1. Introduction

The responsibilities of salespeople have fundamentally transformed due to their pivotal role in executing corporate strategies. The traditional model, which evaluates performance primarily through revenue and profit, is no longer sufficient (

Elsaied, 2025;

Forkmann et al., 2022;

Kraft et al., 2019). In response to growing uncertainty and intense competition, companies now expect employees to take more proactive initiatives (

Nwanzu & Babalola, 2024). Previous organizational-level research has predominantly focused on motivating employees’ proactive behaviors by emphasizing the organizational climate (

Kang et al., 2016), human resource development (

Sim et al., 2024;

Van Lancker et al., 2022), and leadership styles (

Mäkelä et al., 2024). Nevertheless, the distinct role of front-line managers within organizations has received relatively little attention (

Zhao et al., 2024). Given that front-line employees interact more frequently with these managers and view them as organizational representatives (

Eisenberger et al., 2014), enhancing employee proactivity may require greater involvement from front-line managers.

The business community has taken the lead over academia in supporting front-line managers through management practices. For instance, the Chinese supermarket chain Pang Donglai empowers its front-line supervisors, thereby enabling sales staff to exhibit more proactive behaviors. This initiative has not only significantly boosted revenue and enhanced customer reputation but also established Pang Donglai as one of China’s leading private supermarkets (

Qian, 2024 in Chinese). This case highlights the untapped potential of front-line managers who not only influence employee behavior but also directly enhance organizational performance (

Kou et al., 2022;

Chang et al., 2020). Additionally, research indicates that front-line managers play a critical role in determining the job satisfaction and performance of front-line employees (

Karltun et al., 2023;

Huo et al., 2020), serving as the crucial link between top management and the interests of employees (

Townsend & Kellner, 2015).

Although front-line managers play a crucial role, academic research on motivating them and providing positive feedback to front-line employees remains underdeveloped (

Zhao et al., 2024;

Doldor et al., 2019). This is significant because only by adopting a positive attitude can front-line managers create an environment that fosters proactive behavior among employees. However, front-line managers may be reluctant to assist employees, particularly in a negative organizational climate, which can undermine collaboration, focus, and creativity (

Karltun et al., 2023). Adequate organizational support is vital for front-line managers to form positive expectations, alleviate uncertainty-related pressure (

Tan et al., 2024) and enhance interactions with employees. In summary, it is imperative to consider front-line managers’ perceptions of the organizational environment. They require organizational support not only to ensure positive social exchanges (

Eisenberger et al., 2014) but also to encourage a greater investment of time and effort in front-line operations (

Aldabbas et al., 2023), ultimately enhancing the performance of front-line employees.

This study investigates the reasons for front-line managers’ perceptions of organizational support based on three key considerations. First, unlike prior research focusing on supervisors’ personality traits or leadership styles, this study highlights organizational support as a situational factor that organizations can actively improve and adjust (

Ding et al., 2022) This support directly influences employees’ attitudes and behaviors by providing practical opportunities for front-line managers (

Op De Beeck et al., 2018). Second, career initiative requires emotional commitment and autonomous motivation (

Ayed et al., 2024), both of which are closely linked to perceived organizational support (

Eisenberger et al., 2020). Front-line employees’ perception of organizational support is mediated through supervisors: when supervisors perceive support, they reciprocate by fostering positive leader–member exchanges (LMX) and offering emotional and resource support to subordinates, enabling front-line employees to experience organizational support (

Eisenberger et al., 2014). Therefore, we argue that supervisor’s perceived organizational support (SPOS) serves as a critical driver of career initiatives among front-line personnel. Thirdly, analyzing the antecedents and mechanisms of career initiative among front-line salespeople enhances the logical framework of proactive behavior research.

While some scholars have noted that SPOS can foster employees’ innovative behavior (

Pan et al., 2012) or reduce withdrawal behavior (

Eisenberger et al., 2014), these studies do not explicitly elucidate the underlying motivations driving such employee behaviors. To address this gap, we incorporate self-determination theory (SDT), which posits that external environmental factors can facilitate intrinsic motivation, enabling individuals to autonomously choose their behaviors. According to SDT, both the environment and intrinsic motivation are critical determinants of behavior (

Deci et al., 2017).

We argue that when front-line managers perceive organizational support, they can foster an inclusive environment through their behaviors, promoting mutual respect and harmonious interactions among employees. This, in turn, creates the necessary conditions for stimulating autonomous motivation (

Shore et al, 2011;

Randel et al., 2018). Although LMX theory partially explains this phenomenon, the concept of inclusiveness provides a more comprehensive description of the overall organizational environment. Furthermore, the transformation of supervisors’ perceptions directly influences changes in the team environment (

Carmeli et al., 2010), as an inclusive climate encompasses team-level interactions rather than being limited to dyadic relationships between supervisors and individual employees (

Shore & Chung, 2024).

On the other hand, front-line sales personnel who perceive support from their supervisors and an inclusive team environment develop a strong sense of obligation toward the organization, becoming “responsible citizens” (

Cheng et al., 2022). Felt obligation serves as a key motivational factor driving proactive behaviors (

Eisenberger et al., 2014). Although variables such as psychological safety can also encourage such behaviors, felt obligation uniquely influences front-line sales personnel due to their significant autonomy and limited direct supervision (

Lyngdoh et al., 2023). A robust sense of responsibility is crucial for balancing freedom with mission fulfillment (

Thompson et al., 2020), fostering self-driven proactivity (

Ayed et al., 2024). Therefore, we emphasize inclusive climate and felt obligation as critical mechanisms explaining how perceived organizational support from supervisors translates into proactive behaviors among front-line sales personnel.

Furthermore, it is crucial to recognize that external environmental factors and the personal characteristics of salespeople may jointly influence the generation of proactive behavior motivation (

Zhao et al., 2024). While positive social exchange is a universal human trait, individuals vary in their acceptance of the balance between giving and receiving (

Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). This dimension has received limited attention in studies of autonomous motivation. We thus incorporate core self-evaluation (CSE) as a pivotal factor shaping salespeople’s positive choices. High CSE strengthens self-efficacy and fosters self-determination, whereas low CSE may impede proactivity even with managerial support due to inadequate self-esteem and confidence (

Li & Ding, 2022). Based on this discussion, this study proposes the following research questions (RQ):

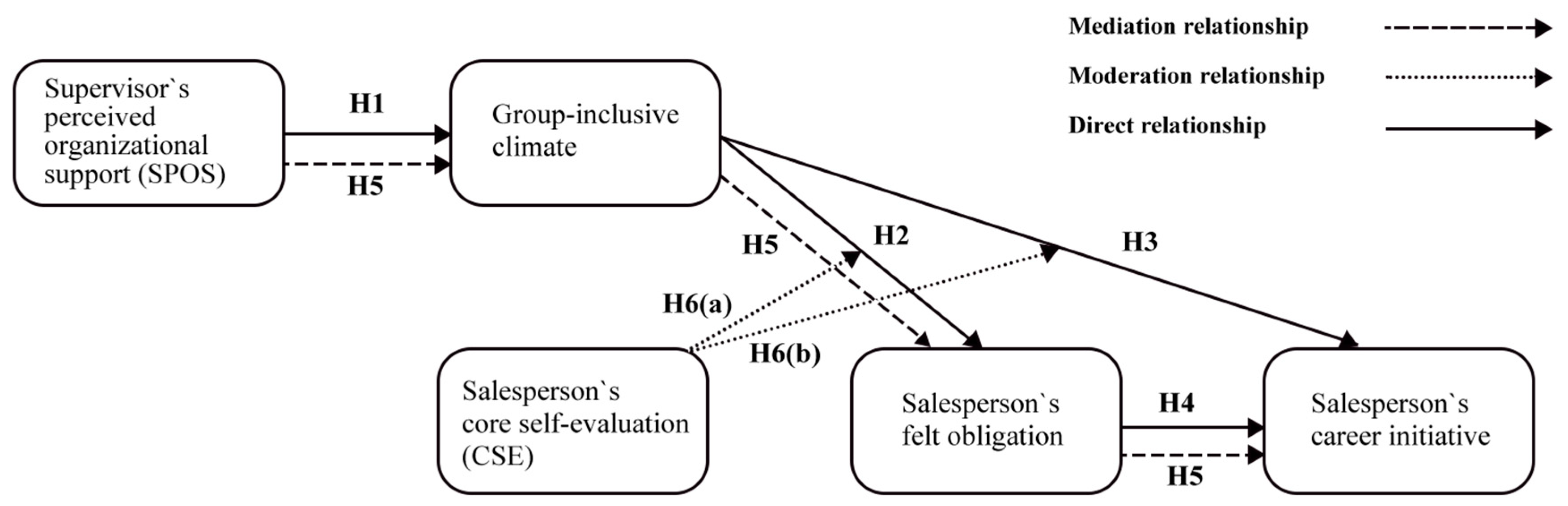

RQ1: How does the organizational support perceived by front-line managers influence the career initiative of front-line salespeople?

RQ2: Do group-inclusive climate and felt obligation mediate the relationship between SPOS and salesperson’s career initiative?

RQ3: Does salesperson’s CSE moderate the relationships between group-inclusive climate and felt obligation, as well as between group-inclusive climate and salesperson’s career initiative?

To address the above questions, we propose a theoretical framework that elucidates how SPOS influences salespeople’s career initiative. This study makes three key contributions: First, we extend the antecedents of career initiative among front-line salespeople and delineate a pathway from supervisors’ perceptions to career initiative, with practical implications for management practice. Second, by integrating self-determination theory and social exchange theory, we clarify how supervisors’ perceptions indirectly foster career initiative through creating an inclusive team climate and salespeople’s felt obligation. Third, we investigate the moderating role of core self-evaluation (CSE) in shaping career initiative, offering insights into why some employees exhibit greater proactivity than others despite comparable levels of organizational support.

The structure of this article is as follows. The first part reviews the literature about SPOS, group-inclusive climate, felt obligation, career initiative, and core self-evaluation, and it formulates the hypotheses for this study. The second part provides a detailed overview of the research methods. In the third part, the analysis and results are thoroughly presented. The fourth part provides a detailed discussion of the study findings, and the final part provides a summary of the conclusions, addresses the limitations, and outlines directions for future research.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach

In this study, we employed a questionnaire survey method. First, this approach facilitates the collection and analysis of data (

Hussain et al., 2023). Second, it enables the acquisition of reliable data from a substantial number of respondents within a constrained timeframe (

Chaudhry et al., 2023). According to Hennessy and Patterson (

Hennessy & Patterson, 2011), designing measurement instruments is a crucial initial step for conducting survey analysis. Consequently, we developed a measurement instrument to ensure effective data collection.

3.2. Instrument

The measurement instrument in this study encompasses five variables: SPOS, group-inclusive climate, felt obligation, career initiative, and CSE. We selected established scales from existing research that have been formally published and validated for effective measurement. To ensure cultural and linguistic accuracy, we conducted the translation and back-translation of the scales. Through a pilot test, we analyzed the reliability and validity of the scales and carried out revisions based on feedback from the respondents. Each scale achieved an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7 or higher. The measurement instrument consists of 41 items and is measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”). The specific dimensions are detailed below, and the complete scales are provided in

Appendix A.

SPOS: We adopted the perceived organizational support scale developed by

Eisenberger et al. (

1986) to measure SPOS, which is widely utilized in organizational support research for employees (including supervisors) in enterprises and possesses high reliability and validity (

Eisenberger et al., 2010,

2014,

2020). The scale comprises 8 items, including, “The organization places significant emphasis on my objectives and values” (Cronbach’s α = 0.76).

Group-inclusive climate: Our study adopts the measurement scale for group-inclusive climate developed by

Chung et al. (

2020), consisting of 10 total items, the first 5 of which are employed to measure employees’ sense of belonging to the team, including questions such as “I am treated as a valued member of my work group.” In contrast, the last 5 items are utilized to measure the extent to which employees perceive that the team is tolerant of their own uniqueness, including, “ I can offer a viewpoint on work-related matters that differs from those of my group members.” (Cronbach’s α = 0.73).

Felt obligation: The scale we used for felt obligation is that developed by

Eisenberger et al. (

2001). The 6-question scale encompasses items such as, “ I feel a personal responsibility to contribute in any way possible to assist my organization in reaching its objectives.” (Cronbach’s α = 0.72).

Career initiative: The scale adopted in our study to measure career initiative was developed by

Van Veldhoven et al. (

2017) and consists of 5 questions, including, “In my work, I keep trying to learn new things.” (Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

CSE: We adopted the CSE scale compiled by

Judge et al. (

2003), consisting of 12 items, of which 6 items are used for positive measurement and 6 for negative measurement. The contents of the scale include, “I am confident I will get the success I deserve in life.”, “Sometimes I feel depressed. (-).” (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

3.3. Data Collection and Sampling

This study utilized a matched survey questionnaire method for data collection, wherein sales department supervisors and their sales staff completed questionnaires to evaluate different indicators. To minimize common method bias, the matched questionnaires were administered in three waves, with an interval of approximately one month between each collection. The first wave (T1) of data collection was conducted from May to June 2024, the second wave (T2) in August 2024, and the third wave (T3) in October 2024.

The enterprises investigated in this study are all located in Mainland China. Given our focus on the sales department, the size and nature of the enterprises were not considered as selection criteria. Initially, we employed convenience sampling, followed by snowball sampling to broaden the sample range. The electronic version of the questionnaire was sent to the sales team leaders, who were instructed to print it, complete it with their team members, and return the paper version to us. To ensure one-to-one correspondence between recipients across T1, T2, and T3 questionnaires, we collected the last four digits of the phone numbers of the team leaders and their employees from the T1 questionnaires.

A total of 50 teams participant completed all 3 waves of surveys, with 49 teams maintaining a supervisor-to-employee ratio of 1:6 and one team maintaining a ratio of 1:5. Overall, 50 supervisor questionnaires were successfully retrieved, achieving an effective retrieval rate of 83.3%. Additionally, 299 employee questionnaires were successfully retrieved, resulting in an effective retrieval rate of 83.1%. The detailed distribution process is described below:

Time 1: The T1 questionnaire comprised two sections: one for supervisors (variable: SPOS) and one for employees (variable: group-inclusive climate). A total of 60 supervisor questionnaires and 360 employee questionnaires were distributed, with each supervisor distributing 6 employee questionnaires. Ultimately, 52 supervisor questionnaires (retrieval rate: 86.7%) and 345 employee questionnaires (retrieval rate: 95.8%) were collected. Among the employee questionnaires, 312 were successfully matched with supervisor questionnaires, while 33 remained unmatched. The unmatched questionnaires were retained at T1 to allow for potential matching in subsequent surveys, as supervisors may complete their questionnaires later.

Time 2: The T2 questionnaire, completed by employees, included the variables “Felt Obligation” and “CSE”. We surveyed sales teams that had returned the T1 questionnaire (including unmatched responses). A total of 345 questionnaires were distributed, of which 310 were valid (effective rate: 89.9%). Among these, 300 questionnaires could be matched with T1 supervisor questionnaires, corresponding to 50 team supervisors. The remaining 10 questionnaires originated from two special cases: one team experienced a reduction in employee count from 6 to 5 due to turnover, while the other team’s supervisor supplemented the T1 questionnaire for a team of 5 employees.

Time 3: The T3 questionnaire, focused on the variable “Career Initiative”, was completed solely by supervisors who evaluated their respective sales teams. Based on T2 data, 52 teams were initially selected, and questionnaires were distributed accordingly. Ultimately, 50 questionnaires were successfully retrieved (retrieval rate: 96.2%). Data from two teams (one with 6 members and another with 5 members) were excluded due to non-response from their supervisors, resulting in the exclusion of data from 11 employees.

3.4. Statistical Methods

First, we provide a descriptive analysis of the demographics of supervisors and employees using frequency distributions and percentages.

Second, given the need to analyze multi-level data in this study, we employed the statistical power estimation method proposed by

Scherbaum and Ferreter (

2009) as well as the Monte Carlo simulation approach suggested by

Arend and Schäfer (

2019) to evaluate the adequacy of the sample size based on the collected data.

Third, to ensure that common method bias did affect the results, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to examine whether the cumulative variance explained by the first unrotated factor exceeds 50% (

Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). Furthermore, we introduced a common method latent factor into the structural equation model to assess potential changes in model fit indices, following the procedure outlined by

Conway and Lance (

2010).

Fourth, we utilized structural equation modeling (SEM) to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the questionnaire. We constructed a five-factor model as the original hypothesized model, based on our research hypotheses, we combined the variables “SPOS” with “group-inclusive climate”, “group-inclusive climate” with “salesperson’s felt obligation”, “group-inclusive climate” with “salesperson’s career initiative”, and “salesperson’s felt obligation” with “salesperson’s career initiative” to develop four alternative four-factor competing models for comparison. Additionally, a two-level model was constructed to evaluate the structural validity of the questionnaire under cross-level conditions. Simultaneously, we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) and the composite reliability (CR) of the questionnaire results to confirm its validity.

Finally, for hypothesis testing, we applied a multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM) approach to analyze the nested data in this study and assess both the direct and indirect effects among the variables. Additionally, we tested the significance of the interaction terms on the outcome variable and visualized the interaction effects using graphical representations. Following the recommendations of

Preacher et al. (

2006), we further applied the Johnson-Newman technique to examine the practical significance of the conditional effects.

We utilized Mplus 8.0 software for data analysis, and the syntax was guided by the user’s guide provided by

Muthén and Muthén (

2017).

5. Discussion

For salespeople, many performance-related incentives provided by enterprises not only fail to offer adequate motivation but also become a significant source of pressure (

Lewin & Sager, 2009). However, research on how to stimulate proactive behavior among sales personnel remains limited, particularly from the perspective of front-line managers (

Zhao et al., 2024). This study addresses this gap by constructing an influence chain from the organizational support perceived by front-line supervisors to the career proactiveness of front-line employees. It explores the sequential impact mechanism involving supervisor perception, organizational environment, employees’ psychological motivation, and their behavioral choices.

Firstly, SPOS can influence the formation of an inclusive climate within the team. The results of this study confirm H1. Prior research has demonstrated that SPOS enhances the perceived support for employees (

Eisenberger et al., 2014;

Pan et al., 2012), fostering a positive social exchange (

Eisenberger et al., 2014). Employees view supervisors as organizational agents (

Shanock & Eisenberger, 2006). When supervisors transmit the support they perceive from the organization, employees equate this support with that of the entire team. Consequently, a mutually supportive and cooperative team atmosphere is established, resulting in an inclusive climate that employees can perceive.

The confirmation of H2 and H3 demonstrates that an inclusive climate contributes to enhancing sales personnel’s felt obligation and career initiative. In conjunction with the validation of H4, when sales personnel perceive an inclusive external environment, positive self-selection (e.g., proactive behavior) reflects their psychological state of feeling obligated to reciprocate the organization, which aligns with the principles of self-determination theory. Consequently, we have identified a mechanism linking SPOS to the proactive behavior of front-line sales personnel, as evidenced by the results validating H5.

Although Hypothesis H5 has been supported, it is essential to differentiate the “group-inclusive climate,” which is central to this study, from other latent variables. This distinction is necessary because other factors may still significantly influence outcomes. Prior research has predominantly focused on LMX (e.g.,

Pan et al., 2012) or leadership style (e.g.,

Cheng et al., 2022), which primarily describe individual managerial behaviors rather than team-level dynamics. By contrast, group-inclusive climate, as a team-level construct, builds upon supervisors’ actions to foster an environment conducive to employee behavior improvement. While some scholars emphasize organizational-level variables such as team cohesion (

Salloum et al., 2022) and team diversity (

Tang et al., 2017), group-inclusive climate specifically highlights employees’ sense of belonging within the team. This sense of belonging serves as a key driver of intrinsic motivation (

Shore et al., 2011), going beyond mere responses to external changes. Furthermore, front-line salespeople, who frequently work outside fixed locations (

Lyngdoh et al., 2023), may have a weaker perception of “team.” In this context, fostering a sense of belonging becomes particularly critical. Consequently, group-inclusive climate provides a more precise framework for understanding the relationship between the team environment and the intrinsic motivation of front-line salespeople.

It is also important to note that the results indicate no significant direct effect of SPOS on employees’ sense of obligation (β = −0.030, p > 0.05) or career initiative (β = −0.033, p > 0.05). This suggests that the path from SPOS to sales personnel’s career initiative is fully mediated. First, given the complexity of chain mediation, potential latent variables may weaken the direct relationship between supervisor perception and employee proactive behaviors, and these influences cannot be entirely ruled out. Second, logically, the high autonomy of front-line sales personnel depends on both the work environment and their intrinsic motivation. Supervisor perception, as an internal attribute of supervisors, does not directly engage in employees’ self-determination process. Therefore, supervisors must enhance the work environment to ultimately influence employee behavior.

A high degree of decision-making autonomy is a critical component of the role attributes of front-line sales personnel (

Boshoff & Allen, 2000). We consider a salesperson’s CSE as an intrinsic factor. The results of H6 verification indicate that CSE significantly moderates the positive impact of a group-inclusive climate. Specifically, when CSE is high, salespersons are more likely to exhibit positive psychological motivation to repay the organization and set more challenging personal goals. Additionally, this study finds that CSE has a significant direct effect on both felt obligation (β = 0.516,

p < 0.001) and career initiative (β = 0.505,

p < 0.001). This underscores the importance of individuals’ basic self-perception in shaping their responses to external environments and guiding self-determined behavior.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

Despite the well-documented positive effects of proactive behavior on organizations, the role of front-line managers—those closest to employees—is often overlooked (

Kou et al., 2022). This study investigates the relationship between front-line managers’ perceptions and their team members’ behavior, elucidating the influence pathway of organizational support. Prior research attributes front-line employees’ perception of organizational support primarily to the organization itself (

Pan et al., 2012), neglecting specific recipients and transmission mechanisms. It is critical to examine how front-line managers’ perceptions shape both their own behavior and that of their team members. These perceptions affect employees’ views of job characteristics (

Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005), fostering emotional commitment and autonomous motivation, which drive proactive behavior (

Ayed et al., 2024). Compared to studies on leadership styles or managerial personality traits, organizational support perceived by front-line managers can be systematically controlled and regulated by upper management, providing practical implications for business operations. By cultivating such an environment (

Ding et al., 2022), front-line managers can enhance their attitudes and behaviors, positively influencing employees (

Op De Beeck et al., 2018). This addresses the first research question.

Based on self-determination theory, we have elucidated the influence mechanism from front-line managers’ perceptions to the behavior of front-line employees. Previous studies provided only a general description of this mechanism (

Zhao et al., 2024) and overlooked critical factors such as external environmental influences and employees’ intrinsic motivation (

Deci et al., 2017). By incorporating group-inclusive climate and employees’ felt obligation, we bridge the self-determination chain between supervisors and employees, thereby addressing the second research question of this study.

Additionally, we place a higher emphasis on the way salespeople perceive the team environment since, compared with employees in other departments, salespeople have flexible personalized contracts regarding the workplace and working hours, which ensure their social participation and performance in the team (

Kalra et al., 2024). It is necessary for us to undertake a more detailed analysis of the sales staff group. After all, the generation of proactive behavior not only depends on an individual’s perception of the external environment but also on their own personality traits (

Zhao et al., 2024). We consider the intrinsic basis of a salesperson’s personality traits, CSE, as a key factor in addressing the third research question of this study. This extends prior research (e.g.,

Meng et al., 2023) on the influence of organizational support on employees’ proactive behaviors. The results demonstrate that the development of career initiatives does not solely depend on environmental changes; the role of CSE is also crucial. Perhaps initiative is not truly universal. Among people with lower CSE, the loss of self-efficacy hinders them from engaging in their work more enthusiastically, even when they are well-off.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The research findings of this study hold significant practical implications for enterprises. Firstly, motivating employee initiative remains a critical challenge for organizations (

Van Veldhoven et al., 2017;

Hirschi, 2014). In this context, we have re-evaluated the importance of front-line managers’ perceptions. Currently, enterprises often overlook the significance of front-line managers. Compared to other managerial levels, front-line managers face greater challenges and pressures (

Huo et al., 2020). However, they receive limited benefits and are less likely to experience emotional or instrumental support from the organization (

Karltun et al., 2023).

Therefore, organizations should implement targeted support measures for front-line managers and sales personnel. First, organizations can empower front-line managers by delegating authority, enabling them to independently design team incentive mechanisms. Front-line managers, being more familiar with market dynamics, can swiftly adjust team incentives and human resource allocation in response to market changes, thereby improving the efficiency of information feedback. Second, enterprises should enhance stress-resilience training for front-line managers and sales personnel to strengthen the overall stress tolerance of the sales team. Third, by establishing relevant awards, organizations can encourage managers to proactively refine team work strategies and develop personalized performance goals for front-line sales personnel. This facilitates the transfer of team support from managers to front-line sales personnel. Fourth, a more flexible evaluation mechanism should be implemented for front-line managers, allowing them to learn from mistakes during the management process and improve their skills. Finally, smaller units can be established within the sales department, providing front-line sales personnel with opportunities to rotate in managing small teams. Through practical experience, they can acquire management skills and foster a competition–cooperation dynamic among various small teams, ultimately enhancing the overall performance of the sales department.

Secondly, the findings of this study offer managers insights into motivating front-line salespeople. Beyond daily performance evaluations and salaries tied to work outcomes, managers should place greater emphasis on the contributions of front-line salespeople to the team, while addressing their work-related and family-related needs, thereby strengthening their sense of belonging within the team. Additionally, flexible work arrangements and idiosyncratic deal mechanisms function as effective tools for enhancing team belongingness, fostering self-identity, and cultivating felt obligation among salespeople. For salespeople who are less constrained by formal rules, recognition of their value by the organization and management is more likely to stimulate their initiative than rigid rules and regulations.

Additionally, it is necessary to screen the personality traits of salespersons as they need to consciously engage in sales work without supervision; thus, their CSE plays a crucial role in determining their sense of duty and initiative in work operations. Consequently, managers must thoroughly screen employees or assist them in establishing higher CSE levels through encouragement and support.