Adaptation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure to Turkish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Translation of the CARE Measure into Turkish

2.2. Study Setting and Sampling

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Questionnaire

2.3.2. The Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Weaknesses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CARE | Consultation and Relational Empathy |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition |

| CVI | Content validity index |

| KMO | Keiser–Meyer–Olkin coefficient |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square of Error Approximation |

| NNFI | Non-Normed Fit Index |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aomatsu, M., Abe, H., Abe, K., Yasui, H., Suzuki, T., Sato, J., Ban, N., & Mercer, S. W. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the CARE Measure in a general medicine outpatient setting. Family Practice, 31(1), 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckman, H. B., Markakis, K. M., Suchman, A. L., & Frankel, R. M. (1994). The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice: Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Archives of Internal Medicine, 154(12), 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassany, O., Boureau, F., Liard, F., Bertin, P., Serrie, A., Ferran, P., Keddad, K., Jolivet-Landreau, I., Marchand, S., & Pouzet, C. (2006). Effects of training on general practitioners’ management of pain in osteoarthritis: A randomized multicenter study. Journal of Rheumatology, 33(9), 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis (2nd ed., p. 217). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Crosta Ahlforn, K., Bojner Horwitz, E., & Osika, W. (2017). A Swedish version of the consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 35(3), 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambha-Miller, H., Feldman, A. L., Kinmonth, A. L., & Griffin, S. J. (2019). Association between primary care practitioner empathy and risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes: A population-based prospective cohort study. Annals of Family Medicine, 17(4), 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J. (2020). Empathy in medicine: What it is, and how much we really need it. The American Journal of Medicine, 133(5), 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J., & Fotopoulou, A. (2015). Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: Unifying theories. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empati TDK Sözlük Anlamı. (2024). Available online: https://sozluk.gov.tr/ (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Erkorkmaz, Ü., EtİKan, İ., DemİR, O., ÖZdamar, K., & SanİSoĞLu, S. Y. (2013). Confirmatory factor analysis and fit indices: Review. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences, 33(1), 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C. S. C., Hua, A., Tam, L., & Mercer, S. W. (2009). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the CARE Measure in a primary care setting in Hong Kong. Family Practice, 26(5), 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Del Barrio, L., Rodríguez-Díez, C., Martín-Lanas, R., Costa, P., Costa, M. J., & Díez, N. (2021). Reliability and validity of the Spanish (Spain) version of the consultation and relational empathy measure in primary care. Family Practice, 38(3), 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R. L. (2014). Factor analysis. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gönüllü, İ., & Öztuna, D. (2015). Jefferson doktor empati ölçeği öğrenci versiyonunun Türkçe adaptasyonu. Marmara Medical Journal, 25(2), 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hanževački, M., Jakovina, T., Bajić, Ž., Tomac, A., & Mercer, S. (2015). Reliability and validity of the croatian version of consultation and relational empathy (CARE) Measure in primary care setting. Croatian Medical Journal, 56(1), 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M., Louis, D. Z., Markham, F. W., Wender, R., Rabinowitz, C., & Gonnella, J. S. (2011). Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Academic Medicine, 86(3), 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, G. C., Gotto, J. L., Mangione, S., West, S., & Hojat, M. (2007). Jefferson scale of patient’s perceptions of physician empathy: Preliminary psychometric data. Croatian Medical Journal, 48(1), 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, W., Roter, D. L., Mullooly, J. P., Dull, V. T., & Frankel, R. M. (1997). Physician-patient communication: The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA, 277(7), 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P., White, P., Kelly, J., Everitt, H., & Mercer, S. (2015). Randomised controlled trial of a brief intervention targeting predominantly non-verbal communication in general practice consultations. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 65(635), e351–e356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, A. C. T., Fagundes, F. R. C., Fuhro, F. F., & Cabral, C. M. N. (2019). Translation, cross-cultural adaptation to brazilian portuguese, and analysis of measurement properties of the consultation and relational empathy measure. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 18(2), 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markakis, K., Frankel, R., Beckman, H., & Suchman, A. (1999, April 29–May 1). Teaching empathy: It can be done. Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, S. W. (2004). The consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: Development and preliminary validation and reliability of an empathy-based consultation process measure. Family Practice, 21(6), 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. W., McConnachie, A., Maxwell, M., Heaney, D., & Watt, G. C. M. (2005). Relevance and practical use of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Family Practice, 22(3), 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. W., & Murphy, D. J. (2008). Validity and reliability of the CARE measure in secondary care. Clinical Governance: An International Journal, 13(4), 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. W., & Reynolds, W. J. (2002). Empathy and quality of care. The British Journal of General Practice, 52, S9–S12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montag, C., Gallinat, J., & Heinz, A. (2008). Theodor Lipps and the concept of empathy: 1851–1914. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(10), 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natali, F., Corradini, L., Sconza, C., Taylor, P., Furlan, R., Mercer, S. W., & Gatti, R. (2022). Development of the Italian version of the consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure: Translation, internal reliability, and construct validity in patients undergoing rehabilitation after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Disability and Rehabilitation, 45, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-Y., Shin, J., Park, H.-K., Kim, Y. M., Hwang, S. Y., Shin, J.-H., Heo, R., Ryu, S., & Mercer, S. W. (2022). Validity and reliability of a Korean version of the consultation and relational empathy (CARE) measure. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R. (2009). Empirical research on empathy in medicine—A critical review. Patient Education and Counseling, 76(3), 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S., Kumar, A., Puranik, M., & Shanbhag, N. (2020). Exploring the educational opportunity and implementation of CARE among dental students in India. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9(1), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakel, D. P., Hoeft, T. J., Barrett, B. P., Chewning, B. A., Craig, B. M., & Niu, M. (2009). Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Family Medicine, 41(7), 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, W. J., & Scott, B. (1999). Empathy: A crucial component of the helping relationship. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 6(5), 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. D., Kellar, J., Walters, E. L., Reibling, E. T., Phan, T., & Green, S. M. (2016). Does emergency physician empathy reduce thoughts of litigation? A randomised trial. Emergency Medicine Journal, 33(8), 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltner, C., Giquello, J. A., Monrigal-Martin, C., & Beydon, L. (2011). Continuous care and empathic anaesthesiologist attitude in the preoperative period: Impact on patient anxiety and satisfaction. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 106(5), 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. W. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorndike, R. M. (1995). Book review: Psychometric theory (3rd ed.) by Jum Nunnally and Ira Bernstein New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994, xxiv + 752 pp. Applied Psychological Measurement, 19(3), 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, I., Scholten Meilink Lenferink, N., Lucassen, P. L. B. J., Mercer, S. W., van Weel, C., Olde Hartman, T. C., & Speckens, A. E. M. (2017). Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the consultation and relational empathy measure in primary care. Family Practice, 34(1), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wensing, M., Jung, H. P., Mainz, J., Olesen, F., & Grol, R. (1998). A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: Description of the research domain. Social Science & Medicine, 47(10), 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 176 (58.7%) |

| Male | 124 (41.3%) | |

| Age | 18–30 | 88 (29.3%) |

| 31–43 | 109 (36.4%) | |

| 44–56 | 54 (18.0%) | |

| 57 and over | 49 (16.3%) | |

| Civil status | Single | 83 (27.7%) |

| Married | 197 (65.7%) | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 20 (6.6%) | |

| Education | Primary and lower | 23 (7.6%) |

| Middle School | 32 (10.7%) | |

| High school | 80 (26.7%) | |

| University or higher | 165 (55.0%) | |

| Income Level | Low | 54 (18.0%) |

| Average | 230 (76.7%) | |

| High | 16 (5.3%) | |

| Examination frequency * | Once a year or less | 56 (18.7%) |

| 2–6 times a year | 144 (48.0%) | |

| 7–12 times a year | 49 (16.3%) | |

| 13 times a year or more often | 51 (17.0%) | |

| Presence of chronic disease * | Yes | 121 (40.3%) |

| No | 179 (59.7%) | |

| Number of people in household * | 1–4 people | 244 (81.3%) |

| 5–10 people | 56 (18.7%) | |

| Care Measure Questions | Poor | Fair | Good | Very Good | Excellent | Not Answered or Missing | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Did you feel comfortable? | 7 (2.3%) | 39 (13.0%) | 101 (33.7%) | 81 (27.0%) | 72 (24.0%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 2-Were you given a chance to relate your story? | 5 (1.7%) | 26 (8.7%) | 90 (30.0%) | 93 (31.0%) | 86 (28.7%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 3-Did they really listen to you? | 12 (4.0%) | 32 (10.7%) | 81 (27.0%) | 96 (32.0%) | 79 (26.3%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 4-Did they show a holistic interest in you? | 13 (4.3%) | 39 (13.0%) | 76 (25.3%) | 86 (28.7%) | 86 (28.7%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 5-Did they fully understand your concerns? | 18 (6.0%) | 39 (13.0%) | 74 (24.7%) | 91 (30.3%) | 78 (26.0%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 6-Did they show you interest and compassion? | 23 (7.7%) | 39 (13.0%) | 78 (26.0%) | 89 (29.7%) | 71 (23.7%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 7-Did they have a positive approach towards you? | 9 (3.0%) | 31 (10.3%) | 76 (25.3%) | 99 (33.0%) | 85 (28.3%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 8-Were their explanations clear? | 13 (4.3%) | 35 (11.7%) | 71 (23.7%) | 90 (30.0%) | 91 (30.3%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 9-Did they help you arrange for a follow-up appointment? | 13 (4.3%) | 30 (10.0%) | 75 (25.0%) | 96 (32.0%) | 86 (28.7%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| 10-Did they set up an action plan with you? | 16 (5.3%) | 38 (12.7%) | 74 (24.7%) | 85 (28.3%) | 87 (29.0%) | 0 | 300 (100%) |

| Corrected Item–Total Correlation If Item Deleted | Cronbach’s α If Item Deleted | McDonald’s ω If Item Deleted | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0.817 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.931 |

| C2 | 0.838 | 0.971 | 0.971 | 0.911 |

| C3 | 0.870 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.907 |

| C4 | 0.893 | 0.969 | 0.970 | 0.897 |

| C5 | 0.917 | 0.968 | 0.969 | 0.890 |

| C6 | 0.884 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.884 |

| C7 | 0.898 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.883 |

| C8 | 0.877 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.867 |

| C9 | 0.870 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.850 |

| C10 | 0.855 | 0.971 | 0.971 | 0.829 |

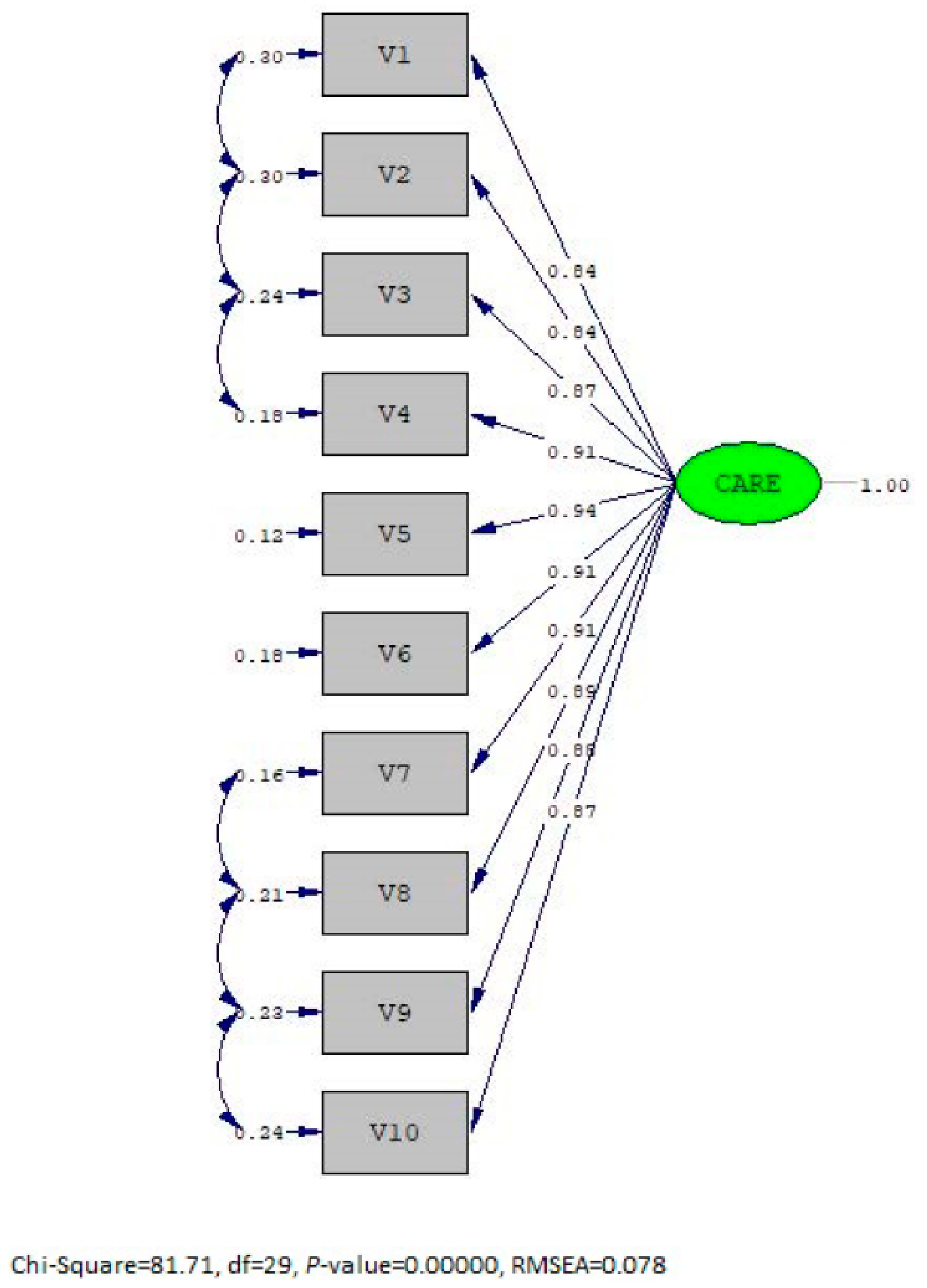

| χ2 | SD | χ2/SD | RMSEA | CFI | NFI | NNFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 81.71 | 29 | 2.82 | 0.078 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erzurumlu, M.; Özçelik, H.; Akdeniz, M.; Kavukçu, E.; Avcı, H.H. Adaptation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure to Turkish. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060721

Erzurumlu M, Özçelik H, Akdeniz M, Kavukçu E, Avcı HH. Adaptation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure to Turkish. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):721. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060721

Chicago/Turabian StyleErzurumlu, Murat, Habibe Özçelik, Melahat Akdeniz, Ethem Kavukçu, and Hasan H. Avcı. 2025. "Adaptation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure to Turkish" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060721

APA StyleErzurumlu, M., Özçelik, H., Akdeniz, M., Kavukçu, E., & Avcı, H. H. (2025). Adaptation of the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure to Turkish. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060721