The Effect of Impartial Beneficence on Bystander Cooperation Behavior: The Roles of Social Perception and Impartial Beneficence Personality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Experimental Design

2.1.3. Experimental Materials and Tools

2.1.4. Experimental Procedure

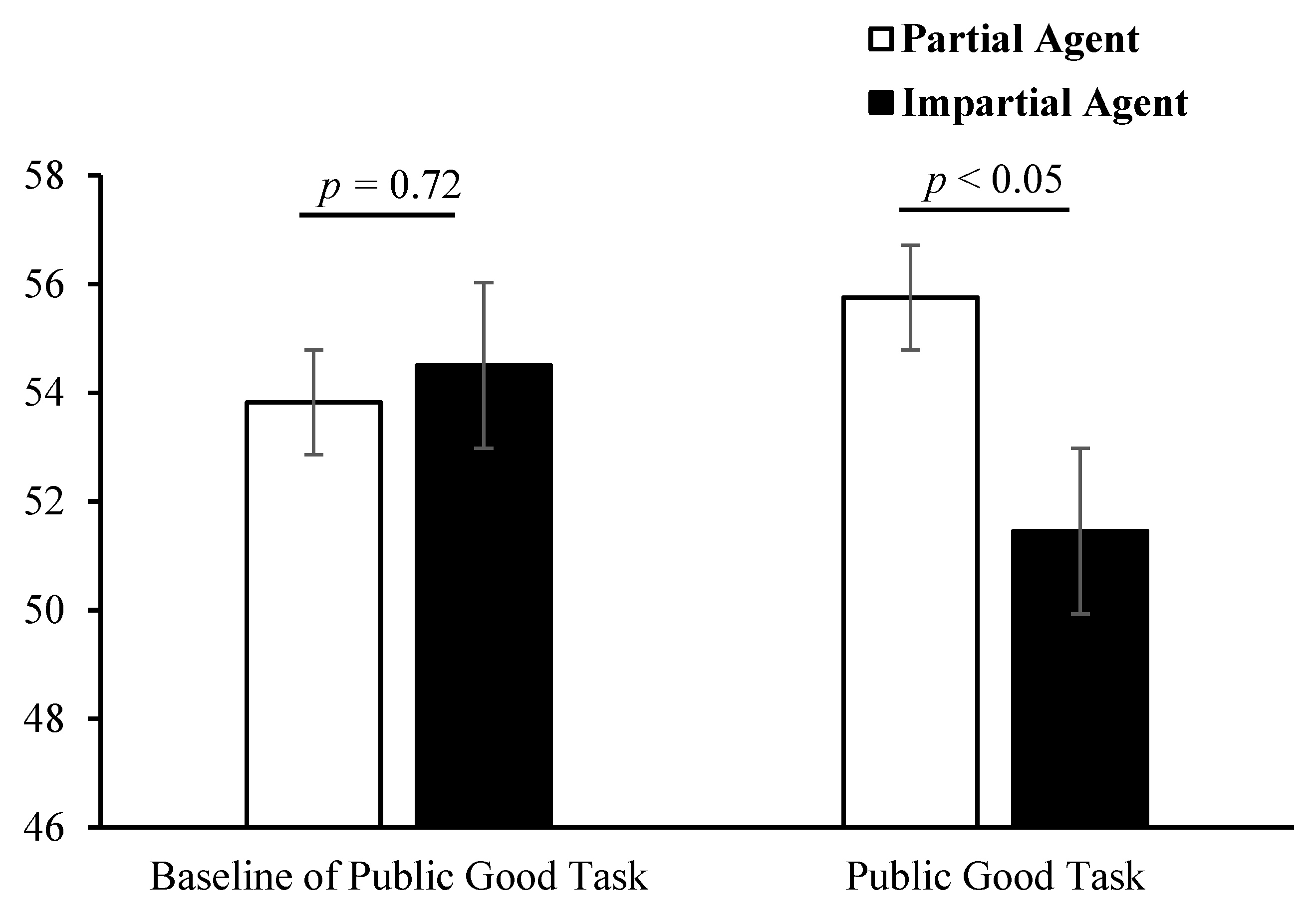

2.2. Results

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Experimental Materials and Tools

3.1.3. Experimental Procedure

3.2. Results

4. Experiment 3

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Experimental Materials and Tools

4.1.3. Experimental Procedure

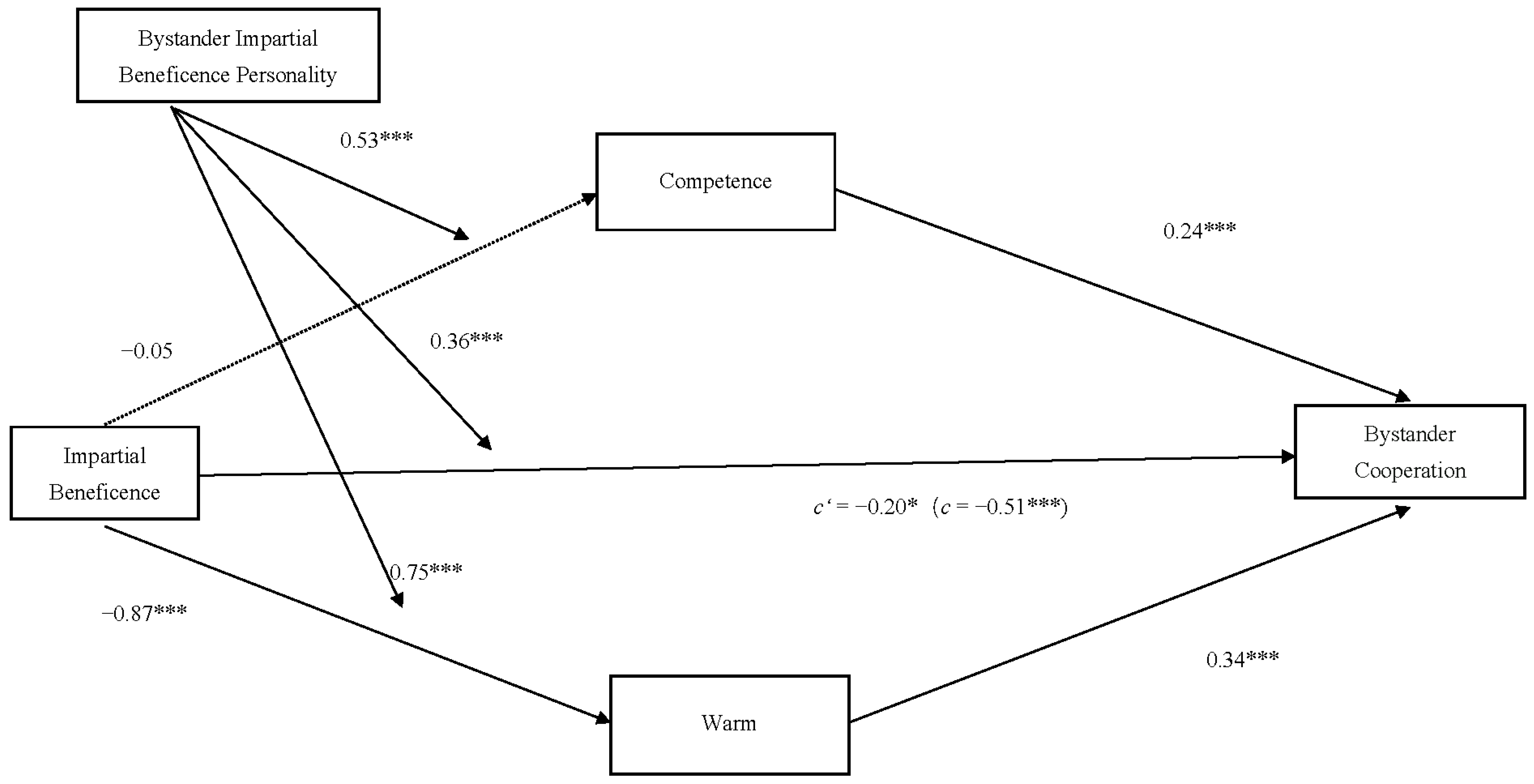

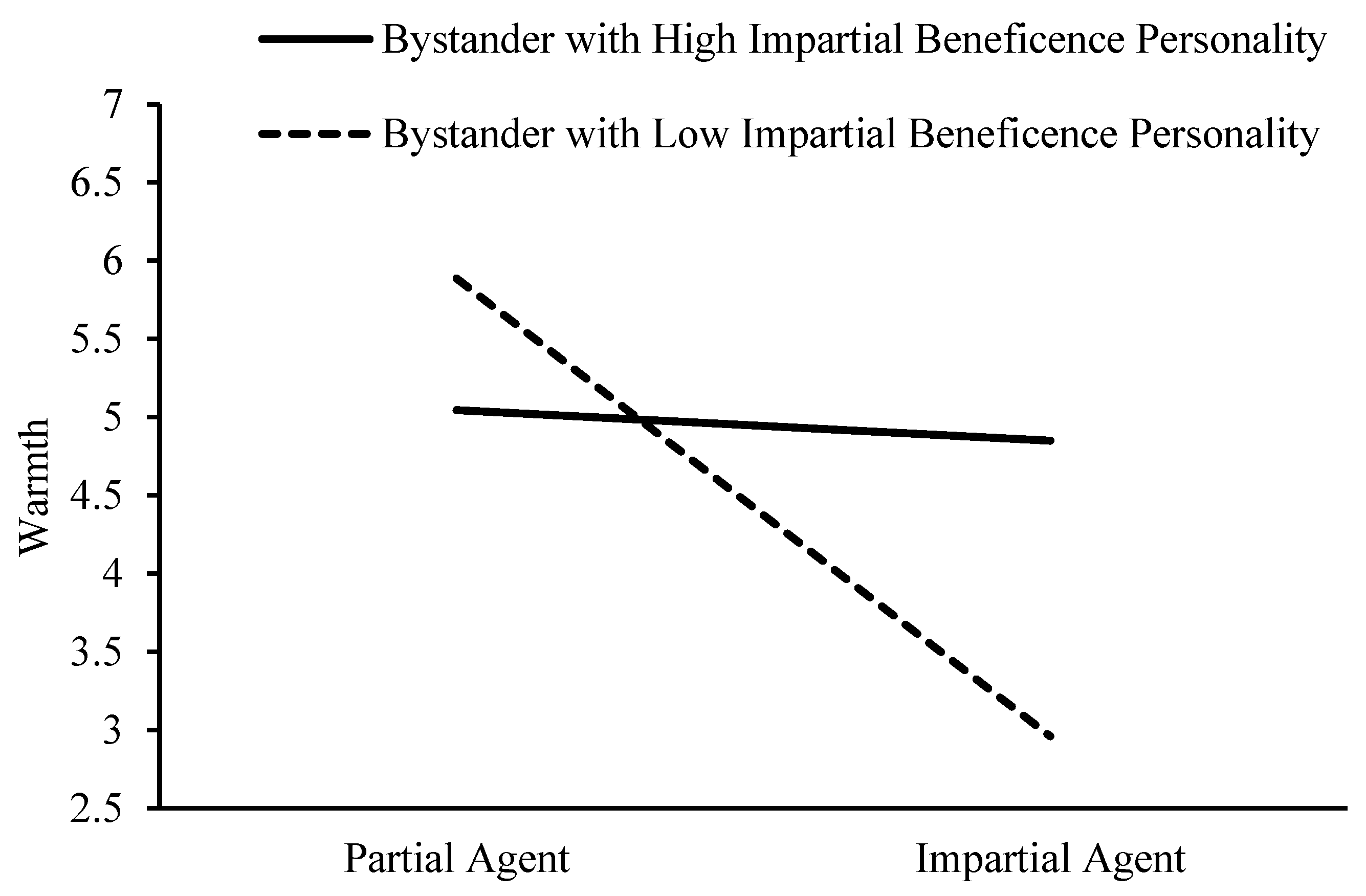

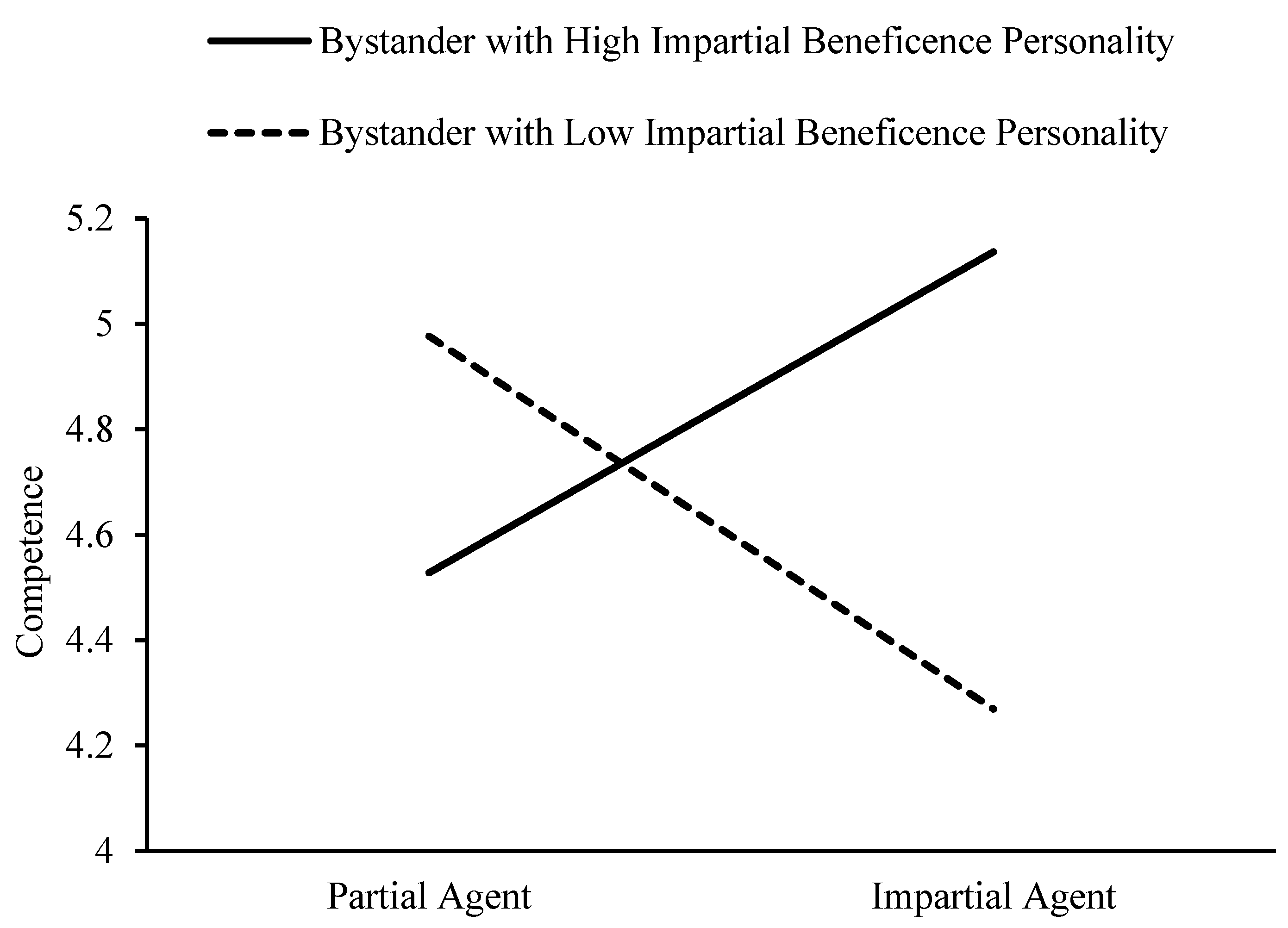

4.2. Results

5. General Discussion

5.1. How Social Perception Acts as a Mediator

5.2. How Impartial Beneficence Personality Influences the Aftereffects of Impartial Beneficence Utilitarian

5.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.3.1. Theoretical Implications

5.3.2. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2007). Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, E., Dsouza, S., Kim, R., Schulz, J., Henrich, J., Shariff, A., Bonnefon, J., & Rahwan, I. (2018). The Moral Machine experiment. Nature, 563(7729), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, M. D., Baumert, A., Denissen, J. J. A., Hartung, F., Penke, L., Schmukle, S. C., Schönbrodt, F. D., Schröder-Abé, M., Vollmann, M., Wagner, J., & Wrzus, C. (2011). PERSOC: A unified framework for understanding the dynamic interplay of personality and social relationships. European Journal of Personality, 25(2), 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, B., Kovacs, M., Protzko, J., Nagy, T., Kekecs, Z., Palfi, B., Adamkovic, M., Adamus, S., Albalooshi, S., Albayrak-Aydemir, N., Alfian, I. N., Alper, S., Alvarez-Solas, S., Alves, S. G., Amaya, S., Andresen, P. K., Anjum, G., Ansari, D., Arriaga, P., … Aczel, B. (2022). Situational factors shape moral judgements in the trolley dilemma in Eastern, Southern and Western countries in a culturally diverse sample. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(6), 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, P. (2016). Biological markets and the effects of partner choice on cooperation and friendship. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, D. M., & Pizarro, D. A. (2011). The mismeasure of morals: Antisocial personality traits predict utilitarian responses to moral dilemmas. Cognition, 121(1), 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumard, N., André, J., & Sperber, D. (2013). A mutualistic approach to morality: The evolution of fairness by partner choice. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(1), 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentham, J. (1983). The collected works of Jeremy Bentham: Deontology, together with a table of the springs of action; and the article on utilitarianism. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, J. Z., Barasch, A., Levine, E. E., & Small, D. A. (2018). Impediments to effective altruism: The role of subjective preferences in charitable giving. Psychological Science, 29(5), 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostyn, D. H., & Roets, A. (2017). Trust, trolleys and social dilemmas: A replication study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(5), e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, O. S. (2016). Morality as cooperation: A problem-centred approach. In T. K. Shackelford, & R. D. Hansen (Eds.), The evolution of morality; The evolution of morality (pp. 27–51, 323p). Springer International Publishing AG. Chapter xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, O. S., Jones Chesters, M., & Van Lissa, C. J. (2019). Mapping morality with a compass: Testing the theory of ‘morality-as-cooperation’ with a new questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lazari-Radek, K., & Singer, P. (2017). Utilitarianism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbruch, A. B., & Krasnow, M. M. (2022). Why warmth matters more than competence: A new evolutionary approach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(6), 1604–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, J. A. C., Faber, N. S., Savulescu, J., & Crockett, M. J. (2018). The costs of being consequentialist: Social inference from instrumental harm and impartial beneficence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, J. A. C., Pizarro, D. A., & Crockett, M. J. (2016). Inference of trustworthiness from intuitive moral judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(6), 772–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J., Meindl, P., Beall, E., Johnson, K. M., & Zhang, L. (2016). Cultural differences in moral judgment and behavior, across and within societies. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J. (2009). The application and development of stereotype content model and system model. Advances in Psychological Science, 17(4), 845–851. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. S. (2017). In a moral dilemma, choose the one you love: Impartial actors are seen as less moral than partial ones. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(3), 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, G., Everett, J. A. C., Earp, B. D., Caviola, L., Faber, N. S., Crockett, M. J., & Savulescu, J. (2018). Beyond sacrificial harm: A two-dimensional model of utilitarian psychology. Psychological Review, 125(2), 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, G., Everett, J. A. C., Earp, B. D., Farias, M., & Savulescu, J. (2015). ‘Utilitarian’ judgments in sacrificial moral dilemmas do not reflect impartial concern for the greater good. Cognition, 134, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Holyoak, K. J. (2020). “But he’s my brother”: The impact of family obligation on moral judgments and decisions. Memory & Cognition, 48(1), 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J., Wynn, K., & Bloom, P. (2020). Do children and adults take social relationship into account when evaluating people’s actions? Child Development, 91(5), e1082–e1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navajas, J., Heduan, F. A., Garbulsky, G., Tagliazucchi, E., Ariely, D., & Sigman, M. (2021). Moral responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Royal Society Open Science, 8, 210096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J., Shin, Y., Kim, S., Maeng, S., & Ihm, J. (2023). Effects of perspective switching and utilitarian thinking on moral judgments in a sacrificial dilemma among healthcare and non-healthcare students. Current Psychology, 43, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, T. S., & Fiske, A. P. (2011). Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychological Review, 118(1), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauthmann, J. F. (Ed.). (2021). The handbook of personality dynamics and processes. Elsevier Academic Press. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/books/handbook-personality-dynamics-processes/docview/2628325611/se-2 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rhodes, M., & Chalik, L. (2013). Social categories as markers of intrinsic interpersonal obligations. Psychological Science, 24(6), 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, S. C., Weiss, A., & Conway, P. (2017). Judging those who judge: Perceivers infer the roles of affect and cognition underpinning others’ moral dilemma responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffler, S. (2010). Morality and reasonable partiality. In B. Feltman, & J. Cottingham (Eds.), Partiality and impartiality: Morality, special relationships, and the wider world (pp. 98–130). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, A., Kanakogi, Y., & Myowa, M. (2019). Strategic reputation management: Children adjust their reward distribution in accordance with an observer’s mental state. Cognitive Development, 50, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smillie, L. D., Katic, M., & Laham, S. M. (2021). Personality and moral judgment: Curious consequentialists and polite deontologists. Journal of Personality, 89(3), 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellar, J. E., & Willer, R. (2018). Unethical and inept? The influence of moral information on perceptions of competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(2), 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H., Li, X., Wei, Y., Li, X., Chen, L., & Zhang, Y. (2022). The impact of partner choice on cooperative behavior and its mechanism. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(10), 2356–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciszke, B., & Abele, A. E. (2008). The primacy of communion over agency and its reversals in evaluations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(7), 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Partial Agent | Impartial Agent | |

|---|---|---|

| Zhang Li is a firefighter attempting to rescue individuals from a burning building on the verge of collapse. In the limited time remaining, he can save only one more person. Upon entering a room, Zhang Li finds two trapped individuals whom he immediately recognizes. One is a renowned peace negotiator celebrated for resolving armed conflicts globally; his survival would enable him to continue this vital work, potentially saving many more lives. The other individual is Zhang Li’s mother. Zhang Li faces a critical decision: he must choose whom to save, knowing that the one he does not save will perish. | One of the three partners, Partner A, in the decision-making game believes that Zhang Li should prioritize saving his mother over the famous peace negotiator. A’s rationale is, “I think Zhang Li should save his mother to ensure her survival. Although I recognize that rescuing the peace negotiator has the potential to save more lives, I believe that honoring Zhang Li’s responsibility to his mother holds greater significance.” | One of the three partners, Partner A, in the decision-making game believes that Zhang Li should save the famous peace negotiator rather than his mother. A’s rationale is, “I think Zhang Li should rescue the famous peace negotiator because doing so could potentially save more lives, which I consider to be more important than any duty he owes to his mother.” |

| Partial Agent | Impartial Agent | |

|---|---|---|

| Zhang Li is a firefighter attempting to rescue individuals from a burning building on the verge of collapse. In the limited time remaining, he can save only one more person. Upon entering a room, Zhang Li finds two trapped individuals whom he immediately recognizes. One is a renowned peace negotiator celebrated for resolving armed conflicts globally; his survival would enable him to continue this vital work, potentially saving many more lives. The other individual is Zhang Li’s mother. Zhang Li faces a critical decision: he must choose whom to save, knowing that the one he does not save will perish. | Person A, your partner, believes that Zhang Li should prioritize saving his mother over the famous peace negotiator. A’s rationale is, “I think Zhang Li should save his mother to ensure her survival. Although I recognize that rescuing the peace negotiator has the potential to save more lives, I believe that honoring Zhang Li’s responsibility to his mother holds greater significance.” | Person A, your partner, believes that Zhang Li should save the famous peace negotiator rather than his mother. A’s rationale is, “I think Zhang Li should rescue the famous peace negotiator because doing so could potentially save more lives, which I consider to be more important than any duty he owes to his mother.” |

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral Judgment | 0.5 ± 0.5 | |||||||

| Warm | 4.63 ± 1.70 | −0.51 *** | ||||||

| Competence | 4.68 ± 1.24 | −0.07 | 0.32 *** | |||||

| Trust Task | 5.27 ± 2.97 | −0.30 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.34 *** | ||||

| Sex | 0.33 ± 0.47 | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.11 * | |||

| Age | 30.73 ± 14.75 | −0.04 | 0.15 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.09 | 0.15 ** | ||

| Subjective Social Class | 5.35 ± 1.41 | 0.001 | 0.19 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.15 ** | 0.09 | 0.17 *** | |

| Baseline of Trust Task | 5.74 ± 2.81 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.11 * | 0.46 *** | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.14 ** |

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impartial Beneficence | 0.5 ± 0.5 | ||||||||

| Warm | 4.72 ± 1.81 | −0.43 *** | |||||||

| Competence | 4.74 ± 1.22 | −0.02 | 0.48 *** | ||||||

| Trust Task | 5.92 ± 2.85 | −0.23 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.49 *** | |||||

| Sex | 0.35 ± 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.005 | ||||

| Age | 29.75 ± 8.12 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.11 * | 0.13 ** | 0.06 | |||

| Subjective Social Class | 5.56 ± 1.49 | 0.01 | −0.093 * | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.16 ** | ||

| Baseline of Trust Task | 6.31 ± 2.58 | 0.05 | −0.001 | 0.11 * | 0.35 *** | 0.05 | 0.14 ** | −0.15 ** | |

| Impartial Beneficence Personality | 3.47 ± 1.27 | 0.05 | 0.15 ** | 0.10 * | 0.16 ** | −0.04 | 0.10 * | 0.03 | 0.10 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Y. The Effect of Impartial Beneficence on Bystander Cooperation Behavior: The Roles of Social Perception and Impartial Beneficence Personality. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060718

Xu X, Zhang Y, Yu M, Li H, Zhang F, Xu Y. The Effect of Impartial Beneficence on Bystander Cooperation Behavior: The Roles of Social Perception and Impartial Beneficence Personality. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060718

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiaodan, Yingjun Zhang, Ming Yu, Hongju Li, Feng Zhang, and Yan Xu. 2025. "The Effect of Impartial Beneficence on Bystander Cooperation Behavior: The Roles of Social Perception and Impartial Beneficence Personality" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060718

APA StyleXu, X., Zhang, Y., Yu, M., Li, H., Zhang, F., & Xu, Y. (2025). The Effect of Impartial Beneficence on Bystander Cooperation Behavior: The Roles of Social Perception and Impartial Beneficence Personality. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 718. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060718