Maternal Intrusive Thoughts and Dissociative Experiences in the Context of Early Caregiving Under Varying Levels of Societal Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

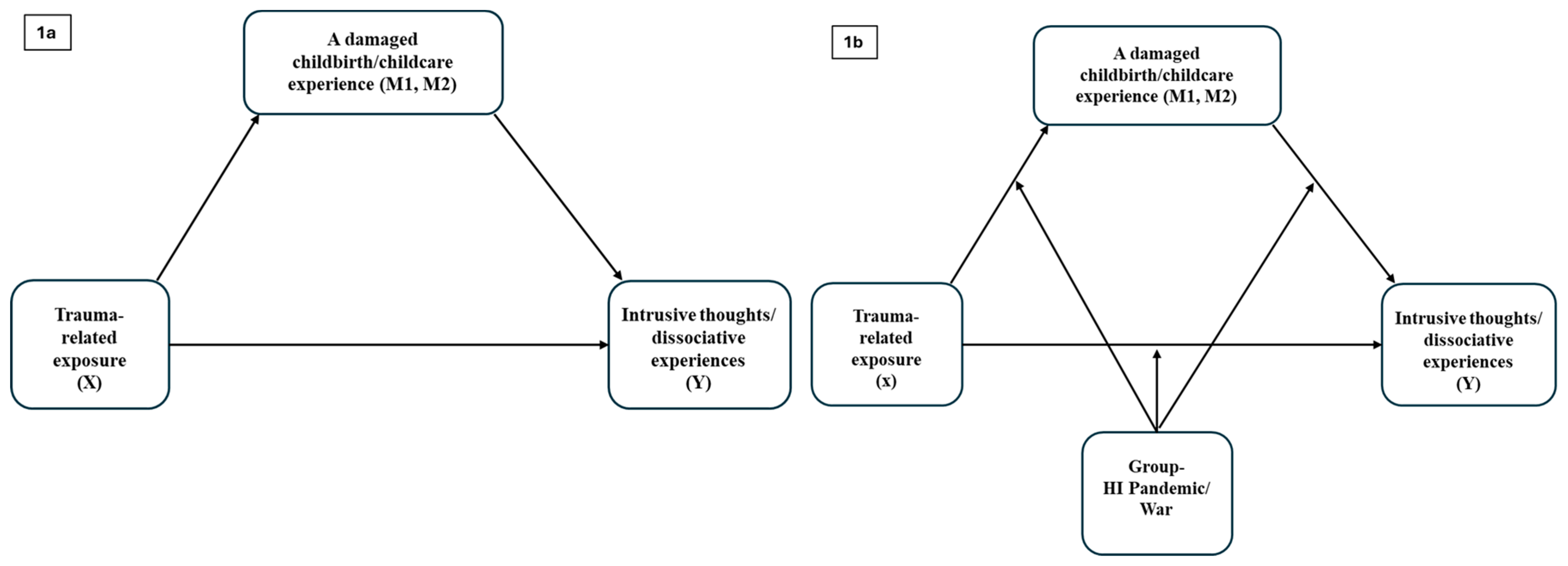

1.1. Current Investigation

1.2. Part 1

1.3. Part 2

- RQ1. Are there differences in crisis exposure levels and a damaged experience of childbirth and childcare between the high-intensity pandemic and war groups?

- RQ2. Does the type of crisis (high-intensity pandemic or war) moderate the mediation effect between crisis exposure and maternal disintegrative responses?

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.1.1. Study Design

2.1.2. Setting

2.1.3. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Maternal Disintegrative Responses Scale

2.3.2. Trauma-Related Exposure

2.3.3. Damaged Experiences of Childbirth and Childcare

2.3.4. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

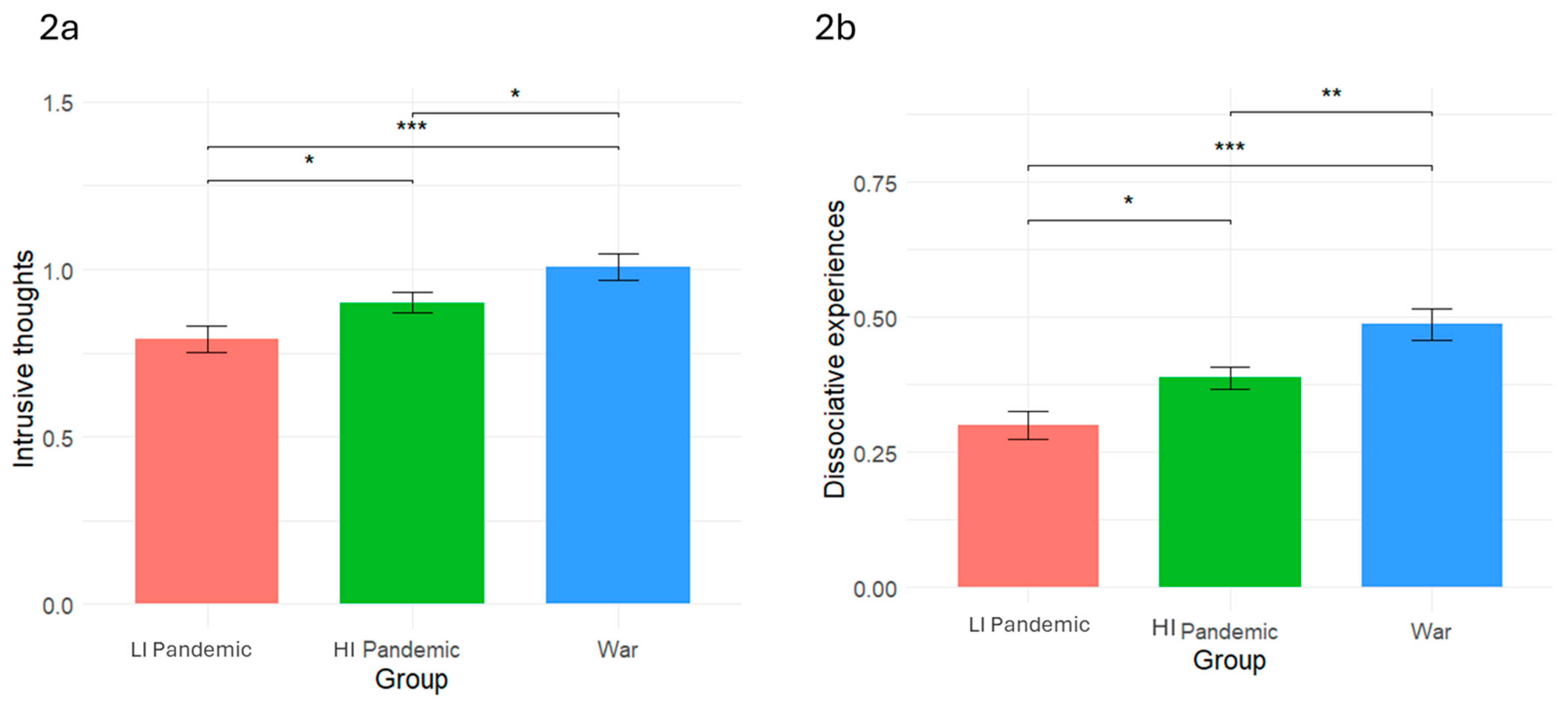

3.1. Part 1: Differences in Disintegrative Responses as a Function of Context

3.1.1. Bivariate Correlations Between the Demographic Variables and Disintegrative Responses

3.1.2. Differences in Disintegrative Responses by Period Group

3.2. Part 2: Examining Trauma Exposure, Damaged Experience of Childbirth and Childcare, and Disintegrative Responses in the High-Intensity Pandemic and War Contexts

3.2.1. Differences in Trauma Exposure and Damaged Experience of Childbirth and Childcare Between the High-Intensity Pandemic and War Groups

3.2.2. Bivariate Correlations Between Trauma Exposure, Damaged Experience of Childbirth and Childcare, and Disintegrative Responses

3.2.3. Mediation Models

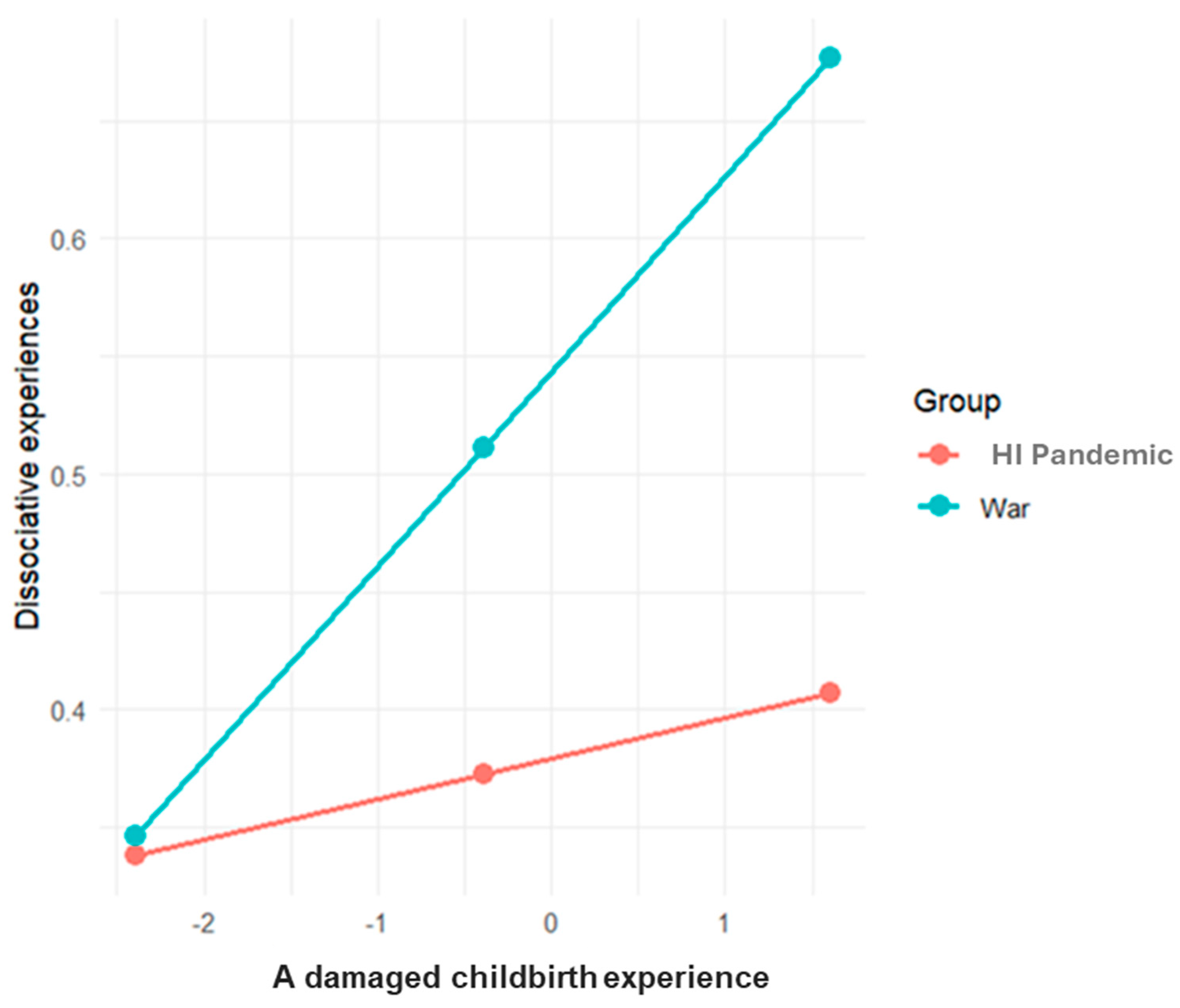

3.2.4. Moderated Mediation Models

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Altig, D., Baker, S., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, S., Davis, S. J., Leather, J., Meyer, B., Mihaylov, E., Mizen, P., Parker, N., Renault, T., Smietanka, P., & Thwaites, G. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M. R., Salisbury, A. L., Uebelacker, L. A., Abrantes, A. M., & Battle, C. L. (2022). Stress, coping and silver linings: How depressed perinatal women experienced the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 298, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleyard, K., & Osofsky, J. D. (2003). Parenting after trauma: Supporting parents and caregivers in the treatment of children impacted by violence. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(2), 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, G. B., Riggan, K. A., Huang, L., Torbenson, V. E., Long, M. E., Wick, M. J., Allyse, M. A., & Rivera-Chiauzzi, E. Y. (2022). “I had so many life-changing decisions I had to make without support”: A qualitative analysis of women’s pregnant and postpartum experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1), 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M. S., Chan, S. J., Ein-Dor, T., & Dekel, S. (2022). Traumatic childbirth during COVID-19 triggers maternal psychological growth and in turn better mother-infant bonding. Journal of Affective Disorders, 313, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, B., Crown, C. L., Jasnow, M., Sossin, K. M., Kaitz, M., Margolis, A., & Lee, S. H. (2023). The vocal dialogue in 9/11 pregnant widows and their infants: Specificities of co-regulation. Infant Behavior and Development, 70, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, B., Hoven, C. W., Kaitz, M., Steele, M., Musa, G., Margolis, A., Ewing, J., Sossin, K. M., & Lee, S. H. (2020). Urgent engagement in 9/11 pregnant widows and their infants: Transmission of trauma. Infancy, 25(2), 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Kimhy, R., Erel-Brodsky, H., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2025). ‘COVID-19 belongs to everyone… in this war—We are alone’: Israeli therapists’ perceptions of the pandemic and 2023 war. International Journal of Psychology, 60(2), e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, J. L., Slade, A., Pettit, C., & Shai, D. (2020). I “get” you, babe: Reflective functioning in partners transitioning to parenthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(6), 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brok, E. C., Lok, P., Oosterbaan, D. B., Schene, A. H., Tendolkar, I., & Van Eijndhoven, P. F. (2017). Infant-related intrusive thoughts of harm in the postpartum period: A critical review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(8), e913–e923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brülhart, M., Klotzbücher, V., Lalive, R., & Reich, S. K. (2021). Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature, 600(7887), 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasson, M., Ben-Shlomo, S., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2025). Early parent–child relationship in the shadow of war-related trauma: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M., Ben-Yaakov, O., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2022a). Parenthood in the shadow of COVID-19: The contribution of gender, personal resources and anxiety to first time parents’ perceptions of the infant. Child & Family Social Work, 27(1), 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M., Erel-Brodsky, H., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2024). Mother’s disintegrative responses in the context of infant care: Clinical and empirical evidence of the role of empathy and parity. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 41(2), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2022). The Maternal Disintegrative Responses Scale (MDRS) and its associations with attachment orientation and childhood trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect, 131, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2023). The maternal disintegrative responses scale (MDRS): Development and initial validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(2), 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M., Taubman–Ben-Ari, O., & Abu-Sharkia, S. (2022b). Posttraumatic growth in the wake of COVID-19 among Jewish and Arab pregnant women in Israel. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(8), 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasson, M., Taubman–Ben-Ari, O., & Erel-Brodsky, H. (2023). “I felt like a bad monster was rising up in me”: Empirical and clinical evidence of maternal disintegrative responses in the context of infant care. Feminism & Psychology, 34(1), 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collardeau, F., U, O. L., K, A. Y., Mayhue, J. G., & Fairbrother, N. (2024). Prevalence and course of unwanted, intrusive thoughts of infant-related harm. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 85(3), 23m15145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, S., Bloemhof-Bris, E., Segev, R., Abramovich, M., Levy, G., & Shelef, A. (2024). Anxiety, post-traumatic symptoms, media-induced secondary trauma, post-traumatic growth, and resilience among mental health workers during the Israel–Hamas war. Stress and Health, 40, e3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozio, E., Feldman, M., Bizouerne, C., Drain, E., Laroche Joubert, M., Mansouri, M., Moro, M. R., & Ouss, L. (2020). The transgenerational transmission of trauma: The effects of maternal PTSD in mother–infant interactions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 480690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbrother, N., & Woody, S. R. (2008). New mothers’ thoughts of harm related to the newborn. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 11(3), 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R., & Vengrober, A. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder in infants and young children exposed to war-related trauma. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(7), 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. H., Watson, G. R., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Anxiety disorders in postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 292–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helpman, L., Saragosti, G. Y., Oberman, M., Avrahami, I., & Horesh, D. (2024). Creating new life while lives are lost: Birth in the face of war in Israel after the October 7 attacks. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 42(3), 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, E. A., Garfin, D. R., & Silver, R. C. (2024). It matters what you see: Graphic media images of war and terror may amplify distress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(29), e2318465121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huth-Bocks, A. C., Guyon-Harris, K., Calvert, M., Scott, S., & Ahlfs-Dunn, S. (2016). The caregiving helplessness questionnaire: Evidence for validity and utility with mothers of infants: Disorganized caregiving. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(3), 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igreja, V. (2003). The effects of traumatic experiences on the infant–mother relationship in the former war zones of central Mozambique: The case of madzawde in Gorongosa. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(5), 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaitz, M., Levy, M., Ebstein, R., Faraone, S. V., & Mankuta, D. (2009). The intergenerational effects of trauma from terror: A real possibility. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30(2), 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper-Goldstein, H., Pariente, G., Wainstock, T., Dekel, S., Binyamin, Y., Battat, T. L., Broder, O. W., Kosef, T., & Sheiner, E. (2024). The association of delivery during a war with the risk for postpartum depression, anxiety and impaired maternal-infant bonding, a prospective cohort study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 310, 2863–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, B., Gerson, E. M., Petrillo, S., Langer, A., & Tiemeier, H. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: A scoping review. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahti, K., Vänskä, M., Qouta, S. R., Diab, S. Y., Perko, K., & Punamäki, R. (2019). Maternal experience of their infants’ crying in the context of war trauma: Determinants and consequences. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(2), 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhan, R., Agrawal, A., & Sharma, M. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 11, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, H., Owais, S., Savoy, C. D., & Van Lieshout, R. J. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and mother-infant bonding in women seeking treatment for postpartum depression before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(4), 35146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levavi, K., Yatziv, T., Yakov, P., Pike, A., Deater-Deckard, K., Hadar, A., Bar, G., Froimovici, M., & Atzaba-Poria, N. (2024). Maternal perceptions and responsiveness to cry in armed conflict zones: Links to child behavior problems. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 52, 1455–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y., Groweiss, Y., Blank, C., & Neria, Y. (2024). PTSD, depression, and anxiety after the October 7, 2023 attack in Israel: A nationwide prospective study. eClinicalMedicine, 68, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Wang, S., & Wang, G. (2022). Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(19–20), 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayopoulos, G. A., Ein-Dor, T., Dishy, G. A., Nandru, R., Chan, S. J., Hanley, L. E., Kaimal, A. J., & Dekel, S. (2021a). COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother-infant bonding problems. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayopoulos, G. A., Ein-Dor, T., Li, K. G., Chan, S. J., & Dekel, S. (2021b). COVID-19 positivity associated with traumatic stress response to childbirth and no visitors and infant separation in the hospital. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijalevich-Soker, E., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2025a). Parents’ experience during wartime: Vulnerability, complexity, and parental functioning. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijalevich-Soker, E., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2025b). The contribution of self-compassion and social support to women’s mental health during pregnancy: A comparison between international and national crisis periods. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghassemi, S., Adib Moghaddam, E., & Arab, S. (2024). Safe motherhood in crisis; threats, opportunities, and needs: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 24(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C. A., III, Hazlett, G., Wang, S., Richardson, E. G., Jr., Schnurr, P., & Southwick, S. M. (2001). Symptoms of dissociation in humans experiencing acute, uncontrollable stress: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(8), 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necho, M., Tsehay, M., Birkie, M., Biset, G., & Tadesse, E. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(7), 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osofsky, J. D. (1995). The effects of exposure to violence on young children. American Psychologist, 50(9), 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palgi, Y., Greenblatt-Kimron, L., Hoffman, Y., Segel-Karpas, D., Ben-David, B., Shenkman, G., & Shrira, A. (2024). PTSD symptoms and subjective traumatic outlook in the Israel–Hamas war: Capturing a broader picture of posttraumatic reactions. Psychiatry Research, 339, 116096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preis, H., Mahaffey, B., Heiselman, C., & Lobel, M. (2022). The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on birth satisfaction in a prospective cohort of 2341 US women. Women and Birth, 35(5), 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qouta, S. R., Vänskä, M., Diab, S. Y., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2021). War trauma and infant motor, cognitive, and socioemotional development: Maternal mental health and dyadic interaction as explanatory processes. Infant Behavior and Development, 63, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N., Hetherington, E., McArthur, B. A., McDonald, S., Edwards, S., Tough, S., & Madigan, S. (2021). Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: A longitudinal analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(5), 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, L., Mijalevich-Soker, E., Joffe, E., Awad-Yasin, M., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2024). Post-traumatic stress symptoms and war-related concerns among pregnant women: The contribution of self-mastery and intolerance of uncertainty. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 1–14, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E., Levitt, C., Wong, S., Kaczorowski, J., & McMaster University Postpartum Research Group. (2006). Systematic review of the literature on postpartum care: Effectiveness of postpartum support to improve maternal parenting, mental health, quality of life, and physical health. Birth, 33(3), 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrira, A., & Palgi, Y. (2024). Age differences in acute stress and PTSD symptoms during the 2023 Israel–Hamas war: Preliminary findings. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 173, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuman, C. J., Peahl, A. F., Pareddy, N., Morgan, M. E., Chiangong, J., Veliz, P. T., & Dalton, V. K. (2022). Postpartum depression and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Research Notes, 15(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J., & George, C. (2011). Disorganization of maternal caregiving across two generations. In J. Solomon, & C. George (Eds.), Disorganized attachment and caregiving (pp. 25–51). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tambelli, R., Tosto, S., & Favieri, F. (2025). Psychiatric risk factors for postpartum depression: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubman–Ben-Ari, O., Chasson, M., Abu Sharkia, S., & Weiss, E. (2020). Distress and anxiety associated with COVID-19 among Jewish and Arab pregnant women in Israel. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 38(3), 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman–Ben-Ari, O., Erel-Brodsky, H., Chasson, M., Ben-Yaakov, O., Meir, R., & Screier-Tivoni, A. (2025). Psychological distress and concerns of perinatal women during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic-a case study and empirical comparative examination. Current Psychology, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tees, M. T., Harville, E. W., Xiong, X., Buekens, P., Pridjian, G., & Elkind-Hirsch, K. (2010). Hurricane Katrina-related maternal stress, maternal mental health, and early infant temperament. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(4), 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, S., Kinjo, K., & Fukuda, Y. (2021). The relationship between postpartum depression and social support during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 47(10), 3524–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G., Cook, J., Nowland, R., Donnellan, W. J., Topalidou, A., Jackson, L., & Fallon, V. (2022). Resilience and post-traumatic growth in the transition to motherhood during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative exploratory study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 36(4), 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ee, E., Kleber, R. J., Jongmans, M. J., Mooren, T. T. M., & Out, D. (2016). Parental PTSD, adverse parenting and child attachment in a refugee sample. Attachment & Human Development, 18(3), 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L. K., Kornfield, S. L., Himes, M. M., Forkpa, M., Waller, R., Njoroge, W. F. M., Barzilay, R., Chaiyachati, B. H., Burris, H. H., Duncan, A. F., Seidlitz, J., Parish-Morris, J., Elovitz, M. A., & Gur, R. E. (2023). The impact of postpartum social support on postpartum mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 26(4), 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., Wang, C., Zuo, X., Aertgeerts, B., Buntinx, F., Li, T., & Vermandere, M. (2023). Study characteristical and regional influences on postpartum depression before vs. during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J., Havens, K. L., Starnes, C. P., Pickering, T. A., Brito, N. H., Hendrix, C. L., Thomason, M. E., Vatalaro, T. C., & Smith, B. A. (2021). Changes in social support of pregnant and postnatal mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Midwifery, 103, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic/ Variable | Whole Sample (N = 1416) | Low-Intensity Pandemic (N = 360) | High-Intensity Pandemic (N = 637) | War (N = 419) | Difference Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD; Range)/% (N) | |||||

| Age | M = 31.79 (4.76; 19–47) | M = 30.62 (4.28; 19–45) | M = 31.43 (4.81; 20–46) | M = 33.36 (4.67; 21–47) | F(2, 1413) = 37.17 *** |

| Education | χ2(6, 1415) = 186.78, *** | ||||

| Elementary | 0.8% (11) | 2.2% (8) | 0.3% (2) | 0.2% (1) | |

| High school | 15.0% (212) | 35.9% (129) | 8.2% (52) | 7.4% (31) | |

| Associate degree | 8.1% (115) | 7.0% (25) | 9.7% (62) | 6.7% (28) | |

| Academic degree | 76.1% (1077) | 54.9% (197) | 81.8% (521) | 85.7% (359) | |

| Missing | 0.1% (1) | 0.3% (1) | |||

| Economic status | χ2(6, 1404) = 150.77, *** | ||||

| Below average | 10.3% (144) | 4.6% (16) | 13.6% (87) | 9.8% (41) | |

| Average | 52.1% (731) | 32.2% (112) | 62.3% (397) | 53.0% (222) | |

| Above average | 37.4% (529) | 63.2% (220) | 24.0% (153) | 37.2% (156) | |

| Missing | 0.8% (12) | 3.3% (12) | |||

| Parity | F(2, 1416) = 5.54 ** | ||||

| Primiparous | 39.7% (562) | 44.7% (161) | 35.0% (223) | 42.5% (178) | |

| Multiparous | 60.3% (854) | 55.3% (199) | 65.0% (414) | 57.5% (241) | |

| Intrusive thoughts | M = 0.90 (0.78; 0–4) | M = 0.80 (0.76; 0–4) | M = 0.89 (0.76; 0–4) | M = 1.00 (0.82; 0–4) | F(2, 1403) = 7.38 *** |

| Dissociative experiences | M = 0.39 (0.54; 0–4) | M = 0.30 (0.49; 0–4) | M = 0.38 (0.52; 0–4) | M = 0.48 (0.60; 0–4) | F(2, 1403) = 12.07 *** |

| High-Intensity Pandemic | War | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to the COVID-19 Pandemic | No | Yes | Exposure to 7 October and the Israel–Hamas War | No | Yes | Difference Test |

| Have you contracted the coronavirus? | 98.9% (n = 630) | 1.1% (n = 7) | Did you personally witness the massacre on 7 October or the war that followed? | 96.7% (n = 405) | 3.3% (n = 14) | |

| Do you know someone who has contracted the coronavirus? | 34.1% (n = 217) | 65.9% (n = 420) | Were people close to you (family members or friends) murdered or killed in the massacre on 7 October or in the war that followed? | 83.7% (n = 349) | 16.3% (n = 68) | |

| Have you or anyone in your household been in quarantine due to the coronavirus? | 42.2% (n = 269) | 57.8% (n = 368) | Do you know someone or people who were injured, murdered, or killed in the events of 7 October or in the war that followed? | 48.1% (n = 201) | 51.9% (n = 217) | |

| Overall exposure M (SD) | M = 0.77 (0.77) | M = 0.71 (0.75) | t(1054) = 1.25 p > 0.05 | |||

| Damaged experience of childbirth and childcare resulting from COVID-19 | M (SD) | Range | Damaged experience of childbirth and childcare resulting from 7 October or the war that followed | M (SD) | Range | |

| To what extent do you feel that your childbirth experience was negatively affected by the COVID-19 outbreak and its consequences? | M = 3.76 (1.70) | 1–5 | To what extent do you feel that your childbirth experience was negatively affected by the war? | M = 2.80 (1.26) | 1–5 | t(1024.68) = 10.41 p < 0.001 |

| To what extent do you feel that your caregiving experience with your baby was negatively affected by the COVID-19 outbreak and its consequences? | M = 2.87 (1.52) | 1–5 | To what extent do you feel that your caregiving experience with your baby was negatively affected by the war? | M = 2.75 (1.16) | 1–5 | t(1048) = 1.68 p > 0.05 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | |||||||||

| LI Pandemic | - | 0.225 *** | 0.058 | 0.363 *** | - | - | - | 0.013 | −0.033 |

| HI Pandemic | - | 0.036 | 0.295 *** | 0.373 *** | −0.165 *** | 0.064 | 0.097 | −0.128 *** | −0.133 *** |

| War | - | 0.138 ** | 0.165 *** | 0.264 *** | −0.118 | 0.068 | 0.000 | −0.129 ** | −0.117 |

| 2. Education | |||||||||

| LI Pandemic | - | - | 0.268 ** | 0.143 ** | - | - | - | −0.060 | −0.090 |

| HI Pandemic | - | - | 0.132 *** | 0.068 | 0.100 | −0.059 | −0.077 | 0.081 | −0.063 |

| War | - | - | 0.265 *** | −0.004 | −0.053 | −0.053 | −0.069 | −0.128 ** | −0.034 |

| 3. Economic status | |||||||||

| LI Pandemic | - | - | - | −0.045 | - | - | - | −0.118 | −0.058 |

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | 0.155 *** | −0.049 | 0.013 | 0.030 | −0.120 ** | −0.087 |

| War | - | - | - | 0.071 | −0.107 | −0.075 | −0.061 | −0.094 | −0.081 |

| 4. Parity d | |||||||||

| LI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.189 *** | −0.206 *** |

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | −0.040 | −0.132 *** | −0.004 | −0.177 *** | −0.216 *** |

| War | - | - | - | - | −0.006 | −0.066 | −0.034 | −0.206 *** | −0.160 *** |

| 5. Trauma-related exposure | |||||||||

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | −0.033 | −0.022 | 0.090 | 0.007 |

| War | - | - | - | - | - | 0.100 | 0.129 ** | 0.138 ** | 0.100 |

| 6. Damaged childbirth experience | |||||||||

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.252 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.087 |

| War | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.421 *** | 0.201 *** | 0.206 *** |

| 7. Damaged childcare experience | |||||||||

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.123 ** | 0.055 |

| War | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.251 *** | 0.153 ** |

| 8. Intrusive thoughts | |||||||||

| LI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.406 *** |

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.482 *** |

| War | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.452 *** |

| 9. Dissociative experiences | |||||||||

| LI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| HI Pandemic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| War | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dependent Variable | Constructs | Coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | Indirect Effect | Direct Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrusive thoughts | Age | −0.007 | 0.005 | −1.332 | 0.183 | −0.017 | 0.003 | ||

| Education | 0.044 | 0.039 | 1.115 | 0.265 | −0.033 | 0.122 | |||

| Economic status | −0.074 | 0.036 | −2.022 | 0.043 | −0.145 | −0.002 | |||

| Parity | −0.270 | 0.051 | −5.300 | 0.000 | −0.370 | −0.170 | |||

| Trauma-related exposure (X) | 0.087 | 0.031 | 2.797 | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.087 | 0.08 (0.03) ** | ||

| Damaged childbirth experience (M1) | 0.032 | 0.015 | 2.128 | 0.033 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.001 (002) ns | ||

| Damaged childcare experience (M2) | 0.094 | 0.020 | 4.654 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.094 | 0.007 (0.005) ns | ||

| Dissociative experiences | Age | −0.005 | 0.003 | −1.443 | 0.149 | −0.012 | 0.002 | ||

| Education | −0.022 | 0.028 | −0.789 | 0.429 | −0.078 | 0.033 | |||

| Economic status | −0.029 | 0.026 | −1.115 | 0.264 | −0.080 | 0.022 | |||

| Parity | −0.199 | 0.036 | −5.466 | 0.000 | −0.270 | −0.127 | |||

| Trauma-related exposure (X) | 0.0222 | 0.022 | 0.996 | 0.319 | −0.021 | 0.065 | 0.02 (0.02) ns | ||

| Damaged childbirth experience (M1) | 0.021 | 0.011 | 1.905 | 0.057 | −0.000 | 0.042 | 0.001 (0.001) ns | ||

| Damaged childcare experience (M2) | 0.032 | 0.014 | 2.238 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.061 | 0.002 (0.002) ns |

| Antecedent | Consequence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damaged childbirth experience (M1) | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Trauma-related exposure | −0.034 | 0.079 | −0.430 | 0.667 | −0.190 | 0.122 |

| Group 1 | −1.022 | 0.099 | −10.266 | 0.000 | −1.217 | −0.826 |

| Exposure * group | 0.204 | 0.126 | 1.613 | 0.107 | −0.044 | 0.453 |

| Damaged childcare experience (M2) | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Trauma-related exposure | −0.002 | 0.063 | −0.038 | 0.969 | −0.126 | 0.121 |

| Group | −0.159 | 0.079 | −2.022 | 0.043 | −0.314 | −0.004 |

| Exposure * group | 0.212 | 0.100 | 2.110 | 0.035 | 0.014 | 0.409 |

| Intrusive thoughts (Y) | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Trauma-related exposure | 0.071 | 0.039 | 1.809 | 0.070 | −0.006 | 0.148 |

| Damaged childbirth experience | 0.041 | 0.018 | 2.233 | 0.025 | 0.005 | 0.077 |

| Damaged childcare experience | 0.068 | 0.024 | 2.753 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.117 |

| Group | 0.199 | 0.053 | 3.756 | 0.000 | 0.095 | 0.303 |

| Exposure * roup | 0.027 | 0.063 | 0.441 | 0.658 | −0.095 | 0.151 |

| Damaged childbirth experience * group | 0.030 | 0.037 | 0.823 | 0.410 | −0.042 | 0.103 |

| Damaged childcare experience * group | 0.058 | 0.043 | 1.347 | 0.178 | −0.026 | 0.143 |

| [Model R = 0.31; R2 = 0.10; MSE = 0.572, F [1056] = 10.582; p < 0.001] | ||||||

| Conditional direct effect at different levels of the moderator group: trauma exposure → intrusive thoughts | ||||||

| Group | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| High-intensity pandemic | 0.071 | 0.039 | 1.809 | 0.070 | −0.006 | 0.148 |

| War | 0.099 | 0.049 | 2.002 | 0.045 | 0.002 | 0.196 |

| Conditional indirect effect at different levels of the moderator group: trauma exposure → childbirth damage → intrusive thoughts | ||||||

| Group | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| High-intensity pandemic | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.009 | 0.006 | ||

| War | 0.012 | 0.009 | −0.001 | 0.033 | ||

| Conditional indirect effect at different levels of the moderator group: trauma exposure → childcare damage → intrusive thoughts | ||||||

| Group | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| High-intensity pandemic | −0.000 | 0.004 | −0.009 | 0.009 | ||

| War | 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.057 | ||

| Antecedent | Consequence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damaged childbirth experience (M1) | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Trauma-related exposure | −0.034 | 0.079 | −0.430 | 0.667 | −0.190 | 0.122 |

| Group 1 | −1.022 | 0.099 | −10.266 | 0.000 | −1.217 | −0.826 |

| Exposure * group | 0.204 | 0.126 | 1.613 | 0.107 | −0.044 | 0.453 |

| Damaged childcare experience (M2) | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Trauma-related exposure | −0.002 | 0.063 | −0.038 | 0.969 | −0.126 | 0.121 |

| Group | −0.159 | 0.079 | −2.022 | 0.043 | −0.314 | −0.004 |

| Exposure * group | 0.212 | 0.100 | 2.110 | 0.035 | 0.014 | 0.409 |

| Dissociative experiences (Y) | ||||||

| Coefficient | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Trauma-related exposure | −0.001 | 0.028 | −0.067 | 0.946 | −0.057 | 0.053 |

| Damaged childbirth experience | 0.017 | 0.013 | 1.318 | 0.187 | −0.008 | 0.043 |

| Damaged childcare experience | 0.021 | 0.017 | 1.183 | 0.236 | −0.013 | 0.055 |

| Group | 0.164 | 0.037 | 4.352 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.238 |

| Exposure * group | 0.051 | 0.044 | 1.144 | 0.252 | −0.036 | 0.139 |

| Damaged childbirth experience * group | 0.065 | 0.026 | 2.462 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.117 |

| Damaged childcare experience * group | 0.010 | 0.030 | 0.344 | 0.730 | −0.049 | 0.071 |

| [Model R = 0.28; R2 = 0.07; MSE = 0.280, F [1056] = 8.24; p < 0.001] | ||||||

| Conditional direct effect by group: trauma exposure → dissociative experiences | ||||||

| Group | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| High-intensity pandemic | −0.001 | 0.028 | −0.067 | 0.946 | −0.057 | 0.053 |

| War | 0.049 | 0.035 | 1.402 | 0.161 | −0.019 | 0.118 |

| Conditional indirect effect at different levels of the moderator group: trauma exposure → childbirth damage → dissociative experiences | ||||||

| Group | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| High-intensity pandemic | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.002 | ||

| War | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.034 | ||

| Conditional indirect effect at different levels of the moderator group: trauma exposure → childcare damage → dissociative experiences | ||||||

| Group | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| High-intensity pandemic | −0.000 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.003 | ||

| War | 0.006 | 0.006 | −0.004 | 0.022 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chasson, M.; Borelli, J.L.; Shai, D.; Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. Maternal Intrusive Thoughts and Dissociative Experiences in the Context of Early Caregiving Under Varying Levels of Societal Stress. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060717

Chasson M, Borelli JL, Shai D, Taubman – Ben-Ari O. Maternal Intrusive Thoughts and Dissociative Experiences in the Context of Early Caregiving Under Varying Levels of Societal Stress. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060717

Chicago/Turabian StyleChasson, Miriam, Jessica L. Borelli, Dana Shai, and Orit Taubman – Ben-Ari. 2025. "Maternal Intrusive Thoughts and Dissociative Experiences in the Context of Early Caregiving Under Varying Levels of Societal Stress" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060717

APA StyleChasson, M., Borelli, J. L., Shai, D., & Taubman – Ben-Ari, O. (2025). Maternal Intrusive Thoughts and Dissociative Experiences in the Context of Early Caregiving Under Varying Levels of Societal Stress. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060717