frontiers in Medicine, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, E. S., Kim, K. H., & Erlen, J. A. (2007). Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(4), 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Chen, Z. (2008). Extended bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika, 95(3), 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2024). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41(2), 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P., López-Franco, M. D., Capelas, M. L., Almeida, S., Bennett, P. M., Miranda da Silva, M., Teixeira, G., Nunes, E., Lucas, P., & Gaspar, F. (2024). Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of measurement instruments: A practical guideline for novice researchers. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 17, 2701–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, G., & Paul, J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHaan, C. R., & Ryan, R. M. (2014). Symptoms of wellness: Happiness and eudaimonia from a self-determination perspective. In M. Sheldon, & R. E. Lucas (Eds.), Stability of happiness (pp. 37–55). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Di Consiglio, M., Fabrizi, G., Conversi, D., La Torre, G., Pascucci, T., Lombardo, C., Violani, C., & Couyoumdjian, A. (2021). Effectiveness of NoiBene: A Web-based programme to promote psychological well-being and prevent psychological distress in university students. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 13(2), 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doré, I., O’Loughlin, J. L., Sabiston, C. M., & Fournier, L. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of the mental health continuum–short form in French Canadian young adults. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(4), 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drapeau, A., Marchand, A., & Beaulieu-Prévost, D. (2012). Epidemiology of psychological distress. In L. Lebate (Ed.), Mental illnesses: Understanding, prediction and control (pp. 105–134). InTech. [Google Scholar]

- du Plooy, D. R., Lyons, A., & Kashima, E. S. (2019). Predictors of flourishing and psychological distress among migrants to Australia: A dual continuum approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekşi, H., Demirci, İ., Albayrak, İ., & Ekşi, F. (2022). The predictive roles of character strengths and personality traits on flourishing. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 9(2), 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, L. R., & Scandura, T. A. (Eds.). (2023). The SAGE handbook of survey development and application. SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2008). Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics, 9(3), 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Zhao, W., Chu, X., Chen, H., & Li, W. (2022). A network analysis of the relationships between behavioral inhibition/activation systems and problematic mobile phone use. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 832933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençöz, T., Özlale, Y., & Lennon, R. (2004). Direct and indirect effects of social support on psychological well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 32(5), 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravetter, F. J., & Forzano, L. B. (2012). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (4th ed.). Watsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati, S., Oravecz, Z., Brick, T. R., & Roeser, R. W. (2022). Assessing psychological well-being in early adulthood: Empirical evidence for the structure of daily well-being via network analysis. Applied Developmental Science, 26(2), 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hides, L., Quinn, C., Stoyanov, S., Cockshaw, W., Kavanagh, D. J., Shochet, I., Deane, F., Kelly, P., & Keyes, C. L. (2020). Testing the interrelationship between mental well-being and mental distress in young people. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(3), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, M., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Kuppens, P. (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 901–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höltge, J., Cowden, R. G., Lee, M. T., Bechara, A. O., Joynt, S., Kamble, S., Khalansky, V. V., Shtanko, L., Kurniati, N. M. T., Tymchenko, S., Voytenko, V. L., McNeely, E., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2023). A systems perspective on human flourishing: Exploring cross-country similarities and differences of a multisystemic flourishing network. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(5), 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W. C., Huang, N. C., Li, C. L., & Hu, S. C. (2024). Exploring determinants of flourishing: A comprehensive network analysis of retirees in Taiwan. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppert, F. A. (2009). Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1(2), 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iasiello, M., van Agteren, J., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Lo, L., Fassnacht, D. B., & Westerhof, G. J. (2022). Assessing mental wellbeing using the mental health continuum—Short form: A systematic review and meta-analytic structural equation modelling. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(4), 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S., Yu, B., Feng, C., Jia, P., Xu, P., & Yang, S. (2023). Occupational burnout, flourishing and job satisfaction among HIV/AIDS healthcare workers in Western China: A network analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, O., London, A., & Vinkó, T. (2020). Stability of network centrality measures: A numerical study. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2015). Why flourishing? In D. Harward (Ed.), Well-being and higher education (pp. 99–107). Bringing Theory to Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L., Wissing, M., Potgieter, J. P., Temane, M., Kruger, A., & Van Rooy, S. (2008). Evaluation of the mental health continuum–short form (MHC–SF) in setswana-speaking South Africans. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(3), 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knapstad, M., Sivertsen, B., Knudsen, A. K., Smith, O. R. F., Aarø, L. E., Lønning, K. J., & Skogen, J. C. (2021). Trends in self-reported psychological distress among college and university students from 2010 to 2018. Psychological Medicine, 51(3), 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolaczyk, E. D., & Krivitsky, P. N. (2015). On the question of effective sample size in network modeling: An asymptotic inquiry. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 30(2), 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landvreugd, A., van de Weijer, M. P., Pelt, D. H., & Bartels, M. (2024). Connecting the dots: Using a network approach to study the wellbeing spectrum. Current Psychology, 43(34), 27365–27376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurene, K. R., Kodukula, G., Lechner, W. V., Grega, C., Lumpkin, E., & Kenne, D. R. (2024). Assessment of psychological distress as a function of positive psychological variables during the COVID-19 pandemic: A university longitudinal study. Journal of American College Health, 72(1), 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecuona, O., Lin, C. Y., Rozgonjuk, D., Norekvål, T. M., Iversen, M. M., Mamun, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Lin, T., & Pakpour, A. H. (2022). A network analysis of the fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S): A large-scale cross-cultural study in Iran, Bangladesh, and Norway. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Mamun, M. A., Al-Mamun, F., Ullah, I., Hosen, I., Zia, S. A., Poorebrahim, A., Pourgholami, M., Lin, C., Pontes, H. M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2023). A network analysis of the Internet disorder scale–short form (IDS9-SF): A large-scale cross-cultural study in Iran, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Current Psychology, 42(25), 21994–22003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L., Niu, Z., Mei, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2022). A network analysis approach to the relationship between fear of missing out (FoMO), smartphone addiction, and social networking site use among a sample of Chinese university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, D. K., Preszler, J., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2018). A network of dark personality traits: What lies at the heart of darkness? Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, M. (2010). How to factor-analyze your data right: Do’s, don’ts, and how-to’s. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesurado, B., Crespo, R. F., Rodríguez, O., Debeljuh, P., & Carlier, S. I. (2021). The development and initial validation of a multidimensional flourishing scale. Current Psychology, 40, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M. C., Marchetti, I., & Beevers, C. G. (2019). Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(4), 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C. J., Balk, E. M., & Roth, A. J. (2010). Distress, anxiety, depression, and emotional well-being in African-American men with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19(10), 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, C. P. (2023). Eudaimonic well-being. In F. Maggino (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 2212–2214). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, L. F., Fowers, B. J., Kiknadze, N. C., & Calder, A. J. (2025). A close analysis of eight flourishing measures. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 20(1), 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, L. (2022). An illness of isolation, a disease of disconnection: Depression and the erosion of we-experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 928186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raibley, J. R. (2012). Happiness is not well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 1105–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rando, B., Abreu, A. M., & Blanca, M. J. (2023). New evidence on the psychometric properties of the portuguese version of the flourishing scale: Measurement invariance across gender. Current Psychology, 42, 22450–22461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, D. B. (1999). Human flourishing and the appeal to human nature. Social Philosophy and Policy, 16(1), 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, I., Ferro, M. A., Patte, K. A., Diener, E., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2020). Measurement invariance of the flourishing scale among a large sample of Canadian adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M., & Cho, E. (2022). An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organizational Research Methods, 25(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond ponce de leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G., & Banerjee, S. (2021). Validation of the multidimensional flourishing scale and exploration of its relationship with the big-five personality traits in India. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 9(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N., & Kuljanin, G. (2008). Measurement invariance: Review of practice and implications. Human Resource Management Review, 18(4), 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H., Westerhof, G. J., De Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). What factors are associated with flourishing? Results from a large representative national sample. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 1351–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siddik, M. A. B., Ali, A., Miah, S., Hasan, M., Ahmed, M., & Sunna, T. C. (2024). Psychological disorders among college going students: A post COVID-19 insight from Bangladesh. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 15, 100686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderqvist, F., & Larm, P. (2023). Psychometric evaluation of the mental health continuum–short form in Swedish adolescents. Current Psychology, 42(3), 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J. L., Arnett, J. J., & Leis, J. A. (2009). Emerging adulthood: Learning and development during the first stage of adulthood. In M. C. Smith, & N. DeFrates-Densch (Eds.), Handbook of research on adult learning and development (pp. 34–67). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Telef, B. B. (2013). Psikolojik iyi oluş ölçeği: Türkçeye uyarlama, geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 28(3), 374–384. [Google Scholar]

- Van Borkulo, C. D., Borsboom, D., Epskamp, S., Blanken, T. F., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., & Waldorp, L. J. (2014). A new method for constructing networks from binary data. Scientific Reports, 4(1), 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(31), 8148–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, I., Lucassen, P. L., van Weel, C., & Speckens, A. E. (2017). A cross-sectional examination of psychological distress, positive mental health and their predictors in medical students in their clinical clerkships. BMC Medical Education, 17, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viertiö, S., Kiviruusu, O., Piirtola, M., Kaprio, J., Korhonen, T., Marttunen, M., & Suvisaari, J. (2021). Factors contributing to psychological distress in the working population, with a special reference to gender difference. BMC Public Health, 21, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., Zheng, Z., Tang, Y., Zhang, R., Lu, Q., Wang, B., & Sun, Q. (2022). Psychological distress and its influencing factors among psychiatric nurses in China: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 948786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathington, B. L., Cunningham, C. J. L., & Pittenger, D. J. (2010). Research methods for the behavioral and social sciences. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R., & Rodriguez, J. E. (2022). Why overfitting is not (usually) a problem in partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 27(5), 822–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winefield, H. R., Gill, T. K., Taylor, A. W., & Pilkington, R. M. (2012). Psychological well-being and psychological distress: Is it necessary to measure both? Psychology of Well-Being: Theory, Research and Practice, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Sukpasjaroen, K., Wu, Y., Wang, L., Chankoson, T., & Cai, E. (2022). Predicting nursing students’ psychological well-being: Network analysis based on a model of thriving through relationships. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucoloto, M. L., Galdino, G., & Martinez, E. Z. (2024). An instrument of screening criteria to assess individualized high-risk sexual behavior to be applied in the Brazilian population: Translation and cross-cultural adaptation. Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy, 46, S122–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J. P., Osin, E. N., Cieciuch, J., Adams, B. G., Ardi, R., Bălţătescu, S., Bogomaz, S., Bhomi, A. L., Clinton, A., De Clunie, G. T., Czarna, A. Z., Esteves, C., Gouveia, V., Halik, M. H. J., Hosseini, A., Khanhatryan, N., Kamble, S. V., Kawula, A., & Maltby, J. (2018). The mental health continuum-short form: The structure and application for cross-cultural studies–A 38 nation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1034–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Invariance | X2 | df | ΔX2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 131.447 | 50 | 0.933 | 0.912 | 0.077 | ||||

| Males | 114.967 | 50 | 0.927 | 0.903 | 0.083 | ||||

| Configural | 246.440 | 100 | 0.930 | 0.908 | 0.079 | ||||

| Metric | 252.858 | 109 | 7.202(9) ns | 0.931 | 0.917 | 0.076 | 0.001 | 0.009 | −0.003 |

| Scalar | 263.221 | 118 | 8.83 (9) ns | 0.931 | 0.923 | 0.073 | 0.000 | 0.006 | −0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dadandı, İ.; Aydın, F. Psychometric Properties and the Network Analysis of the Turkish Version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale: Associations with Psychological Distress. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060800

Dadandı İ, Aydın F. Psychometric Properties and the Network Analysis of the Turkish Version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale: Associations with Psychological Distress. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060800

Chicago/Turabian StyleDadandı, İbrahim, and Fatih Aydın. 2025. "Psychometric Properties and the Network Analysis of the Turkish Version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale: Associations with Psychological Distress" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060800

APA StyleDadandı, İ., & Aydın, F. (2025). Psychometric Properties and the Network Analysis of the Turkish Version of the Multidimensional Flourishing Scale: Associations with Psychological Distress. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060800