Screening Hospitalized Pregnant Women and Their Male Partners for Possible Distress: A Comparison of the Clinical Usefulness of Two Screening Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. What Tools Are Available for Screening in the Perinatal Period and Which One Can Be the Most Suitable in a Hospital Context?

1.2. Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Modified Whooley Questions

2.2.2. GAD-2

2.2.3. MGMQ

2.2.4. Women’s Views, Understanding, and Interpretation of the Measures

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Statistical Analyses and Effect Size

3. Results

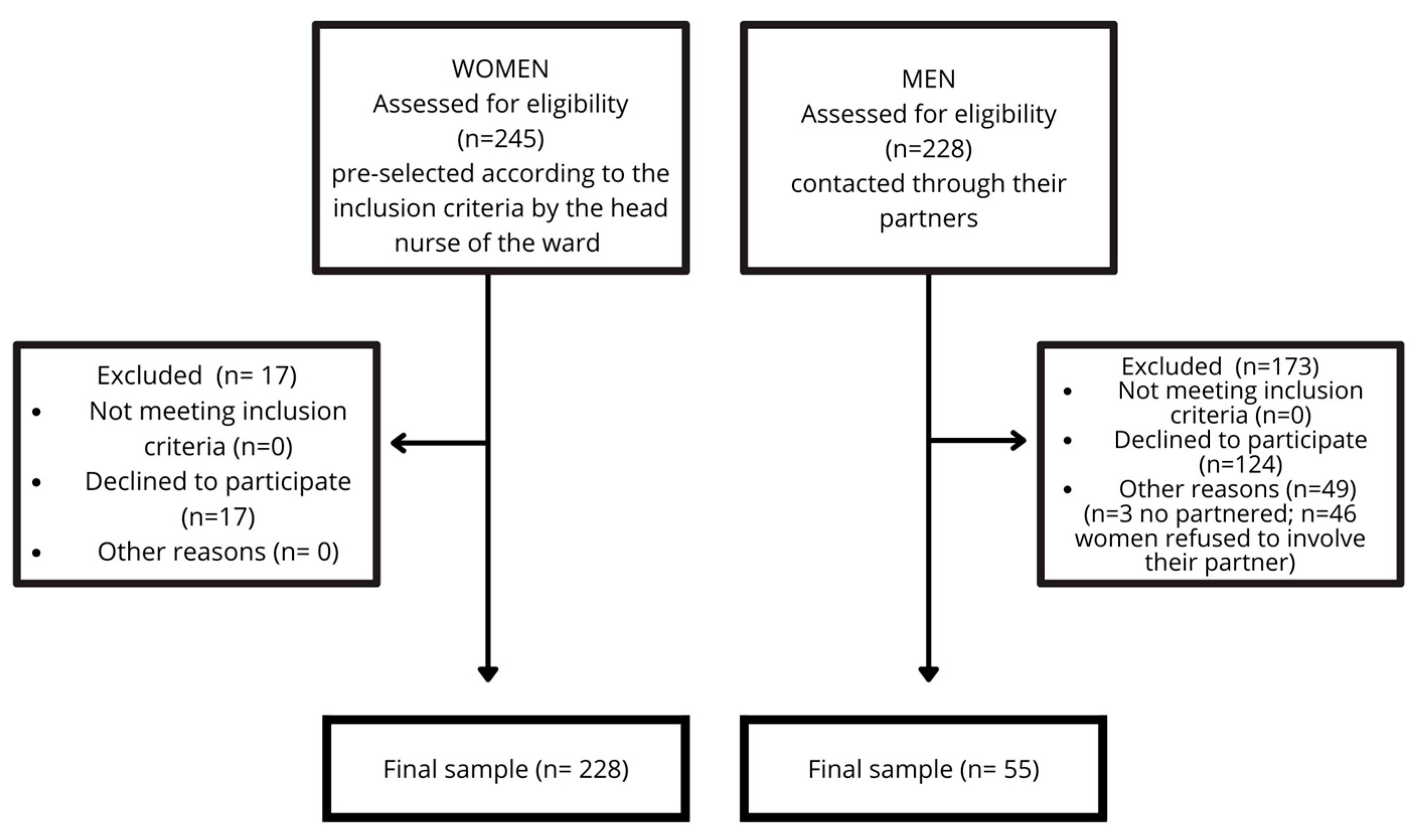

3.1. Participants

3.2. Demographics

3.3. Rates of Positive Screening (MGMQ and Whooley/GAD-2) with Respect to Women’s Sociodemographic and Pregnancy Variables

3.4. Women: Perception and Understanding of the Measures

3.5. Women: Wish-to-Talk to a Health Professional and Their Reasons (MGMQ Q3 and Q4)

3.6. Men: Wish-to-Talk to a Health Professional and Their Reasons (MGMQ Q3 and Q4)

3.7. Comparison of the Two Instruments: Women

3.8. Comparison of the Two Instruments: Men

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASST | Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| GAD-2 | Generalized Anxiety Disorders-2 |

| MGMQ | Matthey Generic Mood Questionnaire |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| PHQ-2 | Patient Health Questionnaire-2 |

| PO | Project Officer |

| Q1 MGMQ | Question 1 of MGMQ, Distress Question |

| Q2 MGMQ | Question 2 of MGMQ, Impact Question (bother) |

| Q3 MGMQ | Question 3 of MGMQ, Reason Question |

| Q4 MGMQ | Question 4 of MGMQ, Wish-to-Talk Question |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| Whooley/GAD-2 | Whooley questions used together with the GAD-2 |

References

- Affonso, D. D., De, A. K., Horowitz, J. A., & Mayberry, L. J. (2000). An international study exploring levels of postpartum depressive symptomatology. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49(3), 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-abri, K., Edge, D., & Armitage, C. J. (2023). Prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 58(11), 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayers, S., Coates, R., Sinesi, A., Cheyne, H., Maxwell, M., Best, C., McNicol, S., Williams, L. R., Uddin, N., Hutton, U., Howard, G., Shakespeare, J., Walker, J. J., Alderdice, F., Jomeen, J., & the MAP Study Team. (2024). Assessment of perinatal anxiety: Diagnostic accuracy of five measures. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 224(4), 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A., Knapp, M., & Parsonage, M. (2016). Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, E., Simonetti, R., Capretti, M., & Sartori, E. (2023). Leggere i bisogni psicologici della donna in area ostetrica. L’intervento psicologico in ospedale: Da un modello di invio ad un modello di screening. In G. Giacalone, & A. Domingo (Eds.), La psicologia ospedaliera in Italia (pp. 307–334). Màrgana Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, A., Nanda, A., Murphy, L., Ball, A. L., Fortney, J., & Katon, J. (2022). A systematic review of screening for perinatal depression and anxiety in community-based settings. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25(1), 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibring, G. L. (1959). Some considerations of the psychological processes in pregnancy. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 14(1), 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruney, T. L., & Zhang, X. (2022). Improving perinatal depression screening and management: Results from a federally qualified health center. Journal of Public Health, 44(4), 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bydlowski, M. (2020). Devenir mère: À l’ombre de la mémoire non consciente. Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Calculator.net. (n.d.). Sample size calculator. Available online: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html?type=1&cl=90&ci=5&pp=30&ps=5000&x=Calculate (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Capretti, M., Tessarin, S., Masserdotti, E., Berruti, N., & Beretta, E. (2022). Cogliere il bisogno psicologico della donna nell’immediato postpartum: Un’esperienza nel puerperio dell’Ospedale Civile di Brescia. In Psicologia della salute: Quadrimestrale di psicologia e scienze della salute: 2, 2022. FrancoAngeli. Available online: http://digital.casalini.it/10.3280/PDS2022-002009 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Condon, J. T., & Corkindale, C. J. (1997). The assessment of depression in the postnatal period: A comparison of four self-report questionnaires. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 31(3), 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, R. K., Bruckheim, H. E., Colpe, L. J., Edwards, E., & White, D. B. (2021). Perinatal depression: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(2), 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova, A. M. (2014). Maternal psychological state and infant’s temperament at three months. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 32(5), 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova, A. M., Cabini, L., Maturilli, F., Parenza, A., & Matthey, S. (2023a). Screening for perinatal distress in new fathers. In Proceedings XXIII national congress Italian psychological association clinical and dyamic section Florence, 15th–17th September 2023 (p. 26). Associazione Italiana di Psicologia. Available online: https://www.iris.unict.it/retrieve/93a9534f-7cab-4989-8738-8b89ead950d7/Proceedings%20XXIII%20National%20Congress%20AIP%202023.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Della Vedova, A. M., Santoniccolo, F., Sechi, C., & Trombetta, T. (2023b). Perinatal depression and anxiety symptoms, parental bonding and dyadic sensitivity in mother–baby interactions at three months post-partum. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earls, M. F., Yogman, M. W., Mattson, G., Rafferty, J., Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Baum, R., Gambon, T., Lavin, A., & Wissow, L. (2019). Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 143(1), e20183259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falah-Hassani, K., Shiri, R., & Dennis, C.-L. (2017). The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(12), 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, E. J., Fairbrother, N., Cox, M. L., White, I. R., & Fawcett, J. M. (2019). The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A multivariate bayesian meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(4), 18r12527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M. B. (2015). Structured clinical interview for the DSM (SCID). In R. L. Cautin, & S. O. Lilienfeld (Eds.), The encyclopedia of clinical psychology (1st ed., pp. 1–6). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerdingen, D., Crow, S., McGovern, P., Miner, M., & Center, B. (2009). Postpartum depression screening at well-child visits: Validity of a 2-question screen and the PHQ-9. The Annals of Family Medicine, 7(1), 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, S., & Lerner-Geva, L. (2019). Focus on fathers: Paternal depression in the perinatal period. Perspectives in Public Health, 139(4), 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guide for integration of perinatal mental health in maternal and child health services (1st ed.). (2022). World Health Organization.

- Gutierrez-Galve, L., Stein, A., Hanington, L., Heron, J., Lewis, G., O’Farrelly, C., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2019). Association of maternal and paternal depression in the postnatal period with offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(3), 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, B., Jarman, H., & Savage, S. (2004). The clinical application of three screening tools for recognizing post-partum depression. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 10(2), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, N. J. (2023). Mental health care in the perinatal period: Australian clinical practice guideline. Centre of Perinatal Excellence (COPE). Available online: https://www.cope.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/COPE_2023_Perinatal_Mental_Health_Practice_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hines, K. N., Mead, J., Pelletier, C.-A., Hanson, S., Lovato, J., & Quinn, K. H. (2018). The effect of hospitalization on mood in pregnancy [24E]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(1), 58S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2015). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 23.0). IBM Corp.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiferman, J. A., Farewell, C. V., Jewell, J., Lacy, R., Walls, J., Harnke, B., & Paulson, J. F. (2021). Anxiety among fathers during the prenatal and postpartum period: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 42(2), 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis-Jacques, A. F., Vamos, C., Torres, J., Dean, K., Hume, E., Obure, R., & Wilson, R. (2020). Bored, isolated and anxious: Experiences of prolonged hospitalization during high-risk pregnancy and preferences for improving care. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R., Adamson, J., & Gilbody, S. M. (2012). Diagnostic accuracy of case-finding questions to identify perinatal depression. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(8), E424–E430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masserdotti, E., Tessarin, S., Sofia Palmas, M., Capretti, M., Beretta, E., Sartori, E., & Simonetti, R. (2022). Esperienza preliminare finalizzata all’individuazione del disagio psicologico perinatale in donne a rischio ostetrico ricoverate nel reparto di Ostetricia. Psicologia della Salute, 3, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S., & Agostini, F. (2017). Using the edinburgh postnatal depression scale for women and men—Some cautionary thoughts. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 20(2), 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S., & Bilbao, F. (2018). A comparison of the PHQ-2 and MGMQ for screening for emotional health difficulties during pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S., & Della Vedova, A. M. (2018). A comparison of two measures to screen for emotional health difficulties during pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(5), 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S., & Della Vedova, A. M. (2020). Screening for mood difficulties in men in Italy and Australia using the edinburgh postnatal depression scale and the matthey generic mood questionnaire. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(2), 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S., Hariri, N., Razee, H., Casso-Vicarini, N., Fernandez, M., & Ensemble Pour La Petite Enfance. (2024). Validation du Matthey Generic Mood Questionnaire (MGMQ) pour dépister les difficultés émotionnelles chez les femmes en post-partum: Une validation pour les femmes arabophones. Devenir, 36(4), 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthey, S., Robinson, J., & Della Vedova, A. M. (2023). Women’s interpretation, understanding and attribution of the anhedonia question in the PHQ-4 and modified-Whooley questions in the antenatal period. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 41(3), 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S., & Ross-Hamid, C. (2011). The validity of DSM symptoms for depression and anxiety disorders during pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133(3), 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S., Souter, K., Valenti, B., & Ross-Hamid, C. (2019). Validation of the MGMQ in screening for emotional difficulties in women during pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 256, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S., Valenti, B., Souter, K., & Ross-Hamid, C. (2013). Comparison of four self-report measures and a generic mood question to screen for anxiety during pregnancy in English-speaking women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148(2–3), 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S., Ryan, E. G., Trevillion, K., Bick, D., Demilew, J., Milgrom, J., Pickles, A., & Howard, L. M. (2018). Prevalence and identification of anxiety disorders in pregnancy: The diagnostic accuracy of the two-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2). BMJ Open, 8(9), e023766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen-Scott, M., Fellmeth, G., Opondo, C., & Alderdice, F. (2022). Prevalence of perinatal anxiety in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M. W. (2024). Perinatal mental health. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of perinatal mental health disorders (1st ed., pp. 9–25). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, C., Garofoli, F., Tzialla, C., Orcesi, S., Spinillo, A., Politi, P., Balottin, U., Manzoni, P., & Stronati, M. (2014). Risk and protective factors in maternal–fetal attachment development. Early Human Development, 90, S45–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D. A. M., Middleton, M. M., Matthey, S., Goldfeld, P. S., Kemp, P. L., & Orsini, M. F. (2021). A comparison of two measures to screen for mental health symptoms in pregnancy and early postpartum: The Matthey generic mood questionnaire and the depression, anxiety, stress scales short-form. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, J. A. (1996). Qualitative descriptors of strength of association and effect size. Journal of Social Service Research, 21(4), 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook Smith, M., Cairns, L., Pullen, L. S. W., Opondo, C., Fellmeth, G., & Alderdice, F. (2022). Validated tools to identify common mental disorders in the perinatal period: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Journal of Affective Disorders, 298, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorti, M., Ginobbi, F., Simoncini, T., Pancetti, F., Carducci, A., Mauri, G., & Gemignani, A. (2023). Anxiety and depression in women hospitalized due to high-risk pregnancy: An integrative quantitative and qualitative study. Current Psychology, 42(7), 5570–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A., Pearson, R. M., Goodman, S. H., Rapa, E., Rahman, A., McCallum, M., Howard, L. M., & Pariante, C. M. (2014). Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1800–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2014). Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance guidelines. NICE Clinical Guideline CG192. Last Uploaded 2020. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Toscano, M., Royzer, R., Castillo, D., Li, D., & Poleshuck, E. (2021). Prevalence of depression or anxiety during antepartum hospitalizations for obstetric complications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 137(5), 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T. B., Davis, R. N., & Garfield, C. (2020). A call to action: Screening fathers for perinatal depression. Pediatrics, 145(1), e20191193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A., Koukab, A., Meraj, H., Dua, T., Chowdhary, N., Fatima, B., & Rahman, A. (2022). Screening programs for common maternal mental health disorders among perinatal women: Report of the systematic review of evidence. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whooley, M. A., Avins, A. L., Miranda, J., & Browner, W. S. (1997). Case-finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12(7), 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A., & Harris, M. G. (2017). A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Bai, Y., Li, X., Cheng, K. K., & Gong, W. (2024). Validation of the Chinese version of the Whooley questions for community screening of postpartum depression. Midwifery, 136, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych-Krekora, K., Sylwestrzak, O., Krekora, M., Oszukowski, P., Wachowska, K., Galecki, P., & Grzesiak, M. (2024). Assessment of emotions in pregnancy: Introduction of the Pregnancy Anxiety and Stress Rating Scale (PASRS) and its application in the context of hospitalization. Ginekologia Polska, 95, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Women (n = 221–228) * | Men (n = 48–55) * | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Age range (years) | 18–48 | 25–49 |

| (mean, SD) | (33.4; 2.8) | (35.3; 5.8) |

| Weeks pregnant | ||

| Weeks pregnant: Range | 4–40 | 12–40 |

| (% 1st trimester; 2nd trimester; 3rd trimester) | (3.6%; 19.2%; 77.2%) | (2%; 22%; 76%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/Partnered | 94% | 100% |

| Education level | ||

| Tertiary (university) | 43% | 35% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Italian | 81% | 94% |

| Other European | 13% | 6% |

| Non-European | 6% | 0% |

| Other children | ||

| No | 61% | 69% |

| Administration of measures | ||

| Face-to-face | 100% | 2% |

| Telephone | 0% | 67% |

| At home | 0% | 31% |

| Reasons for hospitalization | ||

| Risk of pre-term birth | 20.17% | n.a. |

| General health reasons | 22.80% | n.a. |

| Pregnancy complications | 51.75% | n.a. |

| Data missing | 5.26% | n.a. |

| Women (n = Varies per Question) | |

|---|---|

| Both measures | |

| % Satisfied with each measure (n = 195–197) | |

| MGMQ | 93% |

| Whooley/GAD-2 | 89% |

| Preference for the measures (n = 189) | |

| MGMQ preferred | 50% |

| Whooley/GAD-2 preferred | 37% |

| No preference | 13% |

| MGMQ measure | |

| Q1 Response options: Preference (n = 146) | |

| Only include ‘Yes/No’ | 32% |

| Also include ‘Possibly’ | 67% |

| Unsure (n = 1)/Missing (n = 1) | 1% |

| Q4 Response options: Preference (n = 146) | |

| Only include ‘Yes/No’ | 29% |

| Also include ‘Possibly’ | 71% |

| Q2 Impact Question (n = 123) | |

| Correct interpretation | 100% |

| Whooley Measure | |

| Anhedonia Question comprehension (n = 144) | |

| Interpreted incorrectly | 3% (n = 4) |

| Had difficulty understanding it | <1% (n = 1) |

| Attribution of endorsed Anhedonia Question (n = 17) | |

| Just due to physical changes | 47% (n = 8) |

| Includes due to mood or worries | 53% (n = 9) |

| Women (n = 227–228) | Men * (n = 53–55) | |

|---|---|---|

| Measures: % screening positive | ||

| Whooley/GAD-2 1 | 35.5% (+/−5%) | 20.0% (+/−8.8%) |

| Whooley 2 | 31.6% (+/−4.9%) | 12.7% (+/−7.3%) |

| GAD-2 3 | 15.8% (+/−3.8%) | 10.9% (+/−6.9%) |

| Positive on both the Whooley&GAD-2 | 11.8% (+/−3.4%) | 3.6% (n = 2) |

| MGMQ | ||

| Minor or Mod/Major distress | 33.9% (+/−5%) | 15.1% (+/−7.9%) |

| Minor distress 4 | 7.0% (+/−2.7%) | 1.9% (n = 1) |

| Moderate/Major distress 5 | 26.9% (+/−4.7%) | 13.2% (+/−7.5%) |

| MGMQ Q2: % Bothered | ||

| Moderately | 19.8% (+/−4.2%) | 11.3% (+/−7.0%) |

| A lot | 4.0% (+/−2.1%) | 1.9% (n = 1) |

| A little + ‘Possibly’ on Q4 | 7.0% (+/−2.7%) | 1.9% (n = 1) |

| MGMQ Q4: % Wish-to-talk with a health professional | ||

| Yes | 7.5% (+/−2.8%) | 0% |

| Possibly | 16.2% (+/−3.9%) | 3.8% (n = 2) |

| No | 36.0% (+/−5.1%) | 30.2% (+/−10.1%) |

| Not applicable a | 39.9% (+/−5.2%) | 58.5% (+/−10.9%) |

| Missing: | n = 1 | 0% |

| Screening Outcomes (Positive/Negative) | Positive Whooley/GAD-2 1 f (%) | Negative Whooley/GAD-2 f (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive MGMQ 2 | 53 (68.8%) | 24 (31,2%) | 77 (33.77%) |

| Negative MGMQ | 28 (18.54%) | 123 (81.46%) | 151 (66.23%) |

| Total | 81 (35.52%) | 147 (64.48%) | 228 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Della Vedova, A.M.; Bani, C.; Capretti, M.; Lucariello, S.; Simonetti, R.; Pelamatti, S.; Beretta, E. Screening Hospitalized Pregnant Women and Their Male Partners for Possible Distress: A Comparison of the Clinical Usefulness of Two Screening Measures. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060767

Della Vedova AM, Bani C, Capretti M, Lucariello S, Simonetti R, Pelamatti S, Beretta E. Screening Hospitalized Pregnant Women and Their Male Partners for Possible Distress: A Comparison of the Clinical Usefulness of Two Screening Measures. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):767. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060767

Chicago/Turabian StyleDella Vedova, Anna Maria, Chiara Bani, Margherita Capretti, Silvia Lucariello, Rita Simonetti, Serena Pelamatti, and Emanuela Beretta. 2025. "Screening Hospitalized Pregnant Women and Their Male Partners for Possible Distress: A Comparison of the Clinical Usefulness of Two Screening Measures" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060767

APA StyleDella Vedova, A. M., Bani, C., Capretti, M., Lucariello, S., Simonetti, R., Pelamatti, S., & Beretta, E. (2025). Screening Hospitalized Pregnant Women and Their Male Partners for Possible Distress: A Comparison of the Clinical Usefulness of Two Screening Measures. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060767