Gender-Specific Transmission of Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Families: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis Based on the China Family Panel Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Network Analysis to Explore the Transmission of Depressive Symptoms

1.2. Potential Gender Patterns in the Transmission of Depressive Symptoms

1.3. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedures

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.2. Demographic Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

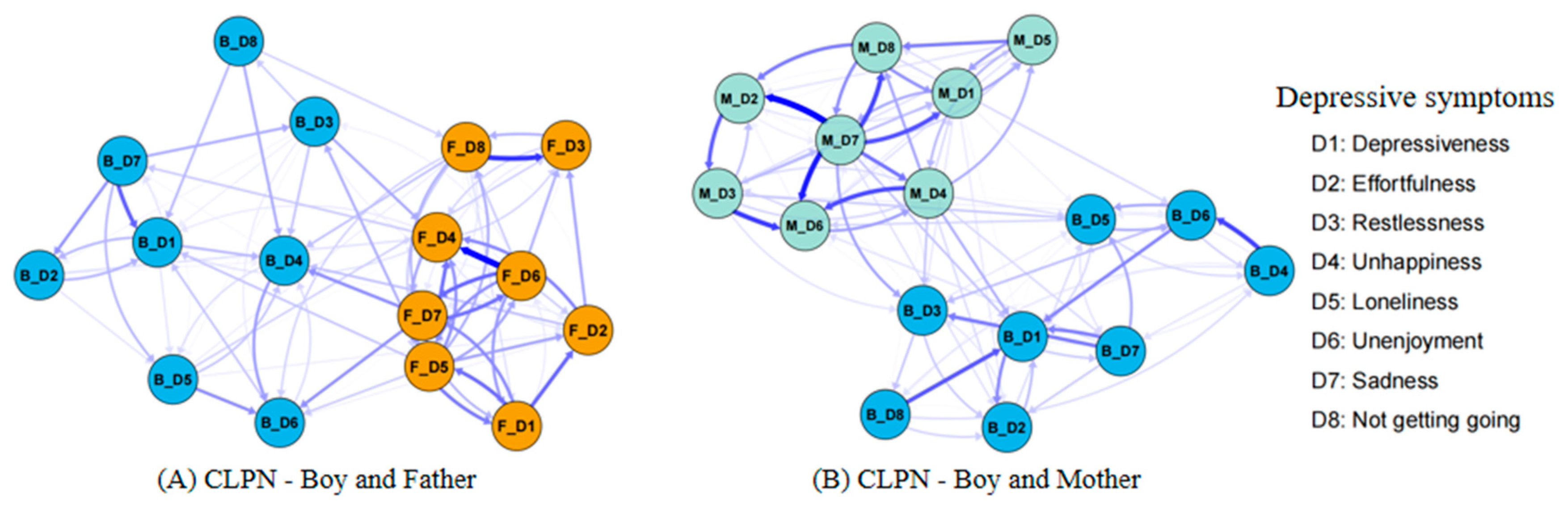

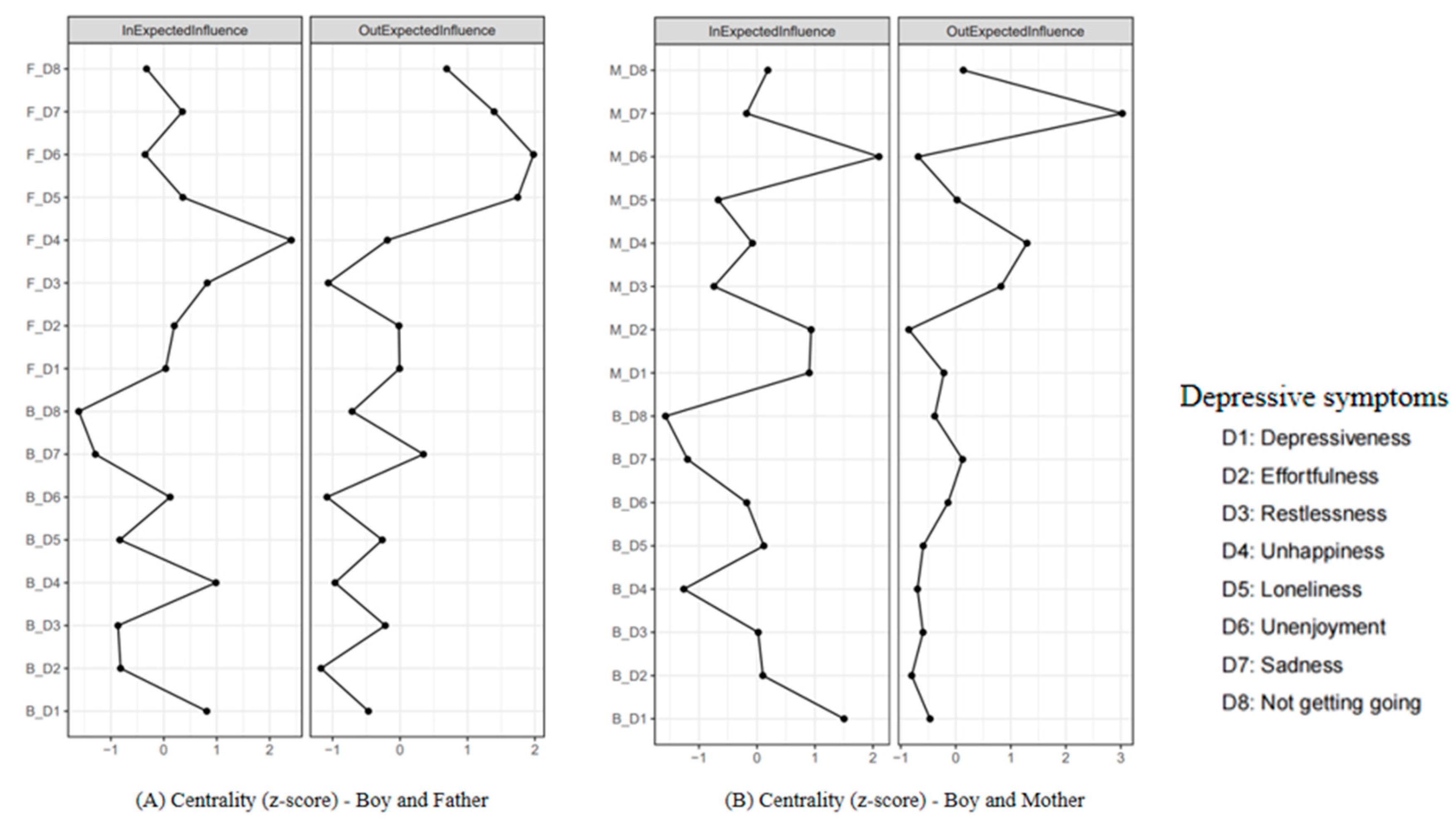

3.1. Comparing the Boy–Father CLPN and the Boy–Mother CLPN

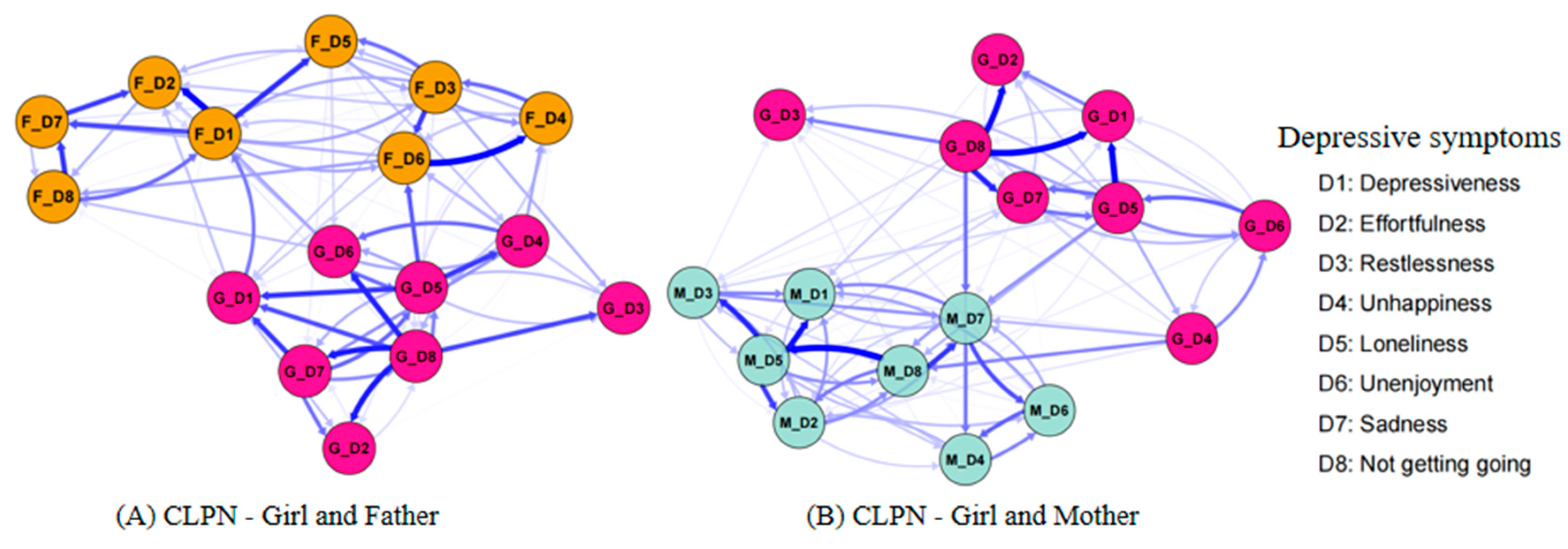

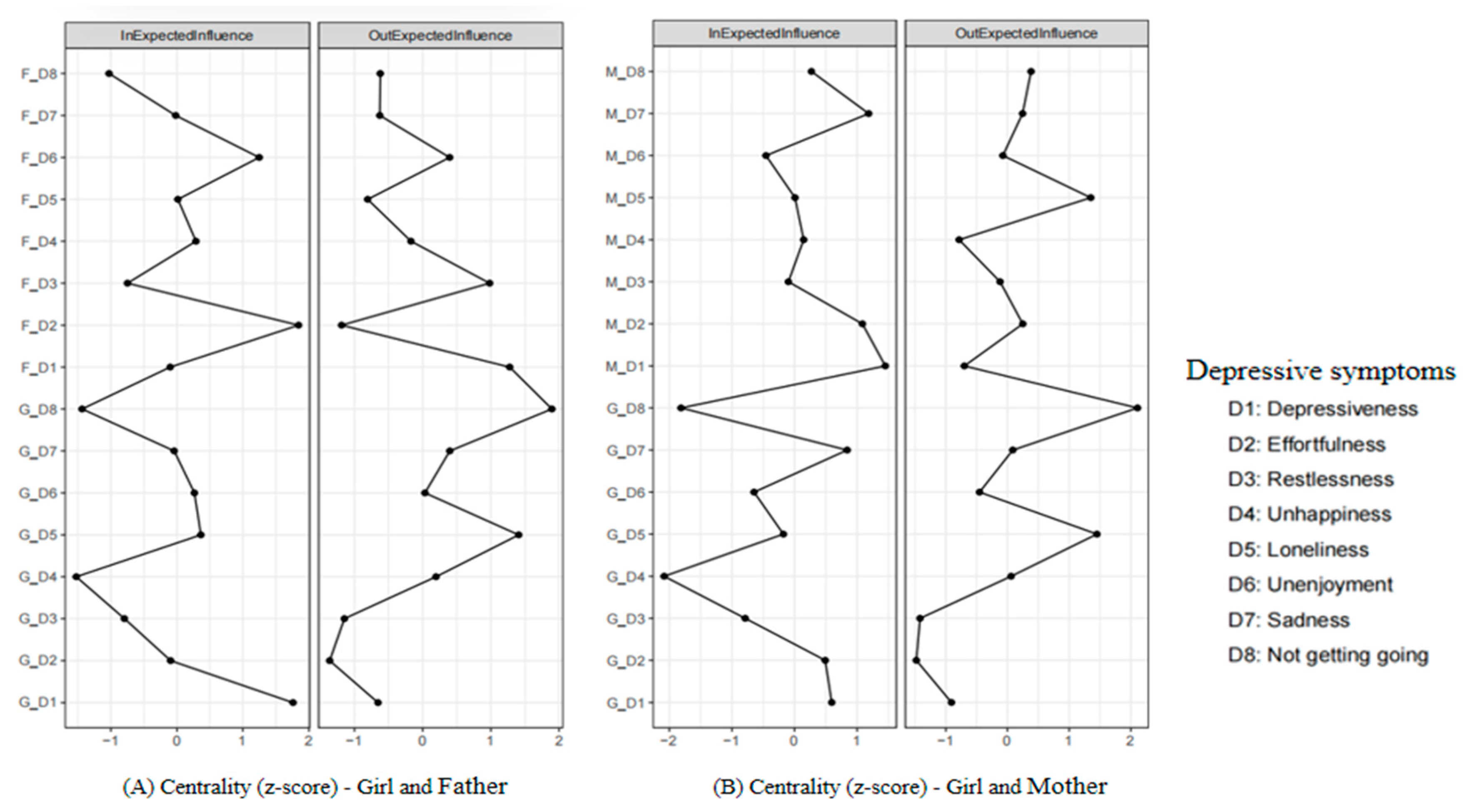

3.2. Comparing the Girl–Father CLPN and the Girl–Mother CLPN

3.3. Comparing the Boy–Father CLPN and the Girl–Father CLPN

3.4. Comparing the Boy–Mother CLPN and the Girl–Mother CLPN

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparing the Parental Influences on Boys and Girls

4.2. Comparing the Influences of Boys and Girls on Parents

4.3. Irregular IEI and Unstable BEI

4.4. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLPN | cross-lagged panel network |

| CFPS | China Family Panel Studies |

| IEI | in-expected influence |

| OEI | out-expected influence |

| BEI | bridge expected influence |

| CIs | confidence intervals |

References

- Branje, S., Geeraerts, S., de Zeeuw, E. L., Oerlemans, A. M., Koopman-Verhoeff, M. E., Schulz, S., Nelemans, S., Meeus, W., Hartman, C. A., Hillegers, M. H. J., Oldehinkel, A. J., & Boomsma, D. I. (2020). Intergenerational transmission: Theoretical and methodological issues and an introduction to four Dutch cohorts. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 45, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brix, N., Ernst, A., Lauridsen, L. L. B., Parner, E., Støvring, H., Olsen, J., Henriksen, T. B., & Ramlau-Hansen, C. H. (2019). Timing of puberty in boys and girls: A population-based study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 33(1), 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, R. D., Silk, J. S., Lee, K. H., Siegle, G. S., Dahl, R. E., Forbes, E. E., Ryan, N. D., Hooley, J. M., & Ladouceur, C. D. (2021). Parents still matter! Parental warmth predicts adolescent brain function and anxiety and depressive symptoms 2 years later. Development and Psychopathology, 33(1), 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection (p. xiv, 317). W W Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Cattarinussi, G., Aarabi, M. H., Sanjari Moghaddam, H., Homayoun, M., Ashrafi, M., Soltanian-Zadeh, H., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Effect of parental depressive symptoms on offspring’s brain structure and function: A systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 131, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T. M. (2015). Gender and emotion expression: A developmental contextual perspective. Emotion Review: Journal of the International Society for Research on Emotion, 7(1), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Liao, J., Ran, F., Wang, X., Liu, Y., & Zhang, W. (2025). Longitudinal associations between future time perspective, sleep problems, and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students: Between-and within-person effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 54(2), 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choukas-Bradley, S., Roberts, S. R., Maheux, A. J., & Nesi, J. (2022). The perfect storm: A developmental-sociocultural framework for the role of social media in adolescent girls’ body image concerns and mental health. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 25(4), 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, D. M., Cremone, A., Kurdziel, L. B. F., Desrochers, P., LeBourgeois, M. K., Sayer, A., Ertel, K., & Spencer, R. M. C. (2016). Maternal depressive symptoms and household income in relation to sleep in early childhood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41(9), 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laat, S. A. A., Huizink, A. C., Hof, M. H., & Vrijkotte, T. G. M. (2018). Socioeconomic inequalities in psychosocial problems of children: Mediating role of maternal depressive symptoms. European Journal of Public Health, 28(6), 1062–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demkowicz, O., Jefferson, R., Nanda, P., Foulkes, L., Lam, J., Pryjmachuk, S., Evans, R., Dubicka, B., Neill, L., Winter, L. A., & Nnamani, G. (2025). Adolescent girls’ explanations of high rates of low mood and anxiety in their population: A co-produced qualitative study. BMC Women’s Health, 25(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmitrieva, J., & Espel, E. V. (2023). The role of paternal and maternal warmth and hostility on daughter’s psychosocial outcomes: The insidious effects of father warmth combined with high paternal hostility. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 930371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q. B., McKone, K. M. P., Hamilton, J. L., Stone, L. B., Ladouceur, C. D., & Silk, J. S. (2025). The link between adolescent girls’ interpersonal emotion regulation with parents and peers and depressive symptoms: A real-time investigation. Development and Psychopathology, 37(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, M., & Kelly, R. J. (2017). Family functioning and children’s sleep. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, M., Kelly, R. J., Bagley, E. J., & Wetter, E. K. (2012). Parental depressive symptoms and children’s sleep: The role of family conflict. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 53(7), 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Rhemtulla, M., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Generalized network psychometrics: Combining network and latent variable models. Psychometrika, 82(4), 904–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P., Wang, T., Wang, J., & Wang, J. (2024). Network analysis of comorbid depression and anxiety and their associations with response style among adolescents with subthreshold depression. Current Psychology, 43(10), 8665–8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E. I., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2017). Moving forward: Challenges and directions for psychopathological network theory and methodology. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 12(6), 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. H., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2010). Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garabiles, M. R., Lao, C. K., Xiong, Y., & Hall, B. J. (2019). Exploring comorbidity between anxiety and depression among migrant Filipino domestic workers: A network approach. Journal of Affective Disorders, 250, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W., Rolls, E. T., Du, J., Feng, J., & Cheng, W. (2021). Brain structure is linked to the association between family environment and behavioral problems in children in the ABCD study. Nature Communications, 12(1), 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X., Bi, T., Zhang, L., & Zhou, J. (2024). Maternal depressive symptoms and offspring internalizing problems: A cross-lagged panel network analysis in late childhood and early adolescence. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 52(10), 1607–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, P. Z., Murray, A. L., Smith, K., Allegrini, A. G., Piazza, G. G., Larsson, H., Epskamp, S., Whalley, H. C., & Kwong, A. S. F. (2025). Network temperature as a metric of stability in depression symptoms across adolescence. Nature Mental Health, 3, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Gao, Q., Wu, R., Ying, J., & You, J. (2022). Parental psychological control, parent-related loneliness, depressive symptoms, and regulatory emotional self-efficacy: A moderated serial mediation model of nonsuicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 26(3), 1462–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 23(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, C., & Sanborn, K. (2002). Puberty and the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 30(4), 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A., Jones, P. J., & McNally, R. J. (2018). Mapping network connectivity among symptoms of social anxiety and comorbid depression in people with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 228, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-S., Gao, C., Xiao, W.-Q., Zhang, X.-Y., Zhong, X.-W., Qin, Y.-Q., Lu, M.-S., Zhang, C.-H., Yang, K., Liang, J.-M., Wang, C. C., Ma, R. C. W., He, J.-R., & Qiu, X. (2025). Association of childhood obesity with pubertal development in boys: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 26(3), e13869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92(4), 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Li, R., Wu, H., Li, C., Wu, Y., & Tao, Q. (2019). The reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) for Chinese University students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakihara, F., Tilton-Weaver, L., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2010). The relationship of parental control to youth adjustment: Do youths’ feelings about their parents play a role? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1442–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M. Y., & He, G. (2018). Resource bargaining and gender display in housework and care work in modern China. Chinese Sociological Review, 50(2), 188–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimes-Dougan, B., & Bolger, A. K. (1998). Coping with maternal depressed affect and depression: Adolescent children of depressed and well mothers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, M., Luoma, I., Salmelin, R., & Tamminen, T. (2014). Maternal depressive symptoms: Associations with adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems and social competence. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 68(5), 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, J. A., Ramos, J. V., Ghimire, L., Rai, S., Kohrt, B. A., & Burkey, M. D. (2019). Gender and child behavior problems in rural nepal: Differential expectations and responses. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaper, C., & Friedman, C. K. (2007). The socialization of gender. In Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 561–587). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G., Neary, M., Polek, E., Flouri, E., & Lewis, G. (2017). The association between paternal and adolescent depressive symptoms: Evidence from two population-based cohorts. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 4(12), 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. Y., Chen, J., Peng, M., Zhou, J., Chen, X., Tan, X., Wang, N., Ma, H., Guo, L., Zhang, J., Wing, Y.-K., Geng, Q., & Ai, S. (2023). Association between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome: Linear and nonlinear Mendelian randomization analyses. Journal of Translational Medicine, 21(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., & Yu, J. (2024). Fathering, living arrangements, and child development in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 56(2), 176–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2021). The gender difference in family educational investment. Youth Research, 5, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Livings, M. S. (2021). The gendered relationship between maternal depression and adolescent internalizing symptoms. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 291, 114464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A., Broadbent, A., Brooks, E., Bulsara, K., Donoghue, K., Saijaf, R., Sampson, K. N., Thomson, A., Fearon, P., & Lawrence, P. J. (2023). The impact of family interventions on communication in the context of anxiety and depression in those aged 14–24 years: Systematic review of randomised control trials. BJPsych Open, 9(5), e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., Chen, F., Ke, L., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., & Luo, Y. (2023). Interparental conflict and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. Development and Psychopathology, 35(2), 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Song, L. (2013). Chinese parents’ goals and practices in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. F., Maughan, B., Konac, D., & Barker, E. D. (2023). Mother and father depression symptoms and child emotional difficulties: A network model. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 222(5), 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middeldorp, C. M., Wesseldijk, L. W., Hudziak, J. J., Verhulst, F. C., Lindauer, R. J. L., & Dieleman, G. C. (2016). Parents of children with psychopathology: Psychiatric problems and the association with their child’s problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(8), 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, T., Franceschini, C., & Musetti, A. (2023). Loneliness and problematic social networking sites use in young adults with poor vs. good sleep quality: The moderating role of gender. Addictive Behaviors, 142, 107687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NeuroLaunch Editorial Team. (2024). Emotional girls: Navigating feelings and empowerment in today’s world. NeuroLaunch Editorial Team. Available online: https://neurolaunch.com/emotional-girl (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Pardini, D. A. (2008). Novel insights into longstanding theories of bidirectional parent–child influences: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J. R., & Yoon, K. L. (2023). Interpersonal factors, peer relationship stressors, and gender differences in adolescent depression. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(11), 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Rhemtulla, M., Bork, R. V., & Cramer, A. (2017). Cross-lagged network models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Cross-Lagged-Network-Models-Rhemtulla-Bork/fbb8ab2cea6c60c65b3254aeb2f0325009ac0f59 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S., Nelemans, S. A., Oldehinkel, A. J., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2021). Examining intergenerational transmission of psychopathology: Associations between parental and adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms across adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 57(2), 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifaki, M., Midouhas, E., Papachristou, E., & Flouri, E. (2021). Reciprocal relationships between paternal psychological distress and child internalising and externalising difficulties from 3 to 14 years: A cross-lagged analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(11), 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, J. A., Levenson, R. W., & Ebling, R. (2005). Cultures of moderation and expression: Emotional experience, behavior, and physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion, 5(2), 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekhoven, D. J., & Bühlmann, P. (2012). MissForest—Non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics, 28(1), 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H., Zhu, L., Zhang, X., & Qiu, B. (2023). The relationship between cognitive resource consumption during gameplay and postgame aggressive behaviors: Between-subjects experiment. JMIR Serious Games, 11, e48317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H., Zhu, L., Zhang, X., & Qiu, B. (2024). When games influence words: Gaming addiction among college students increases verbal aggression through risk-biased drifting in decision-making. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vist Hagen, R., Haga, M., Sigmundsson, H., & Lorås, H. (2022). The association between academic achievement in physical education and timing of biological maturity in adolescents. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0265718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R., Zhang, X., Zhu, L., Teng, H., Zhang, D., & Qiu, B. (2025). The double-edged sword effect of empathic concern on mental health and behavioral outcomes: The mediating role of excessive adaptation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner-Seidler, A., Hitchcock, C., Hammond, E., Hill, E., Golden, A.-M., Breakwell, L., Ramana, R., Moore, R., & Dalgleish, T. (2020). Emotional complexity across the life story: Elevated negative emodiversity and diminished positive emodiversity in sufferers of recurrent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Xie, Y., & Hu, J. (2014). An introduction to the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Chinese Sociological Review, 47, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N., Liu, Y., Ansari, A., Li, K., & Li, X. (2021). Mothers’ depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Examining reciprocal trait-state effects from age 2 to 15. Child Development, 92(6), 2496–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., He, T., Wu, Q., Chi, P., & Lin, X. (2024). Transmission of depressive symptoms in the nuclear family: A cross-sectional and cross-lagged network perspective. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(9), 3145–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Teng, H., Zhu, L., & Qiu, B. (2025). Short-term exposure to aggressive card game: Releasing emotion without escalating post-game aggression. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1505360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Webb, H. J., Farrell, L. J., & Waters, A. M. (2018). Girls’ and boys’ trajectories of appearance anxiety from age 10 to 15 years are associated with earlier maturation and appearance-related teasing. Development and Psychopathology, 30(1), 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Adolescent Boys | Adolescent Girls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | |||||

| Age, years, T1 | 13.76 (2.58) | 760 | 13.85 (2.56) | 709 | ||||

| Age, years, T2 | 15.64 (2.54) | 760 | 15.59 (2.57) | 709 | ||||

| Annual Family income, RMB, T1 | 104,819 (128,462) | 706 | 103,403 (119,999) | 700 | ||||

| Annual Family income, RMB, T2 | 116,172 (129,738) | 699 | 119,648 (203,038) | 639 | ||||

| Ethnicity | n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Han | 665 (87.50%) | 614 (86.60%) | ||||||

| non-Han | 95 (12.50%) | 95 (13.40%) | ||||||

| Maternal level | Paternal level | Maternal level | Paternal level | |||||

| M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | |

| Age, years, T1 | 38.12 (5.34) | 760 | 41.36 (5.58) | 688 | 37.87 (5.15) | 709 | 40.87 (5.42) | 612 |

| Age, years, T2 | 39.98 (5.38) | 760 | 43.11 (5.57) | 688 | 39.74 (5.12) | 760 | 42.76 (5.39) | 612 |

| Educational level | n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Primary school and below | 323 (42.50%) | 297 (43.17%) | 276 (38.93%) | 262 (38.08%) | ||||

| Secondary school | 207 (27.23%) | 188 (27.33%) | 200 (28.21%) | 175 (25.44%) | ||||

| Post-secondary | 100 (13.16%) | 103 (14.97%) | 113 (15.94%) | 96 (13.95%) | ||||

| Bachelor and above | 70 (9.21%) | 51 (7.41%) | 44 (6.21%) | 24 (3.49%) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | Boy–Parent Cross-Lagged Panel Network | Girl–Parent Cross-Lagged Panel Network | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy’s Levels M (SD) | Maternal Levels M (SD) | Paternal Levels M (SD) | Girl’s Levels M (SD) | Maternal Levels M (SD) | Paternal Levels M (SD) | |||||||

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |

| D1 | 1.63 (0.75) | 1.52 (0.70) | 1.82 (0.76) | 1.87 (0.75) | 1.72 (0.76) | 1.77 (0.78) | 1.68 (0.76) | 1.65 (0.75) | 1.85 (0.82) | 1.92 (0.82) | 1.71 (0.77) | 1.76 (0.79) |

| D2 | 1.54 (0.72) | 1.45 (0.65) | 1.71 (0.76) | 1.75 (0.77) | 1.68 (0.80) | 1.71 (0.79) | 1.56 (0.77) | 1.60 (0.71) | 1.73 (0.81) | 1.78 (0.81) | 1.69 (0.80) | 1.78 (0.85) |

| D3 | 1.48 (0.76) | 1.52 (0.80) | 1.75 (0.87) | 1.87 (0.92) | 1.72 (0.89) | 1.77 (0.88) | 1.47 (0.78) | 1.58 (0.80) | 1.83 (0.92) | 1.92 (0.92) | 1.72 (0.86) | 1.76 (0.90) |

| D4 | 1.85 (0.83) | 1.87 (0.80) | 2.10 (0.92) | 2.04 (0.88) | 2.09 (0.93) | 2.07 (0.91) | 1.78 (0.83) | 1.79 (0.79) | 2.08 (0.94) | 2.09 (0.92) | 2.01 (0.92) | 2.06 (0.90) |

| D5 | 1.40 (0.70) | 1.36 (0.63) | 1.45 (0.65) | 1.53 (0.71) | 1.48 (0.72) | 1.50 (0.72) | 1.39 (0.67) | 1.42 (0.66) | 1.48 (0.72) | 1.59 (0.79) | 1.48 (0.74) | 1.60 (0.81) |

| D6 | 1.73 (0.75) | 1.75 (0.74) | 2.00 (0.87) | 1.88 (0.87) | 1.97 (0.91) | 1.93 (0.89) | 1.65 (0.76) | 1.69 (0.74) | 1.98 (0.88) | 1.98 (0.90) | 1.92 (0.91) | 1.96 (0.87) |

| D7 | 1.50 (0.69) | 1.44 (0.65) | 1.60 (0.64) | 1.66 (0.68) | 1.49 (0.67) | 1.52 (0.63) | 1.52 (0.68) | 1.56 (0.69) | 1.62 (0.69) | 1.70 (0.77) | 1.50 (0.66) | 1.56 (0.74) |

| D8 | 1.12 (0.44) | 1.12 (0.42) | 1.24 (0.55) | 1.29 (0.61) | 1.18 (0.52) | 1.22 (0.54) | 1.15 (0.46) | 1.18 (0.52) | 1.25 (0.56) | 1.32 (0.67) | 1.22 (0.58) | 1.29 (0.65) |

| Boy–Father CLPN | Boy–Mother CLPN | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Edge Weight | Measure | Edge Weight |

| F_D7 → B_D4 | 0.08 | M_D7 → B_D3 | 0.06 |

| F_D7 → B_D6 | 0.08 | M_D4 → B_D1 | 0.06 |

| F_D5 → B_D3 | 0.06 | M_D4 → B_D3 | 0.04 |

| B_D5 → F_D3 | 0.06 | M_D7 → B_D1 | 0.04 |

| B_D3 → F_D4 | 0.06 | M_D3 → B_D5 | 0.04 |

| F_D2 → B_D4 | 0.05 | B_D5 → M_D6 | 0.03 |

| F_D8 → B_D4 | 0.05 | M_D8 → B_D6 | 0.03 |

| F_D5 → B_D1 | 0.05 | M_D4 → B_D7 | 0.03 |

| F_D4 → B_D7 | 0.04 | M_D4 → B_D5 | 0.03 |

| F_D5 → B_D6 | 0.04 | M_D4 → B_D2 | 0.03 |

| B_D8 → F_D8 | 0.04 | M_D7 → B_D2 | 0.03 |

| F_D8 → B_D6 | 0.04 | M_D3 → B_D3 | 0.02 |

| Girl–Father CLPN | Girl–Mother CLPN | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Edge Weight | Measure | Edge Weight |

| G_D5 → F_D6 | 0.10 | G_D8 → M_D7 | 0.09 |

| G_D1 → F_D1 | 0.08 | G_D4 → M_D8 | 0.08 |

| G_D4 → F_D4 | 0.06 | G_D5 → M_D7 | 0.07 |

| G_D6 → F_D1 | 0.05 | G_D4 → M_D7 | 0.05 |

| F_D3 → G_D3 | 0.05 | G_D5 → M_D8 | 0.05 |

| G_D4 → F_D6 | 0.05 | G_D8 → M_D1 | 0.04 |

| G_D6 → F_D8 | 0.04 | G_D8 → M_D4 | 0.03 |

| F_D5 → G_D4 | 0.04 | M_D5 → G_D7 | 0.03 |

| G_D1 → F_D2 | 0.04 | G_D5 → M_D3 | 0.03 |

| G_D6 → F_D2 | 0.04 | G_D7 → M_D1 | 0.03 |

| G_D5 → F_D4 | 0.04 | G_D8 → M_D3 | 0.03 |

| G_D3 → F_D6 | 0.03 | G_D4 → M_D2 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Fang, N.; Wang, R.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, D.; Teng, H.; Qiu, B. Gender-Specific Transmission of Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Families: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis Based on the China Family Panel Studies. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050672

Zhang X, Fang N, Wang R, Zhu L, Zhang D, Teng H, Qiu B. Gender-Specific Transmission of Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Families: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis Based on the China Family Panel Studies. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050672

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xuanyu, Nan Fang, Rui Wang, Lixin Zhu, Dengdeng Zhang, Huina Teng, and Boyu Qiu. 2025. "Gender-Specific Transmission of Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Families: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis Based on the China Family Panel Studies" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050672

APA StyleZhang, X., Fang, N., Wang, R., Zhu, L., Zhang, D., Teng, H., & Qiu, B. (2025). Gender-Specific Transmission of Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Families: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis Based on the China Family Panel Studies. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050672