Unraveling the Longitudinal Relationships Among Parenting Stress, Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior, and Risk of Learning Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relationships Between Parenting Stress and Risk of Learning Disorder

2.2. Problem Behavior as a Mediator

2.3. The Present Study

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Parenting Stress

3.2.2. Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior

3.2.3. Risk of Learning Disorder

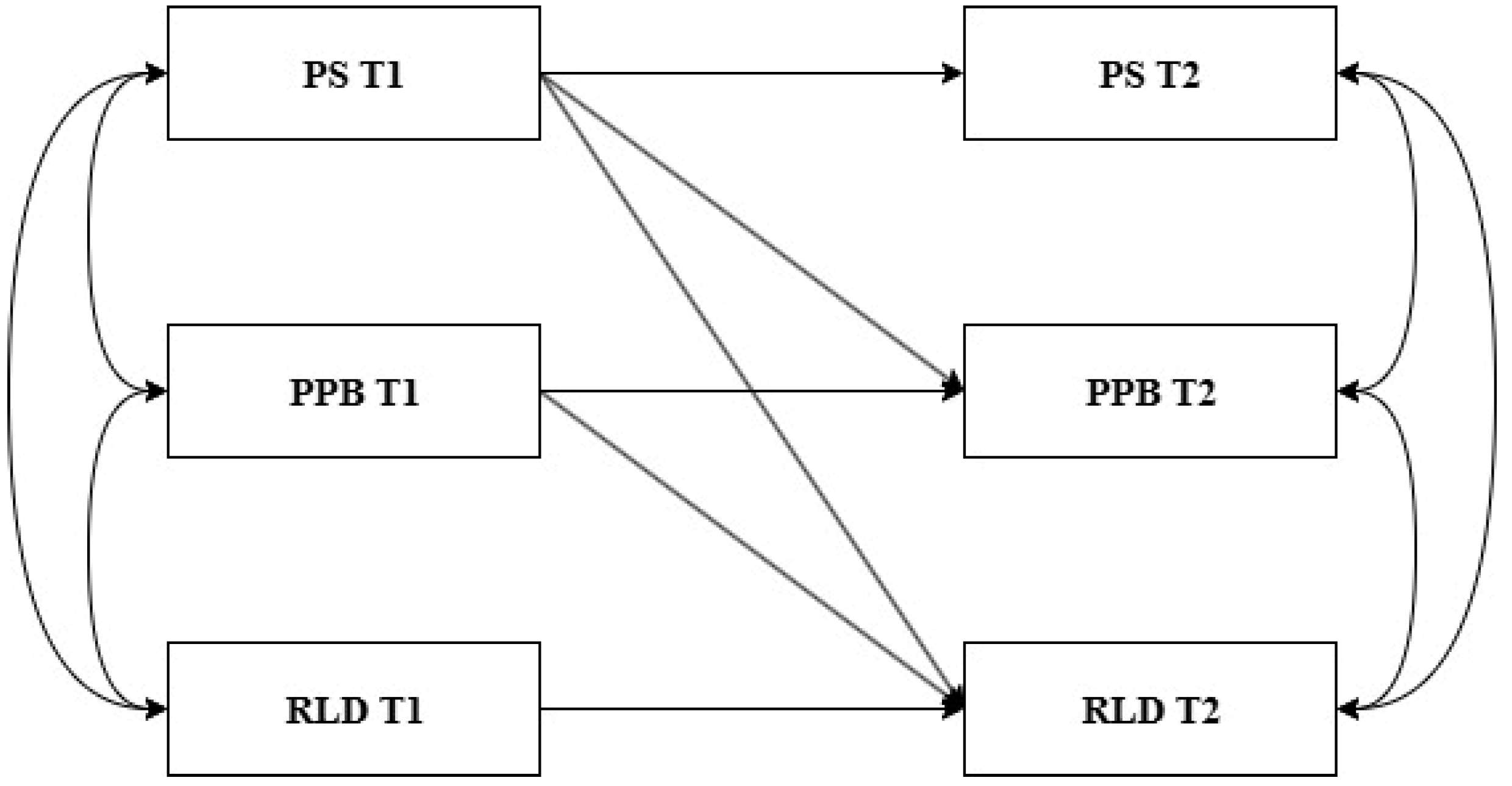

3.3. Analytic Plan

4. Results

4.1. Test of Common Method Bias

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analyses

4.3. Multicollinearity Diagnostics

4.4. Measurement Invariance

4.5. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The Effect of Parenting Stress on Preschoolers’ Risk of Learning Disorder

5.2. The Mediating Role of Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior

6. Limitations and Future Study Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting stress index-short form (Vol. 118). Pediatric Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, R. R., & Brunner, J. F. (1995). Development of a parenting alliance inventory. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 24(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auriemma, D. L., Ding, Y., Zhang, C., Rabinowitz, M., Shen, Y., & Lantier-Galatas, K. (2022). Parenting stress in parents of children with learning disabilities: Effects of cognitions and coping styles. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 37(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becherer, J., Köller, O., & Zimmermann, F. (2021). Externalizing behaviour, task-focused behaviour, and academic achievement: An indirect relation? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benasich, A. A., Curtiss, S., & Tallal, P. (1993). Language, learning, and behavioral disturbances in childhood: A longitudinal perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(3), 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, K. L., Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., Greenberg, M. T., Lochman, J. E., McMahon, R. J., & Pinderhughes, E. (2010). The effects of a multiyear universal social–emotional learning program: The role of student and school characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacci, P., Storti, M., Tobia, V., & Suardi, A. (2016). Specific learning disorders: A look inside children’s and parents’ psychological well-being and relationships. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(5), 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozatlı, L., Aykutlu, H. C., Sivrikaya Giray, A., Ataş, T., Özkan, Ç., Güneydaş Yıldırım, B., & Görker, I. (2024). Children at risk of specific learning disorder: A study on prevalence and risk factors. Children, 11(7), 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiner, H., Ford, M., Gadsden, V. L., & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Parenting knowledge, attitudes, and practices. In Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0–8. National Academies Press (US). [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechel, C., Friedmann, A., Eber, S., Behrends, U., Mall, V., & Nehring, I. (2024). The change of psychosocial stress factors in families with infants and toddlers during the COVID-19 pandemic. A longitudinal perspective on the CoronabaBY study from Germany. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 12, 1354089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlaka, V., Wu, Q., Wu, S., & Churakova, I. (2019). Internalizing and externalizing behaviors among Ukrainian children: The role of family communication and maternal coping. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-C., Cheng, S.-L., Xu, Y., Rudasill, K., Senter, R., Zhang, F., Washington-Nortey, M., & Adams, N. (2022). Transactions between problem behaviors and academic performance in early childhood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Yu, W., Chen, R., Zhang, M., Wang, L., & Tao, F. (2021). The influence of preschool children’s lifestyle on emotional and behavioral problems. Modern Preventive Medicine, 48, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., & Zhou, L. (2018). The level and influencing factors of parenting stress in parents of preschool children. Military Nursing, 35(2), 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H., Liu, X., Li, Y., & Li, Y. (2021). Is parenting a happy experience? Review on parental burnout. Psychological Development and Education, 37, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1994). The earth is round (p < 0.05). American Psychologist, 49(12), 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A. M., Chan, E. S., Gaye, F., Harmon, S. L., & Kofler, M. J. (2024). The role of working memory and organizational skills in academic functioning for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology, 38(6), 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, K., Frech, N., Sanchez, A. L., Hagan, M. B., Bagner, D. M., & Comer, J. S. (2021). Caregiver stress and cultural identity in families of preschoolers with developmental delay and behavioral problems. Infant Mental Health Journal, 42(4), 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, M. E., Veldorale-Griffin, A., Petren, R. E., & Mullis, A. K. (2014). Parent–child interaction therapy: A meta-analysis of child behavior outcomes and parent stress. Journal of Family Social Work, 17(3), 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, F., Operto, F. F., De Giacomo, A., Margari, L., Frolli, A., Conson, M., Ivagnes, S., Monaco, M., & Margari, F. (2016). Parenting stress among parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Psychiatry Research, 242, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K., & Ross, E. (2017). Parenting stress and parental efficacy. In Parental stress and early child development: Adaptive and maladaptive outcomes (pp. 263–284). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimpelaere, E. N., Soenens, B., Prinzie, P., Waterschoot, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Morbée, S., Schrooyen, C., & De Pauw, S. S. (2023). Parents’ stress, parental burnout, and parenting behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparing parents of children with and without complex care needs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(12), 3681–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulou, S., Rydell, A.-M., Thorell, L. B., & Bohlin, G. (2007). Impact of executive functioning and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on children’s peer relations and school performance. Developmental Neuropsychology, 32(1), 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Eggum, N. D. (2010). Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshraghi, A. A., Cavalcante, L., Furar, E., Alessandri, M., Eshraghi, R. S., Armstrong, F. D., & Mittal, R. (2022). Implications of parental stress on worsening of behavioral problems in children with autism during COVID-19 pandemic: “The spillover hypothesis”. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(4), 1869–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A. M. (2010). Insufficient discriminant validity: A comment on Bove, Pervan, Beatty, and Shiu (2009). Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, T., & Börnert-Ringleb, M. (2023). The intersection of learning difficulties and behavior problems—A scoping review of intervention research. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1268904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L., Ke, X., Xue, Q., Chi, X., Jia, J., Chen, P., & Lu, Z. (2008). Maternal parenting stress and related factors in mothers of 6-month infants. Chinese Pediatrics of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, 27(6), 457–459. [Google Scholar]

- Glozman, J. M., & Konina, S. M. (2014). Prevention of learning disability in the preschool years. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 146, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L., Popovic, M., Rebagliato, M., Estarlich, M., Moirano, G., Barreto-Zarza, F., Richiardi, L., Arranz, E., Santa-Marina, L., Zugna, D., Ibarluzea, J., & Pizzi, C. (2024). Socioeconomic position, family context, and child cognitive development. European Journal of Pediatrics, 183(6), 2571–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (2013). Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A. K. (2022). Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 37(5), 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J. W., & Lee, H. (2018). Effects of parenting stress and controlling parenting attitudes on problem behaviors of preschool children: Latent growth model analysis. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 48(1), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskett, M. E., Ahern, L. S., Ward, C. S., & Allaire, J. C. (2006). Factor structure and validity of the parenting stress index-short form. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.-Y., Yu, M., Ning, M., Cui, X.-C., Jia, L.-Y., Li, R.-Y., & Wan, Y.-H. (2023). The role of mother-child relationship in the association between maternal parenting stress and emotional and behavioral problems in preschool children. Zhongguo Dang dai er ke za zhi = Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 25(4), 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J., Mayer, A., Scharke, W., Heim, S., & Günther, T. (2020). Development of behavior problems in children with and without specific learning disorders in reading and spelling from kindergarten to fifth grade. Scientific Studies of Reading, 24(1), 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-J. (2018). Parental stress in families of children with disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(4), 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafary, Z. (2022). The role of parental stress in predicting academic and social adjustment of students with learning disabilities. Social Determinants Health, 8(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyner, R. E., & Wagner, R. K. (2020). Co-occurrence of reading disabilities and math disabilities: A meta-analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 24(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. K., Choi, H. J., & Chung, M. R. (2022). Coparenting and parenting stress of middle-class mothers during the first year: Bidirectional and unidirectional effects. Journal of Family Studies, 28(2), 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, J., Du, Y., & Xia, L. (2005). Reliability and validity of “children strengths and difficulties questionnaire” in Shanghai norm. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry, 17(1), 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, T., Sullivan, A. L., & Kim, J. (2021). Externalizing behavior problems and low academic achievement: Does a causal relation exist? Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Bünning, M., Kaiser, T., & Hipp, L. (2022). Who suffered most? Parental stress and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. JFR-Journal of Family Research, 34(1), 281–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D. (2024). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Deng, H., Zhang, M., Zhang, G., & Lu, Z. (2019). The effect of 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and early parenting stress on preschoolers’ behavioral problems. Psychological Development and Education, 35(1), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Ruiz, V., Romero-Ayuso, D., Toledano-González, A., & Triviño-Juárez, J. M. (2025). Quality of life and parental stress related to executive functioning, sensory processing, and activities of daily living in children and adolescents with neurodevelopmental disorders. PeerJ, 13, e19326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J., Wang, M.-C., Gao, Y., Zeng, H., Yang, W., Chen, W., Zhao, S., & Qi, S. (2021). Refining the parenting stress index–short form (PSI-SF) in Chinese parents. Assessment, 28(2), 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill-Evans, J., & Harrison, M. J. (2001). Parent-child interactions, parenting stress, and developmental outcomes at 4 years. Children’s Health Care, 30(2), 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P. C., Matos, C. D., & Sani, A. I. (2023). Parental stress and risk of child abuse: The role of socioeconomic status. Children and Youth Services Review, 148, 106879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, W. (1993). Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika, 58(4), 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, A. M., Aboulghate, A., Elshaarawy, G. A., Abdallah, A. M., Abdel Raouf, E. R., El-Din, E. M. S., Khadr, Z., El-Saied, M. M., Elabd, M. A., Nassar, M. S., Abouelnaga, M. W., Ashaat, E. A., El-Sonbaty, M. M., Badawy, H. Y., Dewdar, E. M., Salama, S. I., Abdelrahman, M., Abdelmohsen, A. M., Eldeeb, S. E., … ElRifay, A. S. (2023). Prevalence and risk factors of disabilities among Egyptian preschool children: A community-based population study. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadipour, S., Dasht Bozorgi, Z., & Hooman, F. (2021). The role of mental health of mothers of children with learning disabilities in the relationship between parental stress, mother-child interaction, and children’s behavioral disorders. Journal of Client-Centered Nursing Care, 7(2), 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moideen, N., & Mathai, S. (2018). Parental stress of mothers of children with learning disabilities. Researchers World, 9(2), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, K., Kunze, S., Neuhoff, N., Bruder, J., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2014). Specific learning disorder: Prevalence and gender differences. PLoS ONE, 9(7), e103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, K., Snowling, M. J., & Hulme, C. (2020). Introduction to the special issue “comorbidities between reading disorders and other developmental disorders”. Scientific Studies of Reading, 24(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M. R., & Kiany, M. (2021). The Effectiveness of neuropsychological practical exercises on improvingexecutive functions and attention Spanin students with dyslexia. Neuropsychology, 6(23), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F., & Heck, A. (2012). Multivariate data analysis (Vol. 131). Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Muthn, L., & Muthn, B. (2010). Mplus users guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. Muthn & Muthn. [Google Scholar]

- Neece, C. L., Green, S. A., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J., Vickers, K., Atkinson, L., Gonzalez, A., Wekerle, C., & Levitan, R. (2012). Parenting stress mediates between maternal maltreatment history and maternal sensitivity in a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(5), 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L., & Ansari, D. (2019). Are specific learning disorders truly specific, and are they disorders? Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 17, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B. F., & Dudok, R. (2023). Strengths and difficulties among adolescent with and without Specific Learning Disorders (SLD). Children, 10(11), 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polderman, T. J., Boomsma, D. I., Bartels, M., Verhulst, F. C., & Huizink, A. C. (2010). A systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122(4), 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J. (2015). Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G., Li, B., Xu, L., Ai, S., Li, X., Lei, X., & Dou, G. (2024). Parenting style and young children’s executive function mediate the relationship between parenting stress and parenting quality in two-child families. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Schlack, R., & Otto, C. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(6), 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, J. M. (2018). Thinking clearly about correlations and causation: Graphical causal models for observational data. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(1), 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousi-Laine, M. (2018). Internalizing, externalizing and attention problems among learning disability subgroups. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:jyu-201808013678 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Sahu, A., Bhargava, R., Sagar, R., & Mehta, M. (2018). Perception of families of children with specific learning disorder: An exploratory study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40(5), 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmento-Henrique, R., Quintanilla, L., Lucas-Molina, B., Recio, P., & Giménez-Dasí, M. (2020). The longitudinal interplay of emotion understanding, theory of mind, and language in the preschool years. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(3), 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W., Ennemoser, M., Roth, E., & Küspert, P. (1999). Kindergarten prevention of dyslexia: Does training in phonological awareness work for everybody? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(5), 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, P., Bailey, D. B., & Auer, C. (1994). Preschool eligibility determination for children with known or suspected learning disabilities under IDEA. Journal of Early Intervention, 18(4), 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, A., Akbarzadeh, F., Moharreri, F., Soltanifar, A., Ebrahimi, A., Mokhber, N., Minoocherhr, A., & Naqvi, S. S. A. (2015). Comparison of parental stress among mothers and fathers of children with autistic spectrum disorder in Iran. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 20(1), 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann, S., Otto, Y., Andreas, A., von Klitzing, K., & Klein, A. M. (2015). Maternal stress and internalizing symptoms in preschoolers: The moderating role of narrative coherence. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(2), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, E. A., Walker, M. A., & Vaughn, S. (2017). The effects of reading fluency interventions on the reading fluency and reading comprehension performance of elementary students with learning disabilities: A synthesis of the research from 2001 to 2014. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50(5), 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A. L., Kohli, N., Farnsworth, E. M., Sadeh, S., & Jones, L. (2017). Longitudinal models of reading achievement of students with learning disabilities and without disabilities. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(3), 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taris, T. W., & Kompier, M. A. (2014). Cause and effect: Optimizing the designs of longitudinal studies in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 28(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2009). Differentiation of cognitive abilities across the life span. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker-Drob, E. M., & Bates, T. C. (2016). Large cross-national differences in gene× socioeconomic status interaction on intelligence. Psychological Science, 27(2), 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkheimer, E., Haley, A., Waldron, M., d’Onofrio, B., & Gottesman, I. I. (2003). Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychological Science, 14(6), 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venta, A., Velez, L., & Lau, J. (2016). The role of parental depressive symptoms in predicting dysfunctional discipline among parents at high-risk for child maltreatment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 3076–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R. K., Zirps, F. A., Edwards, A. A., Wood, S. G., Joyner, R. E., Becker, B. J., Liu, G., & Beal, B. (2020). The prevalence of dyslexia: A new approach to its estimation. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 53(5), 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Xian, Y., Dill, S.-E., Fang, Z., Emmers, D., Zhang, S., & Rozelle, S. (2022). Parenting style and the cognitive development of preschool-aged children: Evidence from rural China. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 223, 105490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-j., Zhang, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). Mothers’ parental psychological flexibility and children’s anxiety: The chain-mediating role of parenting stress and parent-child relationship. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30(6), 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S. G., Finch, J. F., & Curran, P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt, E. G., & Pennington, B. F. (2000). Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Differences by gender and subtype. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33(2), 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K., Wang, F., Wang, W., & Li, Y. (2022). Parents’ education anxiety and children’s academic burnout: The role of parental burnout and family function. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 764824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L., He, J., Wei, X., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, L. (2024). Parental psychological control and adolescent academic achievement: The mediating role of achievement goal orientation. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S., Liu, Z., Peng, P., & Yan, N. (2024). The reciprocal relations between externalizing behaviors and academic performance among school-aged children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Educational Psychology Review, 36(4), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.-y., Zeng, H.-t., Long, X.-n., Peng, W.-t., & Huang, W. (2024). The effect of parenting stress on children’s internalizing problems: Based on tripartite model of familial influence theory and the spillover hypothesis. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32(03), 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M., Wang, J., Liu, P., Guo, Y., Xie, Y., Zhang, L., Su, N., Li, Y., Yu, D., Hong, Q., & Chi, X. (2022). Development, reliability, and validity of the preschool learning skills scale: A tool for early identification of preschoolers at risk of learning disorder in mainland China. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 918163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-f., Guo, F., Chen, Z.-y., & Yuan, T. (2023). Relationship between paternal co-parenting and children’s externalizing problem behavior: The chain mediating effect of maternal parenting stress and maternal parenting self-efficacy. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(4), 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Räsänen, P., Koponen, T., Aunola, K., Lerkkanen, M. K., & Nurmi, J. E. (2020). Early cognitive precursors of children’s mathematics learning disability and persistent low achievement: A 5-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 91(1), 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-j., Ruan, Y., Yang, L., Yao, J., Zhang, A.-h., & Ma, R.-j. (2011). The features of family environment and parental rearing styles of children with learning disorders. Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 29(11), 1063–1066. [Google Scholar]

| Demographics | Types | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex of children | Boys | 133 (46.83%) |

| Girls | 151 (53.17%) | |

| Grades of children | Junior Class of Kindergarten | 73 (25.70%) |

| Middle Class of Kindergarten | 125 (44.01%) | |

| Senior Class of Kindergarten | 86 (30.28%) | |

| One child in the family | Yes | 208 (73.24%) |

| No | 76 (26.76%) | |

| Parental education | Junior high school education and below | 36 (12.68%) |

| Senior high school education | 37 (13.03%) | |

| Post-secondary education | 84 (29.58%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree and above | 127 (44.72%) | |

| Parental working hours | Out of work | 67 (23.59%) |

| Less than 8 h | 81 (28.52%) | |

| 8~10 h | 111 (39.08%) | |

| More than 10 h | 25 (8.80%) | |

| Family annual income | RMB 50,000 and below | 37 (13.03%) |

| RMB 60,000~100,000 | 78 (27.46%) | |

| RMB 110,000~150,000 | 80 (28.17%) | |

| RMB 160,000~200,000 | 33 (11.62%) | |

| RMB 200,000 and above | 56 (19.72%) |

| T1 | T2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Range | Cronbach’s α | M | SD | Range | Cronbach’s α | |

| PS | 2.178 | 0.625 | 1–4.54 | 0.982 | 2.248 | 0.678 | 1–4.88 | 0.985 |

| PPB | 0.496 | 0.325 | 0–1.25 | 0.925 | 0.580 | 0.455 | 0–2.00 | 0.939 |

| RLD | 2.134 | 0.710 | 1–4.50 | 0.963 | 1.987 | 0.708 | 1–4.45 | 0.975 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parenting stress_T1 | - | |||||

| 2. Parenting stress_T2 | 0.518 *** | - | ||||

| 3. Preschoolers’ problem behavior_T1 | 0.292 *** | 0.188 ** | - | |||

| 4. Preschoolers’ problem behavior_T2 | 0.310 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.730 *** | - | ||

| 5. Risk of learning disorder_T1 | 0.333 *** | 0.148 * | 0.527 *** | 0.360 *** | - | |

| 6. Risk of learning disorder_T2 | 0.374 *** | 0.553 *** | 0.420 *** | 0.704 *** | 0.397 *** | - |

| Scale | Invariance | x2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Comparison | Δx2 | p-Value | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | |||||||||||

| (1) Configural | 2419.426 * | 1081 | 0.978 | 0.977 | 0.066 | ||||||

| (2) Metric | 2098.952 * | 1104 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.056 | (2) vs. (1) | 27.824 | 0.223 | 0.005 | −0.010 | |

| PPB | |||||||||||

| (4) Configural | 1653.574 * | 741 | 0.941 | 0.938 | 0.066 | ||||||

| (5) Metric | 1553.993 * | 760 | 0.949 | 0.948 | 0.061 | (5) vs. (4) | 56.774 | p < 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.005 | |

| (6) Partial metric | 1510.373 * | 753 | 0.951 | 0.950 | 0.060 | (6) vs. (4) | 14.676 | 0.260 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| RLD | |||||||||||

| (7) Configural | 6484.380 * | 2776 | 0.881 | 0.878 | 0.069 | ||||||

| (8) Metric | 6570.396 * | 2813 | 0.880 | 0.878 | 0.069 | (8) vs. (7) | 160.713 | p < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| (9) Partial metric | 6556.487 * | 2811 | 0.880 | 0.878 | 0.068 | (9) vs. (7) | 147.659 | p < 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 |

| Path | Mediation Model a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Direct effect | |||||

| T1 PS → T2 PS | 0.518 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 0.414 | 0.618 |

| T1 PS → T2 PPB | 0.109 | 0.040 | 0.007 | 0.033 | 0.190 |

| T1 PPB → T2 PPB | 0.694 | 0.033 | <0.001 | 0.624 | 0.755 |

| T1 PS → T2 RLD | 0.231 | 0.055 | <0.001 | 0.118 | 0.333 |

| T1 PPB → T2 RLD | 0.203 | 0.051 | <0.001 | 0.100 | 0.301 |

| T1 RLD → T2 RLD | 0.247 | 0.044 | <0.001 | 0.164 | 0.335 |

| Indirect effect | |||||

| PS → PPB → RLD | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.025 | 0.003 | 0.041 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Yu, D.; Tang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Lai, X. Unraveling the Longitudinal Relationships Among Parenting Stress, Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior, and Risk of Learning Disorder. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060785

Huang J, Yu D, Tang X, Xu Y, Zhong X, Lai X. Unraveling the Longitudinal Relationships Among Parenting Stress, Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior, and Risk of Learning Disorder. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060785

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jie, Dongqing Yu, Xiaoxue Tang, Yili Xu, Xiao Zhong, and Xiaoqian Lai. 2025. "Unraveling the Longitudinal Relationships Among Parenting Stress, Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior, and Risk of Learning Disorder" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060785

APA StyleHuang, J., Yu, D., Tang, X., Xu, Y., Zhong, X., & Lai, X. (2025). Unraveling the Longitudinal Relationships Among Parenting Stress, Preschoolers’ Problem Behavior, and Risk of Learning Disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 785. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060785